April 7, 2018

Melisande Short-Colomb's dorm room at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., looks like any other. Textbooks and papers are scattered beside a laptop on the desk, while the windowsill is covered in touches of home — bright purple feathers, beads and wooden dolls from her native New Orleans.

The posters adorning her walls range from pretty paintings of flowers to political statements. The biggest one is of the famous moment of defiance at the 1968 Summer Olympics, when black U.S. athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists to the sky after receiving the gold and bronze medals, respectively.

For all the trappings of university living, Short-Colomb — who goes by Meli — is anything but a typical freshman. She’s a 63-year-old grandmother and retired chef sharing a floor with teenagers and 20-somethings.

Perched on a single bed topped with a puffy purple duvet, Short-Colomb reflects on being the oldest undergrad on campus.

"The kids, they move so fast," she jokes. "I was like, 'Oh my God, how can I keep up?' But I am."

Short-Colomb has no shortage of motivation. Coming to Washington, D.C., isn't only about the pursuit of a prestigious degree. It's also a mission to pay homage to her family's past — a past intertwined with Georgetown's own.

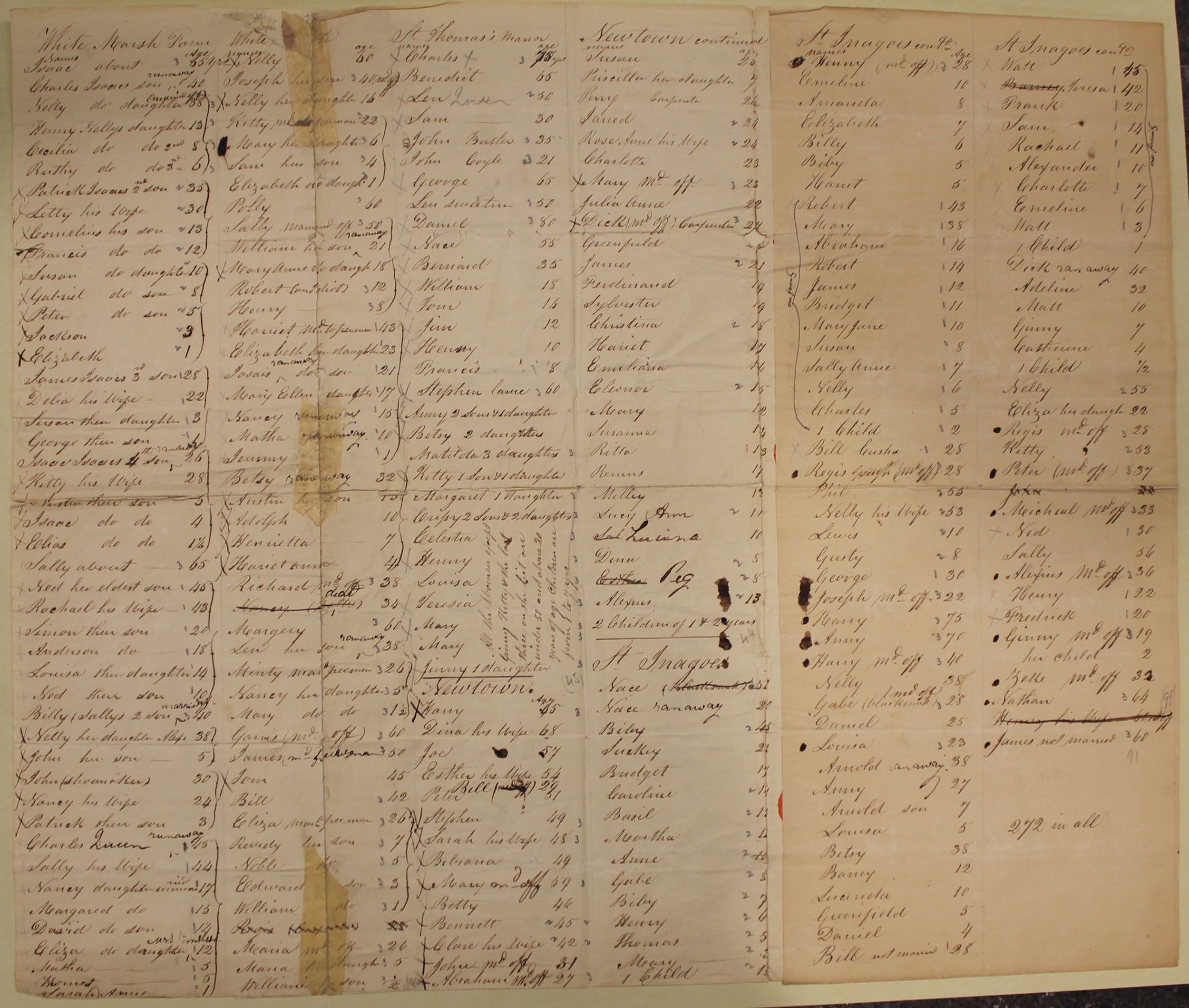

In 1838, in a bid to avoid bankruptcy, Jesuit priests who ran the university sold 272 slaves to plantation owners in Louisiana. The proceeds of the sale — the equivalent of $3.3 million US today — ended up saving what is now one of the country's most illustrious universities. But it also implicated it in one of the darkest chapters in U.S. history.

"They're sort of here with me. I feel whispers in my ears and pats on my back."

Among those slaves were two of Short-Colomb's ancestors: Abraham Mahoney and Mary Ellen Queen.

In the years before the sale, members of the Queen family in Maryland tried suing the Jesuits for their freedom. They were ultimately unsuccessful, and like the other 270 slaves, Short-Colomb’s ancestors were taken from Maryland, packed onto wooden vessels and shipped to the swamplands of Louisiana.

There, they would toil away on plantations for the rest of their lives. It was their descendants who would become free, long after the Civil War.

In 2016, Georgetown said it would offer preferential admission status to descendants of those sold, and it was the lure of that personal history that convinced Short-Colomb to apply to Georgetown.

"I'm very proud to be able to be here, in 2018, on this campus, to speak their names," she said of her ancestors. "They're sort of here with me. I feel whispers in my ears and pats on my back. I think they'd be very happy and very proud."

While Georgetown's offer of preferential admission helped Short-Colomb enter a new chapter in her life, there is a debate swirling over whether the university is doing enough to address the stain of slavery on its history.

How does an institution atone for having sold human beings?

II.

Georgetown University is named after the historic neighbourhood where it's located — the oldest enclave of Washington and arguably the most idyllic. Nestled on the Potomac River, Georgetown is known for its cobblestone streets, shaded sidewalks and quaint row houses dating back to the 18th century.

The oldest Catholic and Jesuit university in the U.S., Georgetown was founded in 1789. During the Civil War (1861-1865), the university was turned into a temporary hospital. At the war’s end, Georgetown made its school colours blue and grey to symbolize reconciliation between the Union and Confederate armies — colours that remain the school’s signature today.

Along with being one of the country's oldest universities, Georgetown is also one of its elite — alumni include former U.S. president Bill Clinton and journalist Maria Shriver as well as foreign royalty, including King Abdullah of Jordan and Spain's King Felipe.

Short-Colomb knew very little of Georgetown's storied past when her journey here began. Having returned from a six-month stint as an executive chef at a resort on the island of St. Croix, she was working as a chef instructor at a small concept restaurant in New Orleans in 2017 when she received a mysterious Facebook message.

"I felt a little anger. And I felt profound sadness."

The message was from Judy Riffel, a genealogist with the Georgetown Memory Project, a private organization unaffiliated with the university. It asked Short-Colomb whether she was related to a woman named Mary Ellen Queen. Riffel wrote that Queen was a slave sold by the Jesuit priests who ran Georgetown.

Short-Colomb was shocked. She had heard of the Georgetown sale in the past, but had no idea it involved her family.

"I felt a little anger," she said of her initial reaction. "And I felt profound sadness."

The revelation erased everything Short-Colomb thought she knew about her roots in the U.S. According to family lore, her ancestors from Maryland had been freed before the end of the Civil War and willingly travelled to Louisiana.

While she had accepted that narrative, the notion that freed blacks would travel south in that era never made much sense to her. But the truth seemed even harder to believe — that her ancestors had been sold south by the most prominent Jesuit order in the U.S. at the time.

"It's one thing to know people owned and sold my family," Short-Colomb said. "It's another to know who those people were, and that those people were the Society of Jesus. They were priests."

Religion did not preclude an active role in the slave trade. The Jesuits used slave labour to run a network of farms and plantations across Maryland and the profits, in turn, helped fund Georgetown.

Georgetown isn't the only university coming to grips with a slave-holding past. Many of the oldest and most elite universities in the U.S. have ties to the slave trade, even benefiting from it, including Yale, Harvard and Princeton.

"No college survives the colonial period without attaching itself somehow to the slave economy," said Craig Wilder, author of Ebony & Ivory: Race, Slavery and the Troubled History of America’s Universities. "We live with that legacy today."

III.

Maringouin is the word Cajuns use for mosquito. It's also the name of the town in Louisiana where the Georgetown slaves arrived in 1838.

It's a fitting moniker. Even in the winter months, heavy humidity hangs in the air. Bayous, with their resident alligators, ring the town's edges.

Jessica Tilson, 34, grew up here. Though the race-based Jim Crow laws had been officially abandoned decades before she was born, Tilson is no stranger to segregation — especially at church.

"Whites on one side, blacks on the other," she said, standing outside the town's small Catholic Church, Immaculate Heart of Mary. "The older people keep it going that way."

Like Short-Colomb, Tilson only recently found out about the 1838 sale and her connection to it. "We've been here for so long, we thought we were from Louisiana," she mused. "But lo and behold, we were from way up in Maryland!"

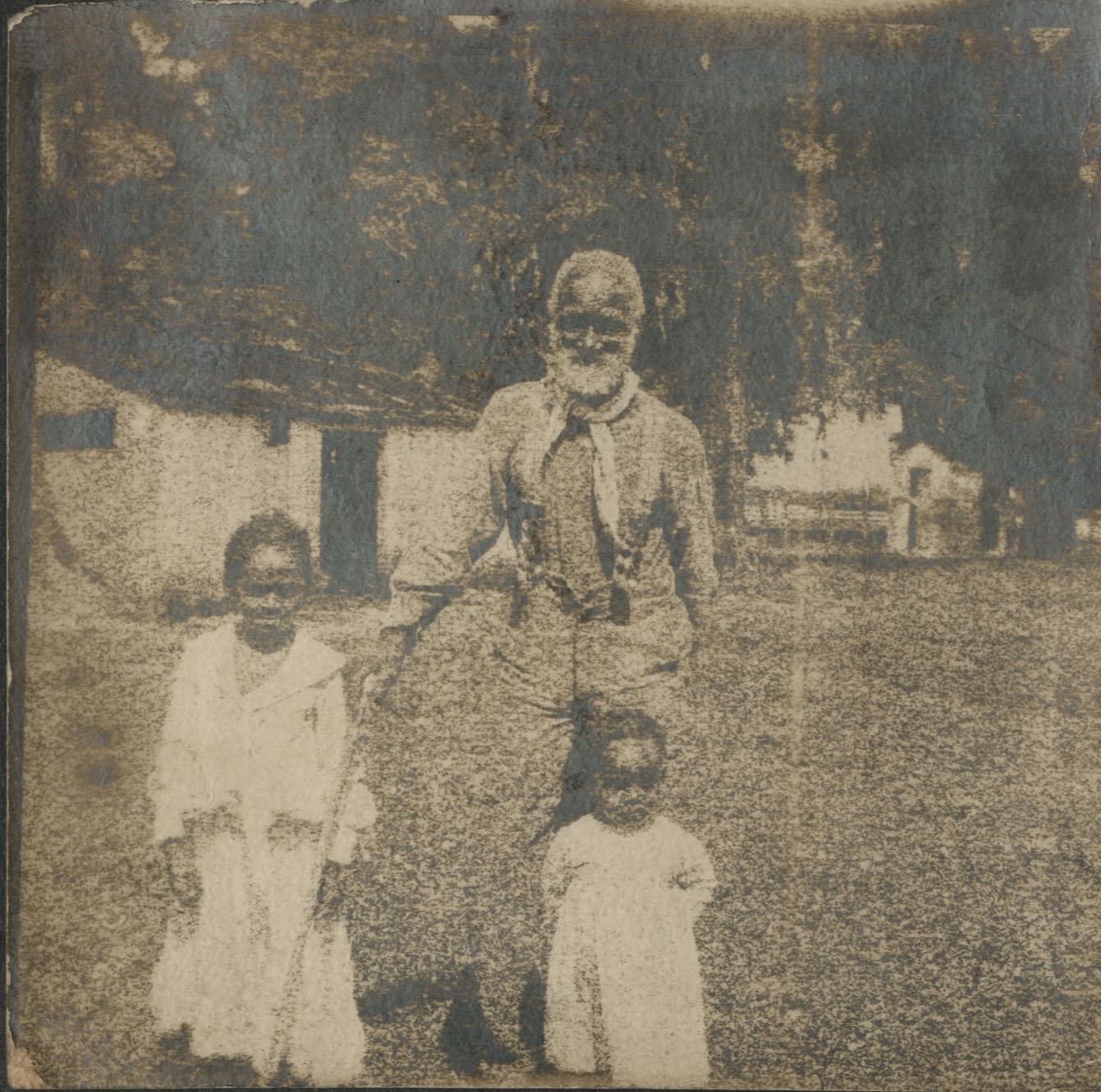

Maringouin is a small and poor place — 30 per cent of the town's 1,200 residents are below the poverty line. Almost everyone here is a direct descendant of those who were sold.

Tilson is a descendant of Isaac Hawkins, the first name on the 1838 bill of sale. She often comes to the local cemetery, bringing along her young daughters who help her clean the headstones and tombs while she tells them what precious little she knows about her ancestors.

"This is one of the 272," Tilson said, gesturing toward a faded headstone, one of few marking an actual burial. "A lot of them are buried here."

Every few months, Tilson welcomes groups of students from Georgetown. As part of its efforts to recognize the past, the university sponsors visits to the town to show students the other side of the sale.

"These were people, they had lives and I want to tell their story for them because they can't speak for themselves," Tilson said. "Stories like this are important because it actually tells the history of America."

Tilson takes the students to a lookout so they can see the sprawling fields where her ancestors were enslaved. There’s seemingly no end to the wide open space. And for the slaves, there would have been no escape, with their masters' homes on one side of the field and swamps on the other.

All the while, they laboured in an oppressive climate they had never experienced before.

"It's so hard to imagine," Tilson reflected as she stared over the fields. "They wouldn't have known anything about this place."

Tilson herself may have had an entirely different life had the sale never happened, but she holds no bitterness towards the university. All she wants is for the school to continue to acknowledge its past by maintaining — and further growing — it's relationship with Maringouin.

"To me, they’re doing what they can do," she said. "You just have to accept that my ancestors are gone, they sold them. They can't reverse the sale. That would be the thing I'd want, but they can't. It's a catch-22."

IV.

Like Short-Colomb, Tilson learned about the sale from the Georgetown Memory Project. It's a work of passion run by a Massachusetts businessman and Georgetown alumnus named Richard Cellini. The GMP is run through donations and, when they're not enough, out of Cellini’s own pocket.

Cellini founded it in the winter of 2015, after an unnamed university official told him that all of the Georgetown slaves became ill and died after arriving in Louisiana.

"I didn't really believe that could be true," he said. "My question became what happened to those people, the 272 who were sold."

Cellini hired a small group of genealogists to pore over centuries-old records to track down the descendants. So far, they've managed to contact more than 6,000 people.

It may seem odd that an individual would take this responsibility on himself, but Cellini said he was driven by the Jesuit philosophy of "magis," the concept of doing more.

"I love Georgetown deeply," an emotional Cellini said. "If you love Georgetown, you must love the families who involuntarily sacrificed to create it."

In the fall of 2015, Georgetown began to officially atone for the first time. It established the Working Group on Slavery, Memory and Reconciliation, tasked with determining how the university could right the wrongs of history.

Based on the group's recommendations, university officials promised to do more outreach to the descendant community and continue to further the study of the school’s slaveholding past. The university's president, John DeGioia, travelled to meet descendants, which included a trip to Maringouin in 2016.

In 2017, Georgetown renamed two buildings on campus — one in honour of Isaac Hawkins and another after Anne Marie Becraft, a free woman of colour who founded a school for black girls in Georgetown in 1827.

The buildings had previously been named after Rev. Thomas Mulledy, the former president of the school who arranged the sale, and Rev. William McSherry, who helped Mulledy broker the deal. Students staged sit-ins outside DeGioia’s office to push for the name changes.

"Talking about the past is always a way of talking about the present," said author Craig Wilder. "Students have been effective at weaponizing history to highlight the injustices and problems happening in our society today."

In April 2017, the school invited more than 100 descendants, including Short-Colomb and Tilson, to what it dubbed a Liturgy of Remembrance, Contrition and Hope. There, DeGioia and Rev. Timothy Kesicki, president of the Jesuit Conference of Canada and the United States, formally apologized for the sale.

"Today, the Society of Jesus, who helped to establish Georgetown University and whose leaders enslaved and mercilessly sold your ancestors, stands before you to say that we have greatly sinned," Kesicki told the crowd.

The school also announced that it would offer legacy status to descendants, meaning that any descendants applying to the school will be given preference over other students, so long as they meet academic requirements. It's the same status given to the children of Georgetown alumni and others affiliated with the university.

At home in New Orleans, Short-Colomb saw the offer as something of a dare.

“Someone had to be the first to come, to start this chapter, to push the university to actually follow through on this,” she said. Despite it being an unconventional move for someone her age, no one doubted her, she said.

"Everyone just told me, 'You got this.'"

But legacy status does not include specific scholarships for the descendants. Short-Colomb's tuition and housing is paid for through a combination of a needs-based scholarship, a work-study program that sees her put in a few days a week at the school library and good old-fashioned loans.

"I'm here on a scholarship program that already existed," she said. "The university needs to do more. And it wants to do more. The question is just figuring out what exactly that 'more' should be."

V.

For some descendants, that “more” should be financial reparations.

"It brings out so many emotions in me: sadness, anger, devastation," said Dee Taylor, another descendant of Isaac Hawkins, who lives in Baton Rouge, La., not far from Maringouin. Taylor said she's often haunted by thoughts of what happened to her ancestors.

She appreciates what the university has done so far, but she said it's not enough to right the wrongs of the past. "It will be a more restful night for me when the period is put at the end of this journey."

Taylor is part of the GU 272 Isaac Hawkins Legacy, a group of around 200 members who’ve launched a campaign calling on the university to pay reparations to the descendants. They argue that since Georgetown’s survival and eventual status as a world-class university hinged on the sale of their relatives, financial restitution is the only way to make it right.

The group's lawyer, Georgia Goslee, said it has presented Georgetown with an undisclosed amount as a suggested payment, but the university has yet to respond.

"There could never be an amount that's adequate for this pain and suffering," she said. "But financial compensation is all they can do to remedy this."

Neither Georgetown nor the Jesuits have any current plans to pay reparations. University officials say they'll continue to focus on their outreach and dialogue with the descendant community as a way of creating partnership and reconciliation in the future.

There's one key to achieving that, said Georgetown professor Adam Rothman.

"The school might not exist if not for those people, so I think that's an important focus for those of us at Georgetown."

"The way towards that goal of acknowledgement and reconciliation is to never think enough is being done. I always want to see more. The school might not exist if not for those people, so I think that's an important focus for those of us at Georgetown."

Rothman was on the school's working group and now runs the Slavery Archive at Georgetown, a treasure trove of documents relating to its slaveholding past. He has shown them to dozens of descendants who’ve come to the school wanting to learn more about their ancestors — including Short-Colomb and Tilson.

He said that the school's relationship with Maringouin is key to ensure the past is never forgotten.

"I want to see more students understand the history," he said. "I just want to see it keep rippling out to touch more and more people."

That's part of the reason Short-Colomb wanted to come to Georgetown.

"I was born in the South, raised in the South, I have always been at peace with who I am and the history of America," she said. "I wanted to continue opening our dialogue, our perception and our country to being more inclusive."

She thinks about the history that brought her to Georgetown every day, but the challenges of being a student, as well as a mother and grandmother, far away from home and family take up most of her time.

"I get homesick sometimes," she said. "But then we have the luxury of living in a time when keeping in touch is not a hard thing to do."

The most immediate issue for Short-Colomb right now is making a final decision on her major. She's leaning towards history.

"You're never too old to learn new things," she said. "And to find out everything you've been told has been wrong."