July 7, 2020

Stand atop Mount Erickson in southeastern British Columbia and it feels like you can see forever.

Look north, and peer along the jagged ridgelines of the High Rock Range, which stretch to the horizon. To the south, snow-capped peaks in the Crowsnest Range cut into the blue sky, rising above dense green forests. Across the valley to the west, row upon row of sawtoothed summits fade into the distance, melding into mesmerizing array.

And then you look down.

Down the austere slope, in the valley below, is a massive, open-pit coal mine.

The word “mine” evokes images of soot-smeared workers in underground tunnels, but this is actually a mountain in the process of being deconstructed. A geologic wound. Its slopes are blackened and tiered, abuzz with enormous yellow trucks that look tiny from this distance, kicking up grey plumes of dust as they haul the pulverized mountain away, load by load.

This is one of five coal mines owned by Teck Resources in B.C’s Elk Valley. Together, these operations produce the bulk of the mining revenue in a province that has made coal its top export.

Now, turn on your heel and look to the east: past the Continental Divide, over the invisible border into Alberta’s Crowsnest Pass. There’s the distinctive, rounded peak of Crowsnest Mountain and, just beyond that, the Livingstone Range. The same, high-quality coal is locked away in these mountains, yet there are no operational mines here. The last one closed in 1983.

The difference dates back to 1976. That’s when the Progressive Conservative government of premier Peter Lougheed adopted its Coal Development Policy, which restricted open-pit mines across most of the province's Rocky Mountains and Foothills. For the last 44 years, this policy protected some of Alberta's most pristine and iconic landscapes. It also chased mining companies into neighbouring B.C., limiting potential livelihoods for thousands of Albertans.

Now, this long-standing tradeoff between environmental protection and economic opportunity is poised to change.

On June 1, the United Conservative government of Premier Jason Kenney rescinded the coal policy. The full implications of this are not yet clear, but there is growing tension — both nervous and excited energy — about what it will bring.

What is known is that the change happened suddenly, with virtually no public consultation but plenty of behind-the-scenes lobbying. And it didn’t happen in isolation. It came alongside a rapid-fire series of legislative changes that removed hurdles for industrial development, more broadly, during a particularly desperate economic moment.

Alberta has been struggling with persistent unemployment since the oil-price crash of 2015. Then COVID-19 hit, prompting warnings that joblessness could reach 25 per cent and the provincial deficit could balloon to $20 billion. Albertans are used to booms and busts, but are now grappling with the realization that the oil industry may have seen its last boom. This has only dialled up tensions in the perennial struggle between protecting nature and putting it to use.

Some residents of former mining towns in southwestern Alberta applaud the prospect of coal coming back, bringing high-paying jobs to a low-earning part of the province. Others worry about mountains being blasted apart near their backyards, throwing black dust into the air and toxic minerals into the water. And what’s playing out here is likely just a preview.

The next conflict over coal may come further north, in Bighorn Country. Just a couple of years ago, this part of central Alberta had been slated to become a new provincial park. Now it has seen some of the most stringent protections of the 1976 policy removed, opening the door for vast expanses of coal lease agreements to be turned into mines.

Even further north, near Hinton and Grande Cache, lies the only area where coal mines currently operate in Alberta’s mountains. The industry has been a boon, at times, leading new towns to spring from the ground up. But the caprice of the market has also seen towns abandoned or, as recently as 2018, dissolved.

At stake in all this is the land that has long defined this province and its people.

The Rockies, the Foothills, the Prairies.

These places are sacred to the Indigenous people whose ancestors first roamed them. They were the motivation for settlers to come West. The shimmering wheat fields, rolling hills and snowy peaks are emblems that adorn Alberta’s coat of arms and its provincial flag. They are fundamental to how we see ourselves and how we present ourselves to the world. The various uses to which we have put the land, the way we have treated it, the joys we find in it, and the energy-rich treasures we have found under it have shaped our history, economy and society.

Living in Alberta is a complicated balance of honouring the land, exploiting the land, protecting the land.

'We were born from coal'

The earliest written record of coal in the lands that would become Alberta comes from 1793. That’s when Peter Fidler, a British surveyor with the Hudson’s Bay Company, noticed a seam of coal near the Red Deer River and recognized its quality.

“I brought some of this [coal] & put on the tent fire, which burnt very well without any crackling noise,” he wrote in his journal.

In 1874, an entrepreneur from New York City opened the first commercial coal mine on the banks of the Oldman River. The Blackfoot name for this land was Sik-ooh-kotoki or “place of the black rocks.” A larger mine opened in 1882 and the Town of Coalbanks was formed. It was later renamed Lethbridge. The names of nearby towns still speak to this history: Coaldale, Coalhurst, Black Diamond.

Drawn by the vast coal deposits in the area, Canadian Pacific Rail built its main line from Lethbridge westward through the Crowsnest Pass in 1897 and 1898. The town of Coleman was established in 1903 by the International Coal and Coke Company, the first of many “company towns” to come.

The growing transportation network, along with economic opportunity and inexpensive land, drew immigrants by the tens of thousands. Alberta, as we know it, was born.

Alberta’s fortunes have always been tied to natural resources and, with the gusher at Leduc in 1947, oil came to dominate. But coal carried on.

By 1975, according to historical records maintained by the Alberta Energy Regulator, a total of 2,342 mining projects had been undertaken in the province. About a third of these were small, exploratory projects that failed to produce any coal at all. Another tenth managed to haul only a tiny amount out of the ground. The rest — about 1,200 projects, in total — varied widely in scale and scope but, on average, produced just over a million tonnes of coal, each, over their lifespans, when you include two that are still in operation today.

By the 1970s, coal was still in demand, but the times were changing. There was a shift in society, with widespread social reforms and calls for environmental protection.

In 1976, Alberta decided the coal industry needed more regulation.

'A restrictive policy'

In its throne speech that year, Lougheed’s government laid out its priorities. They included a vow to restrain public spending, a pledge to reform the criminal justice system and a promise to introduce an overarching "Coal Development Policy for Alberta."

The policy had dual goals of increasing government royalties and protecting sensitive lands.

"No development will be permitted unless the government is satisfied that it may proceed without irreparable harm to the environment," the policy reads. To that end, it established four categories of lands.

Category 1 (in red, below), where all coal development was forbidden, encompassed mostly the Rocky Mountains, spanning roughly 700 kilometres from the U.S. border north to what is now Kakwa Wildland Provincial Park.

Category 2 (in blue), where open-pit mines were off-limits, covered lands mostly to the east, including both mountains and foothills.

Categories 3 (green) and 4 (purple) generally trended further eastward, toward the plains, and saw fewer restrictions.

Some argued the policy would kill coal in Alberta. Headlines from the Lethbridge Herald in 1976 read, “Coal policy threatens profits, new mines” and “Watershed preservation top government priority." Citing “industry sources,” one article said the policy “could destroy Alberta's chances at grabbing a growing export market for coal, and that the province will lose out to British Columbia in the coming coal boom.”

“I think that the industry will consider it a restrictive policy,” energy minister (and later premier) Don Getty admitted in an interview with CBC Radio.

“And I think that if there are provinces more aggressive than this in attempting to attract coal development, you will find that some potential developments will leave our province and go elsewhere, yes.”

CBC Radio news items on The World at Six from June 21, 1976 about Alberta's new Coal Development Policy.

Like the policy, subsequent coal development varied by geography.

Out on the prairies, where the policy didn’t apply, numerous coal projects were approved in the late 1970s and early 1980s. These mines extracted a lower-quality coal and often included adjacent power plants, which helped meet Alberta’s growing electricity demands. With some projects grandfathered in, mining of higher-quality coal — the kind required for making steel — also continued and even expanded in the mountains near Hinton and Grande Cache.

But down in Crowsnest Pass, the industry dwindled under the policy’s yoke. A proposed project just north of Blairmore at Grassy Mountain, which had already been partially mined between 1913 and 1958, was shelved and later abandoned. Existing mines shut down. The community that coal built hasn’t seen an active operation for the past 37 years.

The industry may have vanished in the province’s southwest, but when you add up all the mining across Alberta today, it still rivals that of B.C. Together, the two provinces account for roughly 85 per cent of Canada’s total coal production, but they mine coal for different purposes. While Alberta still relies heavily on coal for power generation, B.C. doesn’t burn it for electricity.

Rather, B.C. ships vast quantities of coal overseas, largely the steel-making variety. At roughly $6.7 billion, B.C.’s total coal exports last year were 20 times greater than Alberta’s.

But Alberta is weaning itself off coal as a power source. Generating stations are being converted to burn natural gas and the province is on track to completely phase out coal-fired electricity by 2030. So, if there’s any future for the coal industry in this province, it’s in those same international markets.

Which brings us back to Crowsnest Pass, where some residents look at the bustling mines just over the provincial border and wonder: Why not here?

“It’s difficult to look west and see the thriving communities of Sparwood, Elkford and Fernie, all flourishing because of the active coal mines surrounding their communities,” Crowsnest Pass Mayor Blair Painter wrote in a letter of support for a new mining project at Grassy Mountain.

“In order to prosper, this community is in desperate need of industry… Why not the industry that is literally in our backyards? We were born from coal in the ground and we can again prosper through this resource.”

The mayor wrote that letter in January 2019 hoping a single coal project, one that sits on a rare section of less-restricted Category 4 land in the Rockies, would go ahead.

A few months later, the political ground would shift, and the industry’s prospects along with it.

Digging into the coal lobby

When asked why the coal policy was unceremoniously rescinded by the current government, some critics, including the previous NDP environment minister Shannon Phillips, are quick with an answer: lobbying.

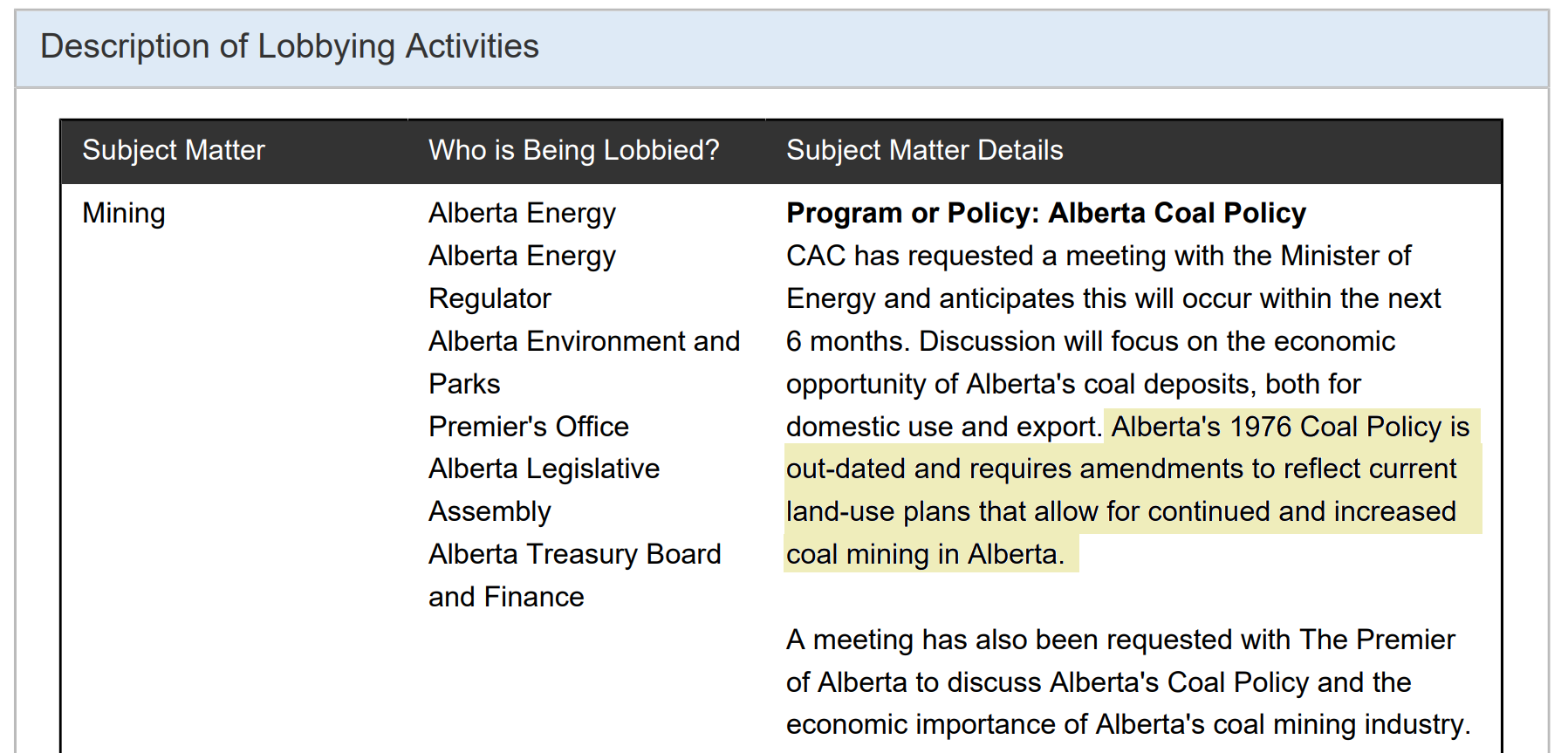

The filings in Alberta's lobbyist registry offer a glimpse into what went down in the halls of power, and how it changed over time.

The online registry dates back to 2017 and a reading of all records that mention "coal" reveals a noticeable uptick in access for the Coal Association of Canada after the election of the United Conservative Party in the spring of 2019. Prior to that, there are no records of the coal association securing meetings with any cabinet ministers under the NDP government.

Robin Campbell’s name appears often in those documents. After serving as finance minister and environment minister under previous Progressive Conservative governments in Alberta, he’s now head of the coal association.

Just over a month after the UCP won the election, lobbying records show Campbell met with the new environment minister, Jason Nixon, to discuss “economic opportunities for the Province of Alberta as a result of proposed coal mining activity, primarily in the Eastern Slopes [of the Rocky Mountains].”

Three days later, the coal association met with the deputy energy minister to try and amend the 1976 coal policy to encourage development on those eastern slopes. Soon, records show there were meetings with the minister of Indigenous relations to discuss consultation, requests for a meeting with the premier, another get-together with Nixon and with his department, a meeting with the minister of red tape reduction and a presentation to the UCP's energy caucus.

The coal association then met with Energy Minister Sonya Savage by teleconference on April 30 to discuss the coal policy, among other topics. Just over two weeks later, the government announced, via a news release issued the Friday afternoon before the May long weekend, that it would rescind the 44-year-old policy.

Since that release, which trumpeted flexibility for industry, the continued protection of sensitive lands and the arrival of modern oversight to attract new investment, the government has declined interview requests about the coal policy.

In response to inquiries, its spokespeople have pointed to official statements saying all environmental regulations remain in place and the same regulatory processes applied to other industries will now be applied to coal.

But what the government didn’t highlight in its statements, and what it hasn’t discussed since, is the removal of those Category 2 prohibitions against open-pit mining in vast stretches of the Rockies and Foothills.

Requests for interviews with Savage and Nixon, specifically, were rejected. Alberta Energy spokesperson Kavi Bal responded with a reiteration of the government's previous statements, along with a letter of support for the changes from the Piikani Nation in southern Alberta. Asked whether there was any consultation with any other organizations, Bal did not reply.

On June 3, Savage did tweet about the coal policy being rescinded. "We will continue to protect environmentally sensitive and recreational lands along Alberta’s Eastern Slopes while addressing the continued and growing demand for high quality metallurgical coal," she said, referring to the steel-making type of coal found in the mountains.

Campbell, with the Coal Association of Canada, also did not respond to an interview request for this article, but did speak with CBC News shortly after the policy change was announced. At that time, he celebrated the government's new direction, which he said would clear the way for more coal projects in areas where it was previously difficult to mine.

"For example, around Rocky Mountain House, we have a couple of projects that were on Category 2 lands. This now allows them to move forward,” he said. “It allows them to go out and raise money in the international community. And it allows them to start building an operation, which is going to create jobs."

While it was possible in the past for companies to apply for an exemption to the coal policy's restrictions, Campbell said it was cumbersome and rescinding the policy outright would remove a major barrier to investment. He said "at least a half a dozen" companies are currently looking at developing mines on lands where it would have been previously prohibited and "there will be more."

"Coal's not going away,” he said, “as much as some people like to think it is."

II.

Stewards of the land

Drive west along Highway 533 from Nanton, and the flat prairie begins to undulate.

Small rock outcroppings start to dot the rolling hills, hinting at the larger mountains in the distance. Along the barbed wire fences that flank the road, numbered bird houses have been installed at regular intervals, part of a successful effort to coax bluebirds back to the region after a long absence.

Behind the fences, the ranchlands are filled with more than cattle. A mother moose and her two calves glance back at the highway before cresting a hilltop. Around the hillside, 100 cows roam with calves of their own.

This is the Alberta of postcards. It’s also the Alberta of industry.

Turn south along Highway 22, at the entrance to Chain Lakes Provincial Park, and soon you’ll pass the Burton Creek Compressor Station, where massive pipelines rise from the ground so the natural gas that flows through them can be boosted along its journey.

It’s not that this area is free from development, says Kevin Van Tighem, it’s that the man-made and the natural have found a way to co-exist. It’s one part of the province where he thinks Alberta has got it right, managing to mix a variety of land uses without any one interfering too much with any other. But the balance is delicate.

Van Tighem is a former Banff National Park superintendent who now splits his time between Canmore and a home in this part of southwestern Alberta. He finds himself spending more and more time out here.

“How could you not,” he says, gesturing toward the mountains upstream from the steep embankments of the Oldman River, “with all this?”

Van Tighem speaks for residents and business owners in the area who have banded together to form the Livingstone Landowners Group, a grassroots organization advocating for a nuanced approach to local development. Like most of rural Alberta, there’s a conservative bent to the politics out here, but one that is especially rooted in conservation. Van Tighem admits his own politics tend to veer further left than most of his neighbours, but says protecting this land is an issue that cuts across ideological lines.

He says ranchers who have been making a living from this land for generations want that to continue for generations to come. They consider themselves stewards. They don't oppose using the land, but they don’t want it used up.

In the past, the Livingstone Landowners have advocated against what they saw as reckless use of all-terrain vehicles in the area. They have lobbied against the “industrial creep” of expanding transmission lines that connect the growing banks of wind turbines near Pincher Creek to the electrical grid, fragmenting the landscape.

And recently, they have partnered with environmental non-profits Yellowstone to Yukon and the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society to oppose what all three groups see as one of the biggest threats to the harmony of this land: new coal mines.

"The folks down here are not terrifically interested in open-pit mining being right adjacent to where they're trying to make a living by grazing cattle," says Phillips, the former NDP environment minister and current MLA for Lethbridge-West.

Phillips says the South Saskatchewan Regional Plan, a land-use policy that encompasses most of southern Alberta, provides some protection for those who don’t want to see the balance disturbed. She says the plan has its flaws but gets a lot right, too — high praise for a policy conceived by a previous, PC government. She holds her harshest criticism for the current government’s handling of the coal file.

"It's astonishing that this government, this UCP government, thought they could do an end run around that planning and around the communities down here with this rescinding of the coal policy," she says.

Continue south on Highway 22, though, and you’ll reach the Crowsnest Highway. Head west from here, into the pass, the historic heartland of coal, and you’ll find mixed feelings about the potential for a renaissance.

Dusting off the past

For nearly four decades, the coal industry in Crowsnest Pass has been relegated to museum exhibits and abandoned mine shaft tours.

Once the largest coal-producing region in the province, the highway now runs along a flat, sparsely treed plain between mountains where small towns like Bellevue, Blairmore and Coleman are separated by long stretches of land dotted here and there with rusting remnants of the former glory days. Off the main road and up into the mountains, you can find the rubble of abandoned coal towns like Lille, wiped from the map except for the ruins of an old hotel and some crumbling coke ovens.

But this is where the next era of open-pit mining in Alberta could first come to pass.

A number of Australian companies are betting on it, led by Riversdale Resources. Its proposed Grassy Mountain project would pick up where an abandoned coal mine left off decades ago on a 1,500-hectare site just north of Blairmore. This is a small and rare section of Category 4 land right in the heart of the Rockies, so the project was subject to fewer restrictions under the 1976 coal policy.

The company has been seeking federal and provincial approval since 2014 for the project, which it estimates could dig up four-million tonnes of steelmaking coal annually over the 23-year lifespan of the open-pit mine, creating nearly 400 full-time jobs at peak production.

In anticipation of the mine’s approval, Riversdale is already seeking to fill high-level positions in Crowsnest Pass. As of June, it had eight active job postings, including for an HR administrator, a project engineer, a senior mining engineer, and a head of marketing and sales. The sales position comes with an advertised salary of $150,000 to $200,000 plus an annual performance bonus of up to 50 per cent.

This, in a community where the median income is less than $35,000.

Other Australian coal companies have been watching closely, as they ramp up exploration and draw up plans for mines of their own. Companies like Atrum Coal.

“I would say the industry is looking to the success of Riversdale’s project, because it’s the first in the Crowsnest Pass area,” Atrum Coal’s then-CEO Max Wang told the Calgary Herald in 2018.

“There are quite a number of global investors, mostly from Australia, interested in that region … but they are very much looking to the success of Grassy Mountain.”

And now, Atrum is even more interested. In May, it welcomed Alberta’s decision to rescind the 1976 coal policy, saying it represented a significant step forward for the company’s Elan project, which sits on former Category 2 lands, where open-pit mining used to be banned.

The company is hoping to build two mines in the Livingstone Range, just north of Grassy Mountain. Its lease agreements in this area cover an area roughly twice the size of the City of Vancouver.

In central Alberta, meanwhile, Australian-backed Ram River Coal Corporation is considering the feasibility of a mine in the heart of Bighorn Country, with the company completing a technical review of the project in 2017. Its leases, too, are on former Category 2 lands.

But those projects aren't as far along as Grassy Mountain, which just completed the required environmental impact assessment and is set to go to a public hearing later this year. This is the mine on most people's minds in Crowsnest Pass. This area has struggled economically even during Alberta’s oil booms, so it’s not hard to understand why the prospect of a major new employer coming to town has many excited.

The last time census takers came around here, the median income was $34,554, or 19 per cent less than a typical Albertan’s. Today, just seven per cent of the municipality’s property tax base comes from industry, according to Mayor Blair Painter, with the remaining 93 per cent falling on homeowners. He wants to see that balance shift and believes the best chance is a return to the coal-mining roots that created the community more than a century ago.

“We are a poor community,” the mayor wrote in his letter of support for the Grassy Mountain project.

“Most of the residents who earn a decent income in Crowsnest Pass do so by driving to work at the Teck Resources mines across the border. However, secondary incomes are hard to find in this area. Most jobs are at minimum wage and are few and far between.”

One longtime employer is the Bellevue Underground Mine, a historic coal operation that closed in 1961 and later turned into a tourist attraction.

Now, interpretive guides take visitors underground, teaching them about the miners who started digging the sprawling network of tunnels back in 1901. The tour just scratches the surface of that network. Unmaintained tunnels stretch for more than 240 kilometres, in total, beneath Bellevue and the neighbouring community of Frank.

“There really isn’t much of the past here that isn’t on top of mining,” says Brandy Gregory, the historic mine’s general manager. “There are underground mines everywhere. There were actually 16 operational mines at the time, when ours was in existence.”

A resident of Crowsnest Pass for the past 21 years, Gregory says the community is “very quiet” and businesses struggle to stay afloat. Tourism helps, as do the mining jobs a short commute away in B.C., but she’s eager to see the Grassy Mountain project go ahead on the Alberta side of the border and, ideally, more coal mines after that.

“It’s great to actually see the projects coming here instead of going somewhere else,” she says. “All these other communities are growing but we have this teeny-tiny, beautiful little historic community that could be expanding and, instead, it’s being lost because we don’t have the industry or the funding to keep it alive.”

Riversdale, the company behind the Grassy Mountain project, didn't reply to a request for comment. But Gregory says it has been a positive presence in Crowsnest Pass already.

“Riversdale really goes out of their way to support the community,” she says. “They are actually one of our biggest sponsors.”

Ask around town, though, and you’ll find a diversity of opinion. A half dozen residents who preferred not to attach their names to their comments said the community is far from unanimous in support of active coal mining returning to the area. The main concerns are environmental: the potential impact on tourism, water and the landscape.

To see why there’s both excitement and worry in Crowsnest Pass, you just need to drive a little further west, across the B.C. border, and pull over in Sparwood.

The price of prosperity

Coal mining has brought prosperity to this community of roughly 4,000 people in the Elk Valley. The median income here is $44,309, according to the last census, which is 34 per cent higher than that of a typical British Columbian. Men living in Sparwood enjoyed an especially high median income of $88,101.

But the land has paid a price.

“I think the Elk Valley is a great example to see when something goes wrong, there’s no going back,” says Katie Morrison, conservation director with the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Association’s southern Alberta branch.

“The impact can be so great that it’s just not worth the risk for such an important landscape.”

Teck Resources is the major player in the valley, employing thousands of people at its five mines dotting the Elk and Fording rivers. For years, the mines have been leaching selenium into those rivers, setting off disputes with U.S. officials and decimating rare fish populations.

Teck installed a $600-million wastewater treatment facility at one of the mines in an effort to address the problem back in 2014, only for the new facility to unintentionally release nitrite, ammonia, phosphorus and hydrogen sulfide into the creek it was meant to protect. When fish carcasses turned up downstream, Teck was ordered to pay $1.4 million in fines.

Despite pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into water treatment efforts, the problem continues to dog the mining company. In March, Teck agreed to purchase a new drinking water well for Sparwood when selenium concentrations in one of its three existing wells started to exceed provincial guidelines. That’s after the town had taken to installing cameras around a nearby mine after residents complained about coal dust clouds repeatedly settling over the area.

The grizzly bear population also declined by 40 per cent over an eight-year stretch in the Elk Valley, which researchers suggest is in part due to increased human-wildlife interaction around the mining towns. Given the Elk Valley and Livingstone Range are two sides of the same continental divide, scientists say there’s a good reason to expect similar environmental issues in southwestern Alberta if coal mining is permitted at a similar scale.

And the concerns extend beyond southern Alberta. Coal leases stretch hundreds of kilometres to the north in Alberta’s Rockies and Foothills, cutting through grizzly and elk ranges. The headwaters of the North and South Saskatchewan rivers, which provide water for much of the Prairies, pass through land claimed by coal companies.

“Any project, no matter what, comes with some degree of risk,” says Petr Komers, a Calgary-based environmental consultant. “So if you create a mine in the headwaters of what people drink in Edmonton, there is some amount of risk — it’s not zero — that something will occur.”

And things have occurred. Things like the Obed Mountain mine spill.

On Oct. 31, 2013, an earth berm at the open-pit coal mine near Hinton failed and an estimated 670 million litres of slurry from a tailings pond was released. It poured into two nearby creeks, then the Athabasca River, carrying high levels of mercury, lead and cancer-linked hydrocarbons along with it. The plume of contaminants was tracked for weeks as it travelled more than 1,000 kilometres, eventually reaching Lake Athabasca. Years later, scientists were still trying to determine the full extent of the environmental damage. The company pleaded guilty to several federal and provincial charges and was ordered to pay $4.5 million in fines.

Back in Crowsnest Pass, the proposed coal projects have also raised alarm among the local tourism industry, which has experienced its own resurgence since the 1980s.

Shane Olson, owner of a local fly fishing shop, sees his own work as diametrically opposed to mining. The two cannot successfully coexist, he said in a letter to the joint provincial-federal panel overseeing the Grassy Mountain project.

“There are a small but passionate, persistent, and ever growing group of Albertans that make a living off the land without having to dig up, cut down or otherwise compromise our natural beauty,” he wrote.

“If I don’t have clean water I don’t have fish for clients. If I don’t have fish for clients I don’t have a job.”

And it’s not just people making their living in nature who are worried.

Parks and recreation

In the wake of the coal policy being rescinded, environmental groups and outdoor recreationalists began inspecting other recent policy decisions under a new light.

In particular, there’s renewed skepticism about the government’s plan to remove 164 sites from the provincial parks system. When you plot those sites on a map, about a third of them lie in swaths of land previously protected by the coal policy.

If you look even closer, some are directly in the path of a proposed coal project.

Atrum Coal has the rights to a nearly contiguous 40-kilometre stretch of leases in the Livingstone Range. Those leases completely encircle two provincial recreation areas set to be removed from the parks system — the Oldman River North and Racehorse Creek sites — and encroach within 100 metres of a third: Honeymoon Creek.

It’s unclear whether there’s a direct connection between the coal policy being rescinded and the parks being delisted, but critics note both policy changes came out of the blue for most Albertans, who were caught unaware either was even being contemplated.

When it announced the coal policy rescission in May, the government said it would leave it up to the Alberta Energy Regulator to approve new coal projects on a case-by-case basis. Then in June, the government introduced new legislation that would allow the provincial cabinet to impose deadlines on the AER, with the goal of speeding up decisions. This comes on the heels of major budget cuts to the regulator, which has been forced to lay off hundreds hundreds of employees as a result.

Katie Morrison, with the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Association, worries about the cumulative effects of asking the regulator to take on more responsibility with fewer resources and tighter timelines.

“It’s all very concerning and, I think, all adding up to a bigger, more concerning picture of how this government views the environment and public land management,” she says.

Since the coal policy was rescinded, the AER has received new applications for coal exploration programs and exploratory drilling permits, some seeking to drill as deep as 400 metres, on dozens of sections of former Category 2 lands just north of Crowsnest Pass.

The nearby Piikani First Nation has officially supported the Grassy Mountain project, but other Indigenous groups have expressed concern about the lack of consultation before the coal policy was rescinded.

"We have treaties in Alberta,” says Marlene Poitras, the Alberta regional chief of the Assembly of First Nations.

“We have Treaty Six, Seven and Eight — that's the whole province. And governments have a duty to consult with First Nations and, in this case, it wasn't carried out adequately."

The approach to killing the coal policy stands in contrast to how it was created. After announcing its plan in the March 1976 throne speech, Lougheed’s government spent months consulting with industry, considering alternatives and crafting the details, before the policy was finally adopted in July.

Prior to even announcing the plan, the provincial government had commissioned a study about how new mines might affect tourism in southwestern Alberta. Thousands of people fishing along the banks of the Livingstone and Oldman rivers were interviewed, and the report concluded there was an “overwhelming opposition to coal mining” among these recreationalists.

In this 1977 interview, Alberta premier Peter Lougheed defends his Coal Development Policy from critics who accused his government of suppressing the coal industry.

A year after the coal policy was introduced, Lougheed defended it from critics, some of whom even accused the Alberta government of deliberately suppressing coal production in order to boost demand for oil. Lougheed rejected that assertion and said the issue, for him, was that "coal has much more serious environmental problems" than oil, particularly when it comes to scarring the landscapes Albertans hold dear.

"Most of it's located in some of the most beautiful parts of our province and would affect, for example, our potential for recreation and tourism," Lougheed told CBC News in September 1977.

Around this same time, 600 kilometres to the north, the pros and cons of having a coal mine in your backyard were playing out in a different way.

III.

Boom town goes bust

Grande Cache was one of the later entries in the long list of company towns that sprang up near coal mines in 20th-century Alberta.

Construction of the town started in earnest in 1969, in order to house workers with the McIntyre Porcupine mine, which dug up steel-making coal. The sudden appearance of a vibrant community in a remote area north of Jasper National Park caught the attention of the New York Times.

“The town of Grande Cache, financed mostly by McIntyre and the Alberta Government, did not exist two years ago,” reads an article from 1971 under the headline “Boom Town Is Built on Coal.”

The Times correspondent marvelled at the three-storey apartment blocks, 364-seat beer hall and “N.H.L.‐sized hockey rink” in the town of 2,500 people. A manager with McIntyre’s coal division told the reporter the population of Grande Cache could triple within four years, “depending on new contracts” the mine was hoping to sign with international steelmakers.

But that prediction never came to pass. Sky-high coal prices came back to Earth the following year, and the mine lost about $7 million in 1972. The company ended up cancelling a 15-year contract with its existing Japanese buyers in 1973, in order to negotiate a more limited agreement, and laid off 150 people — nearly half its workforce at the time.

The town suddenly found itself overbuilt and its viability was thrown into question. The province appointed the “Grande Cache Commission” to inquire into the municipality’s woeful financial situation. The commission concluded Alberta should avoid building “company towns” in the future.

The government made that formal — in the 1976 coal policy. The document says the province “recognizes the weaknesses of ‘one-company’ or even ‘one-resource’ based communities and will promote economically feasible diversification wherever possible.”

Over the next half-century, the boom-bust cycle would repeat several times in Grande Cache.

The penultimate boom came in the early 2010s. As coal prices surged again, a pair of Asian commodity-trading firms teamed up and bought Grande Cache Coal in 2012 for $1 billion, paying a 70-per-cent premium over the company’s share price at the time. Coal prices crashed almost immediately. By 2014, the new owners were riddled with debt. They gave up and sold the company — for $2.

The mine closed in 2015, throwing hundreds out of work. The spinoff effects led businesses of all kinds to close up shop overnight. Homeowners walked away from their houses. The town was in crisis, again.

From 2017: Alberta coal town struggles with mine closure

New owners took over the mine in 2018 and re-started operations amid a new rally in coal prices. This may have staved off the worst of Grande Cache’s problems, but it didn’t solve them.

In September that year, residents voted to dissolve the town and have it absorbed into the surrounding Municipal District of Greenview, which had already been supporting the town’s operating budget to the tune of millions of dollars per year. In total, 1,065 people cast ballots in favour of dissolution versus 32 against. There was little room to argue with the 97-per-cent mandate.

Duane Didow now represents Grande Cache as a councillor for the M.D. of Greenview. While the re-opening of the mine brought jobs back to the community, he believes a long-term solution is needed, and thinks increased tourism will help.

“Be it maybe a ski hill or increasing what we have — the whitewater rafting, golfing, the recreation opportunities on trails here are endless … that’s kind of where I think we can go,” he told CBC News in December.

Since then, coal prices have plunged again, in the wake of reduced demand related to COVID-19. In May, the mine’s current owners announced plans to suspend operations due to the pandemic.

The reason for this particular market crash may be novel, but it’s just the latest cycle in a long series of booms and busts.

Fickle markets and the future

To understand the markets for coal, you have to separate the two types: the lower-quality thermal coal (used to produce electricity) and the higher-quality metallurgical coal (used to make steel.)

In most developed countries, the thermal coal market is “in a very sharp, structural decline,” says Taylor Kuykendall, a senior mining and energy reporter with S&P Global Market Intelligence. Like Alberta, many places are moving away from coal-fired power plants.

“Metallurgical coal is quite a different story,” Kuykendall says.

“Steel demand — and thus metallurgical coal demand — is a completely different beast.”

Whenever large countries are building modern economies or embarking on a stimulus-spending infrastructure spree, they need lots of steel, and the price for metallurgical coal swings up. When the building stops, the price drops.

Some price swings are also supply related. Australia is the largest coal exporter in the world and Kuykendall says the weather in Australia, especially during hurricane season, is “one of the major things that affects the metallurgical coal market.”

Mining projects are meant to operate for decades but, as Grande Cache knows, continued operation requires prices to stay high enough to turn a profit. Companies will produce coal at a loss for a short while, Kuykendall says, because it costs more to shut down and restart an operation. But eventually, they will cut their losses, along with the mining jobs.

“That’s something that’s really difficult to plan an economy around,” he says.

Short-term fluctuations aside, there may be longer-term clouds brewing on the horizon for metallurgical coal. Earlier this year, a pilot project in Sweden was successful in producing commercial-grade steel using hydrogen as a fuel source. It marked the first such use of hydrogen with existing steel-production equipment.

The technology is very new and far from being disruptive on a wide scale. But Blake Shaffer, an economist with the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, says it’s not out of the realm of possibility that hydrogen could alter the metallurgical coal market within a decade or two.

Prices for hydrogen are generally coming down, he notes, while prices on carbon emissions are generally increasing. And creating steel from coal is a major source of greenhouse gas.

Shaffer says steelmaking has traditionally been seen as a “hard to decarbonize sector” because demand for steel is not going away and coal is essential to the tried-and-true method of making it. But if reasonably priced hydrogen, produced with low or zero emissions, could be used instead, it could lead to a tipping point that spells the end for many coal mines.

So, if Alberta allows new coal projects in the Rockies, he wonders how long those future mines will be able to operate at a profit.

“Sure, that might be the case for the next 10 years, but what do the next 20 give us? Right around the time when we’re going to be facing liabilities from open-pit metallurgical coal mines — cleaning up the tailings and surface disturbance — are we going to be facing a world where we are no longer predominantly making steel from metallurgical coal?” Shaffer says.

“I’m worried there isn’t a long-term future, if this hydrogen steel production really does take off.”

The balance

Drive east from Crowsnest Pass and the grey peaks fall away. You soon find yourself in the rolling green ridgelines near Pincher Creek.

The wind howls through this area, often gusting over 100 km/h. And Alberta is capitalizing on that potential. Hundreds of turbines now stand like sentinels along the rolling hills, creating electricity for the grid and high-paying jobs for the people who maintain them.

“They’re out there working every day,” says Pincher Creek Mayor Don Anderberg.

The industry has been such a boon to Pincher Creek, it has adopted a turbine as part of its official logo.

Fifteen years ago, Anderberg says the town had one of the oldest median ages in Alberta. Today, it’s among the youngest. But at about 3,700 people, the community hasn’t gotten any bigger. He hopes the Grassy Mountain project in the Crowsnest Pass will be approved and, through a bit of commuting, push the town over that hump.

“Having even 200 or 300 more people here would make things way more solid in Pincher Creek,” Anderberg says.

He sees a certain harmony in the idea of metallurgical coal and wind power working side by side in southwestern Alberta. All those wind turbines, he notes, are mostly made from steel. And he believes mining companies will be “good corporate citizens” that can co-exist with the diverse mix of existing land users here.

“They’re willing to put their signature on a piece of paper, saying we’ll do it, so from that point of view, I really don’t have that much concern,” he says.

“And from an economic point of view, for down here, it’s huge.”

On the neighbouring Piikani Nation, Chief Stanley Grier has expressed similar anticipation for the return of coal to southwestern Alberta and what it would mean for his community.

In his letter of support for the Grassy Mountain project, he says “it is our hope” that the mine “will reduce the unemployment rate, put our highly skilled members to work, increase the quality of life on reserve and create a brighter future for generations to come.”

This optimism is not universal. As we’ve seen, there is also worry, even fear, about damage to a delicate environmental balance that could last for generations.

Van Tighem, with the Livingstone Landowners Group, worries Albertans are grasping for something — anything — that might deliver a quick shot of adrenaline to the economy, regardless of the consequences.

"It just seems like there's this mood of desperation out there,” he says. “And I don't think it's in keeping with how Albertans think.”

Laurie Adkin, a political scientist at the University of Alberta and author of First World Petro-Politics: The Political Ecology and Governance of Alberta, says coal’s promise of an economic boost can be appealing, but the benefits should be weighed against the risks — and the alternatives.

"This is not our only alternative for creating jobs and government revenue,” she says. “It's a choice. It's a political choice to do this, and it's one that privileges the fossil fuel industry, yet again."

That privilege could soon alter Alberta’s defining landscapes well beyond Crowsnest Pass.

Those lands include territory in Bighorn Country that Alberta's previous government had proposed turning into a new provincial park, less than two years ago. And, unlike southern Alberta, there are no regional land-use plans in place there.

Open-pit mining could bring new jobs and new hope to places that have long struggled, along with new investment to a province that is accustomed to financial feast and famine but has been feeling hunger pangs for a long time now. It would also mean blasting apart landscapes so that the most valuable parts of pulverized mountains can be shipped to far-away places, while hoping the toxic parts don’t make their way into the waterways here at home.

Albertans now face a decision about what they want to do with the land, their land, at a time when tectonic global changes are forcing a reckoning on this small corner of the world.

The government is desperately searching for a way to bring back the wealth. As part of that search, it has rapidly enacted wide-reaching changes, with little forewarning or conversation. These changes affect not just Lougheed’s coal policy but a host of other laws surrounding how we protect the land, exploit the land and honour the land.

The balance is shifting, quickly.