August 14, 2018

Grass and brush gently crunch under Shannon Coleman’s feet as she walks over the spot where her house once stood.

“It was just a small two-bedroom, nothing fancy,” she recalls, while pointing out the spots her neighbours’ homes once occupied.

Coleman, 55, was born and raised in Fort Smith, N.W.T., a town of about 2,500 people just north of the Alberta border on the Slave River.

Today, the area where Coleman stands is covered with trees and lush greenery. There’s a walking path just outside the centre of town, with a lookout to scan the rapids below.

But 50 years ago, before a catastrophic landslide, it was home to dozens of families and a thriving Indigenous community known as the Indian Village.

On the evening of Aug. 9, 1968, a landslide more than 1,000 metres wide and 300 metres deep broke away from the bank of the Slave River and hit Fort Smith with no warning.

This month, people in the town are commemorating the landslide to ensure its effects are never forgotten.

“My mother was hanging clothes on the line, and all I remember was the ground started to shake,” remembers Coleman, who was just five years old at the time.

“I could just see this house disappeared, and it was the Fergusons' house.”

Shifting sand carried two houses over the high riverbank and left a third teetering over the edge. Kay Ferguson, 54, was home when the slide took her house. She was killed — buried under thousands of tonnes of sand.

II.

Coleman describes the moments that followed as chaotic, as community members scrambled toward the spot where the Ferguson house used to stand.

“I just remember my grandfather coming and telling us we had to pack up some stuff and we had to get out of there,” says Coleman.

The RCMP immediately ordered the evacuation of all houses closest to the edge of the riverbank. More than two dozen families from the Indian Village packed up and moved. The edge would continue to shift and crumble in the days to come.

Louie Beaulieu, who also grew up in the village, was 11 years old and setting fishnets with his father in the river when he saw the landslide happen.

“The sirens were roaring, and people were driving around like crazy, just panicked,” he says.

Amidst the commotion, a search for Kay Ferguson was quickly organized. Hundreds of local volunteers searched day and night for her body.

Mine rescue teams arrived from Yellowknife and the now-defunct mining town of Pine Point to help, digging through the ruins, while above them loomed the unstable hillside, undercut by the slide and still dangerous.

“For every shovel of sand they took away, there was more sand coming in,” recounts Jeannie Marie-Jewell.

She moved to the village in 1960 with her family. She was 13 years old, pushing her niece in a stroller, when she saw the landslide happen.

“As I kept watching, you could see part of the riverbank sliding down.”

After more than three days of digging, Ferguson’s body was found, but not before the ground moved again, taking another home over the bank.

“For every shovel of sand they took away, there was more sand coming in.”

III.

The landslide, people say, also destroyed a way of life.

Dozens of families were left suddenly homeless. The majority of evacuees were placed in government housing as they waited for their houses to be hauled away from the river to more stable ground.

While Coleman says their new home was bigger and more updated than her house in the village, other evacuees were moved to cramped bachelor apartments and even tents, spread all over town.

“I’d call it scary,” says Coleman of moving away from the village. “It was just like going to a different part of the world.”

The Indian Village had been populated almost entirely by Indigenous people. Rows of houses dotted the area and a main road ran down to the river, which was a hub of community activity.

A small church sat among the homes and a baseball diamond served as a busy recreation spot.

Though the village was only a short trip to the centre of Fort Smith, residents describe it as feeling worlds away.

“We’d share a lot of our culture when we were all together, down at the river, and we really just lost that,” says Coleman.

The relocation split up families who’d spent years living communally along the river and, for many, made it more difficult to live a traditional way of life.

“There [were] all kind of smokehouses there because everybody lived the traditional way,” recalls Beaulieu. “Women making moose hides, cooking over the fire. It was a busy place.”

Marie-Jewell remembers kids playing in the water, people checking their fishnets, having each other over for tea.

“You’d hear all the laughter all the time,” she says regretfully.

“None of these practices were continued after the landslide because we were all placed in different areas of the community.”

IV.

Marie-Jewell thinks her life would have turned out quite differently if the landslide hadn’t happened.

“I probably would have been more culturally-oriented, for sure,” she says. “Who knows? I could have probably spoke and understood my language better.

She also says that residents would have been happier today because she believes "every survivor of the landslide that evening of August 9 was traumatized.”

Coleman says the trauma manifests itself in many ways, including the fear of another slide. Fifty years later, she still refuses to go down to the river on her own.

“I believe that every survivor of the landslide that evening of August 9 was traumatized.”

While no one knows exactly what caused the landslide, there have been a number of theories, including melting permafrost and low water levels.

The hillside has since been gently sloped to stabilize the bank, and the town has deemed the area a “no development zone.”

“There is really no risk,” says Keith Morrison, Fort Smith’s senior administrative officer.

The town is hoping to slope more of the bank in the coming years to further reduce the chances of another landslide. It recently received money from the federal government to slope all the areas within municipal boundaries.

V.

Marie-Jewell, Beaulieu and Coleman have been working with a group of survivors and community members to commemorate that tragic day and make sure no one ever forgets what happened 50 years ago.

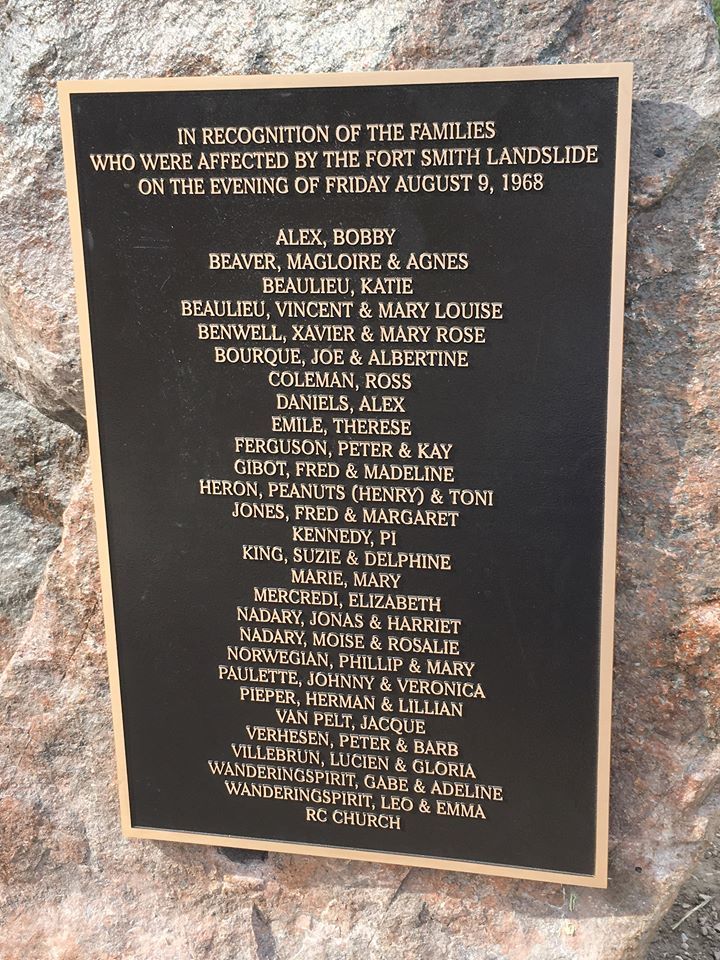

Last week, a commemorative plaque with all the affected families’ names on it, and a bench dedicated to Ferguson, were unveiled at the site of the landslide.

The group also published a book detailing the memories of the Indian Village residents from that day, and from their time living there.

For Marie-Jewell, marking what happened is one important step in the healing process.

“I guess when you look at healing, and when you look at events like this, it’s a matter of having the time to respect what has happened,” she says.

“And taking the time to make sure that’s done.”