July 29, 2020

A young man clutching two hiking poles approaches a group of strangers in Bannerman Park in St. John's.

He walks unevenly. When he says hello, his words slur. Some people look away. Others stiffen. Is he here to ask for money? Has he had too much to drink?

Some people welcome the man and listen. Others brush him away with strained politeness, even outright anger.

But he persists. Even if you don’t want to hear his story, he thinks you should anyway; for Brandon Chase, it's the difference between survival and death.

On the evening of June 27, 2015, Brandon Chase — then barely out of his teens and figuring out what to do with his life — was leaving a bachelor party in Cochrane, Alta., a small bedroom community just west of Calgary. Before he left, his mother, Pamela Davis — trying to keep an eye on her son from the family home in Bay Roberts — checked the sweltering weather out west, and sent Chase a text imploring him to drink lots of water.

At 6:30 p.m., Chase and an acquaintance climbed into a white Nissan Sentra, with Chase on the passenger side. The pair merged onto Highway 1A to Calgary, but heavy Saturday night traffic blocked both lanes. According to an RCMP report, the driver made a sudden and illegal U-turn into the westbound lane, exposing the Sentra’s passenger side to oncoming traffic.

Nobody knew he'd been drinking.

A woman driving an SUV, oblivious to the incoming obstacle, couldn’t stop in time. The vehicles collided, with the Sentra taking the brunt of the impact. Chase’s door crumpled inward, crushing him.

The Sentra spun into a grassy shoulder of the highway. First responders cut off the passenger door in order to extract Chase; an air ambulance lifted him to a nearby hospital. Medics lost his pulse on the way.

Davis, meanwhile, had started her summer holidays and had just settled down for a late dinner. Before she could finish, her stepson called; she let it ring.

Her phone immediately buzzed again. Then her daughter called through Facetime. Then she noticed an onslaught of emails and text messages, one after another.

At 8 a.m. the next day, Davis found herself on a plane to Calgary. “It was the longest flight of my life,” she recalls.

Weeks after the accident, Chase lay unconscious in a hospital bed. Davis had plastered the room with family photos on the advice of a friend, hoping it would help hospital staff remember the person cocooned in a mess of tubes and wires had a life before his coma: a passion for rugby, basketball and martial arts, a formidable memory for sports statistics and a seething disdain for the Edmonton Oilers. He’d been in Alberta “to do some exploring,” Davis says. “He was trying to find himself. He worked lots of different jobs.… He wanted to train in different dojos, and find something in that field.”

Chase’s doctor had already warned Davis about her son’s prognosis. The collision had lacerated his liver and spleen, shattered his pelvis and dislocated his skull from his neck: technically, he’d been decapitated.

“Most people do not survive that,” Davis says. “Seventy per cent of people die on the scene. We learned, later, that 15 per cent die in emergency or in the ICU. Of the 15 per cent who survive, most are not rehabable.”

As the weeks passed, it wasn’t clear to anyone whether Chase would ever regain full consciousness. The family sometimes played basketball in the court outside, hoping the sounds would stir something in his memory and rouse him. His mother often placed his hands on the ball.

The summer drew to a close without any change in his condition. His medical team, losing hope that Chase would develop the capacity to enter rehab, began preparing to move him to long-term care. “Then,” Davis says, “he started to show signs he was awake.”

One morning, Chase opened his eyes for the first time, staring vacantly out at the world, his eyes not tracking movement. Davis, spending long days by his side, started leaving the TV remote in his hand. Chase would flick through the soap operas and talk shows. “We thought it was just an involuntary thing, but then he would stop on the rugby channel,” she says. “It was purposeful.”

About two months after the collision, Davis brought the family dog, Zoe, for a visit, hoping the familiar animal would stimulate Chase's senses. She lay on the bed, licking his face. Chase brightened, and he stroked her head. The medical team stared in disbelief. “My first reaction was, 'Oh God, he’s in there,'” Davis says. “'He’s in there.'”

The family documented Chase’s firsts: his first time being lifted upright, the first time he moved his right hand. His first steps were momentous: his mother filmed Chase, flanked by three therapists and gripping a walker, slowly shuffling across a hospital room. “He had to learn to walk, how to talk, how to toilet himself. Everything,” Davis says. “He had to learn all the basics. It was just like having a newborn.”

It wasn’t just broken bones and organs that reset Chase’s life. The force of impact had caused multiple hemorrhages in his skull and severed axons knitting together parts of his brain. Today, he’s considered cognitively impaired, plagued by memory problems and behavioural changes. A legal report has deemed him permanently unable to work.

Despite his injuries, Chase retained a limitless sense of humour. He swims and still trains, albeit carefully, in jiu-jitsu.

“It was hard work,” Davis says, describing long months of intensive rehab. In the end, he moved out of the hospital to a supportive living facility. His brain will never fully repair itself, but unlike the vast majority of crash victims with his injuries, he’s able to lead a full life.

Pride creeps into his mother’s voice when she talks about it. “Brandon defied medical science by his remarkable recovery.”

The driver of the Sentra was eventually charged with impaired and dangerous driving. He pleaded guilty, but was spared a harsh prison sentence; the judge deemed his disability too severe for long-term jail time. Instead, he’d spend every weekend for nearly a year behind bars. A Calgary Sun reporter described a furious outburst from Chase, also in the courtroom, minutes after the judge’s decision: “You almost killed me, f— you!”

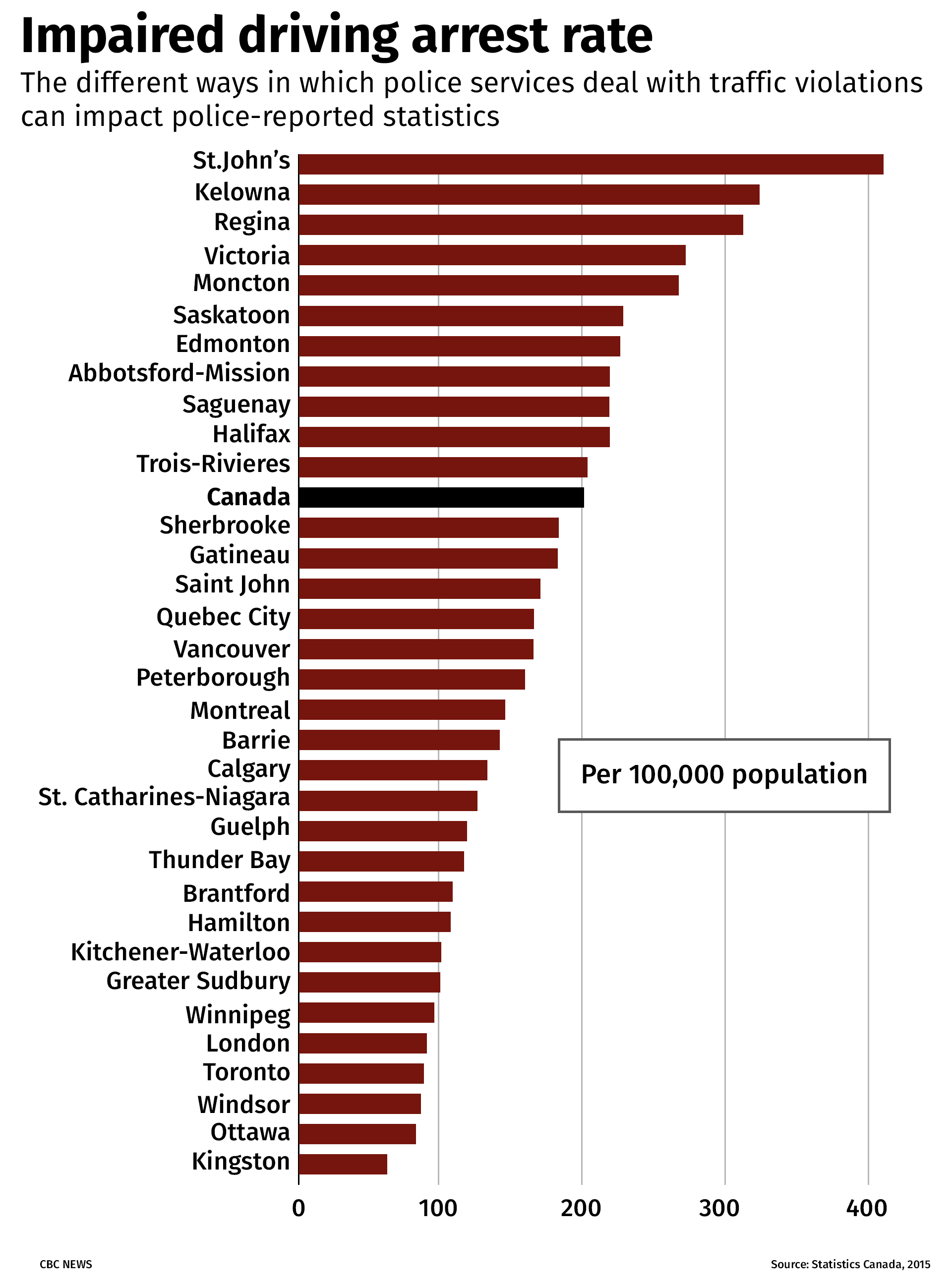

In 2015, Chase was one of 596 people injured in an impaired driving collision countrywide, according to Statistics Canada. 122 died. Despite maiming and killing the equivalent of a small town, impaired driving appears to have decreased in recent years. Arrests have plummeted across Canada since the 1980s, according to a Statistics Canada report.

Yet St. John’s still holds claim to its first-place spot among municipalities, making it a fitting backdrop for Chase to carry out his newfound passion. On hot summer days like this one, Davis drives Chase around the city. They often end up at Bannerman Park, a popular spot for lounging 20-somethings. Davis watches from the shade as Chase sets out on his mission: to introduce himself to everybody there.

Five years after his accident, Chase walks steadily, albeit with a mechanical gait, helped along by hiking poles. His facial muscles don’t work the way they used to, so he speaks slowly in an effort not to slur his words.

A traumatic brain injury often presents a host of challenges for the survivor. In Chase’s case, it’s made him socially fearless, his mother explains. “He has a lot of disinhibitions,” Davis says. “I struggled with it for a long time.”

In the early days, at a caregiver support group, Davis first encountered the concept of ambiguous loss — grief for the loved one before their accident or illness.

“At some point you just have to accept your new normal,” she said. “And what we have — you know, we have Brandon alive and well, out there doing his thing. Some people might feel offended by it, or feel very uncomfortable with that. But at the end of the day it's who he is, and I support that.”

She looks on as Chase approaches a group of people about his age, tanning on a blanket. Picnics, often accompanied by open liquor, are commonplace here. “Ma’am,” he begins, “do you want to be on CBC?”

“He said, ‘Mom, I got hit by an SUV. There’s not a lot that can hurt me right now.’”

—Pamela Davis

The woman gives him a curt “no, thank you,” a hint of annoyance in her voice. Chase politely excuses himself and walks away. The next group listens to Chase rattle off a well-rehearsed script about his accident. They empathize and exchange names. After a minute, Chase moves methodically to another sunbather; she declines to hear his story, but before he leaves, Chase quickly warns her not to drink and drive. They both wish each other a nice day. A man reading in the shade pointedly dismisses him. Chase, unflustered, heads for the next person. On it goes.

Chase guesses he’s spoken to over a thousand strangers since he started advocating against impaired driving. At first, he asked Davis to spread his story for him, suggesting she join Mothers Against Drunk Driving. “Mom was like, smiling, ‘honey, why don’t you volunteer?’” he recalls. “I’m like… good point.”

So he got to work. He didn’t need an auditorium or events — just any place with a crowd. In bad weather, he’d talk to people in malls, sometimes dodging security guards. In the summer, he’d roam downtown. One park worker, according to Davis, asked him to stop approaching people, assuming Chase himself was under the influence.

“Getting his message out is important to him, and he becomes frustrated by the fact that people often reject him because of how he speaks, or how he walks, or how he behaves,” Davis says. “But it doesn't stop him.”

“I’m very fortunate,” Chase says. But life is different now, and he uses his own brain injury to show others what one reckless decision can do: a walking example. He can’t play basketball anymore. It’s hard to have a conversation, and Chase often looks to his mother for help. Before the collision, the right side of his body was stronger; now it’s weak. He recalls the first time he was able to move it after his coma: Jose Bautista had just hit a home run. “That was a great day,” he says. “A TSN turning point, as they say.”

He knows his story doesn’t reach everyone he speaks to, but Chase looks at it as practice for the day he becomes a motivational speaker — his new aspiration. “Some people are busy and whatnot. They don’t want to hear that message,” he says. “I tell people anyway, regardless of whether they want to hear it or not.”

“People are not always accepting of anything that’s out of the norm,” Davis says. She’s afraid for him, for how people treat him. “Brandon’s speech and his uneven gait often is mistaken for him being drunk or stoned.”

Chase, with boundless optimism, assuages her worries.

“Brandon has assured me that rejection’s not a problem,” Davis says. Nearby, as his mother speaks, Chase looks around the park, scouting his next audience. “He said, ‘Mom, I got hit by an SUV. There’s not a lot that can hurt me right now.’”