April 15, 2021

Gently, Esther Teodoro rubs her husband Eduardo's forehead, smoothing out his salt-and-pepper hair as he lies in his hospital bed.

"You're going home, OK?" she tells him. "I can take care of you, OK?"

Eduardo can't respond. He has a breathing tube, just one part of the complex web of medical equipment keeping the 75-year-old's battered lungs and body functioning as he struggles to recover from COVID-19.

Esther, his wife of 38 years, was infected at the same time back in January, but her illness was mild. Now likely protected from reinfection, she's a rare visitor allowed within the Scarborough Health Network's Centenary Hospital intensive care unit in Toronto's east end.

"Ed? Ed?" Esther says, more urgently, from behind her pale blue surgical mask.

"Are you in pain?"

Her husband winces, his face scrunching up as his eyes shut while his mouth gapes open in what looks like a silent scream.

Pain, here in this hard-hit hospital network, is everywhere; felt by the patients, their families, the burnt-out staff, from the gatekeepers in the emergency department to the around-the-clock critical care teams.

As the pandemic's third wave is sending a surge of patients into hospitals across Canada, the dire situation in Scarborough reflects broader inequities and missteps that pushed some regions to a crisis point — all while vulnerable patients bear the brunt of infections and front-line workers strive to bring the health-care system back from the brink.

The surge

It’s 11 a.m. on April 8.

All at once, phones start buzzing and ringing throughout the intensive care unit, breaking up the monotony of gentle, constant beeps from each patient suite.

"A stay-at-home order is in effect," reads Ontario's latest emergency alert, signalling the start of a heightened lockdown across the province after a stretch of rising COVID-19 case counts and record-breaking critical care admissions cut short provincial reopening plans.

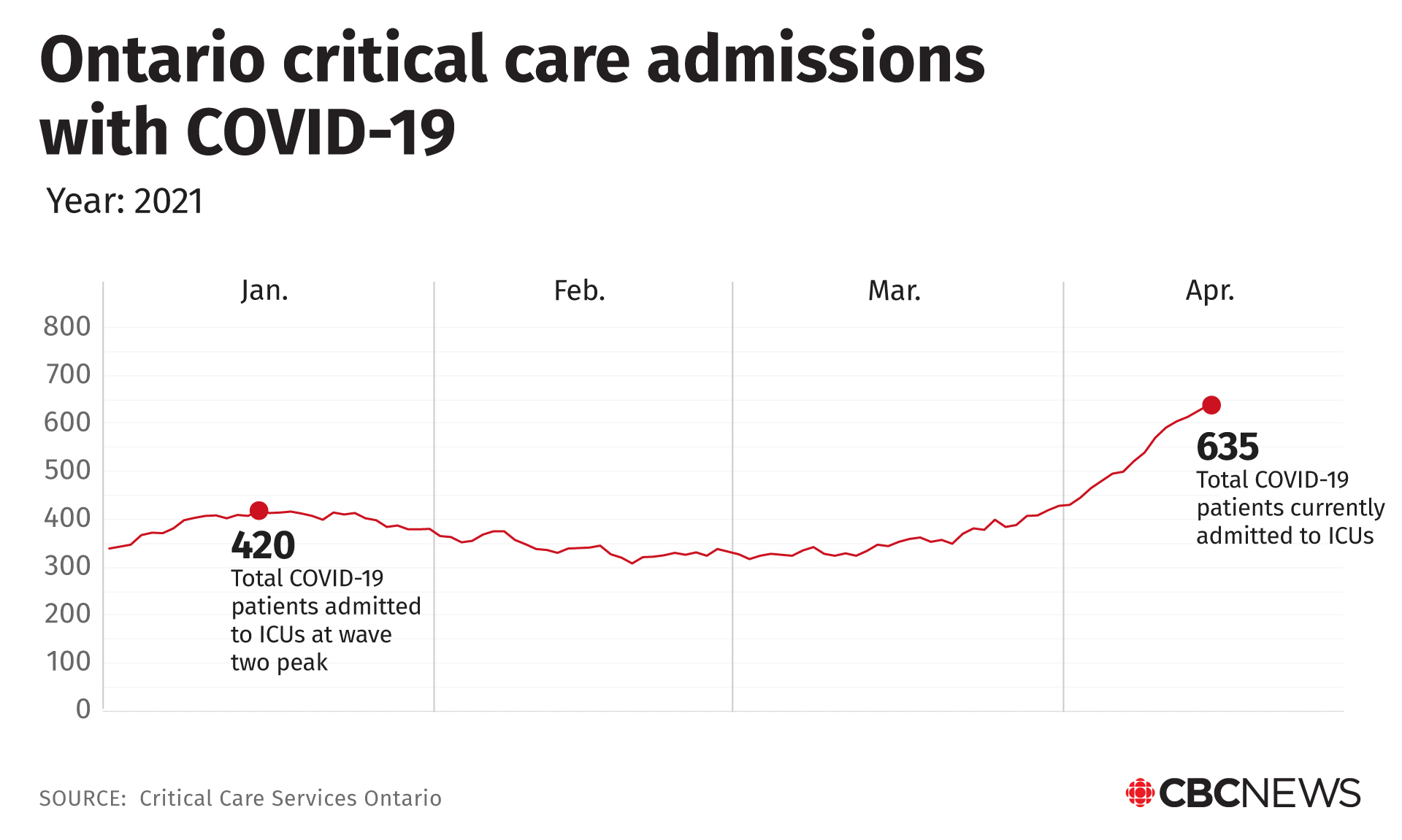

On this day, more than 500 patients with COVID-19 are in critical care units across the province, including 24 here at Centenary Hospital, filling the majority of the available beds. Just a week later, the provincewide tally hit 635.

Lorraine Pinto, a soft-spoken social worker who helps patients' families navigate their loved one's critical illness, stresses that many of those being admitted simply can't stay home as the province requests.

Often, people getting infected are essential workers, she says. Many bring the virus back to multiple generations living under one roof.

"Imagine someone just like you and me who was functioning very well, may have gone to a job in a factory, contracted COVID, maybe in their 40s or 50s."

WATCH | How COVID-19 spreads through families, striking multiple generations:

Health care workers at the Scarborough Health Network in Toronto’s east end explain why they’re now seeing entire families getting infected with the virus behind COVID-19.

Across Toronto, those trends have been clear for months, with outbreaks popping up in all kinds of indoor settings deemed essential, including schools, food processing plants, shipping centres, factories and manufacturing facilities. And people of colour are bearing the brunt.

The vast majority of cases reported across the city — roughly 76 per cent — have been among people who identify as a "racialized group," according to the most up-to-date demographic data available from Toronto Public Health.

And, after adjusting for age, the hospitalization rate in the city's lower-income population is roughly three times higher than the rate among residents in higher financial brackets.

Patients recently admitted to the Centenary ICU are of various backgrounds and ages, including one man in his 50s who's being cared for by longtime registered nurse Jose Pasion inside an isolation room while the team awaits the results of the patient's COVID-19 test.

After carefully removing his protective gloves and gown, Pasion exits through the room's sealed door. It's striking, he says, that he's now caring for critically ill patients who are often in the prime of their lives. Recently, the team has even started treating some young adults in their 20s and 30s.

"In the first wave we saw a lot more older ones," he says. "But this trend in the third wave, younger generations are pouring in."

WATCH | What it feels like to put eight patients on ventilators in one night:

Dr. Martin Betts, medical director of critical care for the Scarborough Health Network, explains the heartbreak of intubating eight different COVID-19 patients all in one night.

Dr. Martin Betts, medical director of critical care for the Scarborough Health Network, points to widely circulating virus variants, which can spread rapidly among family members.

"So far in Wave 3, we've admitted seven husband-and-wife couples," he says. "I think it's a sign the virus is getting into homes, infecting everybody, and because it's so much more powerful than the previous virus, more people are coming into hospital together."

On a recent Saturday, Betts put eight patients with COVID-19 on mechanical ventilators back-to-back overnight, the most intubations he's ever done in one shift during his career as a physician.

"And the hardest part of all of it was the conversations before having to do so, and seeing them say goodbye," he says.

"Because we know they're going to be on a ventilator for some weeks, in a medically induced coma so we can provide mechanical ventilation, and we know probably half of them aren't going to survive."

The pressure

At Scarborough General Hospital, a 10-minute drive from the Centenary site, Betts meets up with a separate intensive care team that's preparing a patient to be transferred to another hospital, all to free up one more much-needed bed.

The patient's final destination would have been hard to imagine before this pandemic: a new adult ICU at Toronto's Hospital for Sick Children, a downtown pediatric facility typically known as SickKids.

The eight-bed unit for people roughly 40 and under was planned for use only "if needed," the hospital announced on April 6. It began accepting patients two days later.

At the same time, more than a dozen other hospitals are shuttering pediatric wards, and transferring ill young patients to SickKids as well.

Inside Scarborough General's ICU, a two-person team from Ornge, Ontario's non-profit air ambulance service, is gliding their stretcher-bound patient — who can't be identified for privacy reasons — through the hallway.

Both paramedics are wearing the highest level of personal protective gear, including full gowns, rubber gloves, shoe coverings, either goggles or a face shield, and industrial-grade masks like those you'd see on someone working with hazardous chemicals.

"Could you get the elevator?" one paramedic asks a hospital worker, his voice muffled by his mask.

While the patient's destination might be unusual — an adult, heading to a children's hospital — shuttling critically ill patients around Ontario to boost capacity in maxed-out hospitals is now the norm.

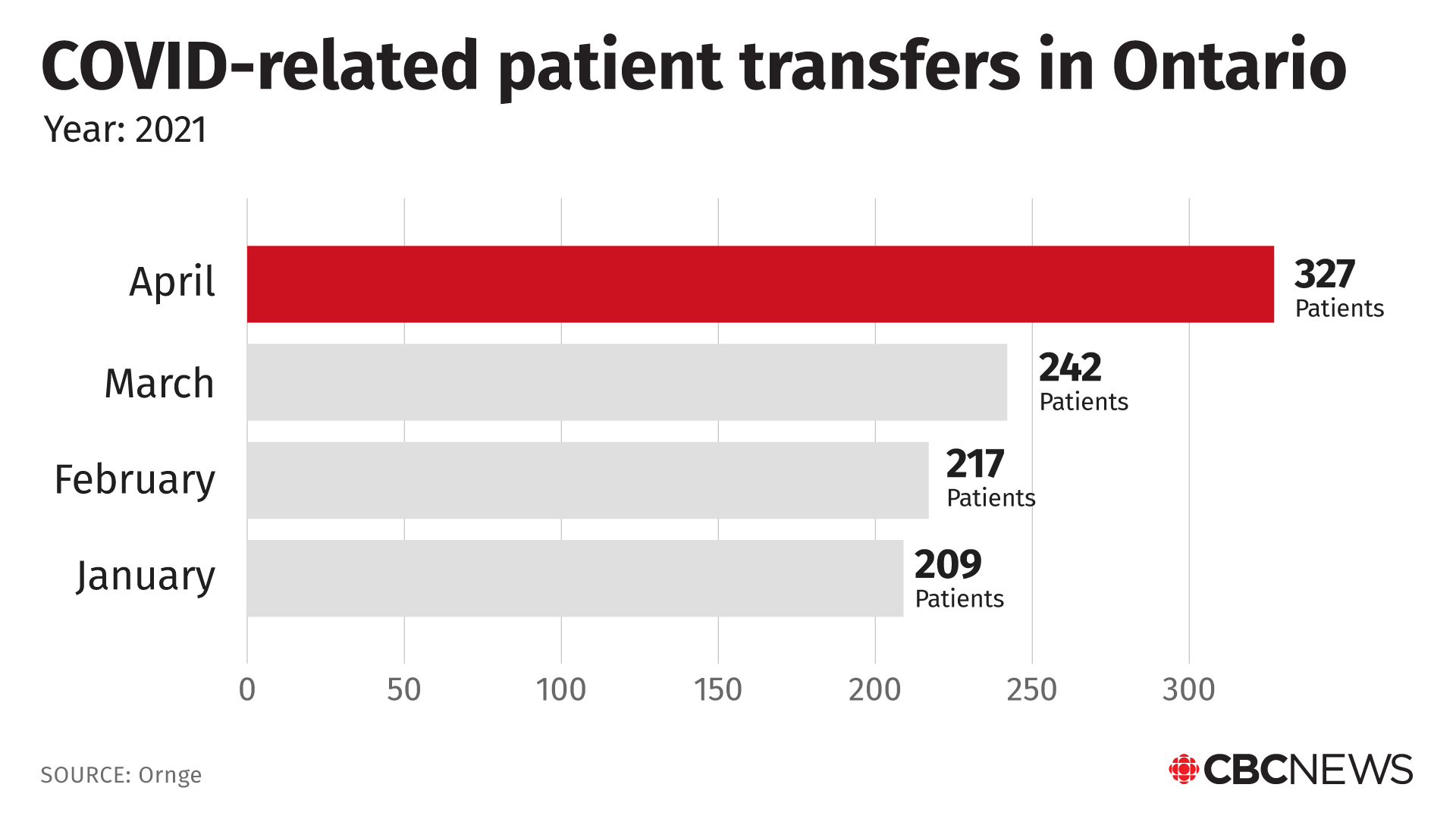

Already this year, nearly 1,000 patients have been transferred across the province because of the strain placed on ICUs from COVID-19, Ornge data shows.

Sometimes, like today, it's within the same city, close to a patient's loved ones. In other instances patients are being shuttled from Scarborough to cities like Kingston, Ont., a 2½-hour drive away, or from Thunder Bay in northern Ontario down to facilities in the south.

Those transfers are all part of a provincial push to ease the pressure and boost ICU capacity by hundreds of beds.

Since third wave admissions started surging, Ontario has granted hospitals the ability to transfer patients without consent, began cancelling elective surgeries, continued building field hospitals and announced an emergency order to support the redeployment of other health-care workers into highly specialized hospital sites.

Despite those efforts to carve out space, Betts says there's no quick fix.

"While those beds exist, it's been difficult to find staff, skilled staff, to be able to look after these patients," he says. "Especially 13 months now into the pandemic."

The burden

Near Scarborough General's ambulance bay, inside the bustling emergency department, patients aren't supposed to stay long. A triage system is meant to keep them moving, into beds or off for tests or back to their homes after a quick visit if the issue is minor.

The ongoing challenge is that sick people just keep coming, at a constant flow beyond what staff handled in pre-pandemic times.

"Never seen anything like it," says Dr. Norm Chu, medical director of emergency medicine for the Scarborough Health Network. "In fact, it's the worst we've seen since the pandemic started."

Chu flips through a patient chart, surrounded by the constant hum of a unit that's filled with lingering paramedics, anxious patients and staff members who barely have time to take a sip of water since doing so would mean somehow getting outside and taking off both a face shield and surgical mask. There's just no time these days.

"We're almost at our limit," Chu says.

WATCH | Dr. Norm Chu explains why COVID-19 hit Scarborough so hard:

Dr. Norm Chu, from the Scarborough Health Network's emergency department, says the community, including many essential workers and people from multi-generational homes, was disproportionately impacted during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Inside one of the few empty patient rooms down the hall, custodian Paula Clarke is diligently cleaning every surface before someone new shows up.

Clad in protective gear, she starts wiping down a cart and equipment with towels soaked in bleach. You can't skip a single touch-point, she says, given the high turnover of patients and the chance that any one of them could have COVID-19.

"My mom died with COVID," Clarke says, "so I have to make sure everything is done properly."

It's a burden she carries during every long, tiring hospital shift after her mother died of her infection during the first wave last year. But staying away from her job as an essential, front-line worker wasn't an option despite the pain, Clarke says. There are bills to pay.

"It's hard because I didn't get to see her," she continues, while packing up her cleaning cart. "So, you know. It's hard. But what can you do? I just saw her on the video … and she died in the evening."

Across the hallway in another patient room, a woman cries out for help. Around the corner, a man in his 50s who's struggling with numbness from a blood clot winces slightly as a nurse administers a COVID-19 swab test, just in case.

Every patient who comes through the department's doors gets tested, regardless of symptoms, says Chu, and the numbers coming back show a community that's been disproportionately affected by this pandemic.

Right now, roughly a quarter of all swab tests taken at the hospital end up positive. At a clinic that's only for patients experiencing COVID-19, cold and flu symptoms, Chu says that metric of positive tests spikes to 46 per cent, meaning close to half of all those showing up are most likely infected with the virus, and some of them will one day wind up in the ICU.

For Ontario, the test positivity rate on this day is less than 10 per cent.

"We've been disproportionately affected by COVID," Chu says. "Lots of multigenerational families, factory workers, essential workers."

Vaccination efforts may be deepening the disparities.

Recent data has shown some lower-income, high-diversity neighbourhoods, including several in Scarborough, are facing infection rates far beyond wealthier postal codes — while their vaccination rates have lagged far behind some of the city's toniest locales.

Chu calls the situation in Scarborough a tragedy. The constant flow of seriously ill people is taking a toll on his overworked staff.

And the worst stretch, he says, is yet to come.

The hope

Back inside Centenary's ICU, it's close to midday.

Esther is still by her husband's side in his sunlight-soaked corner room, despite telling staff she needed to leave by 10:30 this morning.

She struggles to pry herself away from the man she's been married to for nearly four decades, the father of the couple's two grown children, her partner since moving to Canada in 1994 who she first met while they worked together back in the Philippines. She was in a production department, and he was in the nearby art department as a graphic designer.

After immigrating to Canada, Eduardo worked for years in the types of essential roles where so many are falling ill, including stints in a factory and big box retail.

"He's a good husband and he's a good father to my kids," Esther says, her voice cracking, her eyes welling up behind her glasses. She pauses. "It's not easy. It's not easy for my family."

Eduardo's care team says he recently started showing signs of improvement. There's a chance he'll eventually be discharged. But he's not out of the woods.

Betts points to his lung scan, displayed on a computer screen nearby, showing the once-healthy organs are now cloudy, as if filled with smoke.

"Those are lungs that are not going to get better any time soon," the physician says quietly.

Esther isn't sure how she and Eduardo became infected back in January. One of her granddaughters also tested positive, she says, although the rest of the family was spared.

It's a silver lining, given how much worse things are for so many local families in this third wave, but the thought offers little comfort for Esther as her partner lies in bed, his eyes glassy.

"We're not losing hope," she says. "I know he'll be OK. I will not lose him."

Wedged in close to Eduardo's bedside, Esther whispers words of reassurance, and holds her husband's frail hand, and tells him she loves him, and that she'll keep on praying.

And she promises, again, to take him home.