November 29, 2020

He'd travelled more than 3,000 kilometres from Jamaica to southern Ontario to work on a fourth-generation family farm growing everything from asparagus to watermelons.

He was braced for the hard work, the long hours and the loneliness. After all, this was his seventh season coming to Canada to provide for his four-year-old son and his extended family back home. But nothing prepared him for this season, and how the COVID-19 pandemic would change his life on the farm.

"Honestly, it feels like I am in prison."

The worker, whom we are calling Ben, has asked The Fifth Estate to protect his identity to help his chances of coming back to work on a farm in Canada next season.

Like all seasonal workers, Ben was taking a chance coming to Canada. While numbers of COVID-19 cases were relatively low in Jamaica, they were exploding here. What Ben didn’t know was that he would become one of the voices speaking out against the weaknesses others have long seen in the country’s seasonal agricultural program.

"The pandemic has made more obvious things that we've already known for years and years. It's shone a spotlight on the vulnerabilities of the system," said Rod MacRae, a food policy researcher and professor at York University in Toronto.

WATCH | A food policy expert explains cracks in the farm worker program:

Many workers, he said, have dire circumstances at home. Work can be hard to find, and in recent years, natural disasters have wiped out families’ homes.

"The money they receive here is substantially higher than they might receive at home. Or they might not have any work at home so they'll suffer the consequences of the wider conditions in order to get that wage."

- WATCH Bitter harvest on The Fifth Estate on Monday at 9 p.m. on CBC-TV and Gem

Because of the rules under which Ben is working in Canada — and which "everybody is criticizing," MacRae said, the migrant worker is like a “captive worker” without many options.

Ben said from his arrival last spring, his employers, Komienski Ltd. in Norfolk County, essentially told the farm’s dozens of migrant workers that they must stay on the farm or in their bunkhouses at all times to limit the chances of them contracting the novel coronavirus.

"We are allowed out two to three hours every two weeks." Ben said. "Only on our shopping days to get our food, that's the only time we can leave. If we leave and he sees us leaving, anything like that, then the first thing he would want [is] to send us home."

Ben is one of tens of thousands of farm workers who travel to Canada as part of the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program, also known as SAWP. It is an annual migration of people from Mexico and the Caribbean for up to eight months to plant, pick and pack $5 billion worth of produce, and provide a labour lifeline for Canadian fruit and vegetable farms.

The federal government lifted travel restrictions in March to allow workers into the country, but many say their living and working conditions have worsened this season.

Critics of the program that brings them here say the workers are in a more vulnerable position than ever. In addition to poor living conditions and low wages, these circumstances have heightened tensions among workers, and also between the workers and the communities where they work and live.

"There might be 10 or 12 people in a bunkhouse — half of them are going to say: 'We want to go out' and the other half are going to say: 'If you're going out, you're going to bring COVID back in,'" said Norfolk County activist Leanne Arnal, who has been selling clothes to workers for more than 10 years.

"There’s been deep-rooted systemic problems within the farm working community historically," she said, but COVID-19 has shone a light on negative attitudes towards workers, poor living conditions and workers' rights.

Arnal can't understand how some Canadians vilify them for being here when they are such an essential part of our food system. Some farmers, she said, were adamant that workers not leave the farm this season.

Ben said when he arrived in April, it was made clear to him by the farm owner that he and the other workers were not allowed to leave the farm unless they were supervised.

"He's saying that we are going to put his farm at risk of spreading COVID. But at the same time, that rule is not applied for the Canadian workers…. they can leave, go home … they can go wherever they want. They interact with whomever they want, but we can't do it. That rule doesn't apply for them. Only for us."

And that is a pandemic paradox. Migrant farm workers are seen as essential to Canada's food security. And yet, according to research done by The Fifth Estate, migrant farm workers in Ontario contracted COVID-19 at a rate 10 times higher than all other people in Ontario. The question then, is why?

II.

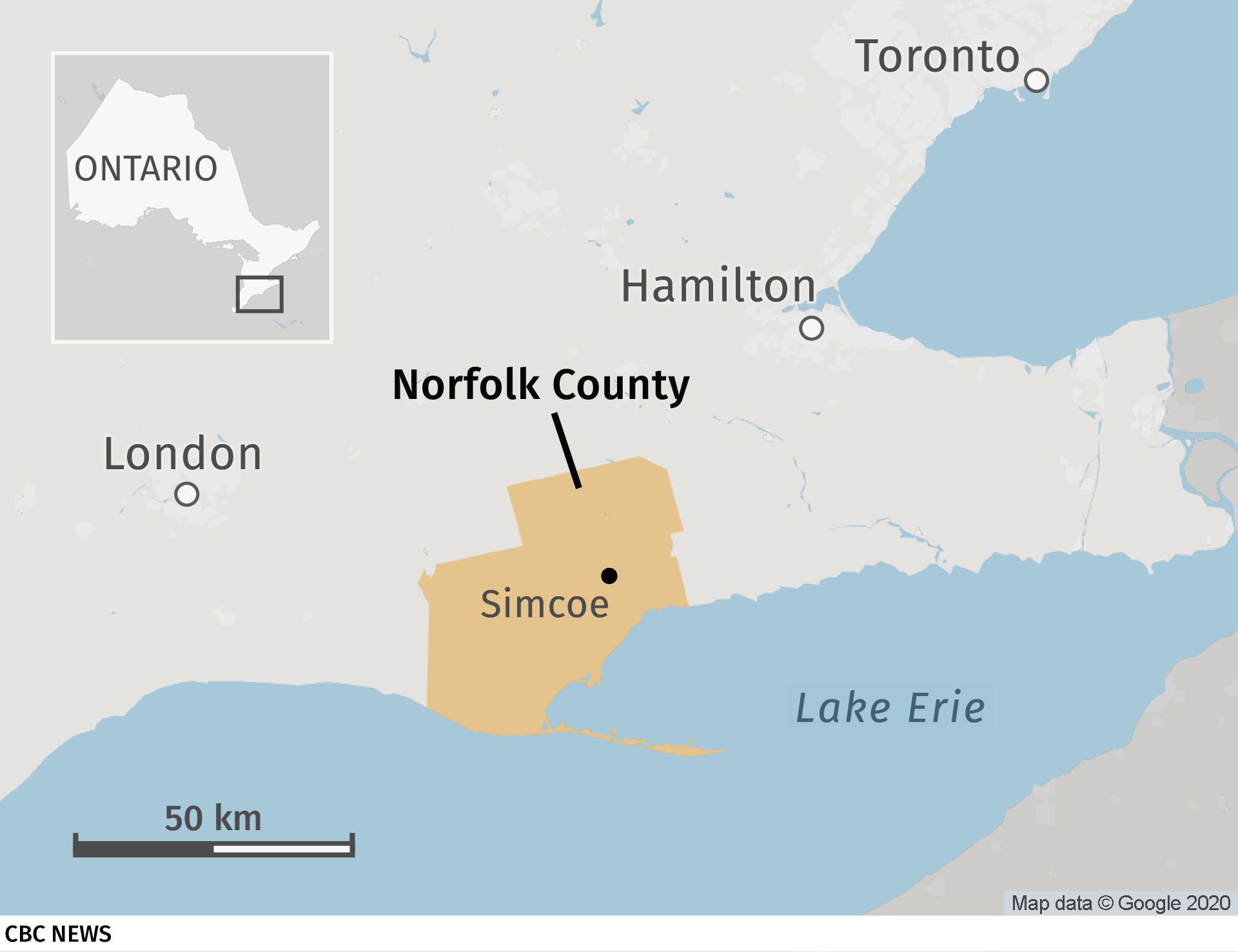

Southwestern Ontario’s Norfolk County, known as "Ontario’s Garden," is one of the leading agricultural regions in the country. It supplies fruits and vegetables across Canada and into the U.S.

Because this type of agriculture is labour-intensive, Norfolk County has one of the highest populations of migrant workers in Canada. The local population can increase by as much as 10 per cent during the season. In a typical year, more than 6,000 people travel to work on farms in the county.

"Without them," said Norfolk County Mayor Kristal Chopp, "agriculture here wouldn’t survive. They’re essential to ensuring the continuity of our food supply chain."

As part of the deal to tap into a reliable migrant workforce, farmers must provide housing and access to necessities such as groceries and health care. The pandemic has added weight to these responsibilities — keeping the workplace free of COVID-19.

"The whole thing's unknown," said Danny Procyk, co-owner of Procyk Farms Ltd. "So it's up to the farmer, in a way, to make the best decision for their employees."

Not everyone agrees with the decisions farmers are making.

Ben, from Komienski Ltd., said in years past, "you could go [into town], sit, have a drink, talk to your friends or family if you have them here. And this year you can't do that."

It's a harsh reality. He has limited movement off the farm for grocery shopping, and he can be expected to work up to 17 hours a day. He could also be asked to work six or seven days a week.

For that work, Ben earns $14.25 an hour, Ontario’s minimum wage. Under Ontario law, he isn’t entitled to daily and weekly limits on hours of work, daily rest periods, time off between shifts, meal breaks or overtime pay.

Farm workers — whether they are Canadians or migrants — are not covered by many of the basic labour protections afforded to other workers in Ontario.

WATCH | Quitting time after a long day harvesting tomatoes:

"Farmers consider themselves special," said Emily Reid-Musson, a geographer and post-doctoral researcher at Memorial University of Newfoundland. "And I'm not sure that it would destroy agriculture to just meet basic workplace regulations, like having to pay workers holiday pay or overtime pay, the way you would in retail, for example."

And the federal program that brings migrant workers to Canada is built on those rules.

III.

Last year, the federal government reported that nearly 50,000 seasonal workers left their homes and families to work on Canadian farms. That's one of the highest numbers since the creation of the agricultural worker program. With the pandemic, the number of workers travelling to Canada this season was cut by nearly half.

When it was founded in 1966, the program saw 264 workers arrive from Jamaica to work mainly in apple orchards.

Brett Schuyler, co-owner of Schuyler Farms Ltd. in Norfolk County, said apple farmers pushed for the program because they needed a reliable workforce available when the crops needed to be harvested. He said student workers returned to school in September, just at the moment the fruit was ready to be picked.

The program is a huge benefit to farmers for this reason, but it comes with financial obligations.

"One of the myths of the system [is] that it's really cheap to bring in these workers. Most farmers have to pay not only the wage bill but they have to pay for their housing. Sometimes they're paying for food. They often have to pay for their transport," said MacRae.

The SAWP is based on bilateral agreements between Canada and the workers’ home countries in the Caribbean and Mexico.

The program allows Canadian farmers to recruit the workers they want to hire and retain them by limiting job transfers between farms. It’s difficult under the program for workers to quit a job on one farm and move to another. Farmers can also send workers home mid-season if they are unhappy with their performance.

Inherently, the program creates a relationship of imbalance between the farmer and worker, MacRae said.

"The rules are basically stacked against the farm workers."

IV.

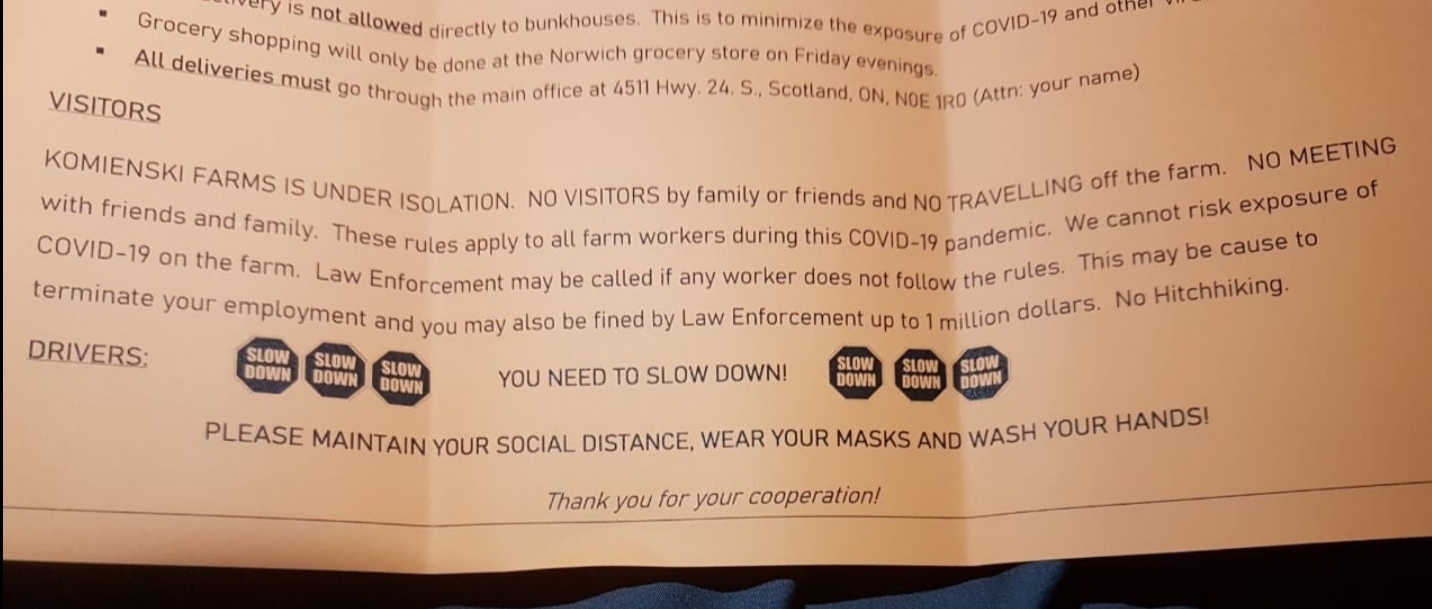

Although federal law prohibits employers from holding migrant workers on the farm, the only time Ben could leave the Komienski farm after arriving in April was every other week on an escorted grocery store trip.

He provided a photo to The Fifth Estate of a notice he said the workers received from their employer.

The notice said: "No travelling off the farm," in a bid to minimize the risk of exposure to the virus. "Law enforcement may be called if any worker does not follow the rules."

The warning to workers says if they do leave the farm without permission, it "may be cause to terminate your employment," and "you may also be fined by law enforcement up to $1 million."

Under the federal Quarantine Act, there is potential for a fine of up to $1 million for breaking isolation. However, this only applies to the two-week period after a person arrives from outside Canada, which can be extended if they develop symptoms.

On Aug. 29, farmers received an email signed by the federal director general of the temporary foreign worker (TFW) program. "The TFW program does not provide employers with the right to limit the free movement of workers, such as movement off the property where TFWs live and/or work," said the email obtained by The Fifth Estate.

When The Fifth Estate spoke with Ben in October, several weeks after the federal government sent the email to farmers, nothing had changed on his farm.

Komienski Ltd. declined an interview with The Fifth Estate.

Ben is one of a chorus of migrant farm workers across Canada complaining they were denied freedom of movement. These complaints ramped up in July and August, as the first wave of COVID-19 receded and the rest of the country was allowed back into bars and restaurants or to work out at the gym.

Procyk Farms Ltd., one of the biggest vegetable growers in Norfolk County, and a supplier to Loblaw Inc., also took measures to lock down their farm. They employ at least 550 workers, mostly from Mexico.

Back in March and April, workers were going into town, but the Procyks put an end to workers' weekly grocery trips and set up their own online store, allowing the staff to order a broad range of food items that they could pick up — and pay for — right on the farm.

"In the beginning … they loved the idea. They couldn't believe what we were doing," said company president Paul Procyk. "They just enjoyed the whole idea that they didn't have to … rush to town and wait in line and … go against the local people to get their groceries and do their stuff."

For Procyk’s family, who grow everything from corn to tomatoes, peppers and zucchini, the financial loss of having to close from an outbreak would be tremendous.

"We do 75 million pounds of produce here a year. In a matter of, let's call it 14 weeks. Take two of them away, that pretty much tells you what it is. Right? It's huge…. At the end of the day, we're feeding people. What's wrong with that? Are you really worried about ... how it gets done?"

But Procyk acknowledged there’s no way everybody was happy with the decision to urge workers not to leave the farm.

He said farmers struggled this year because of different directions from three levels of government: the county’s health unit, the province and the federal government.

"There's just too many groups that think they are telling us how to do what's best for the workers."

Arnal said migrant workers felt the brunt of the COVID-19 fears in the community this season.

"There's been racial profiling and confusion around isolation and at the end of the day the community has lashed out at the farm workers and treated them as though they are a risk when in fact they are at risk just like the rest of us," she said.

Chopp, the Norfolk County mayor, said that at one point "we were receiving emails that how dare we allow the migrants to wander around town, to go to the grocery store."

Workers and their employers felt targeted by the mixed messages.

"You're the bad guy if you send them to town, you're the bad guy if you keep them [on the farm]," Danny Procyk said.

About a dozen other farms in Norfolk County were accused of restricting the movement of their workers this season, including Komienski Ltd. The complaints were forwarded by worker advocates to the local health authority and passed on to officials at the Ontario Ministry of Labour and Employment and Social Development Canada.

Chopp said once workers have gone through the mandatory two-week quarantine after arriving in Canada, they should be treated like any other Canadian.

"We've heard of the complaints, we've called the Ministry of Labour, we've gotten them involved in a couple of farms where we've heard of farmers not allowing their workers to leave," Chopp said.

It is not clear what, if anything, was done in response to the complaints from Norfolk County. In an emailed statement to The Fifth Estate, the Ontario Labour Ministry said that at the end of July, it received a list of farms alleged to be locking down workers in Norfolk County but said such allegations “are not in the jurisdiction” of the ministry.

For its part, the federal employment department did not specify whether it took actions at any farms beyond sending the email to farmers in late August regarding the regulations under the temporary worker program that prohibit restrictions on employees’ movements.

Chopp said the majority of Norfolk's farms did not restrict workers' movements but was surprised when told about Komienski Ltd.

Locking down workers, she said, is "against our own human rights laws" in Canada. "This issue with migrant workers, this I would say is the civil rights issue here of our time. Without a doubt."

Brett Schuyler is one of those who didn't restrict workers' movements. He employs about 250 migrant workers on his rolling apple orchards near the town of Simcoe.

"I've got a lot of respect for the workers on this farm. I haven't been out to these farms where this is happening," Schuyler said. "When your farm is run by this group of migrant farm workers, they can't be pissed off with you, they can't be thinking ill of you. It's a team, it's a family."

V.

Timothy Frederick, who is from Trinidad, has been working for Schuyler for about six years and has come to learn all about apples. Crispins, he said, are so delicate the fruit should be handled like an egg.

He tries to stay positive. But because of the pandemic, he lost thousands of dollars of wages while waiting months in Trinidad for his government to approve his departure — and that of hundreds of other workers.

To top it off, the two-week mandatory quarantine was hard to take.

“It sucks."

Still, said, he's giving the shortened season his 100 per cent.

As he was working in Schuyler's orchard, Frederick smiled at a friend one tree over. She, too, was grinning as they joked around.

This is Shelly Ragoo’s first season working in Canada. Her sister, Sheerine King, is here for the first time as well. They both left children and family behind in Trinidad to make what they call an "honest wage." Much-needed work is hard to find back home.

But also behind their smiles is their brother, uncle and father. Felix Ragoo has been coming to Canada for 23 years under the SAWP program, 21 of those years on Schuyler's farm.

"It is nice now to see that I have my two daughters, my son and my brother-in-law here with me to keep me company."

But not all workers are getting that family feeling.

When Clinton John arrived at a Norfolk County farm in May 2019, he was shocked to find he would be living in a furnished garage with two other workers from Trinidad.

The garage didn’t have a stove, heat or running water. The toilet was a porta-potty. It was one room, with chairs, beds and hanging sheets for privacy.

"I wanted to come to Canada to work to maintain my family, to get a better life, to achieve certain things that I knew I could achieve by working hard to get it," John said.

He didn't bargain on living in a garage.

John shot a video of the garage on his phone and posted it later on social media. He said one of the owners, Darryl Zamecnik of EZ Grow Farms Ltd., promised he would build new bunkhouses for 2020. But John would never see them. After complaining about his living conditions, he was not called back this season to work at EZ Grow.

Zamecnik, who runs EZ Grow with his son Dusty, said John was a disgruntled worker and that's why he wasn't invited back.

"There are reasons people leave, Jill can’t get along with Sally…. You know, I appreciate Clinton’s frustration, I mean, he didn't get hired back, and he didn't get another farm."

Under the federal program, workers must have a guaranteed job waiting for them before they are allowed into Canada.

WATCH | A worker reacts to living in a garage:

John remains convinced he was punished for complaining about his living conditions.

"You cannot speak. If you see something that you don't like, you cannot talk about it. You keep it to yourself because any time you talk about it, for sure the next year they will not request you."

VI.

The Zamecniks no longer use the garage for housing workers and built new accommodations for this season. They say they spent approximately $600,000 for six school portables that were inspected and approved last winter.

As part of the SAWP visa process, the federal government requires a yearly inspection of workers' accommodations. The inspections are completed by the local public health authority and guided by provincial standards last updated in 2010.

These guidelines only require a minimal amount of living space per worker — the size of a small eight-by-ten foot bedroom — and beds can be as close together as 1.5 feet. Only one toilet and shower are needed for every 10 residents.

Chopp doesn’t believe it's the farmers' fault if the conditions aren't what Canadians might expect. "They're providing what needs to be there in order to meet that standard."

Last year, Chopp's local health unit conducted 600 bunkhouse inspections and found only seven per cent were non-compliant with existing guidelines.

She believes the federal government should impose an updated and uniform housing standard for all farmers.

John, the worker who complained about living in the Zamecniks' garage, agrees standards need to change because right now they allow for unacceptable living conditions. The garage had passed inspection.

"I'm talking for all the farm workers who are afraid to talk, who don't want to talk and who are allowed to go up there and get victimized and live on a pallet and piece of cloth and all kind of thing,” John told The Fifth Estate on a Skype interview from near his home in Port of Spain.

"If they don’t want to come out and talk for their rights, I will talk for them because it's unfair for a man to leave his family for six or eight months and then come to live in this kind of condition."

VII.

Fears of an outbreak on farms have pushed farmers to take matters into their own hands to protect their workforce. But there are no guarantees of success.

"I have a lot of anxiety around us getting COVID on the farm because we're not immune to it," Brett Schuyler said.

WATCH | Take a virtual tour of migrant worker housing:

He took out bank loans to build five more bunkhouses — at a cost of roughly $15,000 per bed — because he knew it would be safer for workers to have more space to distance. Nine people live in each house.

"In the long-term, more housing is a good thing. There's long-term benefits," he said. COVID-19 simply sped up the business decision.

His largest bunkhouse was once the home he grew up in. In a normal year, it would house 40 people. But this season, he cut that by half. He urged all of his 250 workers to stay within their assigned groups of roughly 20 people.

Only bottom bunks are being used to ensure two-metre distancing, and signs are placed throughout the bunkhouse, reminding people to stay physically distanced.

Despite his best efforts, and with all the precautions, Schuyler's farm was hit by an outbreak this month. On Nov. 3, one worker tested positive for COVID-19. That number grew to 13. Nobody was hospitalized, but 100 of his 200 workers living on the farm were forced to quarantine for two weeks in local motel rooms.

This quarantine cost Schuyler $200,000, he said, and he hopes to recoup at least some of it from government. The Ragoo family was among those who were quarantined.

VIII.

The first known COVID-19 outbreak among migrant farm workers in Canada was at Bylands Nurseries in Kelowna, B.C., in late March.

Less than two months later, the virus would reach a farm in Norfolk County.

Scotlynn Farms — just a few kilometres from Schuyler’s orchards — had one of the biggest outbreaks in Ontario, with more than 200 workers testing positive for the virus.

Tragedy struck in that outbreak. Juan Lopez Chaparro died in a London, Ont., hospital in June after getting sick with COVID-19. The 55-year-old father of four was the third migrant farm worker to die after contracting COVID-19 in Canada. All three were from Mexico and working in Ontario.

According to a report by the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change, by mid-May, 180 calls had come into its hotline from farm workers across Canada. Their main complaint was a lack of health and safety measures, including physical distancing in bunkhouses and on the job.

The report notes workers "insisted that they were unable to change the situation because of their employer's control over their housing, their ability to stay in Canada or their ability to return in the future."

The housing conditions have come under more scrutiny this year, and are being blamed for outbreaks and death.

"A lot of the housing conditions in some of these operations are really poor because the farmers, the employers, don't necessarily want to invest in good labour conditions," said McCrae, who has studied issues surrounding Canada’s food supply system for decades.

"That's why there's so many people packed into small spaces. That's why the conditions for virus spread are so acute."

According to Public Health Ontario, there were outbreaks at 30 of the province’s farms between April and Oct. 16, when seasonal workers started to go home.

Based on media reports, the major outbreaks were at farms with migrant workers living in bunkhouses. In all, 1,364 workers tested positive in that period. The Fifth Estate estimates this represents as much as five per cent of the farm worker population. That’s 10 times more than the proportion of positive tests in the overall population of Ontario by October, which was 0.5 per cent.

Workers' health and safety has become a hot button political issue in Canada. In June, the NDP's Brian Masse accused Employment Minister Carla Qualtrough of failing to protect migrant workers this season.

"When the minister signed them coming into this country under the conditions of COVID-19, she signed their death warrant," he said.

"We know that the system is broken, and we are working hard to fix it," Qualtrough replied during question period in the House of Commons. Her department has launched a review of the program.

But when The Fifth Estate contacted the minister to ask what additional steps would be taken to fix the program, Qualtrough declined an interview request.

After multiple outbreaks on farms in Ontario, B.C. and Quebec, with nearly 2,000 workers contracting the virus across the country and three dying, federal Health Minister Patty Hajdu called this season "a national disgrace."

Brett Schuyler recognizes that the farm worker program has attracted some negative attention this year. He even favours improvements to the program and insists our food supply would be in dire trouble without seasonal agricultural workers. "I am concerned about [that negative attention] putting the program in danger."

Schuyler said the outbreak on his farm is over and the workers are all healthy.

But the pandemic continues to wreak havoc on the lives of the workers from Trinidad, including Frederick and the Ragoos. There is a backlog of Trinidadian nationals trying to get home from around the world. They require an exemption from their government to cross the closed border and proof of a negative test for COVID-19 within 72 hours of travel.

"It looks like there’s going to be a hundred people spending Christmas here," Schuyler said, adding that the farm is "doing everything we can to help make it as good of an experience as you can, but I’d rather be in Trinidad in the winter than here, and I know it’s a lot of sacrifice for a lot of people."

The stranded workers' jobs are ending and some may not have suitable housing for deep cold, although Schuyler’s housing is adapted to winter living.

The federal government says it is working with its counterpart in Trinidad and Tobago and with local authorities to make sure workers "have access to adequate housing and income support programs to which they are entitled until their return home can be arranged."

That can’t come soon enough for Frederick, who said he feels "very depressed, frustrated, angry" about not knowing when he can get back to his family.

IX.

Chopp doesn't see improvements to the program coming fast enough to avoid a repeat of the problems next year. She said the federal government can’t come out in February, for example, and expect farmers to change their bunkhouses especially when workers can start arriving in March.

"The clock is ticking for next season already. They need to understand that these housing constraints can't be addressed just like that for 600 bunkhouses."

Brett Schuyler wants to be part of the decision-making for housing standards, as well as the return of workers next season.

"We want to be the gold standard" of farm worker programs around the world, said Schuyler.

"It could be a great gateway for — and it has been — for things like immigration and making Canada a better country because anybody who's been on this farm for a couple of years is somebody that would be a blessing to have living here because they're just good people."

He also said that when it comes to the program, Canadians should consider that when they're not supporting Canadian agriculture, they’re supporting it somewhere else.

According to MacRae, the Canadian agriculture system needs an overhaul, but the failure of our system is not knowing how to manage progressive change to avoid crises.

"I always like that people want to talk about the food system, but it really worries me that the only time we really talk about it is when there's a crisis…. And then when the crises hit of course we're all scrambling."