March 19, 2018

In a report last week, Ontario's fiscal watchdog said the province's health care spending is not keeping pace with the demands of a growing and aging population. And across the province, chronic hospital bed shortages and backlog have been deemed a “crisis” by both politicians and clinicians.

To better understand the issues facing Ontario hospitals, CBC Toronto spent an evening in Brampton Civic Hospital’s emergency department — one of the busiest in Ontario.

This is the first story in Prescription for Change, our new series on Ontario’s health care challenges.

It’s late afternoon, and several stretchers are lining the main hallway of Brampton Civic’s emergency department.

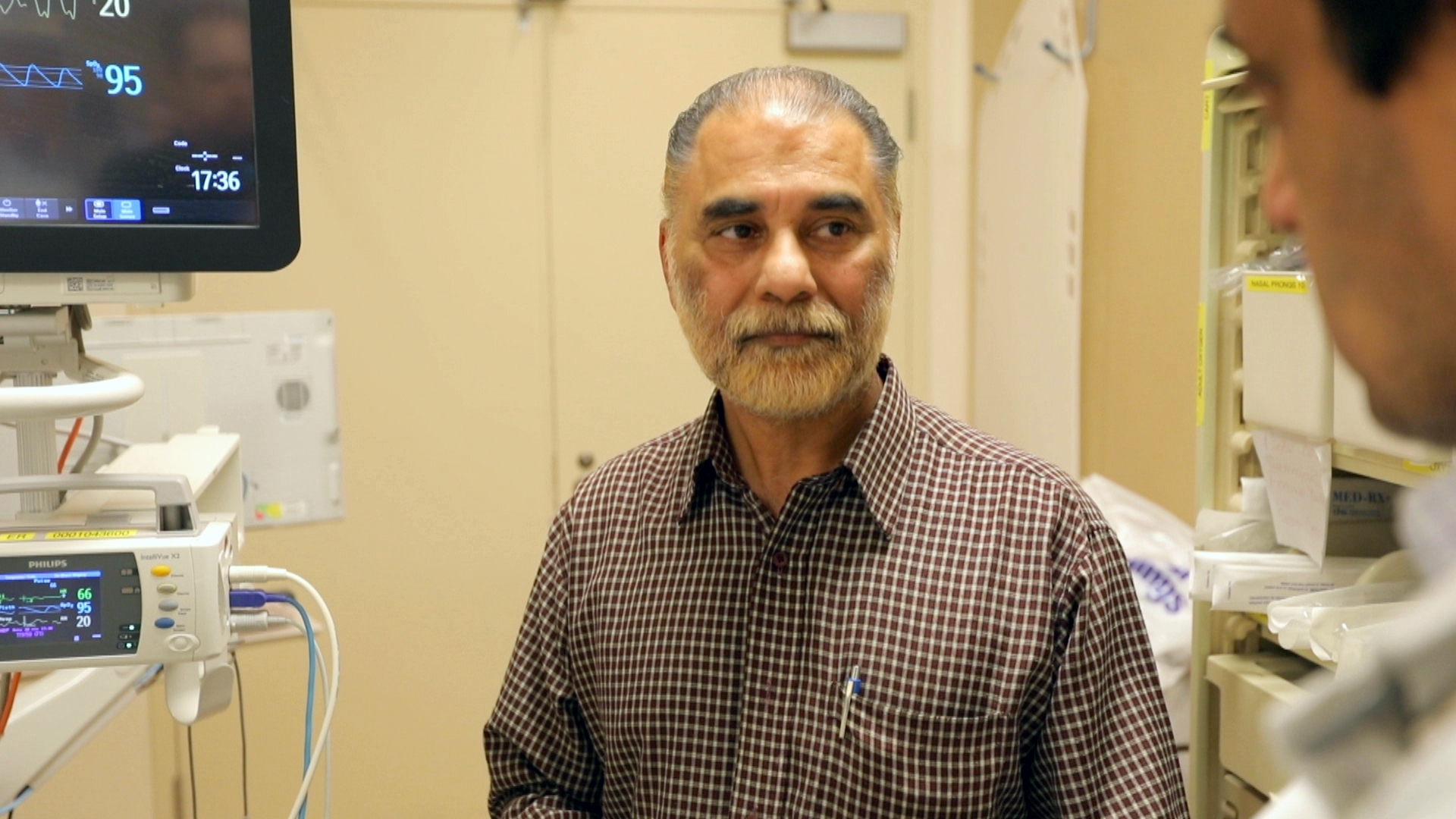

Dr. Naveed Mohammad is bracing for that number to rise.

An emergency physician for nearly three decades, Mohammad knows that even though clinicians try to see people quickly, roughly one out of every ten patients needs to be admitted to the Brampton, Ont. hospital. And they often wind up waiting in the emergency area.

Sometimes, they’re on beds in private rooms. Other times, they’re stuck on stretchers in the brightly-lit hallways, surrounded by the beeping of machines and the hectic hum of hospital staff.

As CBC Toronto reported last year, more than 4,300 patients were treated in the hospital’s hallways between the spring of 2016 and 2017, an average of roughly 12 people each day. It’s a situation known internally as “code gridlock.” And despite the province adding a nearby urgent care centre, and opening dozens of new beds since then, the bustling Brampton, Ont. facility is still struggling to provide hospital beds for a rising number of patients.

Though it was built to serve 200 patients a day, the emergency department now sees double that, says Mohammad, the executive vice-president of quality, medical affairs, and academics at the three-site William Osler Health System.

That increase stems from Brampton’s booming population growth. Census data shows the population grew more than 13 per cent between 2011 and 2016 — nearly three times the national growth rate — and its diverse communities are experiencing high rates of chronic conditions like heart disease, high blood pressure, and kidney disease.

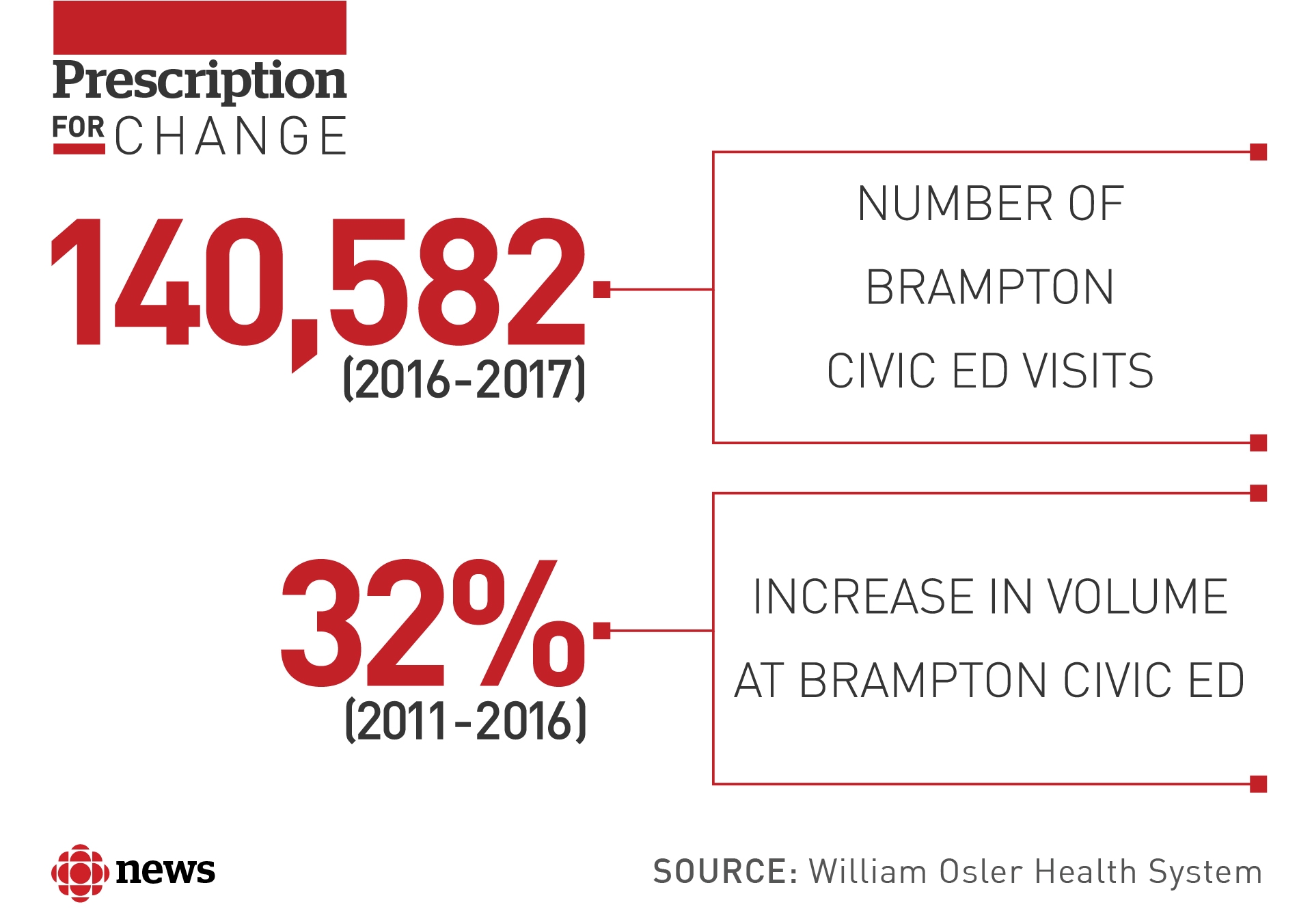

From 2016 to 2017 alone, there were more than 140,000 visits to the Brampton ED, making it the highest-volume emergency department in the province, according to data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information.

But while Brampton Civic faces unique challenges, it’s also a case study for the problems facing many hospitals across Ontario: bed shortages, jam-packed emergency rooms, and a constant backlog that’s concerning for both staff and patients.

Standing with our CBC Toronto crew in the triage area, Mohammad calls it a “frustrating” situation.

“We’re living in a first-world country that, to the outside world, has a lot of resources,” he tells us. “Yet our health care system is so challenged, and so bursting at the seams.”

Like many emergency departments, the unit at Brampton Civic feels like a maze, even with color-coded strips lining the floors. They wind through hallways, connecting the triage area and ambulance bay to other wings that focus on the broad spectrum of patient ailments, from people with minor injuries to pregnancy complications to heavily-bleeding gunshot wounds.

One door off the main hallway leads to the Ambulatory Treatment Centre, an area for patients with urgent concerns that aren’t life-threatening, like pain, fever, or shortness of breath.

Registered nurse Seema Kalotia is wearing purple scrubs and typing patient information into an electronic chart. The clock has ticked past 5:20 p.m. and the room is buzzing with activity, but Kalotia calls this a “good day.”

Some days, she says, the whole “ATC” would be full by now. On those days, staff like her need to make tough decisions, like which patient to bring in first when two critically-injured people show up at the same time. Those decisions are getting tougher as the number of patients coming in keeps ticking upwards, year by year.

“By the end of the night, we used to have like 40 patients,” explains Kalotia, who’s been a nurse here for six years. “But now, it’s like 120 you start your day with. That’s the norm.”

Across the hall, Mohammad is in the Resuscitation area, or “Resus” as staff call it. It’s a wing where staff take patients who need the most urgent care and constant monitoring — those who’ve suffered heart attacks, stab wounds, or injuries in a car accident — until they’re given a bed in the main hospital.

Since those beds upstairs are full, that wait can take hours, and when new patients arrive, often those in the private “Resus” rooms are bumped into the hallway. Now it’s nearly 6 p.m., and stretchers already encircle the main desk, creating a cacophony of beeping and humming.

In one private room, Mohammad speaks to a man in a mix of English and Punjabi. Surinder Singh Bharaj has been in the emergency room for more than 12 hours with his mother Surjit, who’s sleeping peacefully in her hospital bed. He’s worried. She’s 93, he says, and had trouble breathing overnight, which led Bharaj to call an ambulance early this morning. Mohammed informs Bharaj his mother will be heading to the coronary care unit.

“We expect her to get better, but it depends on god and the doctors,” Bharaj tells us after. “They will try their best, I know.”

Just steps away, a man waits by the main desk, near his feverish and coughing 63-year-old father on a stretcher. They’ve been in the emergency department since around 10 a.m., waiting patiently. In a room across the hall, an elderly woman lashes out at the staff from her hospital bed. “Get lost,” she cries out at the nurses.

Standing in the centre of it all at the main desk, charge nurse Robert Bouchard admits this atmosphere can be stressful for staff, who feel stretched to their limits.

“It’s emotional at times,” he says. “But you have to put that aside and try to do what’s best for the patient.”

At 6:05 p.m., a ‘code white’ alert comes over the speaker system. It’s meant to inform staff about a violent or aggressive person — possibly a patient or family member — somewhere in the hospital.

That quick signal comes as the emergency department is starting to get particularly busy, with eight patients on stretchers in the main hallway from the ambulance bay and many more in the waiting rooms of areas like the ATC.

There, Merle Francis is touching base with doctors and nurses as they manage the flow of patients in and out.

For two years, she’s been the interim manager for the emergency department, and says they’ve made drastic changes since she started, like bringing in a “flow nurse” to greet patients and let them know the next steps.

The department also worked hard to reduce patient wait times, more than doubled the number of physician shifts, and is one of only a handful of community hospitals with more than one physician working overnight.

Still, Francis says the high volume of emergency visits — which grew more than 30 per cent between 2011 and 2016 — makes preventing infections and keeping the place clean a daily challenge.

On quieter days, staff actually have time to take a breath between patients and touch-base more often with their team members. On busier days, when more than 400 patients come through emergency, everyone is “running around.”

“You can feel the pulse of the department. Everyone is just from one room to the next. There’s no time to breathe,” she says. “We’re trying to make sure patients get safe and effective care — there’s no time to stop.”

Except for us. With the clock hitting 7 p.m., our time in the ER is up.

As we walk through the main hallway one last time, we see staff lift an elderly woman from an ambulance stretcher to a hospital one, lined with blue sheets.

Paramedics burst through the ambulance bay door, bringing yet another patient into the already-crowded hallway.

And a woman sitting by a stretcher against the wall calls out to physicians as they walk past. She asks how much longer she’ll be waiting.

We’re shuffled out the door by hospital staff before we hear the answer, but it’s a safe bet — she’ll be here awhile.