December 11, 2018

Uncover: Bomb on Board is a six-part CBC podcast exploring the downing of CP Flight 21 in July 1965. Listen to all the episodes or subscribe to the podcast on iTunes or Google Play.

"In some of the areas, we had to go arm in arm through the brush because bodies were coming down. It was traumatic. Something nobody is prepared for."

Chuck Shaw-MacLaren was 37 years old when Canadian Pacific Flight 21 went down en route from Vancouver to Whitehorse. It crashed in the wilderness about 60 kilometres from 100 Mile House, B.C., where he lived and volunteered as an ambulance driver.

He was among the first on the scene, witnessing the carnage after the airliner carrying 52 passengers and crew suffered a catastrophic explosion and slammed into the forest below.

Shaw-MacLaren helped search for survivors in the thick brush of the B.C. interior, but there were none to find.

He ultimately spent three days recovering bodies scattered across several kilometres of rugged forest. Some were burned beyond recognition, others still caught in the trees that broke their fall from 15,000 feet above.

Shaw-MacLaren is sparing with the details of what he saw. He doesn’t want others burdened by the gruesome memories he’s lived with for the past 53 years.

"You have to forget it from the moment you start. That's what you're trying to do."

Even so, the 91-year-old hopes the retelling of what happened to CP 21 on July 8, 1965, will help bring to light more information about what truly happened that day.

What is known for certain is that the crash of CP 21 was a deliberate, criminal act.

"This is not an accident. This was pure murder."

"It was murder. This is not an accident. This was pure murder," Shaw-MacLaren says.

"They have explosive residue, which is pretty much a case-closed," adds Larry Vance, a 25-year veteran with the Transportation Safety Board who recently reviewed Transport Canada's original investigative notes and reports on the crash.

"This adds up pretty quick to being a criminal act, a criminal event, perpetrated by one or more people. That's the easy part," Vance says. "Now, when you get into a criminal investigation you get into the whodunit, and that is exceptionally difficult for the people who were doing that aspect of the investigation."

On July 8, 1965, Canadian Pacific Flight 21 crashed killing all 52 on board. It remains one of the largest unsolved mass murders on Canadian soil.

Within days of the crash, the RCMP determined that a bomb — likely made with dynamite or gunpowder — was detonated on the floor of the plane’s rear lavatory.

Since the bomb was placed in clear sight and no evidence of a timing device was found, the police determined it must have been detonated by one of the 52 people on board.

In a preliminary report about the nature of the bomb, explosives investigator Tom Sterling wrote: "As a matter of speculation, I suggest that either a dynamite containing potassium nitrate was used, or dynamite was used in conjunction with gunpowder. As to the quantity of high explosive used, my estimate is somewhere between about 3.5 pounds and 10 pounds of dynamite-energy equivalent."

A large team of investigators was quickly assembled, and within two weeks of the crash the RCMP had completed background checks of everyone on the plane.

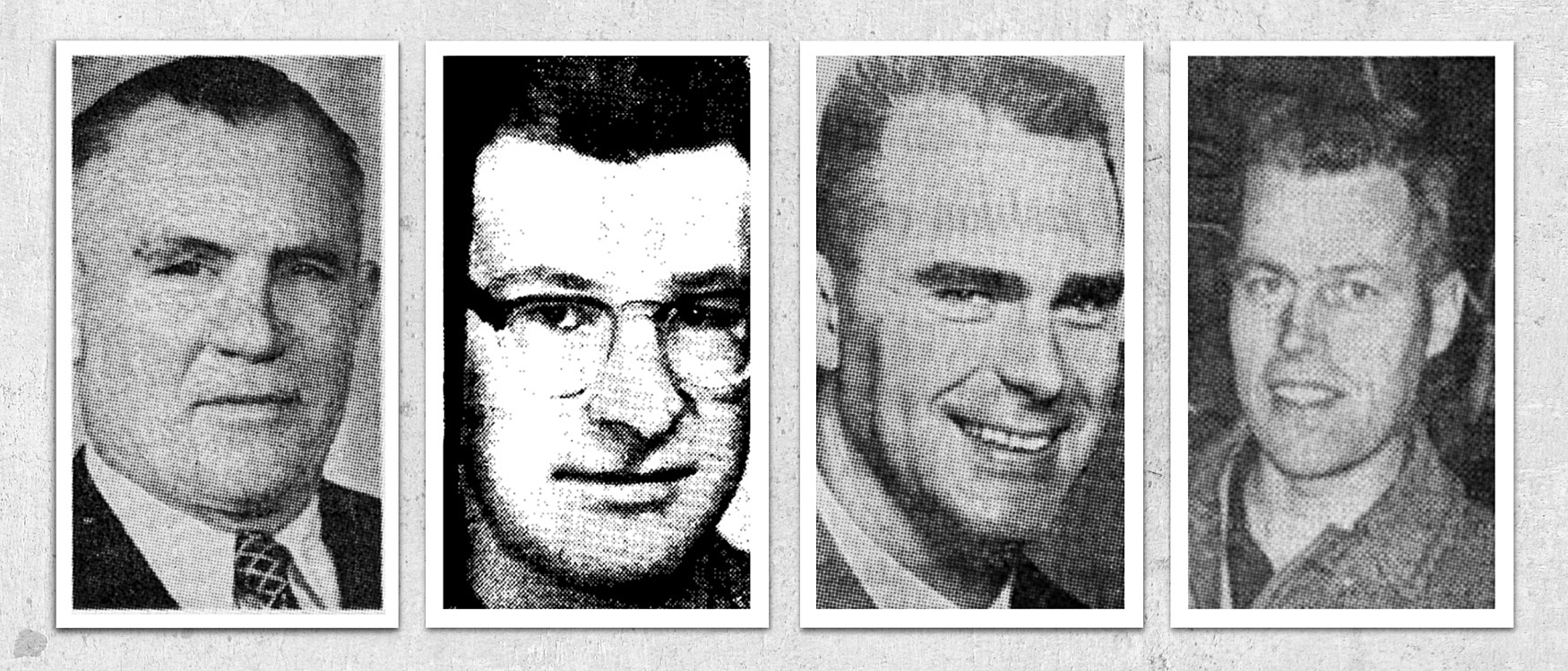

They believed the culprit was one of four men on board:

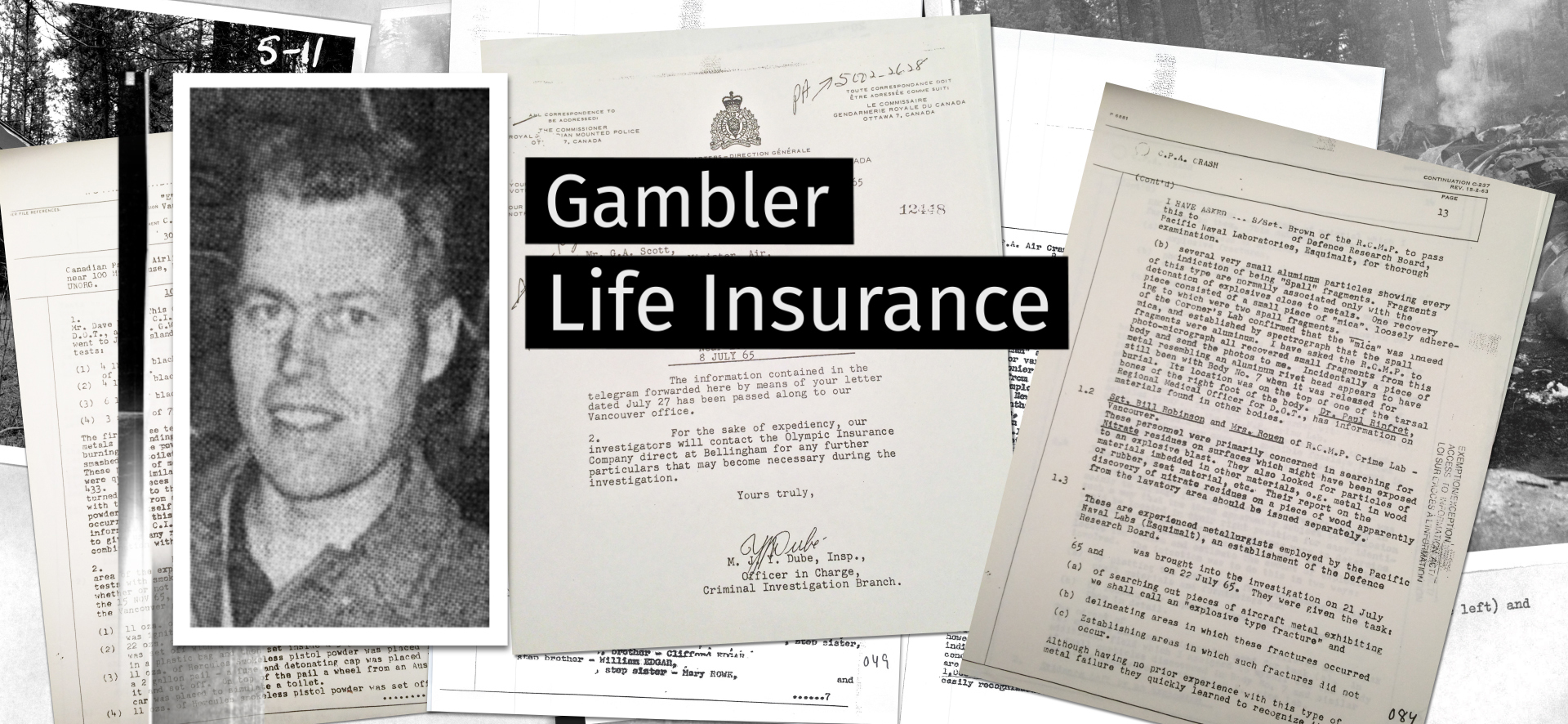

- Douglas Edgar, a gambler who purchased life insurance moments before boarding.

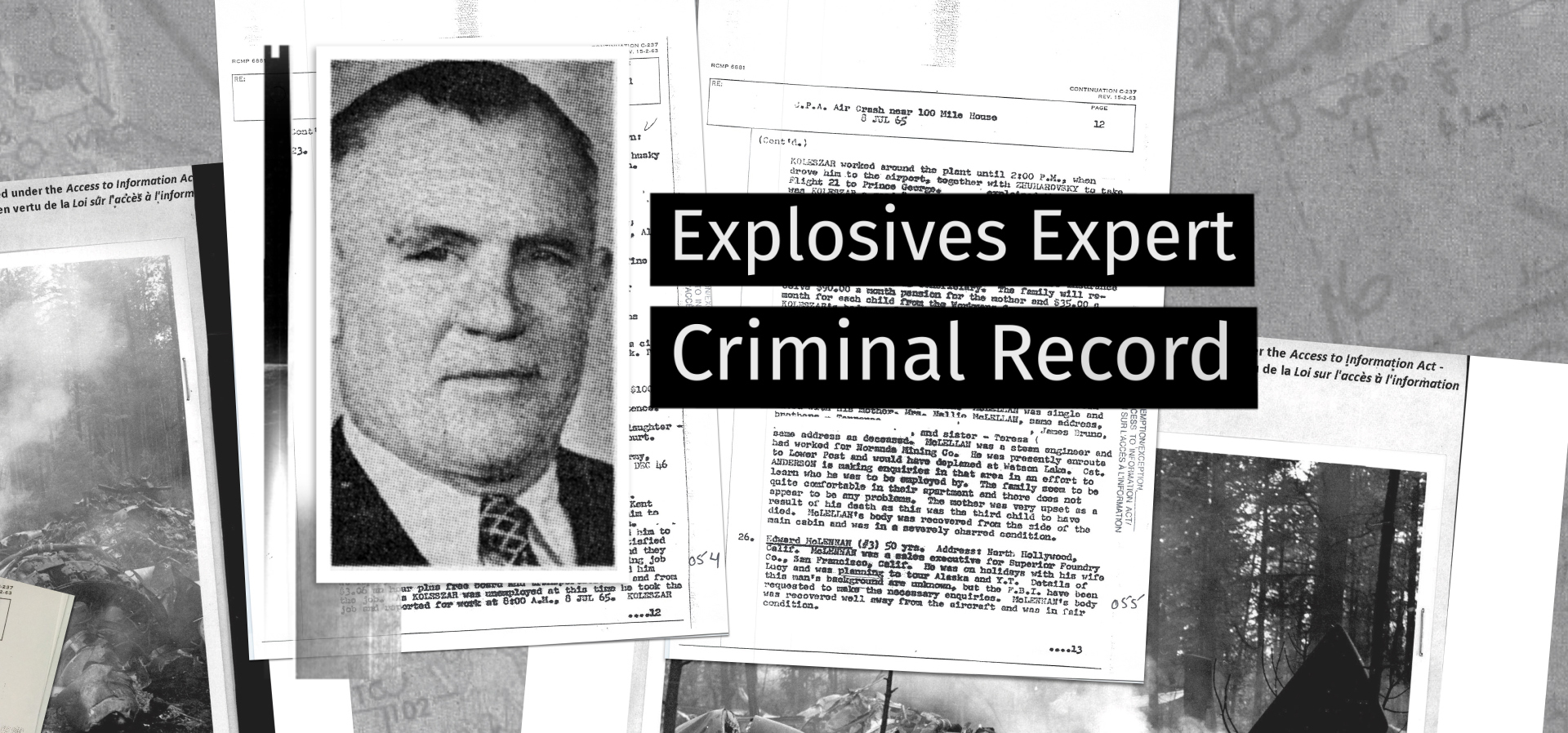

- Stefan Koleszar, a mining-explosives expert with a criminal record.

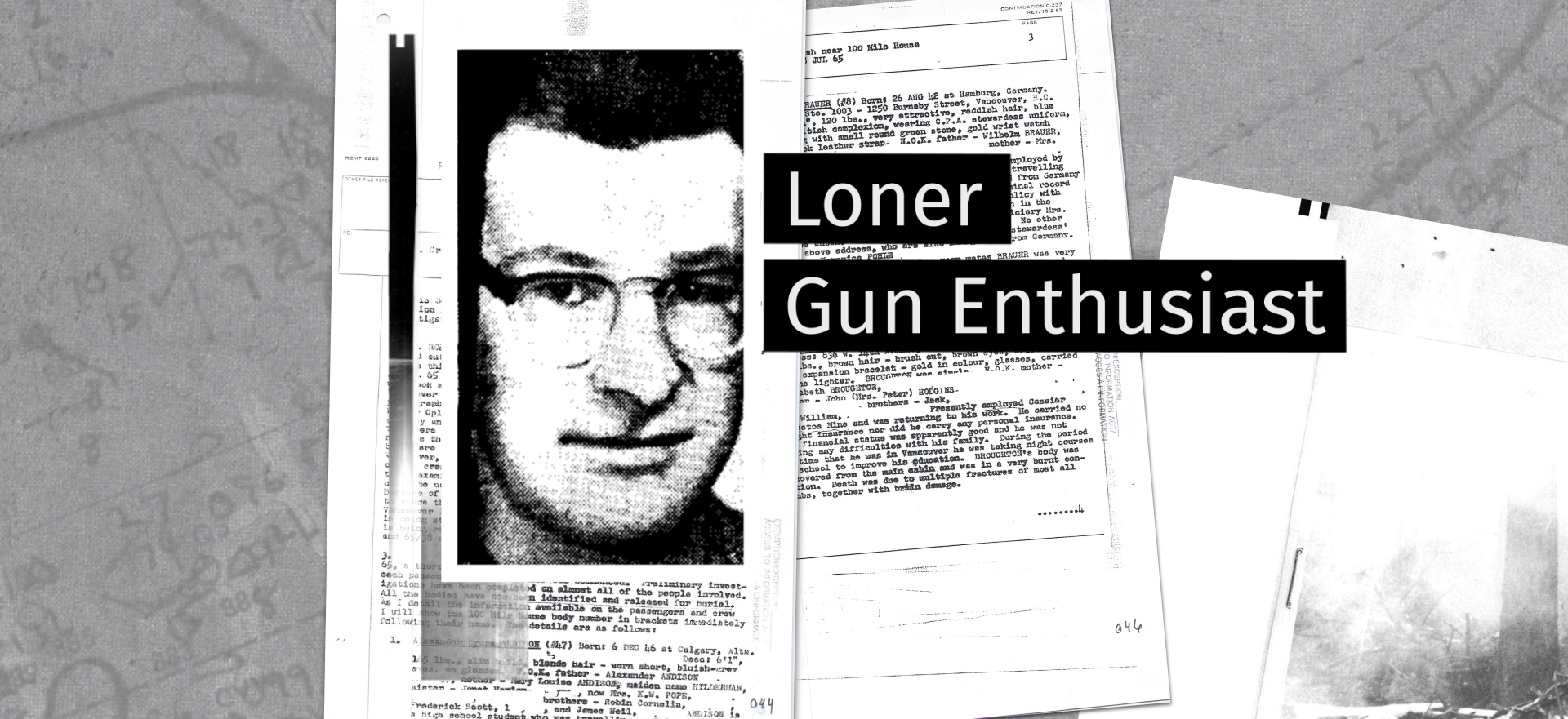

- Peter Broughton, a young man described as a loner with an interest in guns and gunpowder.

- Paul Vander Meulen, an individual who had a gun on the plane and was described by his psychiatrist as having a "deep madness toward the world."

Police conducted extensive investigations into these four men, but based on the evidence and the forensic techniques available at the time, were never able to determine who was responsible for detonating the bomb.

The case was eventually closed.

But for those who lost loved ones in the crash, there's been no closure and many questions remain.

Among the family members still looking for answers is Didi Henderson. She was five years old when her father was killed in the crash.

"This is still [one of] the biggest unsolved aviation murder crashes on the books," she says, "and not being able to know who did it means you have no place to even focus your anger."

The investigation

Five decades after the crash, CBC News has taken a fresh look at the bombing of CP Flight 21 to see if modern analysis and forensic techniques can shed new light on the case.

Over the past several months, CBC journalists interviewed dozens of individuals connected to the incident.

They also accessed thousands of pages of decades-old documentation through access-to-information requests, including the original RCMP and Transport Canada reports on the crash.

That material was then shared with a number of specialists — among them a former aviation crash investigator, explosives experts, a forensic psychologist, and a criminologist with an interest in cold cases — to determine if it was possible to get any closer to knowing which of the four suspects, if any, planted the bomb.

"This is probably one of the more remarkable cold cases in Canadian history."

"This is probably one of the more remarkable cold cases in Canadian history, in part because it is so unusual, and yet there is little to nothing that's been written on it and very few people know about it," says Mike Arntfield, a former police detective and criminologist.

He holds a PhD in Criminal Justice and now teaches at the University of Western Ontario in London. CBC hired him to help review the case.

The details of the RCMP's four main suspects, who Arntfield agrees should all be at the top of the list, are also "uncanny … it's something out of a Hitchcock film. 'Strangers on a Plane,' we could call this. Four absolute strangers, each with something to hide. Each of whom will end up being, at some point, a suspect in this case."

CBC News searched for individuals involved in the original investigation. Many of them are no longer alive, but CBC did connect with Robert Mullock, who headed the investigation for the RCMP.

Mullock did not want to speak on the record, except to say: "Yes, I did the investigation. We did a complete review, and in the end we were satisfied that the person was on the aircraft."

To better understand why certain passengers became the RCMP’s top suspects, it helps to know the two key points that formed the basis of their investigation:

- First, police believed the bomb was made up of either dynamite and/or gunpowder.

- Second, they were interested in taking a closer look at passengers who carried life insurance policies considered to be unusually large.

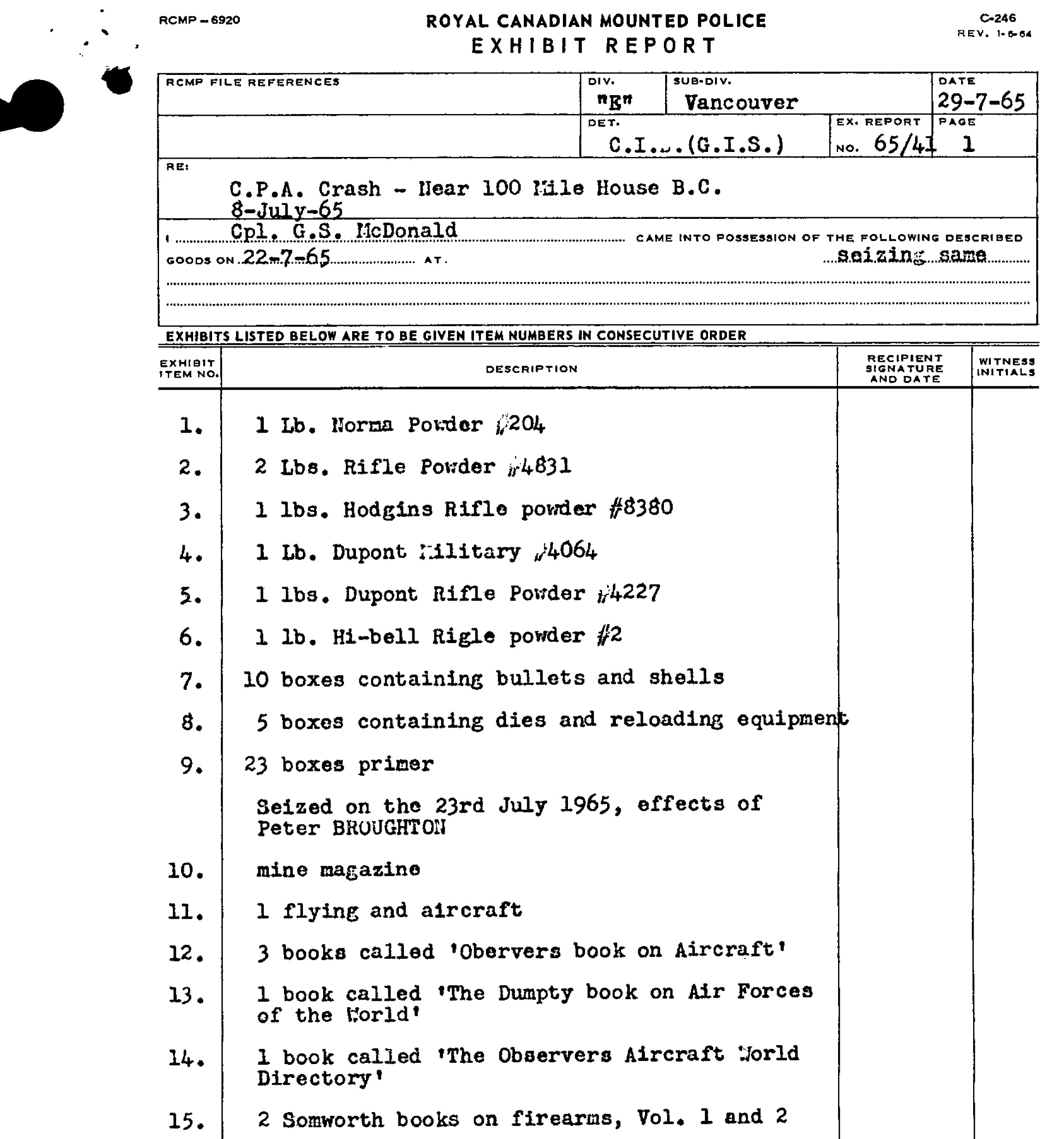

Koleszar and Broughton both had expertise with explosives or gunpowder.

And in an RCMP report dated July 22, 1965, investigators write, "None of the passengers, with the exception of Edgar and Vander Meulen, carried more insurance on themselves than would be normally expected for people in their position."

This report was followed by hundreds of pages of police notes detailing the investigation into the four suspects, including interviews with their families, friends, teachers and colleagues.

There were also deep dives into the suspects' medical records, criminal history and personal lives, and details about material confiscated from their homes.

Suspicious behaviour, links to explosives and even what books the suspects had checked out from the library were investigated and documented.

Here is what the evidence, and the analysis from the experts CBC shared it with, reveals about Douglas Edgar, Stefan Koleszar, Peter Broughton and Paul Vander Meulen. And why some of the experts believe the suspect list can now be narrowed to two names.

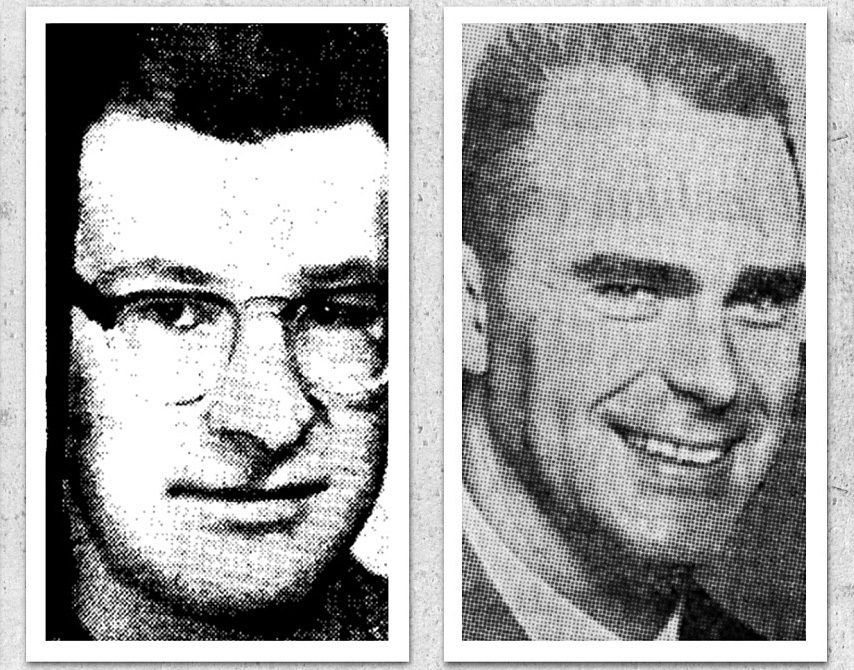

Douglas Edgar

Douglas Edgar lived in Surrey, B.C., with his wife, daughter and niece.

The 40-year-old was a tall, easygoing man who made his living working various jobs in logging and fishing, and also supported his family by gambling.

Relatives described Edgar as "a happy-go-lucky type, good to his family, who never seemed to let anything bother him."

Edgar had told his wife he was flying to Prince George on CP 21 for a job at a nearby mill.

However, when the RCMP checked into this, they were unable to find any employers who had hired him.

Edgar took "next to nothing for clothing" with him.

Further raising suspicion, police say Edgar took "next to nothing for clothing" with him on the flight.

While the RCMP found all these points noteworthy, it was the life insurance Edgar bought shortly before boarding that really drew their attention.

Events leading up to the crash of CP 21 may explain why. Between 1960 and 1965, there were three other mass-murder-suicides on planes in which financial troubles and insurance were suspected motives.

At the airport Edgar purchased four policies that would pay out $125,000 to his family in the event the plane went down, the equivalent of nearly $1 million in 2018.

While buying insurance at the airport may seem strange today, it was not uncommon in 1965. Back then, policies were available from agents and even vending machines at airports.

Lea Edgar, who now lives in California, was nine years old when her father died in the crash. In a CBC interview for this story, she says she's certain he is not the bomber and points out that there was nothing sinister about the insurance he bought the day of the flight.

"My father always had a lot of spare change in his pockets," says Lea Edgar, who was at the airport the day her father left on CP 21.

"I can even remember him giving me some of the change and putting it into the machine — not that you see newspapers anymore sold on the street, but it was like that type of coin-operated machine where you just drop the coins in. And he had me do it because a prize came out, a bundle of papers. Not particularly exciting, but it was kind of a little thing that he had us do."

Arntfield, a criminology specialist who works with modern profiling techniques, points out that the behaviour was typical of someone with Edgar's type of personality."

"This guy's a gambler, he's impulsive by nature."

"These machines and kiosks were in airports to appeal to impulse purchasing of life insurance. This guy's a gambler, he's impulsive by nature," Arntfield says.

He adds that a man like Edgar would likely have done a better job of covering his tracks if he were guilty.

"He made his living through deception, playing cards. He would have known that he would have been a primary suspect [due to the insurance purchase], and that it would have imperiled his family getting the money from the life insurance."

Arntfield also says that altruism alone, leaving money for his family, is unlikely to be a sole motivator for a such a serious crime. He feels there would need to be another motive at play.

Police considered whether Edgar’s gambling lifestyle could have been a factor, and made inquiries that turned up conflicting information.

A friend of Edgar’s told them that Edgar was a "fair gambler," who showed "little emotion whether he lost or won." The friend said he would occasionally borrow money, up to about $200, but always paid it back.

Police were also contacted by someone who claimed to know Edgar "quite well." The person, whose name is redacted in the documents CBC obtained, told them that two years prior to the flight, Edgar "had been losing money and had borrowed up to $1,000 from an unknown person." The source also indicated there may have been several others who Edgar had borrowed money from and couldn’t pay back.

Ultimately, though, the police determined that there was no evidence that Edgar was in financial trouble.

"Enquiries into Edgar’s background failed to indicate that he was being pressured for gambling debts or that he had incurred any heavy gambling losses," they wrote.

Police also looked into whether Edgar had knowledge of explosives, but found no connection.

Lea Edgar told CBC that the RCMP had done an extensive search of the family home. "They even dug up locations in the backyard, and had long metal stakes and did tests — I assume to see if there was anything buried out there. Nothing was ever found."

She also says there’s an explanation for why police couldn't confirm where her father was travelling.

"He knew so many people in the logging business, that had been his career and his history. He was probably going there [so] he could get a day job, and in the logging camps they would play cards at night. You'd make a better living at that than working with your hands."

Police say they found no indication that Edgar was suicidal and wrote that, "the only somewhat suspicious circumstances surrounding this person is the amount of life insurance taken out just prior to the flight at Vancouver International Airport."

Lea Edgar questions how rigorous the RCMP's investigation was at the crash site, and whether evidence that could have identified the bomber may have been missed.

"People who were there to try to help survivors had climbed all over and contaminated the site."

"The area had been looted. People who were there to try to help survivors had climbed all over and contaminated the site. Items were moved, changed. Who knows what else was there that was taken?"

The police did note that money was missing from at least one passenger's wallet after the crash.

Lea is angry and says the trauma her family suffered from the death of her father was compounded by him being made a suspect.

"My mother went through hell."

She says her family was also left destitute for years while her mother fought to get the insurance company payout, which they eventually did receive.

Stefan Koleszar

Another name on the RCMP’s list of top suspects is 53-year-old Stefan Koleszar.

He was described as a husky man with greying brown hair and blue eyes. A father of five, Koleszar was on his way to a new job when he boarded CP Flight 21.

Based on his reputation as an expert "powder man," a term used in the 1960s to describe someone who works with explosives, he had been hired to work on a rock-excavating job near Prince George. The company paid for Koleszar’s transportation.

Employers described Koleszar as a "hot tempered type of man," but a fair worker, a good blasting expert and "one of the most careful men they had ever employed in this line of work."

A police memo from Dec. 17, 1965, states that he could not be eliminated from the investigation, "because of his knowledge of explosives and history of violence."

Given that the RCMP's interest was primarily piqued by Koleszar’s direct connection to explosives, CBC News set out to investigate how hard it would have been to acquire the material needed to make the bomb that took down the Douglas DC-6, and what expertise its maker would have needed.

Bill Smith, who teaches blasting techniques at Sir Sandford Fleming College in Peterborough, Ont., agreed to review the RCMP's original forensics and test similar bombs.

The police were certain that a "high velocity explosive" was used to make the CP 21 bomb. Their working theory, based on evidence collected at the scene, was that it was either dynamite or gunpowder, or a combination of both.

Unlike today, Smith says these materials would have been readily available in 1965.

"As long as you were over 16, I believe you bought that right over the counter. You would go buy dynamite, blasting caps, farmers did it all the time."

At a safe testing site, Smith also demonstrated how easily a bomb with either ingredient could be rigged up and detonated manually.

Both the gunpowder- and dynamite-based bombs were simple to assemble, and both created explosions large enough to do catastrophic damage to a plane.

"It tells me that a lot of people would have had access to the materials and the means to do an explosion like that. It wouldn't have taken a lot of expertise to do what we did today on a plane," Smith says.

Which means that while Koleszar’s access to explosives and his experience working with them may have made him stand out to police, many people on the plane could have been capable of gathering the materials and know-how needed to make the bomb.

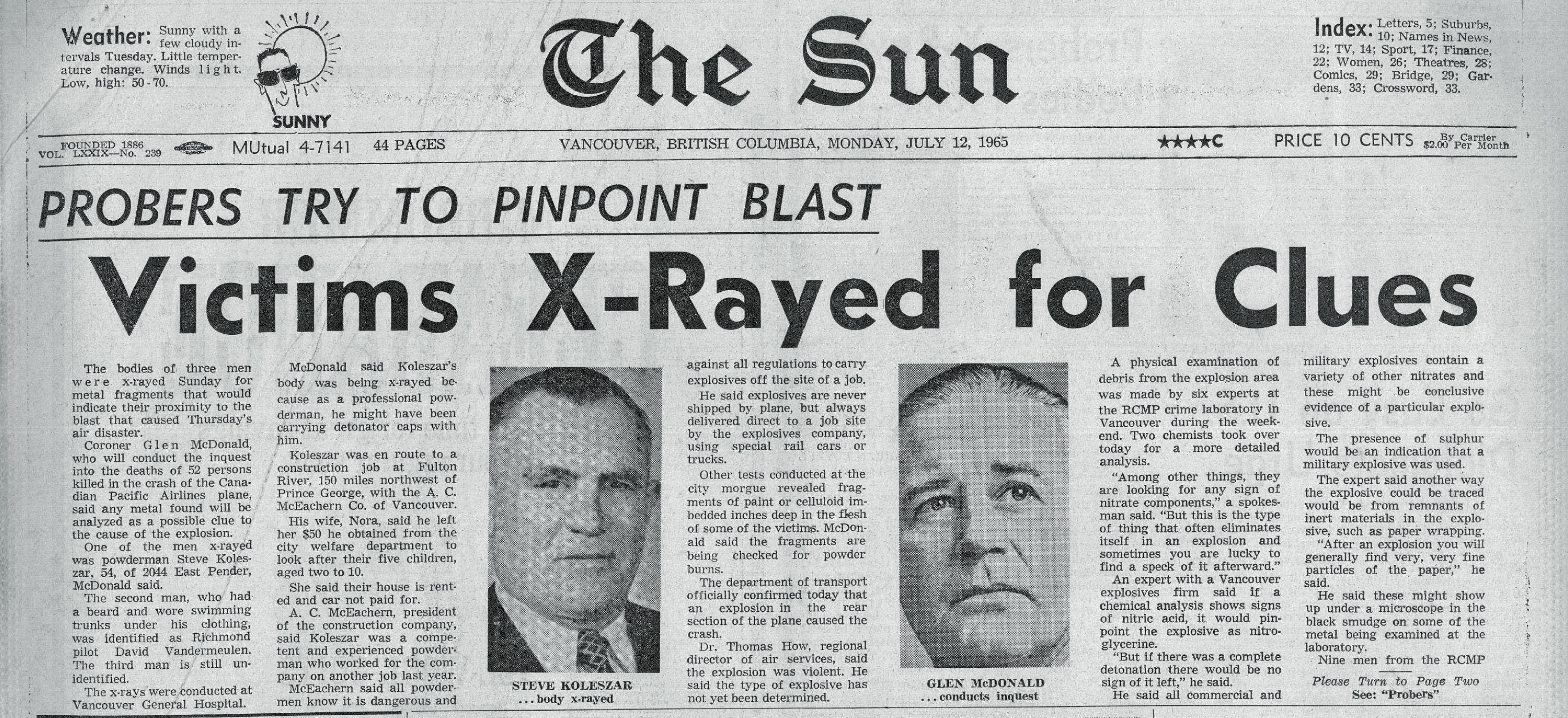

Police never did find any physical evidence linking Koleszar to the bomb. As part of their investigation, the RCMP even x-rayed his body to look for metal fragments that might indicate he was close to the blast, but found nothing.

This detail, along with several others about the case, was published in the Vancouver Sun the week following the crash. About 25 years later, Koleszar’s daughter Sandra found out her father was a suspect by reading articles like this while doing research at the Vancouver Public Library.

Sandra was six when her father died in the CP 21 crash. Her mother never shared any details about his death, but she says the loss has always deeply affected her.

"I remember when I was smaller, I would look around and wonder if my dad is alive, and looked for him in a crowd."

“Even right now, I can't believe the effect it has on me when I talk about it," Sandra says. "I remember when I was smaller, I would look around and wonder if my dad is alive, and looked for him in a crowd."

She adds that what she learned from the newspaper articles during her library research was completely unexpected.

"It was really shocking to see that, because we did not know anything about that. They said our father was a suspect, plus they wrote other things about our father that we did not know he did. They said he had a fight with somebody in 1958, he killed somebody."

Koleszar's criminal record was the second thing police noted about him as a suspect. It listed a number of charges including "carnal knowledge," assault, and murder.

The latter resulted from a fight with another man that ended when Koleszar "threw him out and down the stairs," causing him to die from a "ruptured heart." The murder charge was later downgraded to manslaughter and he was ultimately acquitted.

Koleszar was also discharged from the military for misconduct when he was in his 30s, but the reports do not specify why.

In addition to his employers, police interviewed Koleszar’s family doctor. He told them that Koleszar was generally a healthy man, although he suffered from an inferiority complex. The doctor stated that Koleszar, "was a Ukrainian and when people called him a bohunk he became very upset, and that often resulted in getting into a brawl."

The doctor also told police there were no indications Koleszar had any mental illness.

Criminologist Mike Arntfield says he doesn’t give too much weight to Koleszar’s criminal record, because "a history of hot-blooded violence" has a different psychological profile from the calculated mass-murder committed on CP 21.

Arntfield used a computer algorithm to compare the CP 21 case to other aircraft disasters, mass murders, suicide bombings and actions by suicidal individuals. There was little about Koleszar that fit the profile of a likely bomber.

Arntfield says his age is also a poor statistical match for the type of person who usually commits this type of crime.

"When we look at hundreds of other acts of mass murder since then, his age for the use of a bomber-initiated device is too far off statistically," Arntfield says.

Forensic psychologist Michael Woodworth also told CBC that research indicates the age profile of mass murderers is generally in the range of 17 to 34 years old.

Woodworth does caution that there are only a small number of cases to base these statistics on, however, and it’s an even smaller number when specifically referencing mass murder-suicides on planes.

"Especially outside of ones that are for terrorism purposes these days, the rate of them is so low."

Peter Broughton

Peter Broughton was another passenger with a strong connection to explosives.

Broughton was 29 years old and single. He had a good relationship with his family, which included two brothers and one sister.

His friends described him as intelligent, but reserved and socially isolated.

He "did not care for people who talked too much, and preferred to be by himself," his mother told police.

Broughton had been living in Vancouver and taking night courses to improve his education. Following the crash, his sister told police he had been planning his future career and was quite interested in aviation and electronics.

When he boarded CP Flight 21 he was returning to Cassiar, B.C., where he worked monitoring machinery at a mine.

When he wasn't working or studying, Broughton’s passion and hobby was guns and reloading ammunition. He owned a number of firearms and was the armorer of a gun club in Cassiar.

It was this skill with gunpowder that first caught the attention of police. Their interest deepened as the investigation unfolded.

CBC News met with Ken Leyland, whose late father Cy was the lead investigator for the Department of Transportation in 1965 and worked closely with the RCMP. Cy died 18 years ago, but before he passed he told his son that the RCMP thought Broughton was most likely the person who set off the bomb.

"I asked him point blank, I said 'do you know who did it?' And he said, 'we have a very good idea who the responsible person was,'" Ken Leyland says.

Cy told his son there was a lot of evidence pointing to Broughton, "but it's all circumstantial."

"Broughton had been in Vancouver," Ken says, "and while he was there he went to the Vancouver Public Library and checked out a book on Douglas piston-powered airliners, of which DC-6Bs were one. When the RCMP visited his mother's home, the book was still there along with a one-pound can of 60 per cent natural black gunpowder with approximately four ounces left."

CBC looked into this, and discovered that the details in the police reports did not all line up with those recounted by Cy. While the RCMP did retrieve a number of cans of gunpowder from Broughton’s home, for example, none were the black gunpowder thought to have been used in the bomb.

"Over the past six months [Broughton] had shown a considerable interest in the the construction of aircraft."

Police said there were five books on aviation, none of which were about the Douglas DC-6 specifically, although they noted that, "over the past six months [Broughton] had shown a considerable interest in the the construction of aircraft."

As for motive, according to Cy Leyland, the RCMP believed Broughton may have set off the bomb in a bid for attention.

"One of their working theories with this individual was that he felt the airplane wouldn’t be destroyed ... and he would have his 15 minutes of fame, because he was one of the passengers," Ken says his father told him.

There is nothing in the reports to indicate this is what the RCMP officially believed Broughton’s motive to be. But notoriety is a known motivator for crimes such as this, says Woodworth, the forensic psychologist.

"However, in most of these cases we have some evidence they were planning this, or they made a statement after the fact or beforehand."

When asked by police if Broughton would commit this this type of crime, a doctor at the mine where he'd been working said "no," but that "a youth such as Broughton who kept to himself and kept everything to himself would likely commit suicide in this manner to get attention."

What the doctor meant by "youth such as Broughton" is unknown, but it’s clear from the reports that the RCMP were investigating Broughton’s sexual orientation and whether it might have factored into a motive.

"We are exploring the possibility that there was a homosexual love affair," write police in reference to a relationship they suspected Broughton may have had with another man. "If this love affair had been broken off recently, it is known that homosexuals become very despondent when this occurs."

While this notion is understood as prejudice today, in 1965 homosexuality was a criminal offence.

"You have a police culture that is oriented around seeing something wrong with homosexuals," says Gary Kingsman, a professor emeritus at Laurentian university and co-author of the book The Canadian War on Queers: National Security as Sexual Regulation.

"So there’s this association on the part of the police [that] … there's something wrong with their character. Something vulnerable, something risky, something suspicious."

Later in the investigation the RCMP said they had "failed to enlarge on the suggestion that Broughton was homosexual." But they continued to write that he was the "most logical suspect."

There is one more piece of evidence that Arntfield says raises a red flag that he "cannot get over."

When the RCMP interviewed Broughton’s mother following the the crash, investigators say she told them her son had warned that "there was something dangerous in his room" two nights prior to the crash.

She later denied making this statement to police, but Arntfield believes it may be a key piece of information.

"We don't know if that was a distraction or diversion so that she didn't enter until long after the aircraft had gone down. Maybe It was a note explaining his rationale for doing this, a suicide note of some kind. Maybe it was the device. We don’t know."

Those who knew Broughton best told CBC News they are not convinced that Broughton would ever detonate a bomb and kill himself along with 51 innocent people.

"There is no way, that’s just not something he would do. I’m sure, in my heart I know he wouldn’t do that," says Broughton's sister Joan Hodgins.

"He was a happy kid. He liked to read, he liked his music, he loved hockey. He loved his nieces and nephews. And he was very good to his mom."

In an interview with police in 1965, Joan said she had helped Broughton pack his flight bag prior to leaving and saw nothing suspicious. Even today, she recalls taking him to the airport and how he was in good spirits while there, playing with his niece and nephew before boarding.

"Now you tell me if a person like that would do such a terrible thing to his family," she told CBC.

Paul Vander Meulen

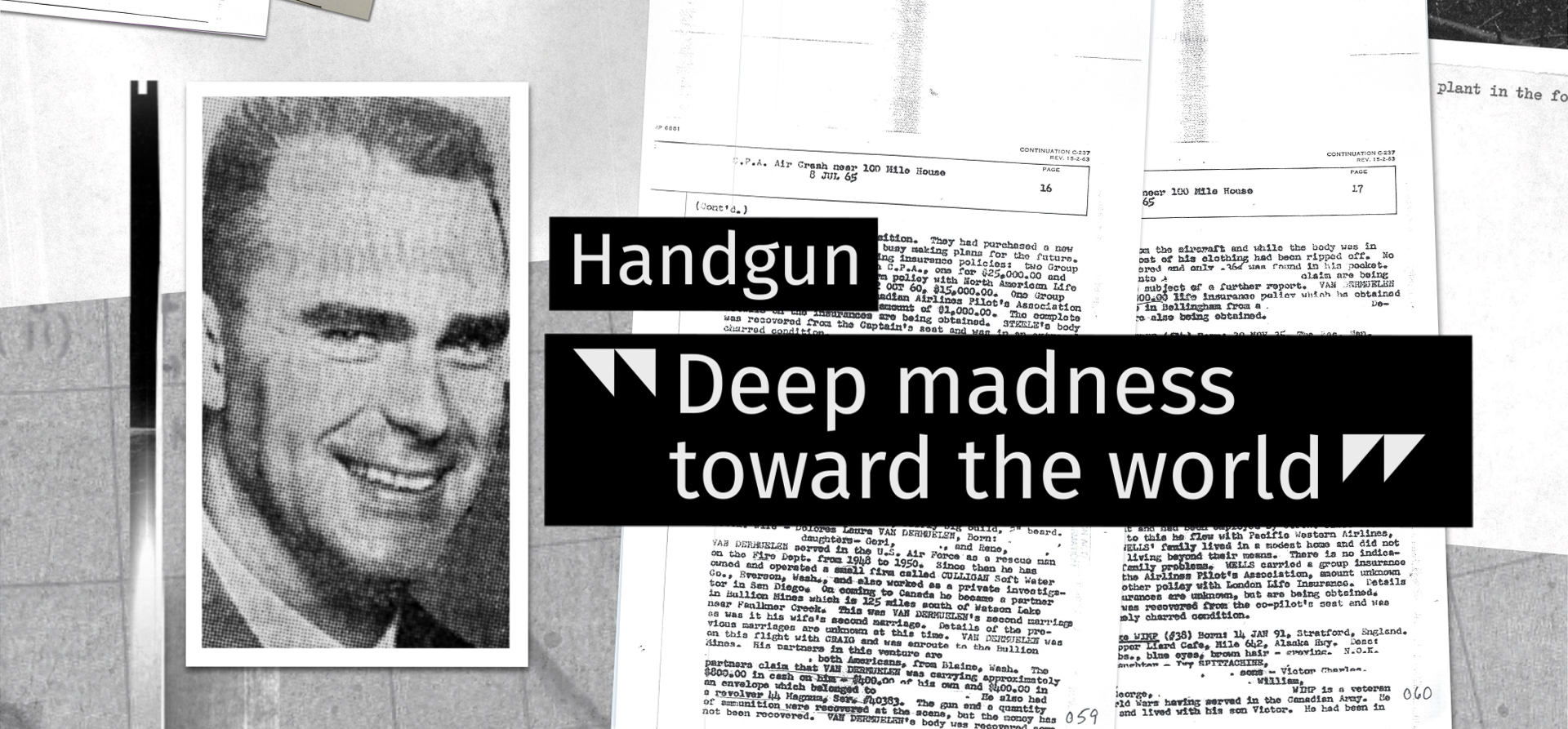

The fourth passenger topping the RCMP's list of suspects is 35-year-old Paul Vander Meulen.

He had moved from outside Bellingham, Wash., to Richmond, B.C., three weeks prior to the flight. Married to his second wife, he had two daughters from his first marriage, and two more from his second.

Vander Meulen had joined the Army Air Force out of high school and served for two years before leaving. Following that he worked at a number of jobs, including becoming a licensed private detective and running an unsuccessful water softening company.

In the months leading up to the flight he became a partner in a company called Bullion Mines, and was headed to the interior of B.C. to go prospecting.

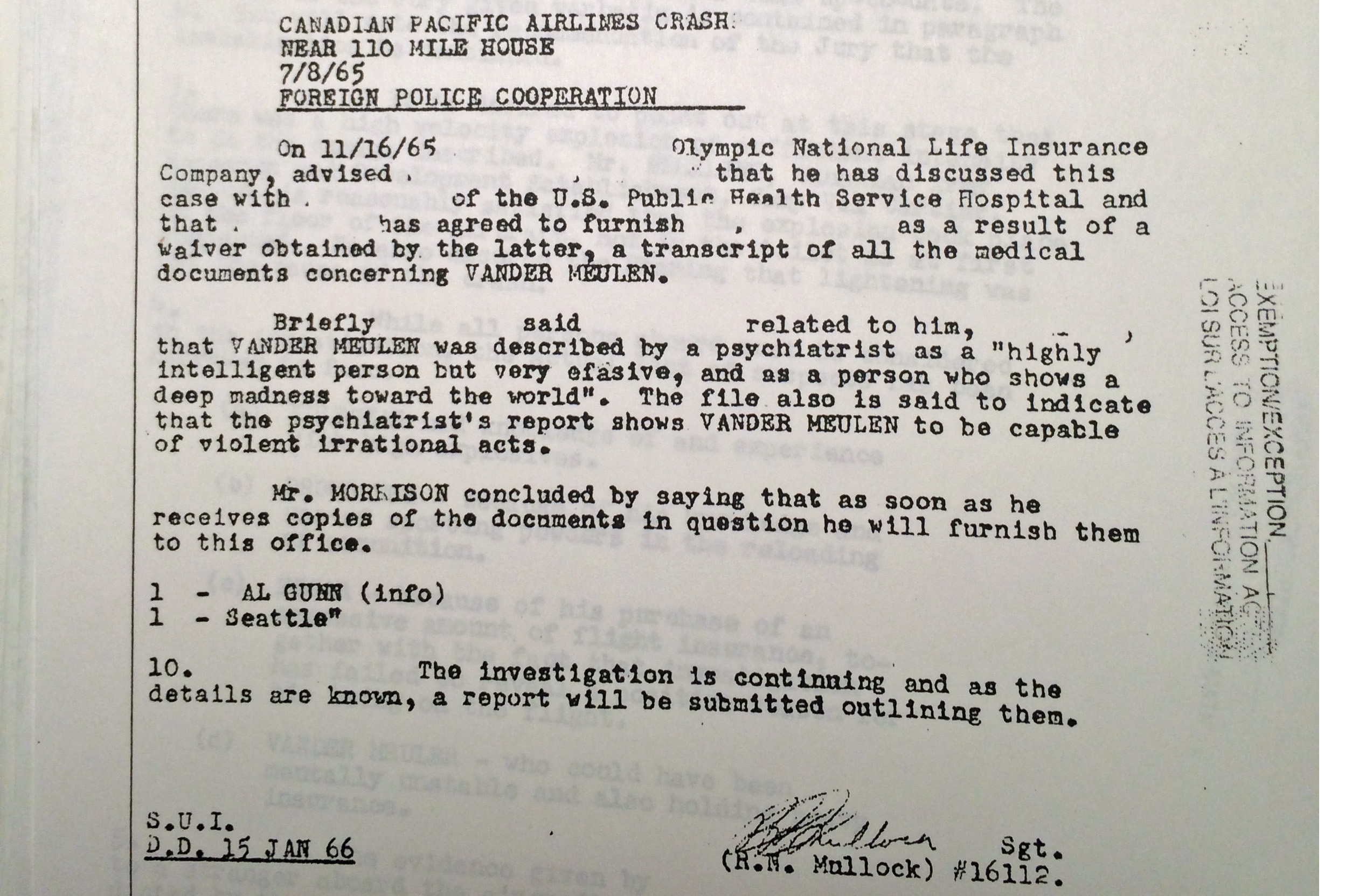

Vander Meulen's body was one of those x-rayed by the RCMP. They found copper fragments embedded in him, which were foreign to the aircraft. Copper is, however, used in blasting caps.

While this indicates that Vander Meulen was likely close to the bomb detonated in the rear lavatory, there is no way to know why. CBC discovered there was no assigned seating on these flights in 1965, so he may have just been sitting in the back of the aircraft when the device exploded.

The official investigation reports note that Vander Meulen had a .44 Magnum revolver on the plane, which he had registered with police.

His business partner also claimed he'd been carrying approximately $800 in cash — $400 of his own money and $400 in an envelope that belonged to someone else. It was an unusually large amount that's equivalent to nearly $6,500 in today's dollars when adjusted for inflation.

This money was never found at the scene.

They also write that two months before boarding CP 21, he purchased a large life insurance policy worth $100,000 (equivalent to $800,000 today). Due to a previous head injury, which he'd suffered while working on a boat, he had to pay a large premium of $800 (about $6,500 in 2018 dollars).

According to a police interviews, Vander Meulen told the agent he bought the insurance because he was going prospecting in the bush and wanted to take care of his family should anything happen.

After learning about this head injury, police dug deeper into Vander Meulen’s medical history, including psychiatric reports.

They discovered that a year before the crash, Vander Meulen was being seen by a psychiatrist and was diagnosed with chronic anxiety. In March 1964, he was deemed "unable to resume his usual occupation."

Vander Meulen was "capable of violent, irrational acts."

In a separate note, Vander Meulen is described by a psychiatrist as "a highly intelligent person but very efasive [sic], and a person who shows a deep madness toward the world." He added that the man could be "capable of violent, irrational acts."

"That sentence jumps out," says Woodworth, the forensic psychologist.

“Going down the list of motives that [are] possible — like notoriety, infamy, and financial — you start to get into mental state. If we are looking at the main kind of factors that rise to the top ... anger and resentment are potential motivators."

The fact that Vander Meulen's psychiatrist made the observations before the crash, when he thought the note would be private, makes it even more significant, Woodworth says.

Woodworth was also struck by the fact that Vander Meulen had bought insurance just a couple months prior to the flight, and had taken a gun on the plane.

While a gun and ammunition belonging to Vander Meulen were recovered at the scene of the crash, police couldn't determine whether he had these things on his person at the time of the bombing or if they were in his luggage out of reach.

"Anybody that would have something that would work effectively for crowd control, or to inhibit people's ability to stop them in that goal [of detonating a bomb], would be of interest," Woodworth says.

Arntfield, on the other hand, doesn’t buy it.

"If you're going to kill yourself, why are you carrying money … the same things that make him suspicious and mysterious are actually exculpatory."

CBC News searched for relatives of Peter Vander Meulen and was able to locate Sarah Taylor, his great-granddaughter from his first marriage, as well as Rene Roe, his step-daughter from his second marriage.

Rene Roe only knew Vander Meulen for a short time, but says he was good to her mother and that his death had a deep impact on her. "She just went into a tailspin. And it was, for the rest of her life, it was horrible."

Sarah Taylor wasn’t yet born when Vander Meulen died, but she recalls a story she was told by her grandmother, who was Vander Meulen’s daughter from his first wife.

"We were going over some of the family history, and she brought up that her father had died in a plane crash — and that her mother told her that she suspected he's the one who caused it," Sarah says. "But she told me she didn't agree with that, and she didn't know why her mom would say something like that, and that it upset her that her mom said that."

The likeliest suspects

Modern experts who helped analyze the CP Flight 21 case told CBC News that the original investigation into the crash appeared thorough and complete, with no apparent stones left unturned.

Nevertheless, investigators in 1965 never found the evidence needed to prove which of the four suspects, if any of them, planted the bomb.

The passage of time, the death of witnesses and the limited sources of information that remain mean the chances of discovering any new physical evidence are slim. And after reviewing the case, CBC and its experts also found no clear proof of who committed this crime.

However, when it comes to looking at means, motive, and opportunity, the experts CBC spoke with say it's possible to use modern profiling techniques to re-evaluate which suspects tick more boxes than others.

In the case of Douglas Edgar, as the investigators from 1965 point out themselves, the main reason they suspected him was the insurance he bought before boarding the plane.

Police never found any evidence of debts, and criminologist Mike Arntfield argues that pure altruism on its own is unlikely to be a motive to commit mass murder-suicide.

"This is a classic case of police tunnel vision."

"This is a classic case of police tunnel vision," Arntfield says. "They thought it was a financial motive, and clung to that theory. I think we can take him off the table entirely."

As for Stefan Koleszar, while he did have knowledge of explosives, Smith and his team showed that any adult could have procured the necessary bomb-making materials at the time, and building a bomb like the one that downed CP 21 didn't take much expertise.

Police never came up with a plausible motive for Koleszar.

Plus, the crimes he had been charged with in the past were very different from what was committed on CP 21. Arntfield and Woodworth both agree that his age does not fit the profile of a mass murderer, based on what we know about this type of criminal today.

"We have no known motive. Here's a guy who's got kids. He's got a good job. He's respected at work," Arntfield says.

That leaves Paul Vander Meulen and Peter Broughton.

However, when it comes to which one should be considered the prime suspect, there is a difference of opinion among the experts.

"You have to see which one forms the most complete picture," says Woodworth.

For him, based on the information available, that picture points to Vander Meulen, who was described as having a "deep madness toward the world" by his psychiatrist.

"He's the best suspect from more of a pathology perspective, and he is the same one that took out the insurance," says Woodworth.

On the other hand, Arntfield feels that it’s Broughton who cannot be eliminated.

"He has access to gunpowder, he has access to dynamite," says Arntfield.

And while this may not be enough on its own, he also argues that unlike the other suspects, Broughton, as a single man, had the privacy needed to devise a plan. Plus, at the Cassiar mine where he worked he might have been able to test an explosive without raising suspicion.

"Whether it's the Unabomber or the Columbine attackers, there was always a dress rehearsal."

"Whether it's the Unabomber or the Columbine attackers, there was always a dress rehearsal."

Arntfield also points to the descriptions of Broughton given by family and friends, and argues that certain aspect of Broughton’s personality, like being a loner, have also been seen in other mass-murder cases.

What the experts agree on is that 53 years after the bombing of CP 21, if we are ever to know who detonated the bomb and why they did it, new information is what will unlock the answer.

"It's down to what did people see in the weeks and months leading to this disaster," says Arntfield.

"Now that we have all this information, that could be that tipping point. Someone maybe holding the key to all of this."

Didi Henderson, whose father was killed in the crash along with 51 others, hopes someone who reads this story does come forward with new information that can finally bring the case to a close.

"I really hope that this may spark some new conversation and new discovery, and that we can really get the best picture of this story that we can," she says.

With files from Ian Hanomansing, Johanna Wagstaffe, Polly Leger and Ilina Ghosh

If you have any information to share about the bombing of Canadian Pacific Flight 21, phone our tip line for this case at 1-888-224-2949 or email uncover@cbc.ca.