October 28, 2018

Kamsack’s main street is typical of a small Saskatchewan town. There’s a Canada Post, a few four-way stops, a couple of banks and a Home Hardware.

The community is quiet, aside from two bustling pharmacies that stand less than a block from one another.

The dozens of methadone doses the pharmacies dispense daily hint at the lurking opioid crisis affecting townspeople and members of three nearby First Nations.

Frontline workers witness disturbing, widespread patterns tied to addictions: child apprehension, domestic violence, homelessness, drug trafficking-related crime and prostitution.

They also see prevailing stigma surrounding substance abuse in the town of less than 2,000.

But positive patterns are starting to shine through, as stories of recovery and resistance emerge.

The morning ritual at New Beginnings Outreach Centre involves putting on a pot of coffee. The fresh brew drips as people trickle in.

It's a special kind of coffee-row located just off the main street.

On a wintry day in early October, the centre was packed by noon, as usual. People shuffled inside, lining up for a free hot lunch — the only meal of the day for some.

Deanna Wapash took her steaming bowl of soup and sat with the day’s visitors.

Wapash used to visit the centre every day. She first wandered into its original location not long after it opened in 2016. She was curious about the free coffee and consumed by addictions.

The centre was designed to help the impoverished and close gaps in healthcare. For Wapash, it was a reason to get up in the morning. She is certain she would be dead if not for this place.

“It’s a safe place. I don’t feel scared or nervous. I feel relaxed and calm. It’s just like family,” she said.

Wapash grew up in Kamsack. She has lost almost everyone in her immediate family.

“I thought I had no one, nothing, and I just kept going down.”

She was first prescribed drugs for pain. When that supply dried up, it was easy to find the same drugs on the street.

She injected opioids and drank often. It was an “ugly life,” but it wasn’t foreign.

Ten of her 11 siblings died while caught up in cycles of addiction and violence. She also lost her parents early on. Her mom died in her sixties from diabetes and her dad of a heart attack in his fifties.

Her baby brother is the only one left. She’s trying to support him while he navigates his own addictions.

Wapash said she gave up on life after losing so many loved ones, but she's found a new path with the help of the centre’s staff.

She wishes the centre was opened sooner.

“There was no help. You’d see a counsellor on reserve and next thing people on reserve would know what you were talking about.”

The centre has moved to a larger space since 2016 because of constant and growing demand.

Peer counsellors and mental health workers are available on site. There’s also a roomy kitchen and a harm reduction space that offers education, condoms and packages of clean needles — no questions asked.

- Canada has seen more than 8,000 apparent opioid deaths since 2016

- Life expectancy in Canada may be decreasing as opioid crisis rages on

“No one really realized the impact having an outreach centre was going to have in the community,” said Wanda Cote, the centre’s manager. A sweet burning scent lingered in her office as she finished a prayer.

Initially there was reluctance within the community to engage, but trust is growing.

Cote said several clients eagerly await programming, like Monday’s traditional sharing circle, the women’s group, bannock burger bake sales, movies and even medical testing days.

Wapash has found stability she could never imagine. She’s working on her resume, ecstatic to be in the essential skills program at Kamsack’s Parkland College.

She is also trying to rebuild relationships with her kids and grandkids.

“They’re starting to forgive me,” she said.

She still sees so many other broken families.

“That’s what I pity: the kids that are suffering. I see it every day.”

Crisis state in 2016

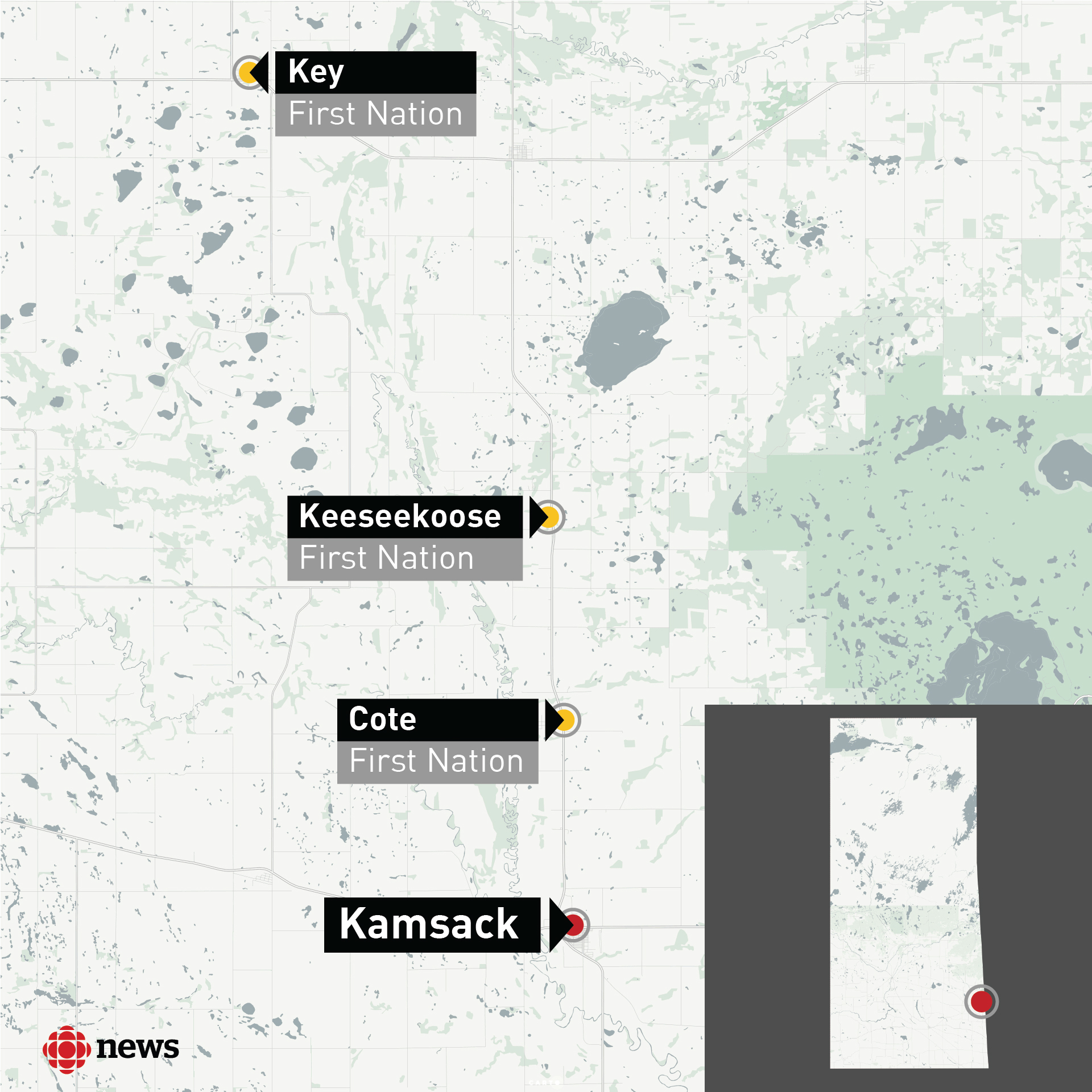

Kamsack sits next to the Manitoba border in the southeastern part of Saskatchewan, only kilometres away from three small First Nations: Cote, Keeseekoose and Key.

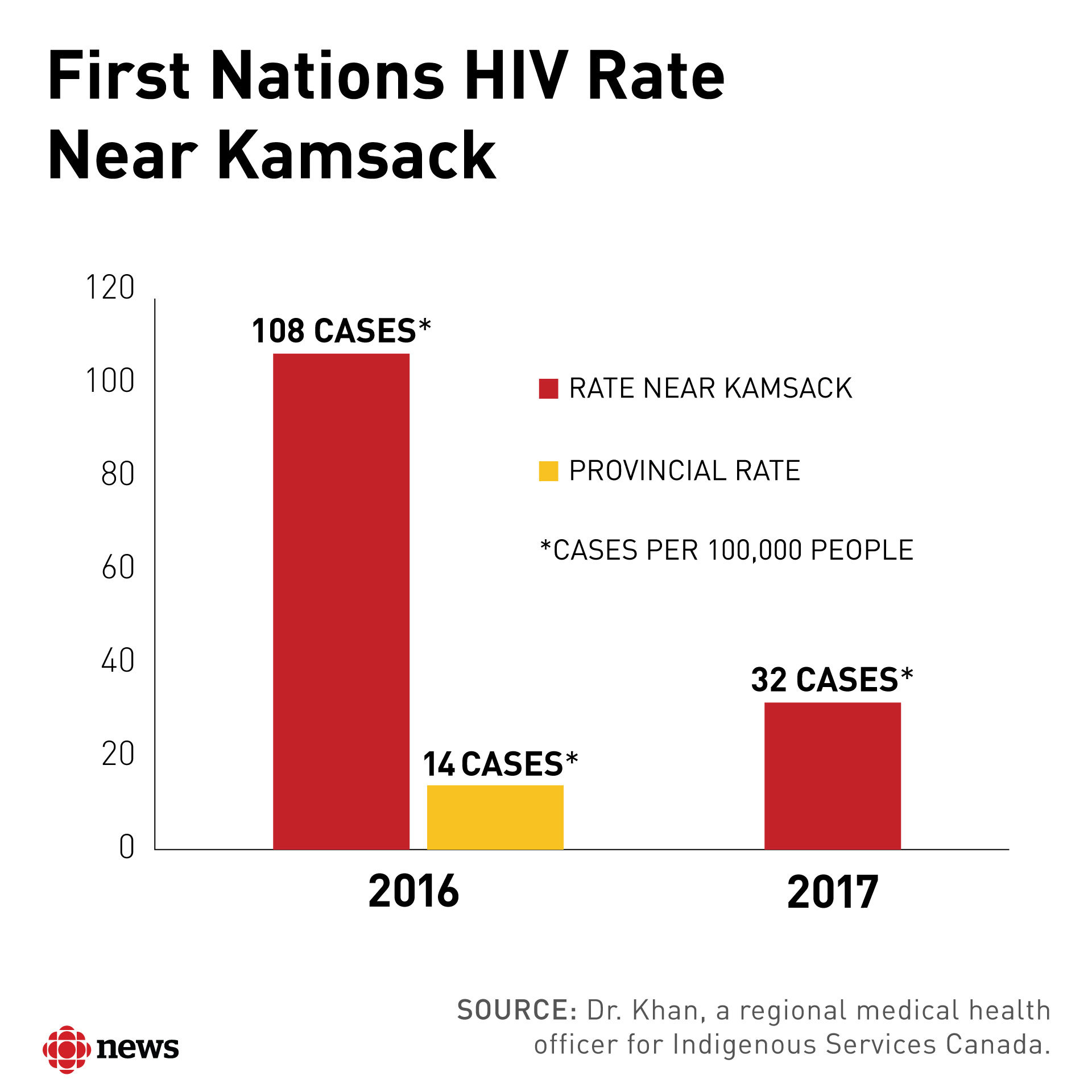

The region faced an HIV outbreak in 2016. The infections were primarily caused by injection drug use that was spreading other blood-borne infections and leading to death, in some cases.

- Saskatchewan's HIV rate highest in Canada, up 800% in 1 region

- Drug addictions, overprescription need government help: Sask. First Nations

That unsettling gap between the provincial HIV rate and that of First Nations near Kamsack has since narrowed.

The co-ordinated efforts of the three First Nations, the New Beginnings Outreach Centre, the town, Indigenous Services Canada, out-of-town healthcare practitioners, the Ministry of Health and others helped curb the HIV crisis.

Testing, treatment and preventative education is ongoing, but Dr. Ibrahim Khan said concerns about Hepatitis C and other health complications remain.

He's a regional medical health officer for Indigenous Services Canada and said that's why addictions services and harm reduction programs must remain available.

“We need to keep the focus on addictions, and particularly injection drug use in that area,” he said.

- Number of people unknowingly contracting hepatitis C on the rise: doctor

- New HIV screening method leads to apparent spike in testing at Sask. First Nations

He said more than 90 per cent of patients with HIV, Hepatitis C, or STIs in the area had reported injection drug use as a primary factor for transmission.

The lifestyle is seemingly inescapable.

“I’d say every second person you’d pass by on the street is addicted,” said Vanessa Langan, a 30-year-old from Cote First Nation.

“I used to judge people that were IV drug users, and I turned into one.”

She sat with her friends at New Beginnings, adjusting her makeup before telling her instructor at Parkland College she would be a little late for class.

She said she has been in recovery since January, aside from a few slips.

Langan said she used drugs to cope with childhood trauma and the pain and guilt associated with the death of her partner of 11 years.

She didn’t care about anybody, including her children, while deep under the influence for more than a decade.

“I can admit it today because I dealt with that,” she said. “Their first step. Their first word. Their first hair cut. Their first bath. You name it, I missed it, just to have that drug.”

Langan wants to become a role model for her children and youth in the community. She’s tired of seeing 15-year-olds injecting drugs and wants them to know a life beyond that.

“I don’t want them to see that their whole life, and their children and so on and so on and grandchildren.”

Langan said God, the centre and an in-patient treatment centre were all critical in her healing.

It is still hard for her to quiet the voice in her head that whispers, "You need this fix." She fights it by keeping busy.

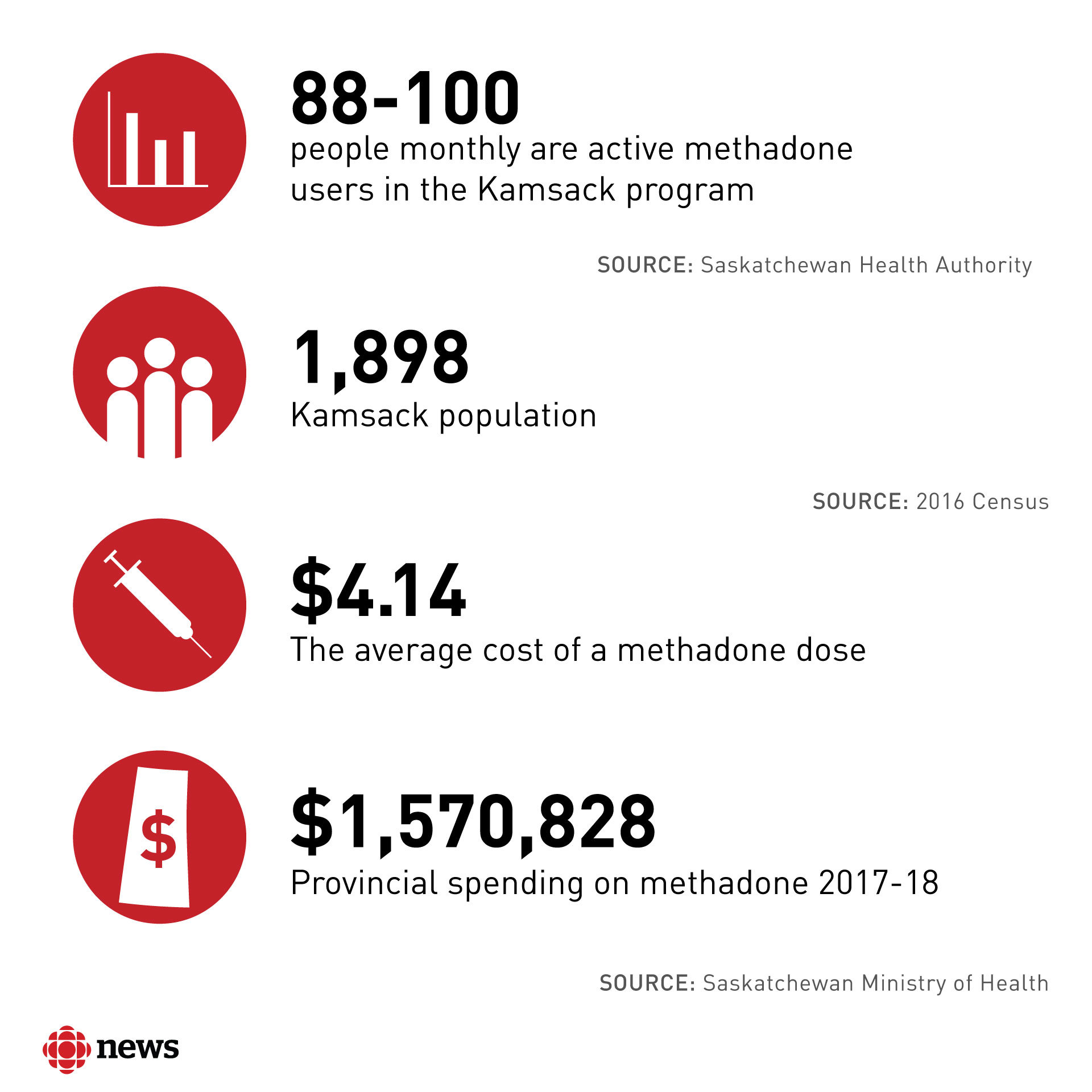

She also visits a pharmacist once a day for her 16 ml methadone dose. Langan is proud she is on such a low dose.

Depending on the month, about 88 to 110 people line up at one of the two Kamsack pharmacies for their daily dose of methadone.

Methadone dependence

Not everyone supports the program. Some band members opposed it because of the location, a lack of consultation and concerns about people getting hooked on methadone.

The program is strict. Some clients say the program holds them prisoner because they can’t leave the community and still get their dose.

- Methadone program pioneer now says it isn't working in NL

- Sask. lacks doctors willing to prescribe methadone, opioid therapies, experts say

- Why this woman credits 'liquid handcuffs' with saving her life

And staff at the centre say there are very few in-patient treatment centres in the province that will take patients on methadone.

The town has had another problem with methadone.

A Kamsack doctor had his ability to prescribe the drug revoked in 2014 at the recommendation of the College of Physicians and Surgeons.

Dr. Murray Davies was charged with unprofessional conduct four years later by the regulatory body for improperly prescribing opioids and benzodiazepine, and for not maintaining proper records.

The college is gathering witnesses to testify at the hearing. Davies is still licensed to practice and continues to do so, with restrictions.

Treatment on reserve

Cote First Nation, where Langan is from, is a short drive north of Kamsack on Highway 8.

Saulteaux Healing Wellness Centre is tucked away from the highway on the reserve, beyond a section of small houses.

There has been a lengthy waitlist since it was converted into an inpatient centre in 2016. It cannot accept patients on methadone.

Annabelle Cote joined the program in September 2017.

She grew up in Yorkton, Sask., and became hooked on drugs more than a decade ago at 17. She preferred hydromorphone but sometimes used heroin.

She said her life took its darkest turn when the father of her two oldest kids was killed under the influence of alcohol.

She then lost her grandmother, her mother and her aunt.

“I just got more and more into drugs, thinking I knew what was coming, but I didn’t.”

Not everyone completes the six-week program.

Cote did, but she relapsed after her brother died a drug-related death.

She said she has faced judgement and even resentment for her substance abuse, and that people struggle to see her beyond her addiction.

She hasn’t given up. She started the program anew in early October and is back in the familiar sunlit dining hall with dream catchers for sale on the wall.

There is tobacco on offer at the reception kiosk near the front doors, accompanied by a handwritten sign that asks users to only roll one cigarette at a time.

Elders often visit and share teachings at the centre to help clients and help themselves.

The program helped Cote love and respect herself, something she said her past made difficult.

“Sexual abuse, physical abuse. They teach you here to deal with that trauma in your life so you’re not making the same mistake over and over and over again,” she said.

She is working to get some of her children back. She wants to be the first in her family to break the cycle of addiction.

“My biggest fear is them doing what I’m doing.”

Past convictions

While some community leaders have worked to combat Kamsack’s health crisis, others have been tied to the community's drug problems.

Key First Nation’s current chief, Clarence Papequash, pleaded guilty in March 2017 to possession of codeine for the purpose of trafficking. He was a band councillor at the time.

He also previously resigned as band chief after he received a six-month conditional sentence for selling a morphine pill to a man working for the RCMP.

- Saskatchewan First Nation band councillor gets one year for drug trafficking

- 'Admitted my wrongs': Past chief, convicted drug trafficker elected on Key First Nation

"I didn't contribute to the drug problem; the problem was already there," Papequash said.

"I've got nothing to hide, you know."

Papequash said that at one time he did sell "Tylenol 3s" to support his addiction. However, he said he's "clean as a whistle today."

His brother, Gerald Papequash, pleaded guilty in 2011 to trafficking drugs. He was a band councillor then and one of several people from the area charged with trafficking prescription drugs.

Crystal meth concerns

Prescription drug dependence remains a constant, but staff at New Beginnings say a new drug has also surfaced. Some people are turning to crystal meth when they can’t get prescription drugs.

There have been violent, meth-related incidents and other worrisome situations at the centre as of late.

Wanda Cote, the New Beginnings Outreach Centre manager, said she is hopeful even with the new challenge.

She said her research indicates 22 people died because of drugs between October 2016 and May 2017.

In 2016, representatives of the Cote, Key and Keeseekoose First Nations said their communities saw about 100 combined deaths the year prior.

Cote has witnessed less death or injury in recent months, as well as less child apprehension.

She believes the outreach is helping.

"If we help one or two people it’s a big success for us.”

They feed about an average of 70 people each day and about 676 clients go through programming monthly.

Clients who move beyond the phase of just stopping by for nourishment often start volunteering.

“They are making moves to change their lives but there’s also a lot of barriers; one is the stigma from community.”

Frontline workers and users point to poverty, a lack of jobs and a lack of income as a driver of the drug trade.

Cote said combatting injection drug use and mental health problems requires a multi-jurisdictional approach.

“If the community isn’t going to make some strict bylaws regarding people who are selling the drugs, it makes our work a lot harder,” she said.

CBC requested an interview with Kamsack Mayor Nancy Brunt.

After discussing the request with town council, the mayor’s administration declined the request, saying the topic “is a health issue.”

Cote said a lack of things to do in the community, and the resulting boredom, lends itself to trouble.

"In the mornings, there's nothing to do but walk the streets."

Another option is to pull up a chair and find conversation at the centre.

The soft buzz at New Beginnings most often eases up mid-afternoon, but the centre never empties.

People continue to drift in and out while others prepare for the next guaranteed wave of those in need.