September 8, 2020

Donald Trump's grandiosity was off the leash when Republicans launched their election campaign from the White House last month.

For the pageantry of the final night of the Republican National Convention, he and his wife, Melania, stepped onto the South Portico, beamed satisfied smiles to an adoring sea of predominantly white faces below and then regally navigated two flights of gracious, curved staircase down to a red-carpeted runway.

In the manner of their famous golden escalator descent for his campaign launch at Trump Tower five years ago, they landed among their people as though sent from heaven.

From the podium, the president delivered 70 minutes of self-congratulation and fearmongering — about health care, unemployment, drug prices, Democratic nominee Joe Biden, NATO, China and so on — punctuated by a boasting reference to the public property he'd expropriated for the night.

"We're here, and they're not," Trump gloated — "they" meaning the Democrats.

Fact-checkers judged the performance a Pinocchio's catalogue of distortion, misinformation, half-truths and flat-out lies. NBC's Brian Williams declared it "gas-lighting visible from space."

Trump has turned up the volume on his favourite rhetorical device: the race-baiting dog whistle.

The plain truth is that the U.S. is suffering through the worst pandemic since 1918, the highest unemployment since the 1930s and racial unrest unlike anything since the 1960s. Yet the Republicans have decided not to produce a campaign platform this election, preferring to hear it from Trump as the campaign rolls along.

More precisely, they've accepted that Trump is their platform — like Louis XIV, "L'etat, c'est Donald."

But he's in peril. So bleak is the landscape for his re-election — Biden led national polling averages by six to nine points through August — that Trump briefly floated the idea of postponing the election until some unspecified time after November.

That didn't fly, and so Trump is left with some of his most familiar tactics from 2016. He has said the only way he can lose the election is if it's "rigged," and he has tried to discredit the reasonable pandemic precaution of voting by mail, claiming it's rife with fraud. (Recently, he even suggested to supporters who plan to vote by mail that they try casting a second vote in person, which not only defeats the purpose of voting by mail but is also clearly illegal.)

Of equal note, Trump has turned up the volume on his favourite rhetorical device: the race-baiting dog whistle.

As the de facto head of the "birther" conspiracy about former U.S. president Barack Obama years ago, Trump learned that it doesn't take much to seed doubt about the eligibility of non-whites for the highest office. Trump has encouraged skepticism about the credentials of Biden's running mate, Sen. Kamala Harris, saying he has "heard that she doesn't meet the requirements" for vice-president but that he has "no idea" whether it's true. (Harris's parents are immigrants, but she was born in Oakland, Calif.)

Among other things, Trump has characterized this summer's Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests as violent, anarchic and "Marxist," criticized NBA players for postponing games in support of the demonstrations and retweeted video of a fist-waving Floridian Trump fan caught in the act of shouting "White power!"

Just days ago, he retweeted a 2019 video of a Black man violently shoving a white woman on a Coney Island subway platform. Police said the man was nothing more than a serial transit nuisance with a history of anti-social behaviour with reported no connection to BLM.

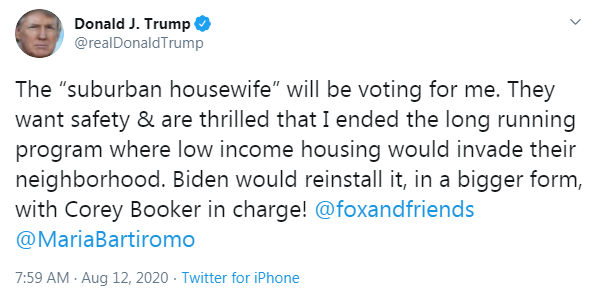

Policy-wise, Trump has often said that during his administration, African Americans have enjoyed the lowest unemployment rate ever. But he also weakened the Fair Housing Act, which was intended to reduce discrimination and break down segregated neighbourhoods. It was such a precisely aimed pitch to suburban women voters — "the 'suburban housewife' will be voting for me," Trump tweeted — that Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson called it "the most nakedly racist appeal to white voters" he'd seen since segregation.

Even as Trump blows hard on the dog whistles, there is evidence they aren't working for him in 2020. Voters are coming to a new understanding of racial justice issues, in part because of the 2016 election — what some academics call "trickle-down tolerance" — and choosing the side opposite from him.

II.

During the 2016 campaign, Trump promised never to use the bully pulpit of the presidency to divide Americans by race, as he claimed Obama had done. But Danielle Moodie, a podcaster and self-described "warrior princess of the resistance," was among those who thought that dividing Americans by race is exactly why Trump was elected.

It would be hard to imagine a person with more anti-Trump matter in her political DNA than Moodie, an under-40, college-educated, Jamaican-American lesbian from Brooklyn who was part of CBC-TV's 2016 election-night panel.

"I literally have nothing left to lose tonight," she said that evening, as she saw Trump elected 45th president of the United States and the Obama era come to an end — not with elegant fanfare but like a light had been switched off.

While the rest of the panel, including myself, politely tried to unscramble how a crude and juvenile reality-TV character could suddenly become leader of the free world, Moodie would have none of it.

"This is literally white supremacy's last stand in America. This is it. This is what this looks like," she said.

WATCH | Danielle Moodie on election night 2016:

Moodie bitterly ticked off a list of warning signs that preceded Trump's elevation to the Oval Office — including birtherism, the Tea Party, the gutting of the Voting Rights Act, voter-identification laws — and rolled them into an incendiary indictment of her country that went on for nearly three minutes (practically an Ice Age in television).

"This was hatred on a level [that] we have not seen since Jim Crow," Moodie said, referring to the period from the post-Civil War era to the mid-1960s, when white leaders engaged in monstrous violence against African Americans through segregation, disenfranchisement and murder.

Soon, a video clip of Moodie's election-night rant was winging its way around the planet. The Buzzfeed headline was "This woman called the U.S. election results 'white supremacy's last stand.'" BET — Black Entertainment Television — said it was "honest commentary." The news site AfricanGlobe broke down her rant into 10 bullet points.

"As a Black, queer woman, I knew exactly what this was going to mean for people like me," Moodie told me a few weeks ago. "I wanted to burst into tears." She let her feelings stream out over the airwaves and unexpectedly became a sensation. "I was taken aback the next day that so many people had reached out. Overnight, I gained something like 10,000 Twitter followers, something crazy."

To Moodie, the next four years seemed to confirm her fears. "Sadly, everything I did say that night on set in Canada in 2016 has come true and worse."

First, Moodie was essentially correct in her sense that white racial insecurity was the key motivator among Trump voters. In the 2018 book Identity Crisis: The 2016 Election Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America, three political scientists concluded from piles of data that the strength of white identity and anti-immigrant sentiment best predicted support for Trump.

As the president seemed to validate white nationalism, racial tensions rose ominously like water behind a dam.

She was also prescient anecdotally: The president got two big thumbs up from former Ku Klux Klan Grand Wizard David Duke in 2017 after his reluctance to condemn a torch-lit white nationalist march through the University of Virginia campus that a day later led to the murder of counter-protester Heather Heyer. Trump defended Confederate Civil War generals and the statues that honoured them in their war to protect slavery. He incited Americans against NFL players when they knelt during the national anthem to protest against police violence.

As the president seemed to validate white nationalism, racial tensions rose ominously like water behind a dam. A mild confrontation between a Black man and a white woman over dog-walking rules in New York's Central Park became national news after the woman called 911 and claimed she was being threatened by a Black man.

Cellphone video and police body cameras brought new and dramatic documentation of police killings of unarmed Black people. Sometimes, the details themselves were shocking enough: Breonna Taylor, a Black woman in Louisville, Ky., was mistakenly killed when police burst into her apartment looking for someone else.

Then, one evening in late May, a white officer in Minneapolis arrested a Black man named George Floyd — apparently, for paying with a phoney $20 US bill — put his knee on his neck and slowly choked the life out of him, unconcerned that cellphone cameras were recording the killing.

The dam broke. Streets across the U.S. filled with protests and demonstrations — some violent — that lasted weeks.

The force of the backlash demanded a response, and it arrived surprisingly quickly.

Confederate statues came down in the South — some at the hands of protesters, others by order of city leaders in Richmond, Va., Charleston, S.C., and elsewhere. Mississippi, of all places, removed the Confederate symbol from its state flag. NASCAR, among the most-potent institutions of southern identity and pride, forbade representations of the Confederate battle flag at its stock car races.

As the Floyd protests spread beyond the U.S. — to Canada, France, Germany, Japan, the U.K. and other countries — it seemed there was a global awakening. No less than John Lewis, the late Congressman and legendary warrior of the civil rights era who died in July, thought it a moment unparalleled in the history of the Black struggle for freedom.

Moodie was channeling Lewis when we spoke.

"During the civil rights movement, it was Black people in the streets for Black people. White people weren't even on the sidelines. And now, you look out at these demonstrations — in some of the most lily-white, rural places, they have stakes in the ground, literally, that say 'Black Lives Matter.'"

The writer Ta-Nehisi Coates went through a similar evolution. In the October 2017 issue of The Atlantic, he had written that Trump's success was "at best in spite of his racism and possibly because of it. Trump moved racism from the euphemistic and plausibly deniable to the overt and freely claimed."

But after the George Floyd backlash, Coates told The Ezra Klein Show podcast in June, "I see hope, and I see progress." Coates recounted a conversation with his father, a former Black Panther, about the George Floyd outrage.

"The idea that that would resonate with white folks in Des Moines, Iowa, that it would resonate in Salt Lake City, that it would resonate in Berlin, that it would resonate in London ― it was unfathomable to him," Coates said.

It seemed as though some of the "hope and change" promised in the Obama era had unexpectedly arrived in the Trump era — as though the culture had suddenly and dramatically changed, like the weather sometimes does.

III.

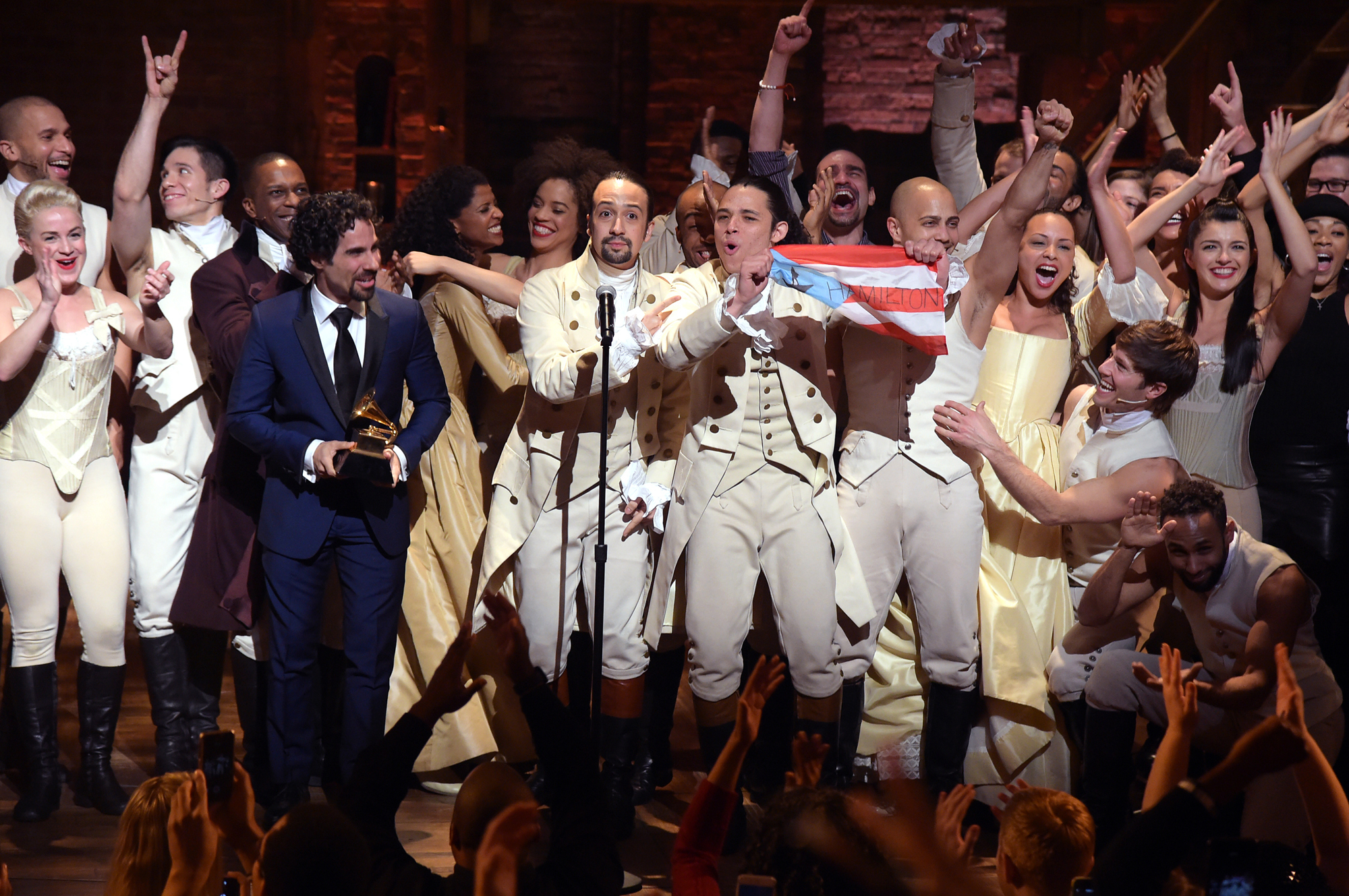

Nothing captured the unrequited hope of the Obama era so dazzlingly as the Broadway musical that opened in New York near the end of his presidency.

Created by Lin-Manuel Miranda, Hamilton salutes the founding myths of the United States. It features a hip-hop soundtrack performed by African Americans and Hispanics in the roles of the founders — George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton. The musical tries to be unselfconsciously post-racial, but it can't be that and also be true. So, it tells a customary rendition of America's founding, which is to say, a rendition that overlooks slavery.

This year, the Disney Plus streaming channel offered a film version of Hamilton. The show remained the same — catchy, clever and elegant — but the culture beneath it had shifted. Miranda had to explain to a 2020 audience why he'd ignored slavery. It didn't fit the uplifting thrust of the story, was more or less his answer, but he accepted the criticism. "Did my best. It's all fair game," he tweeted.

Hamilton the play and Hamilton the movie "were given to us in two different worlds," tweeted African American writer and podcaster Tracy Clayton. She was still a fan of the show but thought that much had changed since its debut in 2015.

Two different worlds, indeed. In a broad sense, the world of Hamilton has been replaced in the culture by a world more attuned to something like the 1619 Project.

Originally a special issue of The New York Times Magazine published last year to mark the 400th anniversary of the first slave ship's arrival off the coast of Virginia, the project's bold aim was to establish 1619 as the true founding date of the nation. It made the deliberately provocative claim that "it is finally time to tell our story truthfully."

The magazine piece — an assemblage of written and photographic essays and poems — was a sensation. People lined the sidewalks outside the Times headquarters for free copies. It has since won a Pulitzer Prize and expanded into an ongoing project and a podcast series.

Conceived by staff writer Nikole Hannah-Jones, the 1619 Project posits that the U.S. was literally built on slave labour and identifies the many ways slavery scars the country even now. It reframes the story of the U.S. and puts "the history you did not learn in school" at the centre, even offering "curriculum, guides and activities for students."

Some historians dwelled on its imperfections — for instance, its un-Hamilton-like claim that protecting slavery was a primary motivation behind the American Revolution — while others countered that the strengths of the 1619 Project far outweigh any weaknesses and that the conversation it provoked was vital and necessary.

The resultant controversy was immediate, intense and political. Conservatives accused the Times of liberal overreach. The commentator Dinesh D'Souza said the 1619 Project was "a political hit job to undermine Trump and his base." (The presumed association of the 1619 Project with anti-Trumpism seems revealing.)

Arkansas Republican Sen. Tom Cotton went so far as to draw up a Senate bill to cut funds to public schools if they dare teach the 1619 Project. (The bill is not expected to pass.)

As with many arguments about history, the dispute over the 1619 Project was less about facts than about interpretation and emphasis. The real question was whether the U.S. had the maturity to accept that its history had been written mostly by the dominant race — white men — and was therefore incomplete at best and flat-out wrong at worst.

As Jill Lepore writes in her 2018 book, These Truths: A History of the United States, "to write something down doesn't make it true, but the history of truth is lashed to the history of writing like a mast to a sail." Slaves were not only denied permission to write their own story; they were denied the ability to write at all.

African Americans have really only begun to make up for centuries of whites writing them out of U.S. history. What was once difficult for Blacks to write might be almost as difficult for some whites to read.

Isabel Wilkerson's book Caste has sat near the top of bestseller lists this summer. In it, Americans can read about Hitler's Nazis studying Jim Crow laws as a how-to guide for the persecution of Jews; the election day massacre of Blacks in Florida in 1920; the casual humiliation and even murder of African American children in the mid-20th century, as well as other horrifying facts of the American story.

The retelling of U.S. history through African American eyes is one side of the current cultural re-evaluation. But the bestseller lists in the Trump era also have books such as Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism and Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be An Antiracist.

Arguably, investigating the truth of America's history and writing it down is more urgent in these times. Among the most distinctive and dangerous features of the Trump era is a disregard among some for facts and evidence and the consequent surrender to the human temptation to believe what's most convenient.

No one understands that foible, or uses it more effectively, than Trump. Essential to his exploitation of racial tension is his understanding that people will believe what they want to believe about others so that they can believe what they want to believe about themselves.

IV.

At the end of his book Team of Vipers, a mixed review of the Trump White House, Cliff Sims, an energetic Trump supporter and former aide who left that job in 2018, tells a story about the president and the NFL protests started by quarterback Colin Kaepernick in the summer of 2016.

Trump had deliberately provoked a backlash against the protests when he told a crowd in September 2017, "Wouldn't you love to see one of those NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, 'Get that son of a bitch off the field right now. Out. He's fired. He's fired!'"

Sims recounts how, in a private conversation months later, the president congratulated himself for anticipating the backlash against the overwhelmingly Black players who knelt during the singing of the national anthem.

Quoting Trump, Sims wrote, "'I knew it from the moment I said it — everyone's going to agree with me on this, most everyone. It's about our country. People are sick of their country being disrespected.' [Trump] then switched gears, and with a wily grin began considering how this would play out during his re-election campaign.

"'The Democrats — you watch — they're going to nominate a kneeler,' he crowed. 'They're going to nominate a kneeler, and I'm going to beat the hell out of them.'"

Then, wrote Sims, Trump "tied a bow on his thought, saying, '2020 will be fun, that I can tell you — a lot of fun. The kneelers! Just watch!'"

Sims recounted the story admiringly, apparently unable to see that someone else might consider Trump's calculation as pure race-baiting.

Last year, Sims ran into someone who forced him to look more closely at the president's tactics. In a Q&A, the New Yorker's Isaac Chotiner asked Sims whether Trump says racist things. What ensued was a long, tortured exchange that eventually got to the racist birtherism hoax and ended this way:

Chotiner: So what do you think about [birtherism]?

Sims: I don't know. I have never talked to [Trump] about it. I don't know.

Chotiner: You have written a book that is going to be a bestseller. You say the president is not a racist. You say you are a communications strategist. You're selling yourself as a smart guy, and you're telling me you don't know what birtherism was about. So, I'm asking you what birtherism is about.

Sims: I mean, I know what birtherism was about in terms of what the ... I guess I am confused at your question. I'm not sure what you are trying to get at here.

Chotiner: You keep saying you know what birtherism is about, but you're not telling me what you think birtherism is about. You have written in your book that Trump does not have a racist bone in his body.

Sims: So, I think that's, like, a great example of a time when he does not step up to the plate and take on these race issues in an appropriate way, a helpful way for the country. No doubt that that was terrible. I don't know what else you want me to say about it.

Chotiner: We have been talking for five minutes about this, and it took you that long to say that.

Sims does not represent every Trump supporter. But he offers an example of what a smart, young (36) supporter from Alabama, who is also an evangelical Christian who says his faith is an important part of his life, seems to tell himself when confronted with what, almost by definition, is race-baiting.

At best, Sims just doesn't think about it; at worst, he excuses it as a legitimate tactic in the warfare of election campaigning — the price one pays to win. As though birtherism and NFL race-baiting are issues about which people can disagree just as they disagree about tax policy and health insurance.

In the final weeks of the 2016 campaign, Trump conceded that there was nothing to the birtherism hoax — but by then he had wrung out of it everything he needed to launch his political career.

V.

When Trump officially accepted the party's nomination at the Republican National Convention in August, he told his audience, "I say very modestly I have done more for the African American community than any president since Abraham Lincoln, our first Republican president."

At other times, he has said, even less modestly, that he's done more than Lincoln.

Both claims are ridiculous. Most historians would say Lyndon Johnson — who got civil rights and voting legislation passed — did far more for African Americans than anyone since Lincoln. Many would say Ulysses S. Grant, who created the Justice Department to suppress the Ku Klux Klan and enforce federal civil rights laws, and Harry Truman, who desegregated the military, did more than Trump.

The current president makes the claim partly to satisfy those supporters who need to believe he's not who he appears to be on race issues, and partly to try to undercut African American support for Democrats; he'd benefit if they didn't vote at all on election day.

Indeed, one reason Hillary Clinton lost to Trump in 2016 is that many Black voters who'd come out for Obama in the previous two elections stayed home. That hasn't been the case since.

Black voter turnout helped Democrats win a 2017 Senate election in Alabama, of all places. They were also an important part of the Democrats' 2018 midterm landslide. Black voters helped resurrect Joe Biden's faltering presidential bid and made him the Democratic nominee in a dramatic turn earlier this year. To some degree, it is in response to those things that a Black woman is at the top of the ticket with Biden in November.

It was on Aug. 12, the day after Biden announced Kamala Harris as his running mate, that Trump tweeted his comments about dismantling part of the Fair Housing Act. In it, he said suburbanites "want safety and are thrilled that I ended the long running program where low income housing would invade their neighborhood. Biden would reinstall it, in a bigger form, with Corey Booker in charge!" (Booker's first name is spelled Cory, not Corey.)

The dog-whistling was loud and unmistakable. Biden hasn't named Booker, the junior senator from New Jersey, to any possible future post. He might be in a Biden administration; he might not. But he is Black and could have power, and to a certain kind of voter, that alone seems like a threat. That was likely Trump's hope.

Not only that, but the language of the tweet ("suburban housewife") seemed borrowed from an earlier era. Trump's understanding of the demographic reality of suburbia was outdated, too. It's much more diverse than it was.

In the aftermath of George Floyd's killing, public support for BLM increased — to a clear majority in some polls — but in the last few weeks, as the violence of protests in Portland, Ore., and Kenosha, Wis., have drawn national attention, it has dropped back to where it was, at just below 50 per cent.

But that has had no real effect on the presidential race. Biden still leads Trump nationally, and he leads in all the battleground states, according to the poll averages on Fivethirtyeight.com.

That will have to change — and it could — to improve Trump's chances in November. But his conviction that the best way to get there is by appealing to white racial insecurity seems unlikely to change — ever.