May 16, 2018

Mary Farrar was raised Anglican, and growing up, she got used to the idea that when someone dies, they were to be embalmed, placed in a casket and lowered into a brick or concrete grave vault.

But when it came time for the 77-year-old to think about burying her husband, Edward, the old ways no longer felt natural.

It was partly due to her disenchantment with the church, but mostly out of respect for Edward’s world view. Mary and Edward raised their family in Inverary, a bucolic town outside of Kingston, Ont. Mary was an elementary school teacher and Edward was a geophysics professor at Queen's University, and every seven years, the couple took a one-year sabbatical so the family could backpack around the globe.

Together, they experienced the wonders of nearly every country on Earth. "I can’t think of anyone else that I could have married who would have taken me to eat oysters out of the ocean or baked potatoes in a volcano in Hawaii," Mary said recently.

In 2010, with the kids out of the house, the Farrars moved to downtown Kingston, where they discovered a large, vulnerable population of turtles and became involved in the protection of the city's inner harbour.

It was around this time that Edward had his first setback. While the couple was travelling in Vietnam, he experienced a profound mental block trying to calculate a simple currency conversion. It turned out he had a stroke. Edward was eventually diagnosed with vascular dementia and Alzheimer's. Although Edward often forgot key details and lost his train of thought mid-sentence, the couple adjusted to his growing memory loss and even managed to continue travelling.

By 2016, Edward had become increasingly agitated. This is a common side-effect of dementia, but it presaged a darker turn of mind. That March, Edward became convinced that Mary wanted to kill him — and one day, he tried to strangle her. Mary was standing just outside the kitchen when Edward attacked her. She instinctively dropped to the ground, which put him off balance long enough for her to wriggle free. It saved her life.

Mary scrambled out of the house. The police were called and Edward was eventually taken to hospital, where he was put in care and given antipsychotic drugs. While in hospital, Edward almost died of pneumonia, and later was nearly overdosed. Now in the psychiatric ward at Kingston General Hospital, Edward can no longer speak, doesn't recognize his family and can’t walk or bathe without the aid of nurses.

While painful, the circumstances gave Mary an opportunity to consider the most suitable resting place for Edward when the time comes. She reflected on their life together — their epic hikes, his readiness to pitch a tent almost anywhere, their love for the turtles.

She had heard from a neighbour about the concept of a green burial. No embalming fluid. No fancy casket. The body would go directly into the ground. It made sense.

Mary purchased a burial plot for Edward at Cobourg Union Cemetery, a two-hour drive west and one of the few places in Canada to offer such a service. She also bought a cotton shroud in which his body will be wrapped.

"Given how much he was an environmentalist and how much he cared about nature, it seemed appropriate," said Mary. "And given how much of a penny-pincher he was, and how much he would have objected to being taken to the cleaners by funeral homes, it seemed like the best alternative."

Farrar is part of a small but growing movement of people who for ecological, spiritual or financial reasons are seeking body disposal methods that are more environmentally sound. In so doing, they are fulfilling the idea that the human body was meant to return to nature — to be recycled, if you will.

Greater awareness of the environmental costs of conventional funerals is leading some scientists to explore ways of recycling our bodies beyond green burials. The idea may be distasteful to some, but in light of an increasingly crowded, contaminated planet, others see it as a responsible, practical and fitting final act.

But convincing more people to abandon longstanding funeral customs and go green requires changing our minds about what it means to die.

II.

Death is a subject few of us can approach objectively. Many of us prefer to avoid it altogether. The inevitability of our own demise is tremendously depressing and not something we wish to dwell on while trying to make a living, raise a family or seek escape in the latest Netflix series.

There is also our general disgust with dead bodies. We have many euphemisms for dying that acknowledge our role in the ecological cycle ("pushing up daisies," becoming "worm food"), but for most of us, human decay is the stuff of horror films and too repulsive to contemplate.

This is why when death strikes, many of us feel most comfortable leaving it to professionals to help us navigate the aftermath, from handling the body to preparing it for burial or cremation.

"A lot of it has to do with customs and traditions. Family members are just used to doing what has been done before," said Roger Girouard, president of the Canadian College of Funeral Service in Winnipeg. "It's hard for them to break away from tradition."

The funeral business in North America is a multibillion-dollar industry, and one of its signature offerings is embalming, a process designed to slow the decomposition of the body and keep it clean for public viewing. Although the results can look surreal, embalming can give mourners closure by allowing them a last look at their loved one.

Girouard said there's a "psychological benefit" to embalming. "It allows family members to say goodbye," and can be particularly comforting "if there's guilt, if there's complicated grief."

"All of that formaldehyde going into the drinking water is just disgusting."

Western religious and cultural practices have led consumers to cling to the idea of preservation as a sign of respect for the deceased, "even as we may recognize intellectually that this isn't rational," said Cassandra Yonder, a "community death care educator" who provides guidance on home funerals in Cape Breton, N.S.

The fact that the "sales pitch" for many funeral homes is preserving a corpse in an elaborate casket doesn't make sense to Yonder. "Some burial practices are clearly based on, 'If you buy this particular type of container, your remains will last longer.' Which is crazy, because you're just turning into a gross sludge inside them."

Detractors say this longstanding practice has a number of unintended ecological costs. A 2011 study by researchers at Trent University in Peterborough, Ont., said among the known impacts humans have had on the environment, "one rarely addressed source of contamination that poses risks is the disposal of corpses."

Embalming fluid typically contains a mixture of formaldehyde, methanol, ethanol and other solvents. Formaldehyde is a known carcinogen, and according to the Funeral Consumers Alliance, more than 20 million litres of embalming fluid are used every year in the U.S. alone. Meanwhile, most standard caskets contain metal, synthetic fabrics and varnish — materials that won't biodegrade — and they're typically contained in a concrete grave liner.

Cremation has become a more popular option in the West — the Cremation Association of North America reports that in 2016, the cremation rate surpassed 50 per cent in the U.S. and 70 per cent in Canada. But cremation is also problematic from an environmental standpoint.

It requires intense heat (approximately 800 C), and a typical cremation uses as much natural gas as heating an average home for a week, according to the Cremation Association of North America. (Green burial activists insist cremation has an even larger carbon footprint.) That doesn't address the off-gases of burning mercury tooth fillings or metal implants, or what happens when you scatter bone ash in fields or bodies of water.

One greener option that has been gaining attention is alkaline hydrolysis — sometimes called flameless cremation — which breaks a corpse down using a liquid solution of water and potassium hydroxide (or lye), leaving only bones. It uses a fraction of the energy needed for conventional cremation but requires a lot of water and has run into some regulatory issues in the U.S. and Canada.

Given the unintended consequences of conventional burial and cremation, Farrar believes green burial is "a way to truly heal the land."

"All of that formaldehyde going into the drinking water is just disgusting," she said.

Farrar bought a plot for her husband — as well as for herself — at Cobourg Union Cemetery, which has offered green burials since October 2009. The area sits in a quiet meadow overlooking a river (and a nine-hole golf course). According to Michel Cabardos, the cemetery's superintendent, there are 48 people buried there.

By law, a grave must be at least two feet deep. "Some people would like to be buried more shallow, to be in the active layer of soil to compost quicker, but we must go at least two feet," Cabardos said. Like other green sites, the section at Cobourg Union does not have tombstones, although it will allow modest grave markers, such as a smaller rock with a name sandblasted on it. The ultimate aim is for the vegetation to grow over the burial sites.

This concept of returning to the soil greatly appealed to Bert Gahn, a man with terminal cancer in Niagara Falls, Ont. When he heard that a local cemetery, Fairview, was going to offer it in the fall of 2017, he told his family he had to be buried there — he was even willing to take the unusual step of putting his body on ice at a funeral home for several months to make it possible. Hearing about Gahn's interest, Fairview expedited the development of its new green site, Willow's Rest, making it possible for Gahn to be interred there a full four months before it officially opened.

Gahn's sister Barbara and brother Brian were able to convey this news to him two days before he died. "He was sitting in his hospital bed," Barbara Gahn said. "He smiled and gave a thumbs-up and said, 'So, I will be No. 1?' We said, 'You will be No. 1.'"

According to Stephen Olson, a board member of the Green Burial Society of Canada, only a handful of cemeteries across Canada provide green burial sections. There is only one dedicated green burial cemetery in Canada — a tract roughly the size of a hectare on Denman Island, just off the east coast of Vancouver Island, that opened in October 2015.

Olson, a nearly 40-year veteran of the funeral industry who oversees a green site at Royal Oak Burial Park in Victoria, said Canada is "just at the thin edge of the wedge in terms of more people wanting it, asking for it."

The global leader in this respect is Great Britain. Concerned that cremations were accounting for more than 90 per cent of body disposals, activists in Britain started promoting green burials. Rosie Inman-Cook, manager of the Natural Death Centre in Winchester, England, estimates there are now more than 300 green burial sites across Great Britain.

She said the interest in green burials is rooted in concern for the environment but also a "lack of conventional faith" and a "dislike for morbid, gloomy rows of headstones." It is estimated that about eight per cent of the more than 150,000 burials that take place in the U.K. each year are now green burials.

Because it eschews many of the materials of a more conventional funeral, a green burial is typically cheaper. Olson said the biggest challenge in Canada is making people aware that it's even an option. He said that when he describes the philosophy and process to potential customers, the benefits become obvious. "When you explain it to [people], it's almost literal. You can see the light go on. It's like, 'Wow, this makes sense. It appeals to me. It appeals to something very profound in my value system.'"

A couple of years ago, Olson received an important bit of validation from an Alberta woman who had read about his work in Victoria and asked if there were similar sites in Edmonton. "She said, 'I'm a very devout Catholic,' and she said, 'When I read [about green burials], this just resonated with me so much. This is the way they buried Christ.'"

III.

The notion of recycling bodies might seem new, but many of the practices are actually centuries old.

The funeral industry as we know it has only existed for about 150 years, and many of the processes associated with it — particularly embalming — arose during the U.S. Civil War.

A number of non-Christian religions and cultures have burial methods that seek to hasten, rather than hinder, natural decomposition — they just haven't marketed their beliefs as environmentally friendly, said Jonathan Jong, a researcher at Coventry University in England who studies the reasons behind religious belief.

"There are no actual official theologies of green burials from most religious traditions," said Jong. "But some religious traditions are more or less easy to greenify."

In Judaism, for example, the body is meant to be buried within 24 hours of death, without embalming, in an unadorned wooden casket. In Islam, the body is simply placed in a shroud.

Zoroastrianism, the world's oldest monotheistic religion, which originated in modern-day Iran and India, promotes a "sky burial." Bodies of the faithful are ideally placed in circular, open-air structures called Towers of Silence, where vultures or other scavengers literally pick them apart.

Funeral practices in North America have largely been based on the Christian tradition of preservation, but some cultures are rediscovering more ecologically friendly methods.

When someone dies on Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory near Kingston, most residents opt for a conventional funeral. But the community got a glimpse of a more traditional method after the death of Patrick Maracle in 2011. Because the 37-year-old Maracle was a member of the Tyendinaga Haudenosaunee Longhouse — a body that is trying to revive pre-colonial spiritual, social and political traditions — his funeral was one of the first opportunities to demonstrate the old ways.

Pauline Maracle, a cultural programming director on Tyendinaga and Patrick's sister, said once a Mohawk dies, the body is meant to be kept in the home for 10 days. They preserve the corpse by putting it in a bath infused with cedar and placing sacred medicine in every hole of the body. "Our No. 1 most important responsibility to creation is to protect Mother Earth, so since the beginning, we've never used embalming fluids or anything," said Maracle.

"Can we reimagine our traditions to be more green or do we have to revolutionize them?"

Once it is ready to be buried, the corpse may be wrapped in an animal hide, such as that of a deer or a caribou, or it may be placed in a cedar casket carved with images symbolizing the life of the deceased — "our story in pictures," said Maracle. Then, the body is placed in the ground, so the person's physical remains are returned to Mother Earth while their soul travels to the spirit world.

"We buried our people this way many years before the Europeans even came," said Maracle. But as a result of the suppression of many traditional Indigenous practices through systems such as residential schools or the Sixties Scoop adoption program, many in Maracle's own community were unaware of how Mohawk people are meant to bury their dead, she said.

Maracle said that when her brother died, more than 1,500 people came out to witness the burial ritual. At present, the traditional burial site at Tyendinaga has fewer than 10 bodies, but Maracle said that after witnessing her brother's interment, more community members have expressed a wish to be buried in the same fashion.

"It was an eye-opener for our own people," Maracle said.

Jason Kelly, a professor at Queen's University's School of Religion, says an issue facing all the major world faiths "is can we reimagine our traditions to be more green or do we have to revolutionize them?"

"Indigenous traditions don't have that issue, because they're already green."

IV.

The human body is about 65 per cent water, 20 per cent protein, 10 per cent fat, five per cent mineral and one per cent carbohydrates, and if placed directly into the ground, it will take years to decompose. (And the bones will remain much, much longer.)

But interest in the idea of recycling our bodies has led some enterprising scientists to look at ways to accelerate the decomposition process.

Katrina Spade, a designer living in Seattle, has spent the past few years developing a process that sounds a lot like human composting. The basic concept is quite simple: Lay a corpse on a bed of wood chips, cover it with more wood chips and aerate it for 30 days. After a month, nature will have reduced the muscle, fat, sinew and bone to something resembling topsoil, leaving only synthetic materials (such as screws or artificial hips) as residue.

"If you take a body that's high in nitrogen and cover it in rich material like wood chips, you've created the right environment for microbes and bacteria to break the body down quite quickly," said Spade.

Spade, who grew up on a "dead-end dirt road" in New Hampshire, said her research was inspired by a farming practice of composting dead livestock, rather than incinerating or burying it — something she said has happened for at least half a century.

"That was a bolt of lightning, really," said Spade. "I mean, geez, if we can recycle an animal back to the land in a way that is expedient and sustainable, then we can certainly do that with humans as well."

While Spade is confident about the science, the process has yet to be done on a human corpse. Her company, Recompose, is currently working with Washington State University to meet government regulations on body disposal. Spade hopes the process will be available in a couple of years.

The environmental impulse has led to more fanciful ideas. A couple of years ago, a pair of Japanese fashion designers came up with a mushroom burial suit, a full-body garment containing mushroom spores that grow after burial and help digest the body as it decomposes.

While intriguing, these earth-based solutions don't take into account one of the realities of modern life — that most people live in cities, which are increasingly strapped for space. Kartik Chandran is working on a process of accelerated decomposition, but he's doing it in the teeming metropolis of New York. Chandran is an environmental engineer and member of DeathLab, a multi-disciplinary initiative based at Columbia University that is researching and designing solutions for how to accommodate the dead in cities.

The chemical process being developed at DeathLab would harness reusable compounds from corpses. Chandran referred to it as a "recovery of resources."

"Instead of taking something and burying it or landfilling it, [we] try and extract something useful from it," he said.

The human body is predominantly made of carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and other elements. Using specific microorganisms and a process called anaerobic fermentation, the researchers in Chandran's lab can convert organic carbon to energy in the form of gaseous methane, hydrogen or electricity.

In the process, they also separate out nitrogen and phosphorus, which can be used as nutrients for vegetation. Some of these microorganisms can wring out even simpler products, such as acetic acid. Once the process is complete, the residual materials include some organic and inorganic compounds that are hard to degrade biologically.

Chandran's lab hasn't tested this on a corpse. In lieu of human flesh, they are currently using pork chops. But Chandran is confident these microorganisms can eventually handle a larger specimen.

"I don't think there's any kind of limitation" to what microorganisms can achieve, Chandran said. "This is what they do. They've been doing this forever. And it's only now that we're realizing their potential."

V.

Science clearly has ways — old and new — to reduce us to reusable matter. But getting more people to entertain such methods requires us, collectively, to become less squeamish about how we leave this world.

"I don’t understand this total terror of death," said Farrar. "But it's everywhere."

One organization that has given this a lot of consideration is the Order of the Good Death, which is made up of North American funeral industry workers, consultants, academics, artists and activists. A proponent of a movement called "death positivity," the order aims to broaden "the exploration of what death means," said member Jeff Jorgenson, a funeral home director in Seattle.

One of the order's central tenets is that "by hiding death and dying behind closed doors, we do more harm than good to our society." The group advocates treating the subject openly, honestly and with purpose. And while the job titles of some members sound laughably ghoulish — the roster includes a "morbid cake maker" — the aim is to make death less scary.

For the Order of the Good Death, that means "embracing decay" and the idea that "death should be handled in a way that does not do great harm to the environment."

Most members either provide or advocate ecologically sensitive burials. Jorgensen's business, for example, offers green burial, biodegradable urns and non-formaldehyde-based embalming options, in addition to more conventional funeral services. Yet despite his green advocacy, Jorgenson knows first-hand that saving the planet is not top of mind when a loved one dies.

He was with his mother in hospital in 2013 when she lost her life to lung cancer. Although Jorgenson had at one point considered a green burial, the family decided on cremation because a natural burial wasn't part of their tradition.

"I'm sitting at my mom's deathbed and just watched her take her last breath. And I couldn't bury her," he said. "It really didn't matter to me in that moment what the carbon footprint was. I didn't really care what that was. I needed to do what gives me healing. And I think that's where most people are."

The immediate mourning period is typically so rife with emotion that it crowds out bigger-picture considerations. In this respect, Mary Farrar is in a unique situation. Her husband's ordeal gave her time to contemplate the appropriate way to bury him.

"Edward always had a really strong sense that he wanted to give more than he took, and in a way, giving your body back to the earth is kind of the last gift," she said.

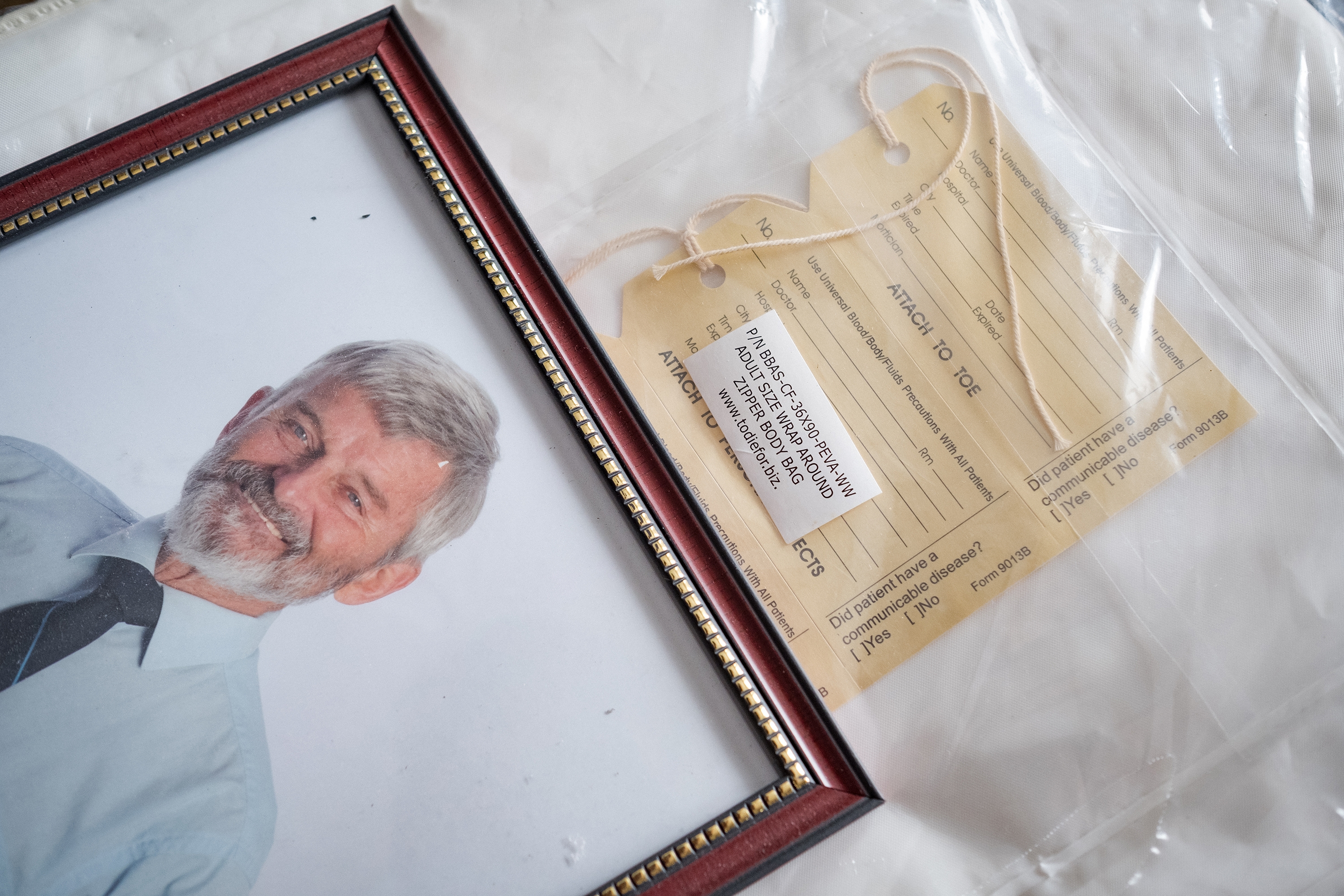

Mary is decidedly unsentimental about what will happen when he dies. They will donate his organs and corneas. They will then place his corpse in a body bag and drive it down the Trans-Canada Highway to the cemetery.

There, he will be wrapped in a cotton shroud. In front of a small gathering of Edward's family and closest friends, workers will lower his body into the ground and pour the soil over him.

The way Mary imagines it, the process will be quick and austere. In its simplicity, it will honour Mother Earth. And in its lack of ceremony, it will appease her husband: "Edward always hated funerals."