March 13, 2018

This story is part of our series Water at Risk, which looks at Cape Town's drought and some potential risks to the water supply facing parts of Canada and the Middle East. Read more stories in the series.

What does it say about a society when having greasy hair is considered an act of virtue? Or opting for ice cubes in your Chardonnay instead of keeping an ice bucket at your table is a gesture of conservation?

In a city like Cape Town, one of the most beautiful in the world but also one of the most unequal and one that’s facing down a profound water shortage, it means sacrifice is almost always in the eye of the beholder.

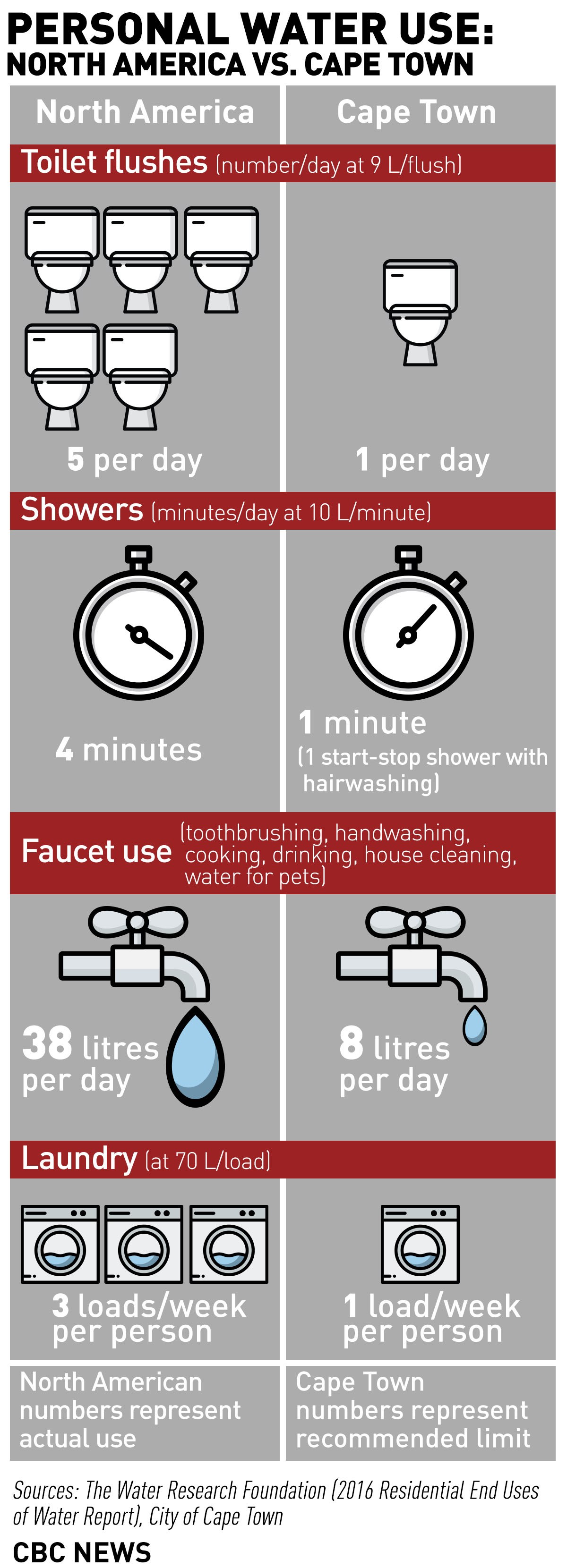

Three years of unprecedented drought have left the South African city’s rain-fed reservoirs below 25 per cent capacity. All residents, whether they live in a suburb or a shantytown, have been told to limit their consumption to less than 50 litres per person per day, or risk hastening the arrival of Day Zero, when levels become so low authorities opt to shut down the system and ration water to the city's four million residents.

Well-to-do Capetonians engaged in the conservation effort are fond of saying the water crisis has done much to pull the city together because everyone is in the same boat, albeit a grounded one.

“It’s a leveller,” says Mariehette Davel. “We’re all the same now. If there’s no water, nobody’s got water.”

Davel owns and runs a small eco-friendly hotel in the leafy suburb of Rondebosch, not far from Cape Town’s botanical gardens.

She uses captured rainwater to wash floors, do laundry, water the plants and fill the swimming pool. Guests are asked to flush their toilets using the water left for them in buckets in their rooms.

A single flush can use up to five days’ worth of drinking water and signs in bathrooms all over Cape Town urge people: “If it's yellow, let it mellow. If it's brown, flush it down.”

People tell funny tales of having to reverse months of parenting by teaching their children NOT to flush and NOT to use soap and water to wash their hands. It’s hand sanitizer or nothing.

And confused visitors to the city can sometimes be spotted emerging from restaurant bathrooms with their hands soaped up because the owners have gone to the effort of actually removing the taps.

“There are still people that shower every day,” Davel says with genuine horror. “I think it’s crazy!"

“I shower once a week when I wash my hair. For the rest I wash in a bucket every morning like most of South Africans, like most of Africa does. It’s a leveller,” she says with a smile.

But out back, workers are putting the final touches on the borehole she’s just had dug on her property at considerable expense, gambling that she’d find groundwater.

And she did.

It will essentially take her off the municipal system and give her peace of mind in terms of keeping her business going if the city doesn’t manage to stave off Day Zero.

The day was first forecast to arrive in April, but has since been pushed back several times and now sits in August. Authorities believe they can avoid it this year if drastic cuts remain in place and the rains arrive.

But Davel says she doesn't trust city officials or her fellow Capetonians to solve the problem.

“I have 34 rooms,” she says. “I have 22 staff that work for me and they’re all breadwinners. So I cannot close my doors. And if I don’t have water, I can’t have a guest.

“It’s as simple as that.”

But nothing is simple about Cape Town’s water crisis.

There are an estimated 30,000 boreholes on private properties around the city, for example. Most are registered, but there’s no real way to monitor consumption or what the water is being used for.

If anything, the water crisis has exposed how entrenched racial, social and economic schisms remain in South Africa more than two decades after the end of apartheid.

II. Pointing the finger

“They victimize us because our houses are bigger,” a large man says as he waits in line with dozens of others to collect fresh water at the Newlands Spring, not far from Davel’s boutique hotel.

It’s become a mecca for residents from across the city since the start of the water crisis, one of an estimated 30 springs that run beneath Table Mountain.

The suburb’s quiet affluence has been shattered by long lines of people armed with water bottles and the sound of trolleys being dragged up and down the street.

Young men will haul your water for tips. The city’s new Uber drivers, they call themselves.

The water here is clear, drinkable and, for now, free. It’s limited to 25 litres per person. If you want more, however, you can simply go stand in line again.

The angry man, who declines to give his name, makes it clear his wrath is not reserved just for the city authorities who have raised his taxes and reduced his water pressure — two ways to control consumption in neighbourhoods where the grass is still green and swimming pools full.

He also has his eye on Cape Town’s townships and informal settlements, accusing those residents of wasting water.

“I can take you to [an informal settlement] and ‘Whoosh!’” he says. “Strong water coming out of their taps. And I’m the one that’s paying their water!”

Informal settlements are the shantytowns on the edges of the slightly more formal but still underdeveloped townships.

Water provided by the city is available for free through communal pumps shared by dozens of families.

The townships and settlements together account for just four per cent of the city’s water usage.

But that doesn’t seem to matter to the man working himself up into a rage.

“Their water is not rationed. The water is staying there. Because if [the authorities] take a chance to reduce pressure there [the people in the townships] start burning tires.”

III. Cracking down

The wind blows hard across the Cape Flats to the south and east of Table Mountain, home to most of the city’s townships and informal settlements.

In the 1950s, the Flats were dubbed "apartheid’s dumping grounds." Non-whites were forced to live there after being pushed out of the city’s developed areas in the centre of town.

Sipo, 31, runs a car-washing business near the township of Mfuleni, close to the seaside. He describes himself as an entrepreneur, but declines to give his family name.

Car washing has become a risky business during the water crisis, especially makeshift ones like Sipo’s run on the side of the road.

Tourists arriving at car rental agencies are greeted with apologetic signs explaining that the cars might be a little dirtier than normal.

And Cape Town’s municipal police are handing out fines and closing down anyone suspected of using municipal water to wash cars. They’ll demand proof of an official licence if an owner says they’re using borehole water.

“We’ve been clamped down on basically,” Sipo says.

“We’ve had a lot of our equipment taken from us, even equipment that is not water tech. Like vacuum cleaners, dustbins, things that aren’t related to water, based on the fact that we are operating possibly with using normal potable water.”

(Video: This man could face fines if he's found to be using city water to wash cars at his operation on the side of the road near Mfuleni township.)

Sipo insists that he is not, although it’s clear he knows his tale might be a little on the tall side.

He says the narrow hose peeking up out of the dirt beside him is not attached to underground pipes, but rather to a borehole in his uncle’s yard in the township in the distance.

Dry car washes that use special sprays are all the rage in downtown Cape Town car parks, promising a “scratch free wash,” but Sipo says those sprays are too expensive.

He says he wishes the police would treat his operation like a real business and offer some help.

“It’s not really a business you can get rich on,” he says. “But it’s something that will keep you off the streets. It will keep you from doing crime.”

People in the townships say the focus on car washes in the settlements is hugely disproportionate given how much water is used in parts of the city like Constantia or Camps Bay, playgrounds for tourists and the rich.

The police insist they are working all parts of the city. The same teams handing out fines to illegal car washes are responding to calls from people reporting on their neighbours for watering their lawns with municipal water.

Authorities say they're installing 3,000 “water management devices” a week on properties suspected of consistently using too much water.

“We go to the area on the outside of your property and we install a restrictor,” says Richard Bosman, the man in charge of Cape Town’s emergency response to the water crisis.

“We restrict you to 10,000 litres per month, whereas you were using 20 or 30,000."

It still doesn’t reduce the sense of injustice for so many who have never had easy access to water and sanitation in their daily lives.

IV. Enduring inequality

Sibusiso Nozigqwuebe came to Cape Town from the Eastern Cape in search of work and found a job as a security guard.

He lives in an informal settlement in the township of Khayelitsha, with his wife. They use a communal pump for their water, carrying it in buckets to their small shack for drinking, washing and doing dishes.

The bucket that hotel owner Mariehette Davel now uses to wash with most days, and says is a “leveller,” has been the couple’s permanent reality.

There’s a bank of communal toilets by the pump, but there’s no running water and they’re afraid to use it at night.

“Between this area and the Cape Town where there’s whites, it’s quite different,” Nozigqwuebe says. “Because there, they’ve got enough water. While here, we get a little small water. And they are telling us that we must use water wisely, you see.”

Musa Gwebani, head of programs at the Khayelitsha-based Social Justice Coalition, says it’s simply not possible to discuss the crisis without also talking about race.

“I think that if we were to try and avoid those things, to try and avoid the class, the race, the inequality, then we’re not having an honest conversation.”

Gwebani has lived both in rural South Africa and in an informal settlement, where she says 50 litres of water per day would be considered a generous helping.

She says the city’s messaging on the drought has been off for the poor.

“Catch the water off the roof. Dig boreholes in your garden. Flush your toilet less!

“Poor people don’t have those measures and the poor people in this country are black. And those things are not accidents. We inherit that from our history.”

The people’s right to sufficient water is actually enshrined in South Africa’s constitution.

But the crisis in Cape Town has highlighted the issue in a way that the persistent lack of water in other parts of the country, and in the city’s own impoverished settlements, never had before.

"I think we need to make sure that while we are tending to Cape Town, we need to remember other areas and do something about it,” says Koketso Sachane, a popular radio host on a network called Cape Talk.

“There are some who argue that because it’s Cape Town, because it’s considered to be European or the last outpost, the response will be quicker because we’re talking about white people possibly running out of water.”

The water crisis has also highlighted concerns over the potential privatization of water and what that might mean for South Africa’s disenfranchised.

A majority of the country's dams are privately owned.

One reason Cape Town managed to delay Day Zero was a “donation” from surrounding farmers, who diverted some of their private reserves to the city’s dam system.

South Africa is still struggling to address the racial disparities in land ownership left behind by apartheid. Most of the land is still owned by whites.

Ironically, the impoverished Cape Flats sit on one of the main aquifers Cape Town is hoping might ease its water problems down the road.

Day Zero may be floating back and forth in the calendar, but it's not going to disappear, experts say.

“We need to realize that Cape Town has become a water stress area and this is going to be a long-term issue. It’s a mindset issue we’re looking for,” water crisis manager Richard Bosman says.

The city has made dramatic strides, reducing its water consumption by half since the drought began in 2015.

But despite all the publicity and all the signs plastered around town urging people to save water and that “Every drop counts!” more than 50 per cent of the population is ignoring the city’s recommended consumption levels.

Sacrifice is in the eye of the beholder.

Read more stories about Water at Risk:

- Nobody knows exactly what's next for Cape Town's water supply

- 'It's not impossible': Western Canada's risk of water shortages rising

- Stop-start showers, dry shampoo and plenty of hand sanitizer: How Cape Town is weaning itself off water

- What living on 50 L of water a day looks like

- Read all the stories in the series

Coming up:

FRIDAY | Shrinking mountain snow pack spells trouble for Vancouver: CBC meteorologist Johanna Wagstaffe and science reporter Emily Chung explore threats to water on Canada's West Coast.

SUNDAY | CBC Mideast correspondent Derek Stoffel explores what happens when the need for water butts up against the complex and thorny politics of the Middle East.