May 6, 2020

Note: This story contains details that some may find upsetting.

Hiep Bui spent 23 years at the Cargill meat-packing plant in southern Alberta — picking out bones from ground beef in a refrigerated room.

The 67-year-old was one of around 2,000 workers at the plant, located near the town of High River, south of Calgary.

The plant is the site of the largest COVID-19 outbreak linked to a single facility in North America, according to outbreak data from Canadian and U.S. health authorities. A total of 1,560 cases have been linked to the plant, provincial health officials say, with 949 employees testing positive and two deaths — Bui was the first.

The second was Armando Sallegue, who died of COVID-19 on Tuesday. Sallegue's son, Arwyn, worked at the plant and was confirmed to have the virus the same day his father began to show symptoms.

The deaths, and the coronavirus outbreak, put into sharp relief the heavy toll meat-packing work can take on members of a workforce that often have few other opportunities.

"The union asked for help, the workers asked for help. The workplace was declared safe ... and a worker has died," said Alex Shevalier, president of the Calgary and District Labour Council, during an online vigil for workers who have lost their lives on the job.

"What we do now is what matters. We cannot bring that sister back but we have to fight for the living. We need a public inquiry and we need a criminal investigation and we need them now.”

On Monday, the same day the Cargill plant reopened after a two-week closure, Bui’s memorial service was livestreamed on social media.

Bui’s husband of more than 25 years, Nga Nguyen — who also works at Cargill and contracted COVID-19 — was asked whether Cargill had called him to express its condolences.

Nguyen shrugged and shook his head. Communicating in Vietnamese through an interpreter, he said, no, the company hadn’t called.

“He’s feeling numb,” his interpreter said. “He doesn’t know if he’s angry. Just numb.”

Cargill, a company worth billions, has been accused by employees and the union of caring more about its bottom line than worker wellbeing.

"Honestly speaking, they don't care about their employees," one worker said. "They're saying they can replace people at any time. They don't care."

John Keating, president of Cargill Meat Solutions, a subsidiary of Cargill, said the company puts people first. He said his heart hurts to lose an employee, and he was surprised to hear the company has yet to reach out to Bui's husband.

He said the company was “hit overnight” by the outbreak and there are lessons to be learned.

“If we need to feel the need to apologize, absolutely, we will apologize. We're a very humble organization, we feel bad about what happened but at the same time we're very confident in how we run our businesses, how we run our processes.”

On Tuesday, the day after CBC News spoke to Keating, the company said it had reached out to Nguyen to offer condolences.

After employees first began to test positive for the coronavirus, some told CBC News they continued to work in close quarters with colleagues despite physical distancing measures put in place by the company and said Cargill pressured them to return to work even after they contracted COVID-19.

The number of cases at Cargill is staggering even when compared with the U.S., which has the highest total number of active COVID-19 cases and deaths in the world. As of May 1, there were 4,913 COVID-19 cases in total among all meat-packing plants in the U.S., according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

CBC News interviewed 14 current employees of Cargill for this story. Their identities have been kept confidential because they fear negative impacts on their employment should they be identified.

The workers at the plant are primarily immigrants to Canada or temporary foreign workers and many speak limited to no English. Some say their job security is key to them remaining in the country.

Employees have said they’ve sustained injuries at the plant, from blackened fingers to knee damage that has made it difficult to walk.

Cargill said ergonomic experts were in place at the facility to guide the work.

"We have a ramp-up plan in place to ensure our team builds strength and protects their long-term health. We are focused on keeping our employees safe and healthy now and for the future," company spokesperson Daniel Sullivan said in an email.

The 'kill floor'

The first thing employees say you notice when you enter the Cargill facility in High River is the smell — something familiar, like that of an animal, but with a distinctive note of blood hanging in the air.

There are two main areas of Cargill’s facility. On the harvest floor, colloquially dubbed the "kill floor," workers bleed cattle, skin them and hang them from hooks in a warm environment.

The majority of the area on the kill floor is more spaced out, allowing for two metres of space between employees in most areas. But the work can still be challenging, employees say.

Cattle are led into what’s known as the knocking area, where they are hit in the head with a bolt gun meant to stun them. Then, using a knife, a worker will cut the throat of the animal to bleed it.

This work can be dangerous for employees, as the behaviour of a nervous animal is difficult to predict.

Then there's the fabrication line, where workers say they're packed in elbow to elbow. Here, they work cutting meat for eight hours a day, often using knives to trim carcasses and remove fat.

Workers say part of the challenge of working on the fabrication line is the speed with which it moves — rates of speed which they say have led to injuries.

"My fingernail is all black. Not only me, all the employees," said one worker on the fabrication line, "because there’s no blood circulation, because of too much grip. You need to hurry and then your hand is numb.

"Some of my [fellow] employees, not only one, two, three fingers, all black."

WATCH | Video captured by a Cargill worker shows crowded conditions in a changing room at the plant prior to its temporary closure:

Another employee who works in maintenance at the facility said those on the line feel constant pressure to keep their speed up. Delays, such as mechanical issues, can exacerbate those stressors.

"Some machines are just worn out [and will fail]. Then, it’s constant screaming, cursing ... and I mean, people are getting frustrated with that," he said.

"But some of these people are new in Canada, they’re from the Philippines. So basically, they get scared, they think they’re going to be sent back home or they’ll lose their permanent residence. So they basically just shut up and do what they’re being told."

These workers, completing repetitive tasks over and over all day, are particularly at risk of developing musculoskeletal disorders like carpal tunnel syndrome, tendonitis and muscle strain, said Jessica Leibler, an environmental health professor from Boston University.

'I cannot walk'

One worker said a fellow employee cut off three of his fingers while slicing meat on a weekend shift and began to bleed.

"He was bleeding for 40 minutes because they don’t want us to call 911," he said. "They wanted us to call the on-call nurse because she will evaluate the guy, whether he needs to go to hospital."

Sullivan, the Cargill spokesperson, said employees with concerns should report it through the "many reporting channels" open to them.

"To our knowledge, this [incident] is false. Our policy is to contact medical professionals or our nursing staff when an injury occurs," Sullivan said in an email.

Injuries have also occurred in other areas. One worker in the packaging area of the facility said she damaged her knee repeatedly lifting heavy boxes.

"Now, I cannot even stand too long, I cannot walk," she said.

The cramped facilities mean breaks are just as crowded as regular shifts, employees said.

Without fail, one worker said, coffee breaks and lunchtime see the cafeteria — referred to as the "feedlot" — fill to capacity with employees.

When employees are done eating, they’ll move into the locker-room, chatting and lounging while they wait to be let back onto the main floor.

"In the locker-room, it’s super-crowded," one employee said. "Very filthy."

A 'clear danger'

Concerns for workers' well-being extend beyond their physical health.

Leibler said although meat-processing workers experience some of the highest rates of occupational injury for all types of injuries, there have been very few studies of workers’ mental health.

She has studied workers at a U.S. meat-packing plant and found they experienced higher levels of serious psychological distress than those in the general population.

"They open themselves up, working in these environments, to laceration injury, to repetitive injury, to musculoskeletal injury in addition to the mental health stress," she said.

"There is clear danger in working in these environments, but many of the people who work in them appreciate the income. Many of them are immigrants, many of them are supporting families. And so it’s a cost-benefit analysis for them, I think, even on a daily basis."

The bloody and often depressing nature of the work often means many employees burn out quickly, one employee working on the kill floor said.

"It’s hard to do this every day. Especially when the cow, when they knock it, it makes a voice. Like it’s screaming or something like that," he said. "If people are emotional, it’s hard for them to keep that job."

Other studies have found workers in meat-packing plants face intense psychological pressure and sometimes a disconnect in empathy because of their work environments.

Leibler also said her research may underestimate the mental health impacts among workers — as more mentally or physically robust workers are likely to remain in the job and those who have experienced a major injury (mental or physical) might be less likely to participate in research.

"I think fundamentally the industrial slaughterhouse model is not sustainable," she said.

"The system is optimized for maximal output but with much less concern for the experience of the workers throughout the process.”

Leibler said the more immediate challenge faced by meat-packing corporations is to show they value workers by allowing them to stay home with pay while sick or if they are possibly infectious.

On Monday, Cargill’s High River plant reopened — two weeks and a day after Bui’s death from COVID-19.

United Food and Commercial Workers Local 401, the union that represents workers at the plant, had requested a stop-work order and filed an unfair labour practice complaint against the plant and the provincial government in hope of preventing the reopening. It has also called for a criminal investigation.

The plant asked all employees who are eligible to return to work in the harvest department to report for their shifts.

Days before the reopening, the union surveyed more than 600 workers in four languages; 85 per cent said they were afraid to return to work.

Ricardo Morales, director of community development and integration services with the Calgary Catholic Immigration Society, has been leading a team to support workers at the plant.

They’ve been translating health and safety information into Oromo, Tagalog, Spanish, Vietnamese and Chinese for workers.

"I think Cargill probably could have done a better job communicating with employees as to what support they could receive from the company," he said.

WATCH | Workers worry about safety as Cargill plant reopens:

Immigrants in Canada have more concerns about their health and financial security during the COVID-19 pandemic than the Canadian population as a whole, according to the results of a recent survey from Statistics Canada, and Morales said he’s seen evidence of that on the ground with Cargill workers.

"You are just not dealing with an ordinary situation. You need to look at ways, culturally, how are people responding and how are people coping under these circumstances."

Morales said while the community has banded together, Cargill workers still face intense stressors over their immigration status and food security — with some quarantining workers unsure where their next meal will come from.

Revenue in the billions

Cargill Ltd. is a Canadian subsidiary of the U.S.-based Cargill, which reported revenue of $113.5 billion US and net earnings of $2.56 billion last year.

The company is the largest private company in the U.S. in terms of revenue, and the Cargills, a family of reclusive billionaires, still own more than 90 per cent of the corporation.

Cargill's High River plant opened in 1989 with an initial slaughter capacity of 1,200 head of cattle per day, eventually growing to become the largest beef processing facility in Canada, processing 4,500 head a day.

Before opening, news reports at the time show some critics worried the company was buying its way into a market already suffering from overcapacity and would lead to the closures of other plants.

The plant — which was not unionized at the time and paid its employees less per hour than other Alberta plants — did, in fact, lower production costs and plants around the province began to close.

Today, the Cargill plant, which has since been unionized, provides around 40 per cent of all beef processing in Canada.

Wages at the Cargill plant start at $17.95 per hour, according to the collective agreement.

Cargill has said that as an essential part of Canada’s food supply chain, it is committed to continuing production.

‘That’s only flu … you’re fit to work’

To stay open at this time, the company said it has implemented measures to keep employees safe.

It has installed protective barriers on the production floor to allow for more spacing between employees and introduced face shields where that wasn’t possible.

Cargill also said it hoped to reduce carpooling by workers through utilizing buses with protective barriers between the seats. Many of the employees live in large households and share transportation.

But some employees feel other actions by the company increased their risk, like offering bonuses during the COVID-19 outbreak. Workers worried that by missing work, they would miss out on the bonus.

Some say the company continued to try to lure them back to work from self-isolation as the plant prepared to reopen on May 4.

"They called my husband, the [Cargill] nurse called, but he still has symptoms," one worker said of her husband, who is also an employee. "They said, ‘That’s only flu, that’s only cough. You’re fit to work.’"

In an email, Cargill spokesperson Daniel Sullivan said the company had been "very clear" in communications to employees that they should not come to work sick or if they have had contact with someone with COVID-19 in the past 14 days.

"Employees who must remain off work due to COVID-19 impacts have access to up to 80 hours of paid leave and short-term disability benefits are available to eligible employees," the company said.

After the COVID-19 pandemic was declared, CBC News reported that no preventative or in-person inspection of the Cargill plant was done.

A live video inspection by Alberta Occupational Health and Safety (OHS), conducted after dozens at the plant were already sick with COVID-19, concluded the work site was safe to remain open. The inspection didn’t include the harvest or kill floor because slaughter activities weren’t taking place that day.

OHS is now investigating and provincial health officials were in attendance for the reopening.

Other slaughterhouse outbreaks

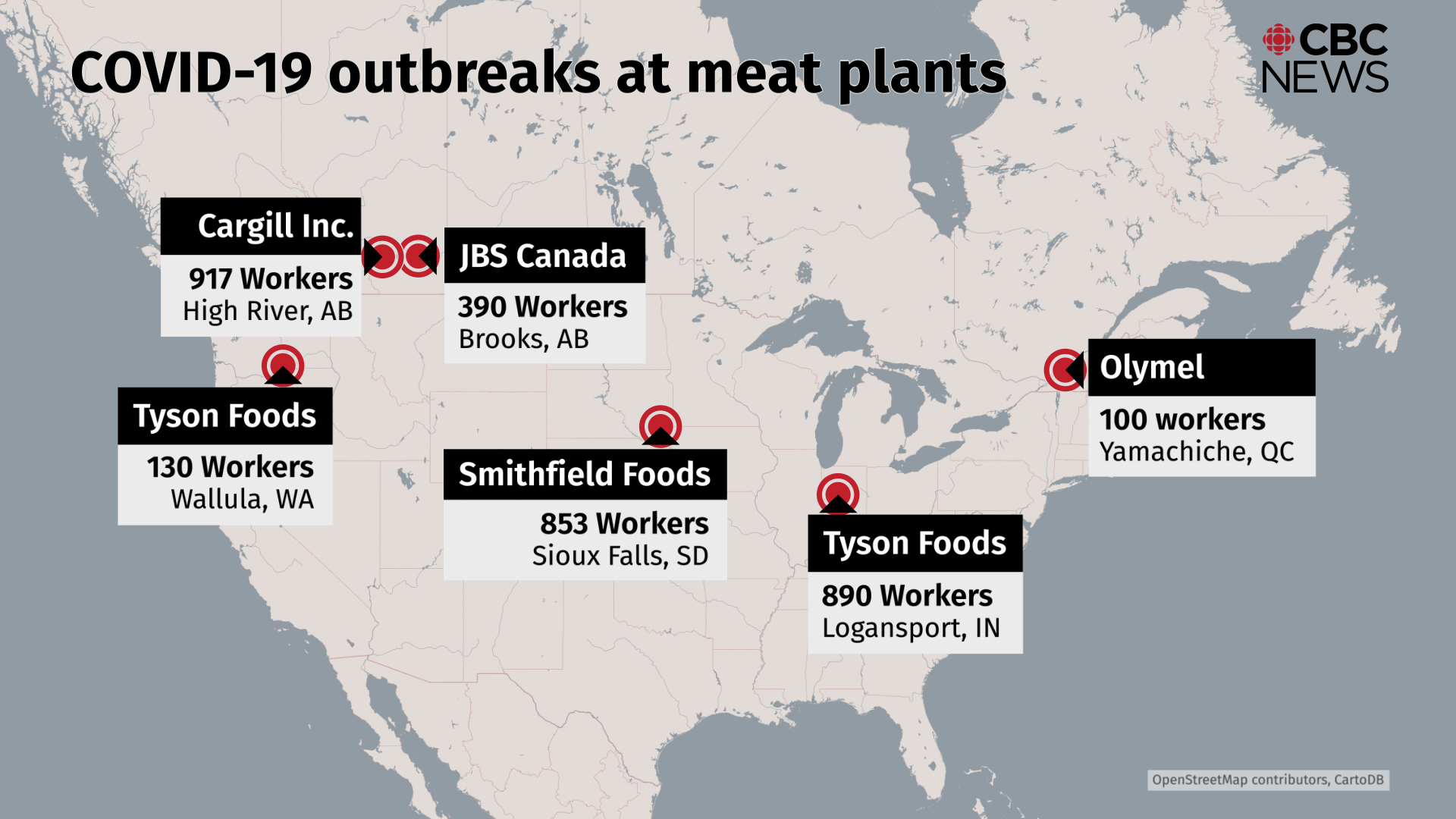

While Cargill is the site of the largest outbreak, it’s far from alone — meat-packing facilities across North America are hotspots for coronavirus.

Alberta’s second-largest outbreak, where at least 487 workers have tested positive as of Tuesday, is at the JBS Canada beef plant in the southeastern city of Brooks. That plant remains open.

Meat-processing plants in Quebec, Ontario and B.C., and two dozen across the U.S. have had to temporarily suspend operations because of smaller outbreaks. In the U.S., 20 meat-processing workers have died because of COVID-19, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

There have been similar allegations of unsafe practices, like those workers have made at the Cargill plant, reported at multiple facilities.

The outbreak at Cargill has spread into the greater community. Cases among staff at a High River retirement facility and on a nearby First Nation have been traced back to the plant.

Leibler, the environmental health professor, said the outbreaks have hopefully shone some light on the undervalued role of meat-processing workers and the profit-maximizing environment in which food is produced.

"I think in a lot of developed countries, the process as to how we produce the meat that we buy in our supermarket is very much like a black box. People don’t think about it," she said.

"Hopefully it’s beneficial for all of us to learn a little bit more about this workforce in this terrible context."

Another worker on the kill floor said his job at Cargill has its pluses, like working with and developing relationships with people from all over the world.

But after the company’s response to the COVID-19 outbreak, he said he feels betrayed.

"They ignored it even after employees spoke out," he said. "They don’t care about the [workers]. They care about the profit."