March 15, 2018

There are days when Phoebe Walker’s only reason for living is to spite the men who made her wish she was dead.

Pale and thin, wrapped in an old sweater, she sits inside her rural Newfoundland home, a long way from the city streets she walked as a child being trafficked for sex.

In the corner, a wood stove produces the only heat available for the 26-year-old mother since the utility company cut her power almost two years ago.

“I don’t need much,” she says, with teary eyes and a smile.

Her daughter is 150 kilometres away, living with a grandparent and waiting until her mother can provide the life she deserves.

On these winter days, she fights a cold loneliness.

Her life appears to be in shambles. But to her, this house on the northern shores of Conception Bay is a slice of heaven compared to nights she sold her adolescent body on Duckworth Street in St. John’s.

Or the pornographic photo shoots in the basement of a grimy downtown pizza shop.

For 12 years, Phoebe Walker has been reduced to her initials — a non-identifier spread across thousands of pages of court documents to protect her identity after a childhood lost to sex crimes.

But now she wants you to know her name so you can know the teenaged girl that put two sexual predators behind bars, so you might feel the pain of living with those memories, so you will know her nightmare didn’t end when the verdict was reached.

But there’s something we need to tell you about Phoebe Walker.

It is not her real name.

There are two women in this story, who spoke to CBC News on the condition of having their identities revealed more than a decade after the trauma they endured.

They wanted to lay speculation and rumours to rest and show the public what childhood sexual exploitation did to their lives.

But we are not allowed to tell you what their real names are, and we cannot show their faces.

After one year of fighting, CBC News lost a court challenge to overturn a publication ban and use their identities.

“I feel like the same court system that failed us as children is now victimizing us as adults,” said the second woman, whom we will call Sarah Gallant.

Nonetheless, they are determined that you know their story.

II. — The photographs

It is Christmas Eve, 2005.

In previous years, Phoebe Walker would have been home with her family, preparing for the thrill of the next morning.

But this year, while the rest of St. John’s is aglow with holiday spirit, the 14-year-old girl has her clothes off alongside a 15-year-old friend in the basement of Big Bite Pizza on Water Street.

Standing in front of her, an overweight, bearded man directs the girls as he clutches his Sony digital camera.

Take off your shirt.

Take off your pants.

Spread your legs.

Touch each other.

Mehnad Mahmoud Shablak managed more than a pizza place. He controlled these girls as they satisfied his taste for young women.

The man known around the shop as “Mike” was seen as a fair manager when he started work in the spring of 2005. A 30-year-old student pursuing a career on ships, he was charming, too, despite some difficulties with the local language.

Shablak immigrated to St. John’s from Kuwait, by way of Egypt, in 1997, and lived in a small house on the southern shore of Quidi Vidi Lake.

According to a coworker, Shablak started flirting with young women two months into the job. He began hiring young girls who lived on the streets.

'I should have known there was something off about it.'

Sarah Gallant was 15 years old and a runaway when she started work at Big Bite Pizza.

At the end of each night, she would be paid in cash.

“I should have known there was something off about it,” Gallant said. “But I was so young. I was just happy to have an income.”

She remembers the girls hanging around the shop. She thought it was strange, but befriended some of them, including Walker.

Little did they know at the time, their friendship would become a lifeline through the decade of trauma, abuse and near-death experiences that followed.

A street kid like Phoebe Walker, Gallant ran away from home when she was 14.

Each time she returned to her house, there would be some kind of explosive episode. The police would be called. Gallant would be taken to the youth detention centre in Whitbourne, about 90 km west of St. John’s, where she remembers being stripsearched and placed in holding until she could appear before a judge.

When the routine became too much for her to handle, she stopped going home.

Big Bite Pizza became both a hangout and a workplace. She and other girls were paid for their time, and were fed all the pizza they wanted.

They were also fed drugs.

CBC News has spoken with five women who hung around the store as teenagers. Each one reported being given ecstasy or cocaine in exchange for nude photo shoots.

Walker said she sometimes did it just for food.

Her transformation from a happy child to an exploited one did not take long.

Watch Ryan Cooke's full-length documentary.

Phoebe Walker’s early days had been quite normal, growing up in nearby Conception Bay South. She had friends, was goofy and inquisitive, loved animals, adored her older sister and obeyed her mother.

Things began to unravel, however, when the family moved to Mount Pearl — the suburban city west of St. John’s. Phoebe craved social interaction, but had a hard time making new friends. She acted out against her mother and her new stepfather and sometimes ran away from home.

By 2002, Child, Youth and Family Services became involved. According to the family, a social worker suggested splitting them apart for a trial basis.

Their problems came to a head with a visit from police one night, said a relative who wished to remain anonymous.

The sisters spent the night in Whitbourne. Phoebe entered foster care the following day, while her sister, recently 16, was set up with her own apartment.

The family was destroyed.

III. The first time

No aspect of Phoebe Walker’s life improved in foster care.

Her penchant for running often put her on the streets of St. John’s, where she found a network of kids her own age.

When she was found, she would be returned to her foster home. In the care of strangers, she recalls facing abuse for the first time.

At one house, she said, the foster father — after his wife went to bed — would come to her room and attempt to molest her. She feared telling her social worker. She didn’t think anyone would believe her.

So she kept running, doing whatever she could to survive on her own.

Walker would later tell a court she began trading sex for money at the age of 12.

She can still remember the first job.

“I was so nervous,” she said. “I was almost to the point of overdosing on cocaine.”

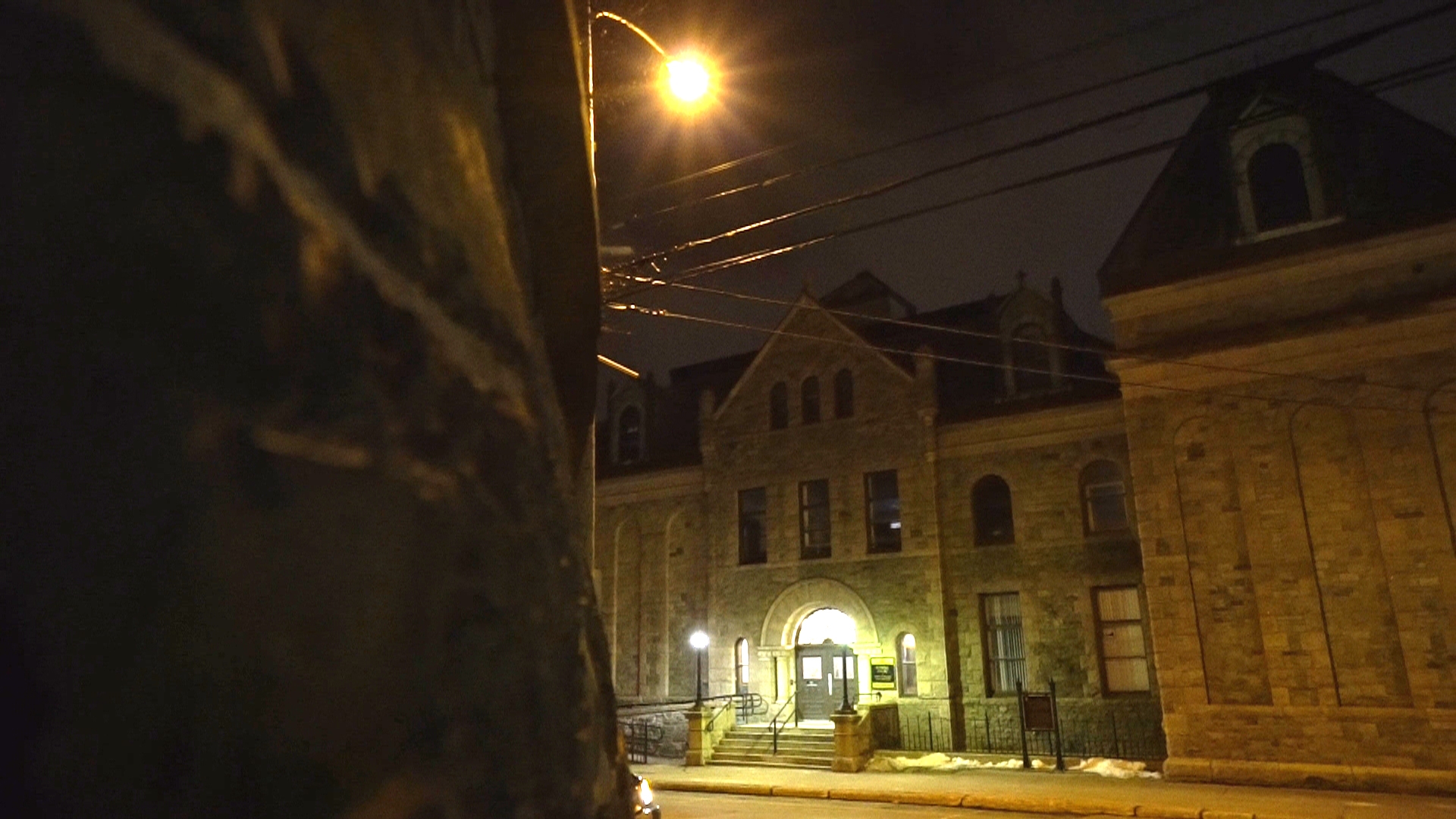

Overcome with chemical jitters, she walked uphill from the Supreme Court steps on Duckworth Street to the parking lot of the nearby Anglican Cathedral.

There, in a parked car, she endured hell.

“I remember screaming as he pushed my face down into the backseat, just begging for him to stop, begging for it to be over,” she said, crying. “It was the longest 20 minutes of my life.”

While working the streets, she met Shawn Newman — a man with attention deficit disorder and bipolar disorder who hung around Big Bite Pizza.

She developed a close bond with the man, despite being nearly 20 years his junior.

“He gained my trust,” she said. “He told me everything would be OK. He said he’d be my friend, said he loved me and cared for me … I believed him.”

While she ran from her problems, Newman circled her like a shark. He became her comfort blanket during a time of turmoil. He also became her worst nightmare.

At age 14, Walker was staying with Newman as they shared a vicious addiction to crack cocaine and lived off the profits of him trafficking her.

IV. Who knew?

It all happened in full view of the public.

Incredibly, some of it happened near the front door of the Supreme Court building on Duckworth Street.

Walker often lied about her age, but she never hid away. She worked in plain sight of passing cars, pedestrians and police.

The photo shoots took place in a restaurant frequented by members of the public.

Looking back on it now, she wishes a stranger had taken the time to ask her if she was OK.

“All the people downtown in the nights, they’d walk on past with their buddies going to get drinks at the bar. How could they not know we were children?”

Some nights, Gallant found shelter beneath the stairs of a building on Water Street. In her state of desperation, daily cash payments from Big Bite Pizza were a godsend.

Gallant had been working at the pizza place for the entire autumn of 2005 before being approached by Shablak and another male employee for a photo shoot.

She remembers rejecting their offer a few times, before eventually giving in.

On Nov. 12, 2005, Gallant posed for 25 pictures in front of Shablak and his camera.

The other male employee, whom she knows and can identify, was also present for the photo shoot, she said.

Gallant recalls being confused by what transpired. She knew it was wrong — so why did she do it?

“I know intellectually it wasn’t my fault,” she said. “I know I was a child, I was underage and I was being groomed by two adults.

“But you still deep down feel like it was your fault.”

V. Stories spill out

Mehnad Shablak couldn’t keep a lid on his secret business.

The Royal Newfoundland Constabulary’s first indication was a tip from Child, Youth and Family Services on Jan. 19, 2006.

Three days later, a former employee of Big Bite Pizza told police he quit his job after walking in on a 15-year-old girl putting her clothes on behind the counter while Shablak held a digital camera.

He claimed Shablak had bragged about his collection — thousands of photos of young girls uploaded to his computer at home.

On Jan. 24, police seized a hard drive, 143 floppy disks and 87 CDs belonging to the pizza shop manager. They pulled him in for an interview, where he asked for a lawyer. After speaking with counsel, he confessed to having images of naked girls on his camera, which he kept at Big Bite Pizza.

Three weeks later, on Valentine’s Day, Walker was taken to police headquarters and interviewed at length.

She identified 60 photos of herself — mostly nude, including one image of her being penetrated by the fingers of an unknown male.

The hardest part, she said, was looking through hundreds of images and scrutinizing each headless body to identify the others.

Aside from her own photos, Walker identified two other girls.

Sarah Gallant remembers being invited to sit in the front seat of a police cruiser by a male cop sometime in early February.

Overcome by guilt and shame, she sprinted from the car before giving a statement.

In the coming days, her mother worked with police officers to identify her 15-year-old daughter in 25 photos.

On Feb. 7, then Royal Newfoundland Constabulary chief Richard Deering held a press conference where he addressed the investigation — and revealed a shocking detail.

Police believed as many as 40 children were involved.

“This investigation has huge potential to go beyond the bounds of Newfoundland and Labrador,” he said.

On Feb. 22, Newman was arrested in the back of a taxi headed for the city’s west end. He was taken downtown and interrogated.

The next morning, Newman and Shablak were paraded through provincial court in front of the flashing cameras of every media outlet in the city.

Newman faced charges for pimping out two girls — Walker, then 14, and another 16-year-old.

Shablak was charged with six counts of making child pornography for photo shoots with six girls between the ages of 13 and 16.

Ahead of the trials, police and prosecutors backed down from claims about the scope of the investigation. Deering resigned before a trial got underway. In the coming months, authorities would also establish both cases as separate entities, saying there was little or no connection between the two men — despite both cases involving Phoebe Walker, and her testimony that she met Newman at Big Bite Pizza.

Shablak rolled over quickly, admitting to taking the photos in his very first interview with police.

He was denied bail and remained in jail as he worked his way through the court process.

Newman, meanwhile, fought against a conviction by maintaining he was simply helping the girls stay safe, denying he forced Walker into prostitution or lived off the profits she garnered.

Neither girl would have to testify against Shablak — nobody would.

Shablak entered guilty pleas on all counts, and was convicted after spending 11 months in jail.

Justice Seamus B. O’Regan accepted a joint submission by the Crown and defence lawyers to grant him extra credit for his time behind bars. He was released from jail when his plea was accepted.

O’Regan said Shablak had shown remorse by pleading guilty, and seemed to have taken the first step towards rehabilitation. He also wanted to ensure the girls didn’t need to testify.

The judge encouraged Shablak to go to work in his field of study — at sea — despite a typical probation order mandating a person to stay within the court’s jurisdiction.

Mehnad Shablak’s name never surfaced in Newfoundland and Labrador again. CBC's attempts to locate him were unsuccessful.

Big Bite Pizza eventually closed its doors.

VI. Threat no more

Shawn Newman was not willing to give up his freedom so easily.

He was granted bail and allowed to remain at his Mount Pearl home during the trial, which saw the two teenage girls testify against him.

Walker’s life was changing again, but this time for the better. She made several attempts to kick her crack cocaine addiction, finally finding sobriety after a trip to Ranch Ehrlo, a drug rehab facility in Saskatchewan.

During the final stage of the program, her mother and sister came to stay with her, and to learn to live as a family again.

On the one-year anniversary of her sobriety, Walker testified against Newman. In a trial filled with hazy recollections of crack-fueled incidents, the judge found Walker’s testimony to be the most reliable.

She told the court how she met Newman, how he offered to protect her, how she would place her money in the centre console of his van, and how he would take all her money and buy drugs.

She told them how he was violent and abusive, and how on one night he threw her against a wall.

When the Crown prosecutor asked why she just didn't just leave Newman, she said, "It's hard to explain. I felt like he actually cared for me."

Newman testified in his own defence. He insisted he wasn’t living off the avails of prostitution, despite having a second phone line installed in his home with the last four digits spelling P-I-M-P.

Newman was convicted but remained a free man while awaiting sentencing — a process that was delayed until March 15, 2008.

He was sentenced to three years in prison that day, and led out of the courtroom in handcuffs, past Phoebe Walker’s sister.

"[Phoebe] is still struggling every day and that really breaks my heart because she was such a beautiful young girl,” her sister told reporters afterwards. “She's dealing with all these different challenges now, trying to get through everyday life.”

After three months at Her Majesty’s Penitentiary — an unforgiving, Victorian-era prison in the heart of St. John’s — Newman filed an appeal and was again released from custody.

He’d remain free for more than a year, until June 20, 2009, when his appeal was denied and he was ordered to turn himself in to police.

But Shawn Newman had no intentions of going back to prison.

A few hours after the ruling came down, he was found dead in his home.

“Justice was served, because he can’t hurt nobody else,” Walker now says. “It was like a weight was lifted off my shoulders.”

VII. What next?

Sarah Gallant’s life spiralled into a living hell after Big Bite Pizza.

She became heavily dependent on cocaine and morphine, and found herself in a series of abusive relationships.

An already tangled life turned disastrous when she began injecting drugs. Then came the overdoses — nine or 10 in a short period of time.

She would awake from a comatose state not knowing who she was or how to speak, surrounded by blurry faces while kicking, scratching and clawing at anyone who tried to help her.

“I guess with everything that had happened to me in the past, the first thing I would think about was that I was being raped.”

Gallant would spend much of the time between overdoses at the Recovery Centre, a seven-day detox facility in St. John’s.

Her life hung in the balance for a year as she waited for her turn — either to die, or get into rehab.

“I was calling [the rehab centre], telling them I was going to die before I could get in there,” she said. “It was the most difficult thing I think I have ever had to do in my life. I wanted to get clean so bad but I had no idea how.”

Somewhere in the fray, she had a child — a little boy — who was taken away from her until she could get a grip on her drug addiction.

Gallant says she did not receive any professional help after Shablak was arrested.

“There was no counselling. No programs offered. We were just left in whatever situation we were in in the beginning,” she said.

“It makes you feel like nobody cares about you and you’re not worth anything. For a long time I felt like I was worthless.”

After finally getting a stint in rehab and leaning on support groups like Narcotics Anonymous, Gallant got clean four years ago. She built a strong relationship with her father, who became a source of stability and encouragement in her life.

She was accepted to Memorial University, where she started studying towards a psychology degree.

Just three months into her sobriety, however, she wound up relapsing on a 14-hour binge and consuming a half-ounce of cocaine.

She suffered a heart attack and ended up in the hospital.

“I couldn’t believe I had relapsed,” she said. “I was so close to death. I’m surprised I made it. When I got clean, I knew that if I relapsed, I was going to die.”

Today, she plays the role of supermom, loving partner and dean’s list student. She is one semester shy of her degree, with plans to work towards a master’s degree and a PhD, so she can become the help she never received when she was so desperate for someone to save her.

She lives her life looking forward as much as possible and pushing away all regrets.

“I wouldn’t change what happened to me, because it made me who I am today,” she said. “If I can help one other person, then everything I went through would be worth it.”

Phoebe Walker became a mom, too, shortly after coming home from rehab in 2008.

Even though she was clean, life was still an uphill battle.

In a city of 110,000 people, she struggled to escape finger-pointing and whispers every time she went out in public.

She remembers a sunny day in Bowring Park with her daughter, when a former john approached her and asked for sex.

“I’m there with my child, trying to move forward, trying to be a normal person,” she said. “But the lifestyle still haunts you.”

'You get tired of the nightmares and the flashbacks and you want it all to stop'

Thinking back on those experiences, she shakes with rage.

“As a child, you can’t consent to anything I went through. It wasn’t my fault. I didn’t ask for any of this. I wanted to become a vet and save the animals. Since then, I haven’t even finished high school.”

She escaped the stares of strangers by moving to a community of about 500 people disconnected from the characters of her past.

Walker struggles to hold a job now. She is rocked by post-traumatic stress disorder and crippling anxiety. She has a hard time leaving her house. She tends to a small flock of chickens and her two dogs, and sees her daughter when she can.

She dreams of someday owning a farm and having other victims of childhood trauma come to relax and find peace — like she did at Ranch Ehrlo.

When the winter comes, she moves her bed into the living room and sleeps next to the woodstove.

But she never complains about the weather. It’s the cold and dark inside her that bothers her most — a feeling she’s tried to eradicate with several suicide attempts.

“You get tired of the nightmares and the flashbacks and you want it all to stop,” she said.

“A lot of times I used to just cut, just to feel the pain and see my own blood and know I was an actual person and not this ice cold skeleton I feel like.”

VIII. Trying to speak

Gallant and Walker reconnected several years ago and became friends again. Through their conversations, they decided to face their past head on.

The first step was an assignment for one of Gallant’s psychology classes, where she interviewed Walker and shared her story with the class. It was painful and nerve-wracking, but it was liberating.

After that, they decided to go public.

On Nov. 16, 2016, Walker sent a message to CBC Newfoundland and Labrador’s Facebook page, asking for somebody to speak with.

Two days later, a reporter travelled to meet her. She stated conditions for telling her story — she wanted her real name published and her face front and centre. She wanted to get it all out there, so people wouldn’t whisper behind her back anymore.

There was a problem, however.

Victims of sexual crimes are always protected by a publication ban — their identities can never be revealed.

A year-long process started in the days following that first meeting, which ended with a judge upholding the publication ban. Even though these women wanted to tell their story with their true identities, they were not allowed.

“Why can’t I tell my story?” Gallant repeatedly asked during the phone call when she learned the fate of the court case.

A decision was made to forge ahead anyway — so people could know the true story of what happened to two vulnerable children and the men who preyed on them.

One of those men is dead.

Another walks free, somewhere out there.

All the while, two young women are trying to survive, raise children and help others.

Phoebe Walker has now endured her second winter without electricity.

But she’s alive.

“I’ve had many [suicide] attempts, but I’m still here and I believe it’s to get my story out,” she said.

“I don’t want to be the girl who hides in the shadow of her past. I want to be the survivor who stands up and faces her past.”

Editor's note: Some of the images in this story have been digitally altered to prevent identification of individuals.