January 26, 2019

Tommy Bird is three metres in the air, his legs dangerously close to doing the splits as they grip onto two slim birch tree branches.

“Are you sure that tree’s gonna hold you?” Daniel Tsannie says with a playful laugh.

Bird is spry and energetic for his 58 years, but still needed to embed an axe into the birch and grip his nephew-in-law’s hand for balance to climb the tree.

It shakes, smaller branches break beneath Bird, and he lets out a “Holeh!”

“He’ll do anything to be famous,” Tsannie says, descending into giggles at the scene before him.

“Now you know why men die young, eh,” Bird throws back at him, but he makes it back to the ground without injury.

On this December day, Bird uses an axe to gently hack at what looks like a large black blemish protruding from one of the birch trees that dots the shoreline of a small lake near Southend, Sask.

He chops off chunks of the protrusion as Tsannie stands below holding a plastic bag to catch as many of the falling pieces as he can. He bends over to gather any rogue bits, no matter how small. It’s precious cargo.

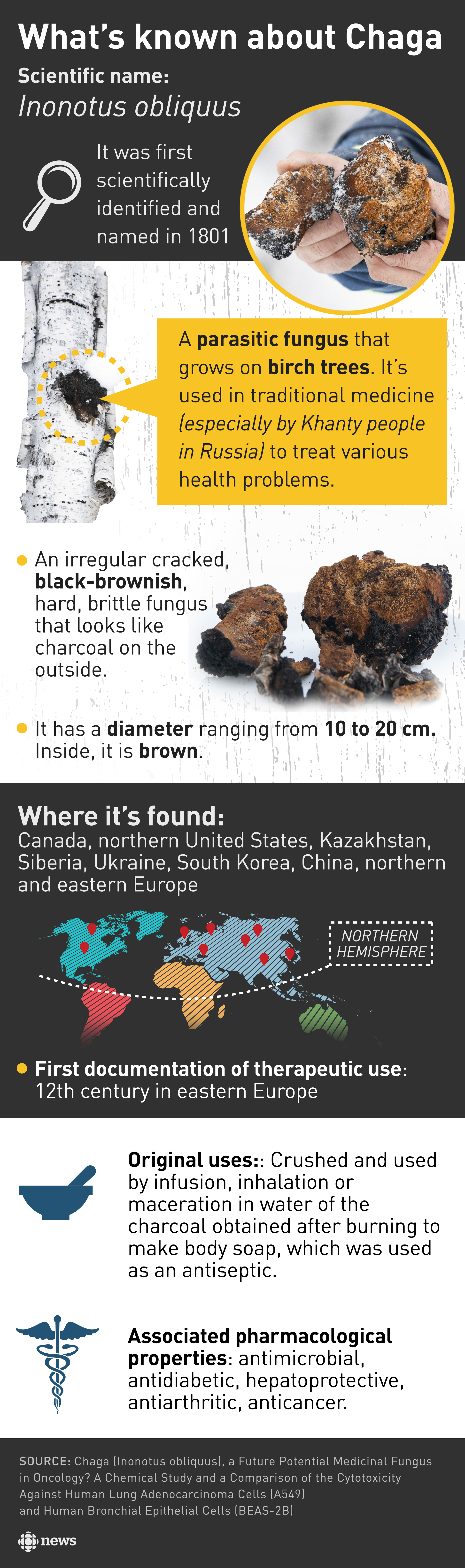

They’ve gathered about two kilograms of what’s called chaga, a type of mushroom that grows on birch trees and doesn’t look like a mushroom at all. The charcoal-like exterior masks a stunning burnt orange colour on the inside. In the north, they call it “good medicine,” and in Cree regions like this one, they call it pōsākan.

Chaga has been gathered for generations by First Nations medicine people. These days, it has become trendy, with chaga offerings popping up in health-conscious markets across Canada. Now, some in the north are struggling with the cultural and environmental implications of it becoming mainstream for people to consume the mushroom.

It's a busy week in Southend, and Bird is antsy to get back to grab a massive shipment of meat that will feed his sled dogs all winter. He hops onto his snowmobile and roars across the small frozen lake until he hits a narrow, hilly path.

He’s surrounded by pine trees that jut out of the rocky landscape. Bird can look at the trees, and based on where they’re weathered, find his direction. The trees, the islands and the hills are all landmarks in a mental map that he’s been building his whole life. He’s put on more than a million kilometres on this land — by foot, dogsled, boat, truck and snowmobile.

Despite Bird’s lifelong propensity for traditional practices, he only started gathering chaga in the past five or six years. Back then, one of his wife's friends started gathering it to help her manage her diabetes. When Bird found out about chaga, it sparked a memory of when he was a child, tagging along as his mother and her sister harvested mushrooms.

He started making dedicated chaga gathering trips with his wife, Marion Bird. Now whenever he’s out trapping or hunting he’s on the lookout for chaga. He gathers about 45 kilograms a year and gives it to anyone in the area who wants it, elders in particular.

Chaga is considered a traditional medicine in Southend. The small number of local herb gatherers share their knowledge of chaga selectively, Marion says. Several elders declined to speak with CBC News.

Tommy’s mother was a traditional medicine gatherer. She was in poor health in December and died the following month. In the years before her death, she passed her knowledge about herbs onto her daughter and to Tsannie.

There are a lot of beliefs around giving tobacco, or another type of gift, in return for harvesting chaga. Tommy follows a practice elders have advised: giving prayer and thanking the Creator for giving him the medicine.

“In my belief (chaga was) given to us for a purpose,” he says.

Tommy Bird recounts the folklore behind the origins of the chaga mushroom. (CBC Graphics)

While Tommy describes Southend as “a whole different world” from urban Canada, his own practice of chaga harvesting started around the same time websites began popping up praising it as an all-natural super-food, thanks in large part to the 2012 release of a book by David Wolfe called Chaga: King of the Medicinal Mushrooms.

With that, came commodification.

These days, Instagram ads about chaga tea are increasingly common. Shops in urban centres across Canada sell blended chaga tea called “elixirs.” Dried up chaga that has been ground into powder sells for around $19 for 100 grams, and store owners say research supports that chaga can bring the pigment back to hair. Chaga extracts are sold online, advising people to put 24 drops under their tongue a day. The Globe and Mail predicts it will be a “hot health food in 2019.”

Tommy is a businessman. He isn’t one to criticize how people make money, but he has never sold chaga. Diplomatically, he says buying chaga might be the way for people who can’t go into the bush every day to access it.

“But we live in a different little community so do we do it differently,” he says.

At least one business around La Ronge, Sask., a three-hour drive south, has started selling chaga, says Eleanor Hegland, an elder and educator in the region.

She has been gathering chaga for three decades and is opposed to selling it.

“It’s just against my culture and it really hurts me. It's OK to pick what you need and to share a little bit but to go selling it, that's against my teachings,” she says.

Hegland is worried about over-harvesting.

“In the future, it’s coming. It’s scary,” she says.

“It’s a greed thing. People look at something to make money off and we have to look at the planet. We can totally destroy the planet.”

It’s a valid concern, says University of Northern British Columbia mycologist Hugues Massicotte. He has spent the past few years delving into the possible medicinal properties of more than 100 different mushrooms gathered in the wild.

A chaga seller who gathers a hundred kilograms of chaga a year in the Northwest Territories was approached by a consortium with a request to provide them with a ton a week, Massicotte says.

That’s unsustainable. Chaga is a parasitic fungus that takes decades to grow on a birch tree.

“We can’t really grow that mushroom at all,” Massicotte says. “It might take several decades before you replenish a landscape with chaga. So once we’re done harvesting this time around we’ll be done.”

Bird is more comfortable outdoors than in, but he and his wife provide a welcoming home for the younger generations of their family. They built a confectionery about 35 years ago as an addition to their house. It's become a gathering place for people in the community.

With the kids and grandkids that live with them shipped off to school, Marion is in the kitchen getting ready to prepare chaga tea. She has come up with her own simple method.

She’s already broken apart the chaga into palm-sized chunks that she stores and freezes in plastic Chinese food containers that her and Tommy save after they get takeout.

Marion puts about five large chunks into a stainless steel pot and brings it to a boil until it turns a deep reddish-caramel colour. When it cools down, she pours it into a jar.

The resulting tea has a slight bitter wooden taste but is mostly flavourless.

The chunks will be re-frozen and re-steeped about six more times over the course of a month, breaking the chaga up into smaller pieces after the third boil to release more of the medicine contained in the mushroom before it’s all used up.

Marion drinks chaga tea every day. Tommy, on the other hand, drinks it once every few weeks whenever his muscles start cramping up after a long day dog sledding or trapping. He thinks drinking it every day is too often, and reduces its health benefits.

Massicotte’s colleague Chow Lee, a biochemistry and molecular biology professor, agrees.

Of the 100-plus mushrooms Lee's team has tested, he says chaga has proven to be by far the most potent anti-inflammatory.

“Inflammation can cause many diseases in addition to causing cancer, so having chaga tea every now and then would actually help in preventing chronic inflammation, therefore preventing chronic illnesses,” Chow says.

Massicotte says a recent study out of France is the first real scientific study done that tries to characterize the medicinal properties of chaga.

While science is at least a generation away from testing mushrooms on humans to prove any cancer-curing claims, chaga has at the very least been found to have an “incredible” amount of antioxidants, Massicotte says.

“That seems to lend some credence to some of the great mythical or legendary properties that the brew seems to have,” he says.

Tommy is bringing his family’s knowledge about chaga into what he calls a fast-paced, high-tech world by hopping onto Facebook and sharing pictures and videos while he gathers it.

A few years ago, it briefly earned him the playful nickname “chaga king,” but he’s also gained criticism for sharing so publicly.

Tsannie defends what Tommy’s doing.

“If you know about chaga, you could share how you get it. If you have kids, show them and let it run through the family. Don't let the tradition die off, our native ways,” Tsannie says.

Tsannie thinks Tommy continues to gather with him because he wants Tsannie to learn and pass on the tradition to his kids. It’s working. Earlier in December, Tsannie took his eight-year-old son out trapping and showed him the ropes of chaga gathering.

Tommy knows that what happens with chaga elsewhere in the world is totally out of his control. For his part, he will continue looking out for chaga every time he’s out in the bush.

It’s part of the good medicine he was given by his ancestors.