August 15, 2019

As Kugluktuk’s 10 p.m. sun shines through her living room window, 29-year-old Megan Klengenberg is monotone and numb as she tells the story of how she became a single mother and widow a little more than a month ago.

It was a cool July evening when Klengenberg left her three young children with a babysitter and went out with friends in the Nunavut community.

A few hours later, she got a call.

Her spouse, Justin Pigalak, had come home drunk and aggressive and tried to get in the house. When the babysitter locked the door, he broke a window. That’s when the babysitter called the RCMP.

Klengenberg says no one came.

Klengenberg came home, put her children in her truck and parked up the road. She says she was scared of what Pigalak would do to her and her children, but also to himself.

She says that’s what she told police, calling them six times over a span of the next three hours while Pigalak was in the house. Nobody ever came to help, she said.

“I told them my kids were crying and we were scared. We didn’t really have a place to go.”

The next morning, after staying at a relative’s house, Klengenberg and her three children went home.

She found Pigalak lying in their bedroom. He’d taken his own life.

“I know he didn’t want to die, it just went too far,” she said.

Klengenberg’s story is just one of a handful over the last eight months that have slowly soured the relationship between the RCMP and the western Arctic hamlet. Many residents say the fracture began last October, when the community voted to lift restrictions on purchasing alcohol. Those restrictions were officially lifted in December.

Within the eight months following the restrictions being lifted, community officials say there have been eight alcohol-related deaths, including Pigalak's.

“I believe if [RCMP] just answered their calls he would still be here,” Klengenberg said.

The RCMP told CBC they received only one call to Klengenberg’s home. They responded but say Pigalak fled and officers were “unable to locate him.”

But Klengenberg provided CBC with call logs showing she made six calls to the RCMP’s emergency line between 1 a.m. and 3:55 a.m.

Like dozens of other remote communities across the North, Kugluktuk has had heavy restrictions on buying alcohol for years in an effort to curb binge drinking and alcoholism.

It was a narrow victory for those wanting to lift the alcohol restrictions. Sixty-one per cent of voters were in favour, just slightly more than the 60 per cent threshold needed.

Many Inuit said the restrictions felt colonial and brought back painful memories of outsiders telling them what they can and can't do.

Without restrictions, community members can now bring in as much alcohol as they want, when they want.

As a result, the RCMP say they’ve seen calls to the community’s detachment increase by 55 per cent since the restrictions were lifted.

It’s not just the number of emergency calls that has increased. So, too, has the community’s population.

In 2012, after a review of policing in the community, the RCMP removed one of six officers stationed in Kugluktuk. At the time, there were 1,200 residents. Now, there are more than 1,600.

“There needs to be more officers,” Klengenberg said.

To protest what she calls a “lack of response” from the RCMP, Klengenberg made signs reading “Justice for Justin” and put them up around the community.

“He was a mechanic, a really good father. He was a hunter and supported us.”

Late last month, Klengenberg was one of a handful of community members who staged a protest outside the community’s detachment.

The protesters said they had lost trust in police after more than a dozen incidents where police have been accused of not responding to calls.

“I went there and I stood there because it’s not fair. [Justin] was loved and he’s still loved,” she said.

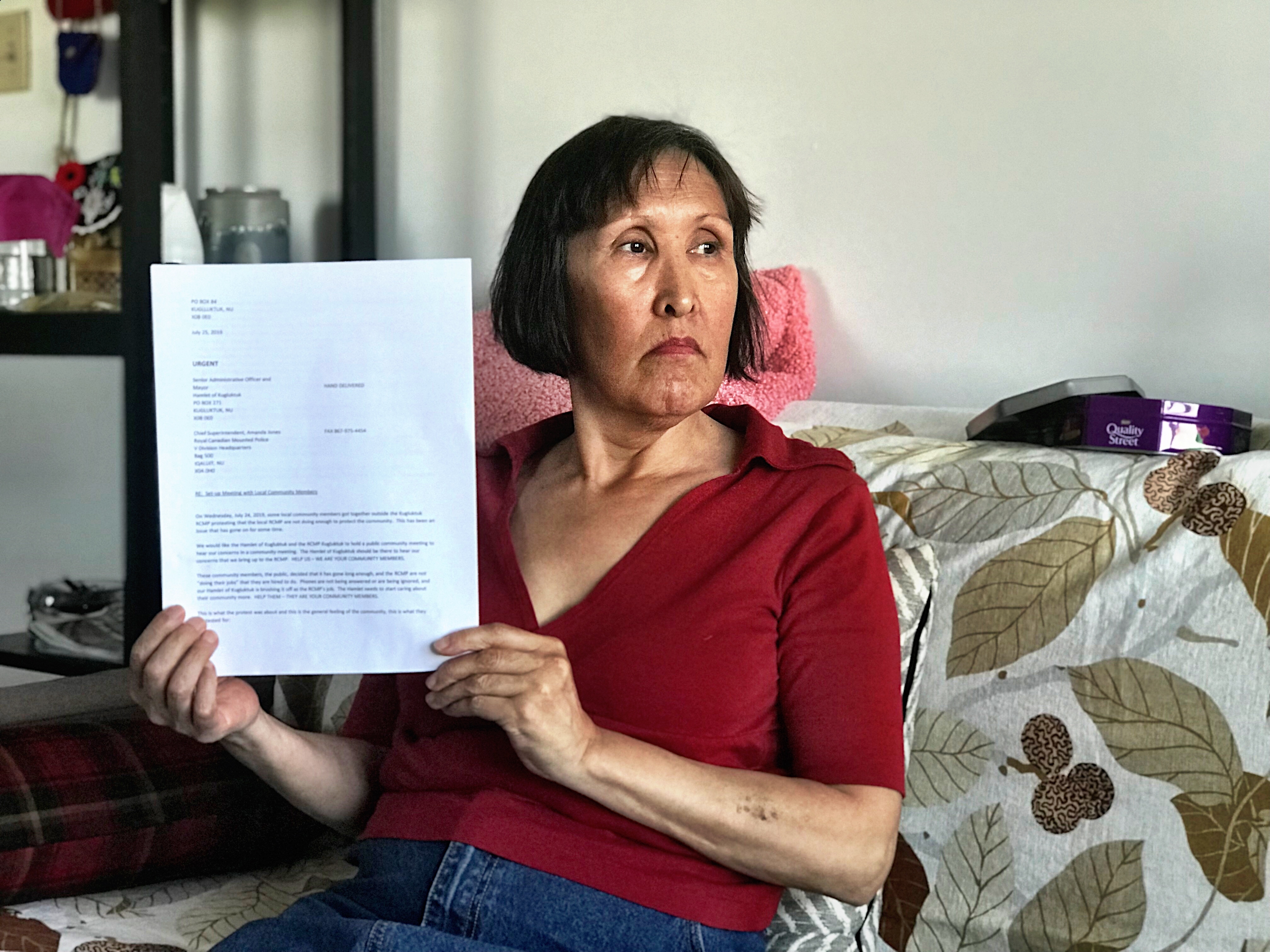

That demonstration prompted community member Barb Adjun to write a letter to Kugluktuk’s mayor, the region’s MLA, the territorial government and the head of Nunavut’s RCMP calling for an emergency public meeting.

Adjun says last month, she called the police late at night when an intoxicated man tried to break into her home. She says police didn’t respond, but called her the next morning to see what happened.

“Drunk people do bad things,” said Adjun. “People are trying to report them and they are not being heard.”

On Aug. 2, a week after Adjun sent the letter, about half a dozen government officials and the head of RCMP’s “V” Division, Amanda Jones, travelled from Iqaluit to Kugluktuk.

More than 100 residents attended the meeting, sharing their concerns and calling for a larger police presence.

“We have seen a drastic increase [in calls], since December,” Jones told CBC.

“We’re not clear as to why the delay in [responses]. I think we need to scrub down a little bit more on that.”

Jones said part of the problem may come down to a miscommunication, with community members believing the detachment is staffed 24/7 when it is not.

She said residents need to call the territory’s emergency line if they need help after hours, not the detachment. That number will be picked up by someone 2,100 kilometres away in Iqaluit, who will then notify officers in Kugluktuk if it is an emergency.

But that system is not without problems. Several people in Kugluktuk, including Klengenberg, say they often have trouble getting through to a dispatcher, and when they do, dispatchers don’t know the culture or layout of the community.

Jones said local dispatches in Nunavut are “just not feasible,” given its size, but renewed a commitment to ensuring Kugluktuk’s detachment is fully staffed.

The relationship between the RCMP and the community hasn’t always been so volatile.

In April 2018, RCMP Const. Graham Holmes died when his snowmobile went over a cliff outside the community. His fiancée, Kelsey Foote, told CBC she was shocked and overwhelmed at how the community supported her.

Seventy-five people held a candlelight vigil outside the detachment, and dozens drove their vehicles in a procession past Foote’s house.

While many community members say the RCMP has a role to play in their frustration, others also believe residents need to take responsibility.

“The people have to accept and acknowledge the issues that they themselves have,” Don Leblanc, Kugluktuk’s senior administrative officer, said.

Leblanc said the hamlet council and representatives from the Nunavut government are meeting this month to look at creating wellness programs in the community.

“Would we love to turn the clock back and switch off the plebiscite? We would love to,” he said. “People come to me saying: ‘Have them reverse it.’ We cannot reverse it.”

Leblanc said under the law, the community can’t hold another plebiscite on liquor restrictions until 2021.

At the Klengenberg house, about half a dozen young boys hover around a broken bike in the front drive. Two “Justice for Justin” signs hang behind them.

Inside, Klengenberg begins going through boxes of clothes. Her family moved houses a week ago.

“I couldn’t stay there knowing what happened,” she said. “I’m trying to be happy. It’s hard.”

Finding forgiveness, Klengenberg said, will be even harder.