June 21, 2019

The drumming of horse hooves grew louder, until it rivalled the howls and cheers from a riotous crowd that pushed a streetcar off its tracks and lit it on fire.

The horses — ridden by special constables and North-West Mounted Police — raced around the corner of Winnipeg’s iconic Portage and Main intersection, running toward the chaos five blocks north, in front of city hall.

Authorities collided with the crowd. Cheers became screams.

The blasts of gunfire rang out above it all.

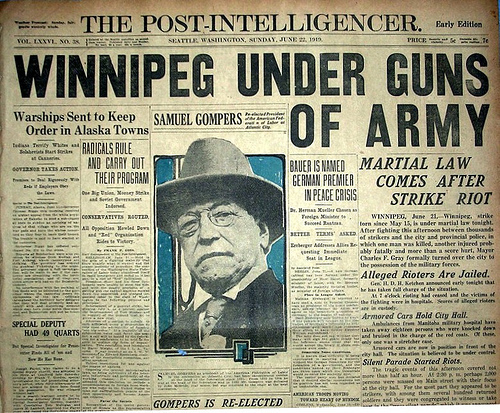

It was June 21, a defining day of the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike that became known as Bloody Saturday.

"There was mayhem like crazy. No other city in North America had seen anything like the violence and the fervour of the day," said George Siamandas, who maintains a website called Winnipeg Time Machine. "It would have been a maelstrom of unhappiness all around."

By June 21, the strike by tens of thousands of workers, which brought Winnipeg to a standstill and got the attention of labour, employers and politicians across the country, had been going on for six weeks.

The nighttime raids and arrests of labour leaders on June 16 and 17 were an aggressive move by the government to try to stamp out the strike by attacking it at the top.

It dealt a major blow to the labour movement, but also churned and agitated the deep rancour already flowing through the strike’s impassioned defenders.

To protest the arrests of their leaders, strike supporters planned a silent parade past city hall for June 21. The Central Strike Committee disapproved of the plan, choosing to back down from aggressive strike action, fearing further arrests.

The leaders, many of whom had been released on bail, agreed with the committee. However, they could not convince a core of enraged strikers and pro-strike soldiers, who met on the evening of June 20 at Market Square to announce the parade plans to others involved in the general walkout.

Mayor Charles Gray came out of city hall next to the square and warned them that civic authorities had "absolutely committed themselves to the breaking up of any demonstrations," adding that "any women taking part in a parade do so at their own risk."

"People's tempers get short, especially if you have leaders that can rile you up, and this happened on both sides," Siamandas said.

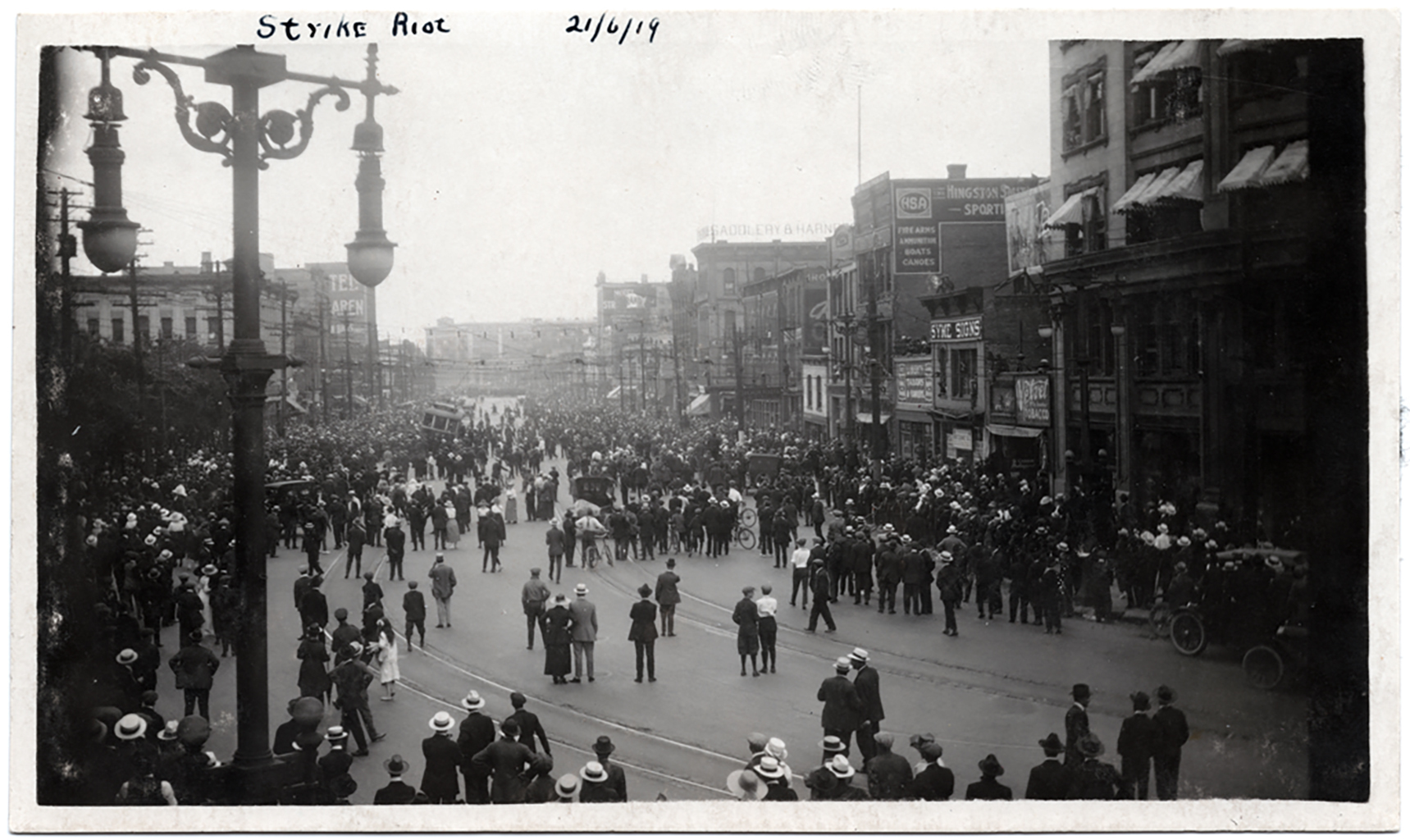

On June 21 at 2:30 p.m., a crowd began to form along Main, just north of Portage. Before long, it swelled to an estimated 6,000 as they headed toward city hall.

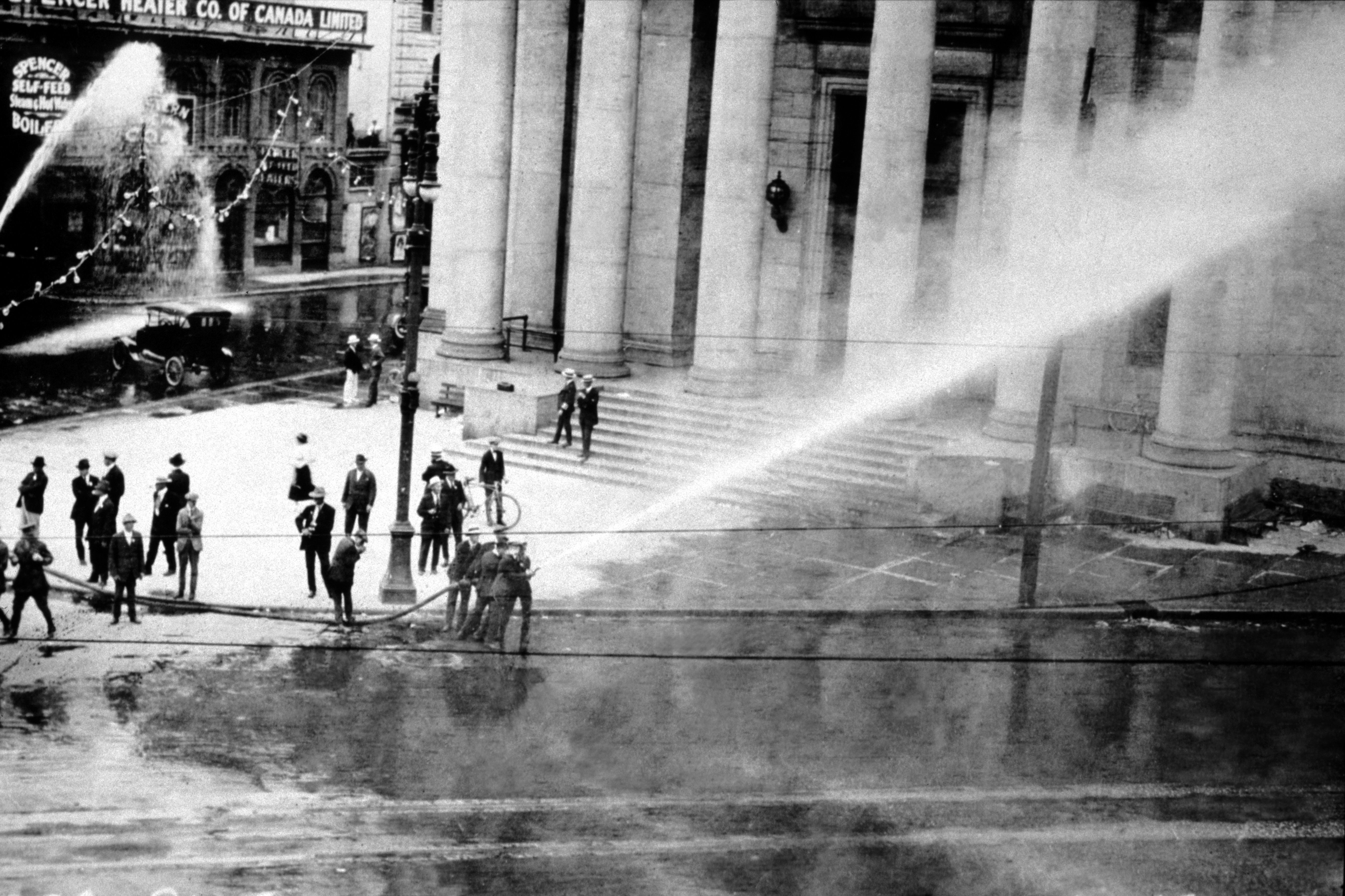

Gray read the Riot Act on the steps of city hall, ordering everyone to disperse, but to no avail.

Around the same time, a streetcar running along Main approached and was quickly surrounded and stopped by the crowd.

The car was being run by replacement workers, which the crowd took as an inflammatory attempt at breaking the strike.

They rocked the car from side to side but were unable to tip it over entirely. They smashed the windows, climbed inside, slashed the seats and set it on fire.

While that was happening, Gray drove to North-West Mounted Police headquarters to request emergency assistance.

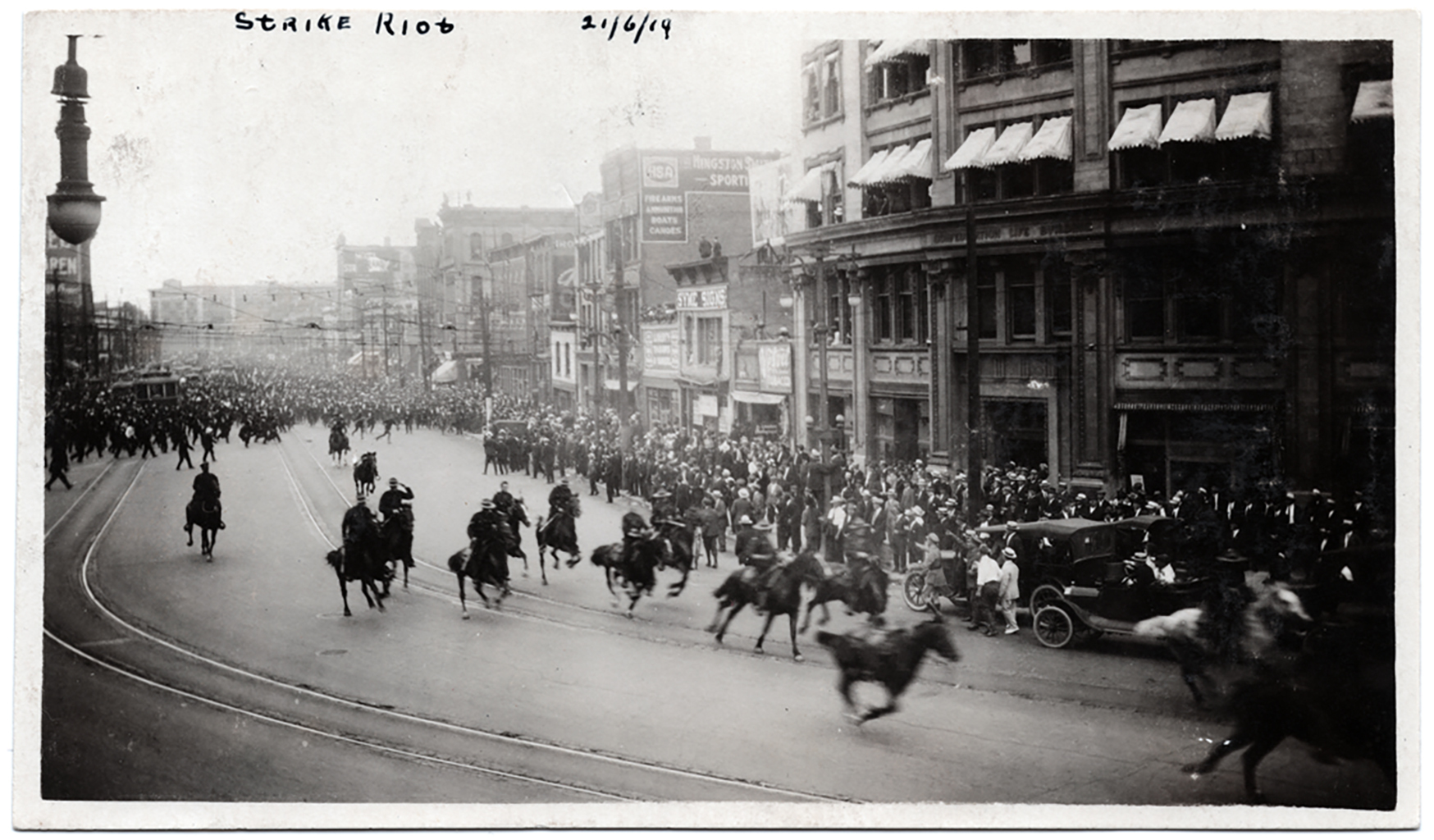

Within a short time, the mounted squad, joined by a number of special constables — hired after Winnipeg officers were fired for refusing to denounce the strike — lined up across the width of Main Street.

They loped into the crowd, knocking people down, forcing them off the street and onto sidewalks, and battered them with clubs if they didn’t move, according to multiple archival and contemporary reports.

After they passed city hall, they turned and made a second pass, swinging their wooden truncheons and moving closer to the people lining the curbs.

On the third pass, the crowd fought back. They threw rocks and bricks as the parade escalated into a riot.

The Mounties, in response, kicked the horses into a full gallop and charged.

They turned off Main and went directly into the crowd that had spilled onto William Avenue, alongside city hall. Several drew their pistols and fired into the mob.

Two bullets went through the legs of Steve Szczerbanowicz, who died two days later as a result of gangrene.

The police continued their charge, circling the block containing city hall.

From William, they turned onto King Street behind city hall and then up the other side along Market Avenue, which no longer exists on that side of Main.

Arriving back at Main Street, they fired again into the area around the smouldering streetcar.

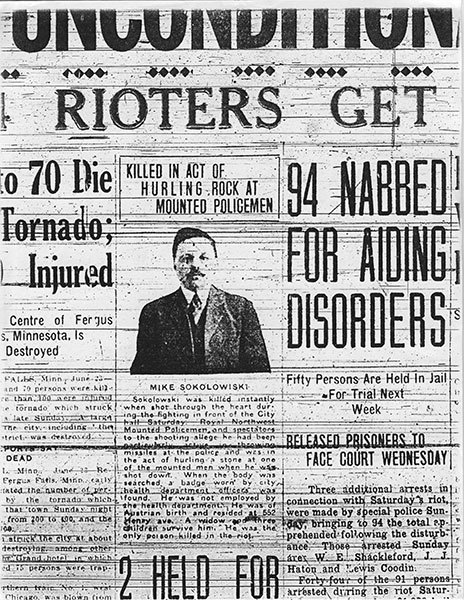

Mike Sokolowski, standing in front of Pantages Playhouse Theatre at the corner of Main and Market, dropped dead on the spot after being shot in the heart.

The mounted police and specials were joined by 200 club-wielding specials on foot, and strikers were corralled in a place later referred to as Hell’s Alley.

People in the crowd ran, but they were trapped in the alley between Market Avenue and James Avenue and beaten.

In that alley — where the Centennial Concert Hall now stands across from city hall — 27 people were injured in the shadow of the Winnipeg Labour Temple.

“They were just like thugs, beating people up,” historian Nolan Reilly said about the specials, remarking on "the brutality of it."

By 6 p.m., military personnel from Fort Osborne Barracks arrived, with bayonets on their rifles and machine guns mounted on the back of vehicles, and took control of the streets.

In all, it is estimated 45 people, both strikers and police, were hurt, and 94 people were arrested. The deaths of Szczerbanowicz and Sokolowski are the only ones directly linked to that day.

“[It was] a bloody mess, just putting it into a couple of words,” Siamandas said.

Winnipeg fell under brief military rule, one of the few occupations of a city in the history of the Canadian military, said Reilly, a former history professor who has written a booklet about the Winnipeg General Strike.

“It’s an example of the state — the Canadian government — turning its military and its police forces against its own citizens,” he said.

Bernice Fanning’s father, Fleming Parrott, was one of the returned First World War soldiers called to patrol the streets. She said he was behind a machine gun but was actually friends with some of those involved in the labour movement.

"They said if they were marching ... and he was behind the machine gun, they said, ‘Fleming, if you see us, don't shoot,’ and he laughed and laughed,” said Fanning, now 95.

"I said to him when he was telling that story, ‘What would you do if you had been ordered to shoot?’ He [said] he would never have fired at people and said, ‘I guess I would have shot into the air.'"

Authorities also shut down the strikers' newspaper, the Western Labour News, and arrested its editors, James Shaver (J.S.) Woodsworth and Fred Dixon.

The strikers could only muster a crowd of about 400 the following day at Victoria Park, where they mourned the dead and injured and the imminent end of the strike.

Hearing of the gathering, Gray closed the park and had the military stand by as the crowd filed out.

On June 25, the Central Strike Committee decided to end the strike. At 11 a.m. on June 26, it was officially over, and strikers were asked by the committee to return to work but to continue the fight in the political arena.

For many, there was no work to go back to, as some employers refused to rehire them.

Others had to reapply, losing seniority and starting over with entry-level wages — and they were rehired only after signing an anti-strike loyalty pledge.

Critics called the agreement the "slave pact." It remained a legal option for employers until city council rescinded it in 1930.

The 'Forgotten Immigrant'

Michael Sokolowski (whose name is spelled Sokolowiski in some accounts) was buried three days after Bloody Saturday, in an unmarked grave in Brookside Cemetery.

Little is known about him and his involvement in the riot.

The Winnipeg Tribune wrote that he was killed in the act of hurling a rock at police, and police and witnesses said he was "particularly active in throwing missiles" at officers and was struck down while in the process of throwing another.

Other reports have said he was just in the wrong place at the wrong time.

According to Winnipeg filmmaker and composer Danny Schur, who spent nearly a decade researching Sokolowski's story, Sokolowski was carrying a city health department officer's badge that had been stolen from the coat pocket of an inspector delicing a tenement building on Henry Avenue.

“For all we can tell, Sokolowski seemed to be a ne'er-do-well. He was definitely an itinerant labourer and he pinched that badge,” Schur said.

Sokolowski was also identified as a tinsmith of Austrian birth by some newspapers, reinforcing a common message from the anti-strike movement — that the strike was steered by foreigners.

A story in the Tribune listed his address at that tenement on Henry, and said Sokolowski left behind a wife and three children.

That’s true, said Schur, but no one showed up at Sokolowski's burial, and no relatives claimed his body from the funeral home.

"It’s tragic on two accounts," Schur said. "Either they didn't know that he was dead and he may have been buried before they knew it, or there could have been good reason to not show up.

"You have to remember, the authorities didn’t need much pretext to deport you."

Sokolowski’s story was representative of many people in Winnipeg at the time — non-unionized people who joined the strike at great personal risk.

"The record shows that half to two-thirds of participants were the Mike Sokolowskis of the world," Schur said. "So I was personally really taken with the fact that the guy at the epicentre [of June 21], the guy who pretty much died on the steps of city hall, was the most forgotten. It's just very heart-tugging."

Without any records to identify him, the coroner estimated Sokolowski's age at 40.

It took another 84 years before his unmarked grave was given a proper stone.

Through donations and volunteer efforts, including by Schur and the MayWorks Festival of Labour and the Arts, a headstone was created and set in place in 2003. Under Sokolowski's name, it says, "The Forgotten Immigrant," and includes a brief summary of the strike.

Striker E. Kornberger and brother J. Kornberger recall the Riot Act being read, describe Bloody Saturday and the army patrolling streets.

Steve Szczerbanowicz (alternately spelled as Scherbanyevich, Skezerbanovicz, Schezerbanowicz or Schezerbanowes) was similarly laid to rest in an unmarked grave, buried just over a week after Bloody Saturday.

Even less is known about him. A report in the Tribune says he lived in East Selkirk, but what he did for a living and what he was doing when he got shot at the June 21 riot is a mystery.

Through the efforts of members of the MayWorks board and two concerts held to raise funds, a gravestone was unveiled in 2015 for Szczerbanowicz — 96 years after his death.