March 11, 2021

New Brunswick heard about its first presumptive case of COVID-19 a year ago today.

Since then, 29 men and women in the province have died from the disease, 20 just this year.

Here is a glimpse into the lives of eight of them — Joanne Beaulieu, Louis Landry, Colette Boutot, Jack O’Dell, Marguerite Godin, Brenda Curwin, Betty Gregoire and Joan Davis — based on conversations with the people who loved them most.

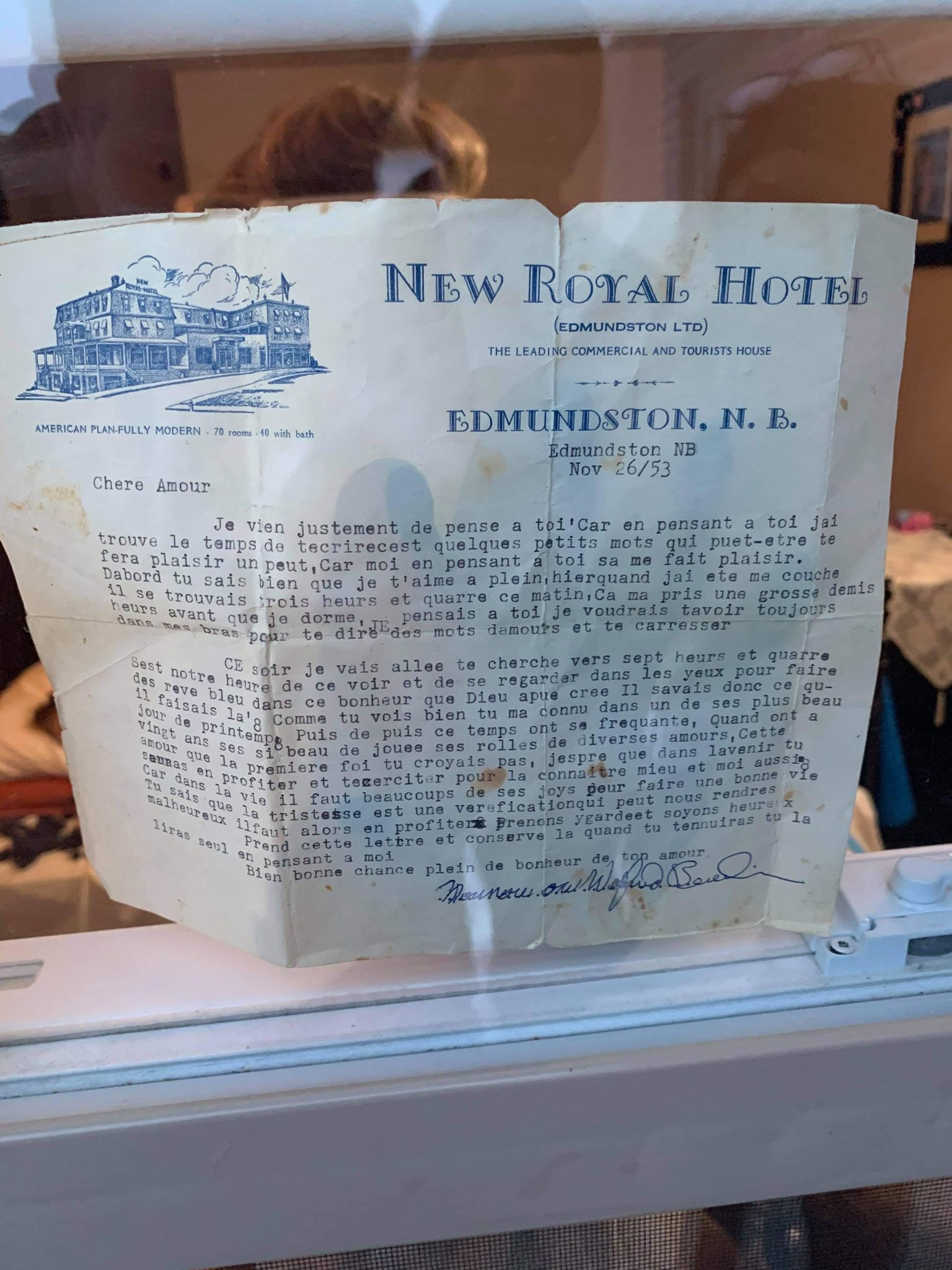

Joanne Beaulieu: A secret love letter

For close to 70 years, Joanne Beaulieu kept a secret love letter written a year before she got married.

On the February day she died of COVID-19, her children learned about the letter, tucked away in her bedroom at the Manoir Belle Vue in Edmundston.

The letter, stained and creased, was typed in French on stationery from Edmundston’s now-gone New Royal Hotel.

It was from Wilfrid Beaulieu, Joanne’s husband.

“It almost gives me the goosebumps,” said their daughter Louise Beaulieu.

In the letter, Wilfrid tells Joanne he knows he loves her because he’s been having trouble sleeping and has been awake at 3:15 a.m. thinking of her.

“I always want to have you in my arms and to tell you words of love and to caress you,” he said.

Wilfrid imagines their future together.

“Take this letter and keep it and when you’re bored, you will read it alone and think of me,” he wrote.

The letter was written on Nov. 26, 1953. And Joanne did hold on to it.

“To keep something like that for 68 years, it must’ve meant something close to her heart,” Louise said from her home in Pierrefonds, Que.

‘She had a hard life’

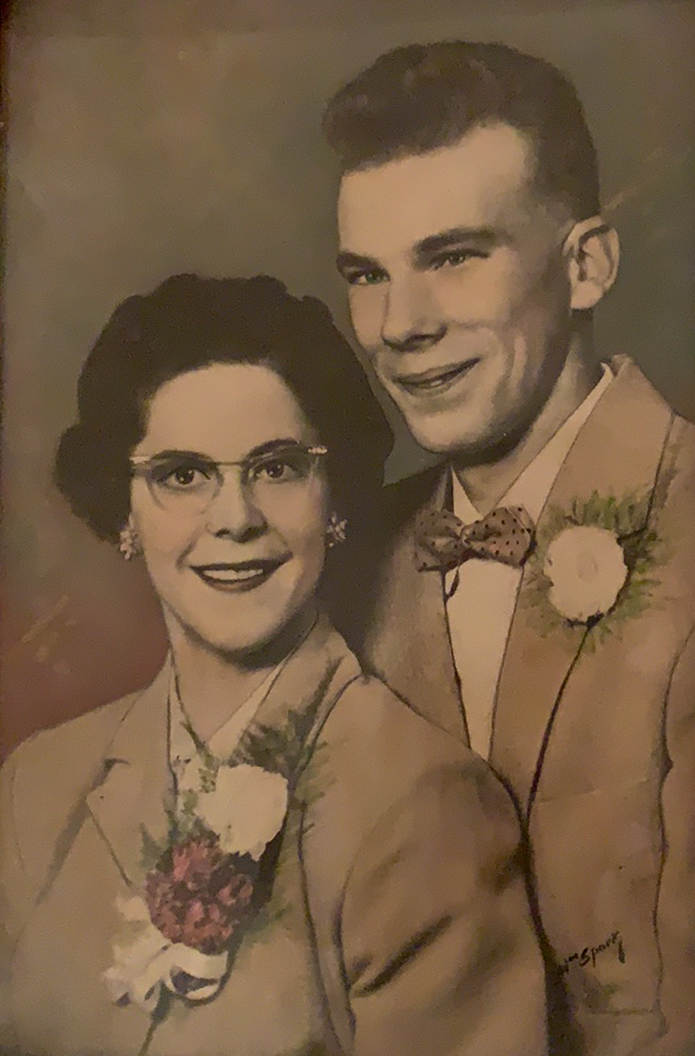

Joanne grew up on a farm in Saint-Basile, northeast of Edmundston, where Wilfrid lived.

She was the second of 16 kids and quit school in Grade 8 to help support the family. She made $1 a day washing laundry at the local hospital.

She married Wilfrid on Oct. 23, 1954, and they had seven children.

At six, her son Charles died from leukemia, and her son Marcel died in 2015 in a bicycle accident.

Joanne never shed a tear in front of her other children.

“I don’t know how she survived,” Louise said. “She had a hard life.”

Always dressed to impress

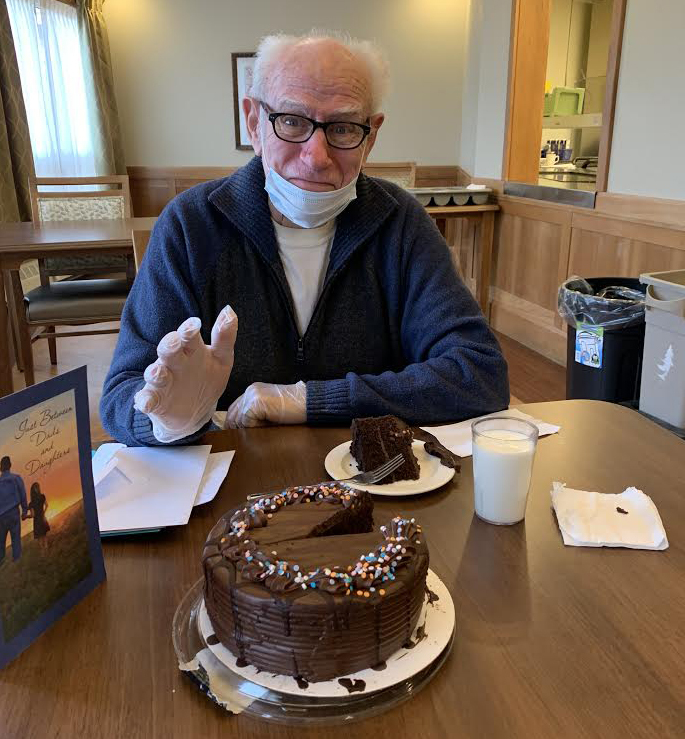

Wilfrid died of a heart attack, and eventually Joanne decided to pack up her belongings, sell the family home and move to Manoir Belle Vue. She lived there almost two years, going for strolls around the parking lot and attending Friday mass at the Manoir.

Joanne liked to dress smartly in a dress or blazer she’d found at a garage sale or thrift store with the perfect shoes to match.

She also kept up with her sewing on her beloved Singer sewing machine.

Residents often joked Joanne was a hairdresser because she hung a large pair of wooden scissors on a hook outside her bedroom door.

But she always corrected them. She was a seamstress. She sewed and hemmed clothes for fellow residents at the manoir.

“She was so happy there,” Louise said.

Joanne, 89, died from COVID-19 on Feb. 15, with two of her daughters and their families standing outside her bedroom window.

At her bedside were angel ornaments she’d collected over the years, and a family portrait. Rosary beads were draped over her head.

“I told my father and my two brothers up there … ‘Come and get Mom,’” Louise said.

Louis Landry: Inventor

For months, the Landry kids struggled to find a spot at the kitchen table of their Saint-Hilaire home, which was taken up by a massive device their father, Louis, called a control panel.

“We had to sit all around the control panel, finding a little spot with our plates because the panel was taking up the entire table,” said Johanne Lise Landry, the youngest of five.

It was part of Louis Landry’s latest invention — a tool that would weigh chickens and send them to different parts of the production chain, depending on their weight.

The family kitchen seemed the perfect place for Louis to work on it.

“That was his shop,” said his eldest daughter, Francine Landry, the Liberal MLA for Madawaska Les Lacs-Edmundston.

Eventually, the panel became a piece of decor in her childhood bedroom. And Louis moved on to his next project.

Among other things, Louis was an inventor.

In the early 1970s, he created the first emergency calling system in New Brunswick.

“He was really something else,” Johanne Lise said.

He founded the Louis Landry’s Musical Band, with Louis on organ, Francine singing and playing percussion, Johanne Lise, who sang and played clarinet, and their brother Ghislain, on drums.

For close to a decade, they would pack their station wagon and travel across northwestern New Brunswick to play at weddings, anniversaries and dances.

When Ghislain’s leg was in a cast after a motorcycle crash, Louis devised a contraption that allowed him to press his big toe against a button that would sound the bass drum.

The two sisters were convinced their father could do anything.

He was a primary school teacher and principal and taught electronics at the community college. He was also a mentor to students at his electric motor repair business, including people with disabilities.

In the mid-1960s, Louis also served as mayor of Saint-Hilaire, his hometown, south of Edmundston.

The Madawaska Regional Correctional Centre was built under his mandate. But one of his greatest successes was a project that never came to be.

Louis adamantly opposed construction of a large water tower because “it would damage the scenery” of the tiny village.

So he travelled to Fredericton to negotiate an inground water system.

He won.

Making dad proud

Eventually, Francine also went into politics, winning a seat in the New Brunswick Legislature in 2014. She was minister of economic development and the minister responsible for Opportunities New Brunswick in Brian Gallant’s cabinet.

Her dad laughed about her political status, and whenever his eldest daughter walked into a room, he would say, “Oh, there’s the politician and the minister coming.”

“That was his way of telling me he was proud.”

At that time, Francine helped launch a tuition program for New Brunswickers who couldn’t afford a post-secondary education.

Her dad told her that if that was the only thing she accomplished in politics, then her job was a success.

“He was so proud of that program.”

A love of learning

Louis was curious, always looking to learn something new by reading or prowling the internet. He studied Italian, fish, Shakespeare and family genealogy going back six generations.

He printed graphs from his personal weather station to compare weather year to year, and grow trees and flowers from seeds he collected and kept in a basement fridge.

As a kid, Johanne Lise would go with her dad to pick up seeds along the Trans-Canada Highway.

They also shared a passion for astronomy.

And when the International Space Station was passing over the house in the mid-’90s, he was sure he could see the Canadarm.

“He was screaming in his slippers, ‘Look at that! We see the Canadian arm,” Johanne Lise said, laughing. “I said, ‘No Dad, it’s not the Canadian arm. It’s too far away.’”

A broken promise

Johanne Lise made a pact with her father.

When it was his time to die, she would play You Raise Me Up by Josh Groban, one of their favourite songs.

Louis, 89, died from COVID-19 at the Villa des Jardins nursing home in Edmundston on Feb. 11.

Johanne Lise wasn’t able to say goodbye or play his song.

But in Louis fashion, his grandson Christian Landry came up with an idea. Outside the nursing home, Christian set up a purple spotlight toward the night sky.

That way, Louis could find his way home.

“You’re there with the stars that you loved so much,” Johanne Lise said.

Colette Boutot: 'A wonder about the world'

At 17, Colette Boutot would vigorously scrub her sister’s living-room window to get a clear view of the handsome man driving by on his old farm tractor.

“That window had never been that clean,” said Monique Boutot, Colette’s daughter.

Colette and Normand met in the northern New Brunswick village of Lac Baker. Colette was there caring for her older sister Laurette, who had just had a baby. Lac Baker was about eight kilometres from Lac Jerry, the Quebec village where Colette grew up.

Her dad often joked that in winter, the dirt road between Lac Baker and Lac Gerry had no snow.

Snow wasn't going to stop a young man in love, Monique said.

“He was shovelling his way to her place."

The couple lived together at the Manoir Belle Vue in Edmundston for almost four years and celebrated their 66th wedding anniversary in December.

Then they both contracted COVID-19.

Normand, 89, recovered. But Colette, 84, died on Feb. 14, lying next to her husband, holding hands.

As Normand cried for his wife, nurses wiped away his tears.

“It was heartbreaking to see this poor old man suffering like that,” Monique said. “Seeing his wife dying and there was nothing nobody could do.”

A mother at 18

Monique, the eldest of five children, was born 10 months after her parents were married. There was only an 18-year difference between Monique and her mom.

“My childhood, I remember my mom doing things we wanted to do.”

The family mostly stayed close to home in Lac Baker. They’d sled on the mountain behind their house, snowshoe in a giant backyard of farmland, skate and ride horses.

“She was a play buddy.”

Colette would often pick up caterpillars, ants or four-leaf clovers and make up stories about them.

“She would make me feel a wonder about the world,” Monique said. “I saw the world as really big and full of stories of love and things to love.”

Life on the farm

While Normand was away working as a lumberjack in Quebec and Maine, Colette would wake up at 5 a.m. to milk and feed their cows. She often joked about getting slapped in the head by a cow’s tail.

“She never met a living being that she did not love ... maybe except spiders. She did not like spiders very much.”

Normand wasn’t much of a handyman, so Colette — all of five feet tall — taught herself how to build things. She worked on home renovations, put up wallpaper and built their bed from old wooden planks.

Colette also read about history and geography in encyclopedias scattered around the house.

She dreamed of travelling the world.

A light gone

Colette’s zest for life carried on into her 80s.

Just three years ago, she was snowshoeing behind the family house in Lac Baker.

“Even in her old age she could run circles around me.”

In the afternoons, Monique often brought Colette to her house for visits, and they’d sneak in a glass of cold white wine, Colette’s favourite.

“She liked to pretend she was someone else with her glass of wine and that she was a big madame,” she said. “It was like playing with dolls.”

Monique said she’s carried a huge weight since her mother’s death.

It’s Colette’s sense of wonder and sparkling blue eyes that she will miss most.

“It’s a light that is gone from the world.”

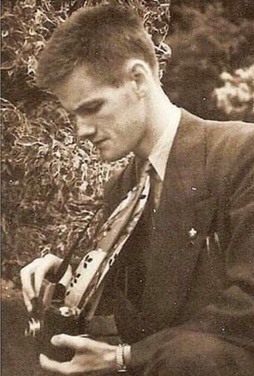

Jack O’Dell: One final note

Whether Jack O’Dell was driving the Fundy Trail or marvelling at New Brunswick’s covered bridges, he always had a camera with him.

“He would even sit there on the couch and take a picture of the TV if there was something nice on the TV,” said Susan O’Dell-Ring, Jack’s daughter.

Jack owned about 10 cameras and many lenses, but his two Nikons were his favourites.

The 79-year-old died Jan. 12, and his daughter is still coming across pictures he kept when he lived at her home in Dieppe.

Thousands of them were stored away in boxes and on disks, and there are books of slides.

“I open up a cabinet and there’s 10 more photo albums,” said O'Dell-Ring.

Jack took pictures of flowers, relatives at various family events, scenery and tourist attractions like Peggy’s Cove in Nova Scotia.

A love of photography

When Jack moved to Shannex in Saint John about a year ago, he brought his camera with him.

He had developed dementia and often lost his camera.

“So he’d go to Costco to buy a new camera,” O’Dell-Ring said. “I took a couple of those back.”

A few times, Jack was convinced someone had stolen his camera, but it would later be under a blanket in his room or in the backseat of his 2020 bright blue Honda Accord parked outside.

“Every worker at the Shannex has at least once looked for Jack’s camera.”

'He enjoyed life'

When he wasn’t taking pictures, Jack would be fiddling with his ham radio, so he could talk to different people from his earlier life.

“He really liked tinkering and building stuff,” O’Dell-Ring said.

He was a cabinet refinisher for Prestige Homes MMA. At one point, Jack landed a job at Home Depot in Moncton, so he could spend more time with people talking about tools.

He built his family a home in Sussex and a cottage on Prince Edward Island.

Throughout his life, Jack had jobs that took him on adventures.

After high school, he served in the Royal Canadian Navy. He also worked for a transport company, and lived in Toronto and Montreal with his family.

“He enjoyed life,” O’Dell-Ring said.

‘The king and queen of Lily Court’

At the Shannex, he lived in the room beside his wife, Dianne, in Lily Court.

The couple met in high school. They could look out their bedroom windows and see each other’s houses in Moncton’s old west end.

They were known as the king and queen of Lily Court, had their own table in the dining area, sang and played Bingo together. Jack would often colour with Dianne.

“If Dad was walking around. … Mom would be sitting down and she’d go, ‘Jack, you sit over here, you’re my husband.’”

O’Dell-Ring was hoping to throw her parents a 53rd wedding anniversary on Aug. 30, but the pandemic stopped that plan.

Famous for passing notes

Jack, who required a tracheostomy because of esophageal cancer five years ago, couldn’t speak. But this didn’t stop him from socializing.

He would often communicate with family and nursing staff by mouthing words.

He was also famous for writing notes, usually printed in black pen on old napkins or the bottom of Kleenex boxes.

“Anything he could get his hands on, he would just write,” O’Dell-Ring said.

She went to visit her parents outside their bedroom windows on Jan. 12. Her father had COVID-19, and O’Dell-Ring knew as soon as the nurse opened the blinds to his room that he was dying.

While the nurses held his hands and rubbed his head to say their goodbyes, she noticed a note written in blue left on his nightstand.

“Please take care of my Dianne.”

Marguerite Godin: Goodbye to ‘Mama’

Marguerite Godin, a custodian for 14 years at Simonds High School in Saint John, would play tricks on co-workers by hiding cleaning supplies, so they’d have to go look for a mop or broom down the hall.

“She would do anything for a laugh,” said Joanne Savoie, Golden’s second oldest daughter.

Godin had three daughters and a son, who she often joked was her favourite child because he was a boy and the youngest.

“She never wanted to hurt anyone’s feelings even though she had no filter.”

‘The life of a party’

Godin moved from Tracadie in the northeast of the province to Saint John with her husband, Norman, who grew up in Bathurst.

They met in Montreal at an Acadian gathering. Three months later they were married.

“He would do whatever Mama asked,” Savoie said.

The couple would pick blueberries in the summer, go deer or moose hunting in the fall.

The whole family would go on camping trips across New Brunswick, a tradition passed down to their grandchildren.

They’d also take their children on fishing trips around Garnett Settlement outside Saint John.

While Norman fished for brook trout, Marguerite would lay a blanket somewhere in the grass for a picnic of fruits, sandwiches or fried chicken.

“She was just the life of a party, wherever she went."

She cooked her famous meat pies for her children as a reminder of their Acadian roots.

“Dad would cut all the meat and Mama would make them in the kitchen.”

Extended family would always visit unannounced, but Godin would always make sure to have food on the table.

“You could never go into my mother’s house, and not eat,” Savoie said. “Anybody was welcome.”

A home away from home

Three years ago, Godin moved into the Shannex nursing home in Saint John because she had developed dementia.

She was known to staff as “Mama” or “Frenchie” because of her thick French accent. Marguerite thought many of the nurses and other Shannex residents were her children too.

“She was so family-oriented, that was her big thing,” Savoie said. “She just loved her family.”

She was quite the flirt too. She often told the male staff they were her boyfriends or they were going to get married.

“She’d always go around and slap everybody on the butt.”

Savoie learned her mom had COVID-19 on Jan. 6 and was certain she would beat it.

“The feistiness is definitely one of the things that she never ever lost.”

‘Just go with dad’

The next day, Marguerite developed a cough. Her health went downhill from there.

Four days before her death on Jan. 19, family members gathered outside her palliative care window.

They said goodbye using an iPhone. Nursing staff held up an iPad for Marguerite, who stared at the ceiling.

“She was just so strong-willed, the little monkey,” Savoie said.

“We kept saying, ‘Mama, please. Just go with Dad.’”

Staff comforted Marguerite with chocolate and eggs sprinkled with brown sugar, her favourite.

'Mama’s the strongest lady I have ever met in my life.'

They read her passages from the Bible and played a mass on TV.

They even played Kaw-liga, a song her late husband sang to her when their kids were growing up.

“My mom was in palliative care, unresponsive and a tear [came] down her eye.”

Savoie is still in disbelief over her mother’s death and the disease that took her.

“Mama’s the strongest lady I have ever met in my life.”

Brenda Curwin: Family is forever

When Robbie Curwin visited his hometown of Moncton, his sister always made sure his favourite dessert was on the table.

“Whenever I came home, there was a tray of poutine à trou waiting for me,” Robbie said.

“She would make me about 12.”

Brenda Curwin adopted the tradition from their mother, Betty, who would make the Acadian apple pastry whenever Robbie was about to head back to university.

After their mother died, Brenda made sure she learned to bake it.

“It was important to her that I still had that love pouring in, and for that I cherish her,” said Robbie, who lives in Toronto.

Homemade gifts at Christmas

Robbie said his sister didn’t have a lot of money or material things, but she would do anything for family. The eldest of five made sure her siblings and extended family had handcrafted gifts to open at Christmas.

Robbie remembers the pot holders and kitchen towels his sister knit and sent to his home in Toronto.

“Those pot holders now hold a special meaning to me.”

Over the years, Robbie and Brenda talked over FaceTime about childhood memories and trips to their family cottage at Anne’s Acres near Bayfield on the Northumberland Strait.

Typically, they would arrive at the cottage on a Friday. Then all five Curwin kids would head to the beach with their dad, who would hoist each onto his shoulders and dive into the water.

Robbie said his sister was particularly fond of those trips to the beach.

“She [was] a daddy’s girl.”

At the cottage, Brenda was surrounded by aunts, uncles, cousins and siblings.

They had bonfires, climbed trees, went fishing and took part in annual lobster boils.

“She’d be able to destroy those lobsters,” he said. “She wasn’t shy about cracking those open.”

At the cottage, Brenda and her siblings shared bunk beds inside a small room at night

“It was cramped quarters but there was a lot of love.”

A passion for genealogy

Those family trips to Anne’s Acres led to Brenda’s passion for genealogy

Her online research has connected Curwins from across New Brunswick and helped distant relatives discover their family roots.

She found out the Curwins were descendants of Alexander Graham Bell, who invented the telephone.

“That was her baby,” he said. “She just loved to do that.”

Brenda lived at Manoir Notre-Dame in Moncton for the past two years because of poor health. Robbie worried about his sister when the pandemic first hit.

“I was like, ‘Oh my god,’ if it gets bad in New Brunswick, she’s a sitting duck.”

‘I love you Brenda’

Brenda died from COVID-19 on Oct. 17 at the age of 64.

Robbie spoke to his sister three hours before she died. Her breathing was heavy, but she tried to convince her younger brother she was fine.

“I felt really compelled at the end of our conversation to say, ‘I love you Brenda.’ And make sure she heard that,” he said. “I said it loud and very strongly. And with conviction.”

She said “I love you too.”

After spending years apart, Brenda will bring her family together once again this summer, when the Curwins gather at Anne’s Acres to celebrate her life and her love for family.

“It’s like that saying, you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone,” Robbie said.

Betty Gregoire: Learning without school

Betty Gregoire was in her early sixties when she boarded a plane for the first time.

Her nephew, Brian Gregoire, had offered to take her to Florida for her first trip south.

“I took her almost everywhere [I] went,” he said. “She was so easy to get along with.”

Betty tried dancing and spent a lot of time at the beach.

Brian remembers eating in the hotel restaurant, where the duo played tricks on their server, pretending they were siblings.

“She was my aunt but we were more like brother and sister,” said Brian, 68.

On weekends she worked part time at his shop, Brian’s Hair Styling in Campbellton, where she shampooed and swept hair off the floor.

“She was very well-loved by the people.”

‘She could do anything’

Betty grew up on a farm in Broadlands, Que., with 13 siblings.

There were no buses, and school was a five-kilometre walk away. Betty had to quit in Grade 5 because she damaged her right leg playing on bed springs with her brothers and sisters inside the old farmhouse.

“She grew up with that all her life, but she made out quite well.”

Staying home, she learned to knit, quilt and cook by observing her mother.

“She was very smart,” Brian said. “She could do anything.”

Betty was known for her Scotch cakes and sampling recipes from the cookbooks that sat on her kitchen shelves.

“If she had three at a table or eight at a table, it didn’t matter,” he said. “She was prepared for anything.”

A final visit

Betty never married, although she’d dreamed of having children of her own. Instead, she had more than 20 nieces and nephews. She taught more than one niece to knit.

She could never say no to a game of Auction Forty Fives and was a stickler about the rules.

“She’d watch us just like a hawk that we wouldn’t cheat.”

The last time Brian saw his aunt was on Valentine’s Day in 2020 — just before the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in New Brunswick.

He had brought her a card, chocolate and homemade mustard pickles because she was allergic to flowers.

Brian would always send his aunt cards at every holiday or special occasion at the Manoir de la Vallée in Atholville.

“She looked forward to her cards.”

Betty died from COVID-19 on June 13. She was 88.

Joan Davis: A mother’s faithfulness

The last time Trevor Jones called his big sister in Saint John, she was coughing heavily and seemed confused.

But Joan Davis, 79, made a point to ask about her youngest son, Troy, who is mentally disabled.

“Troy was always on her mind,” Trevor said. “Every time you talked to her, Troy would enter the conversation somewhere.”

Even when Joan developed dementia three years ago, she tried her best to care for Troy, who’s now in his early 50s. He’d spend half his time at her apartment and the other half at a special care home.

“There’s no way to catalogue ... the bridges she had to cross in order to keep Troy in the home and give him the best life possible.”

Troy was the youngest of six kids. She made sure he graduated high school. And later got a job at a vocational school, making rags for companies and pins for elections.

Joan kept him busy, took him on errands to the grocery store and Dollarama — his favourite excursion.

She also made sure to turn on the TV when Power Rangers or Star Trek came on.

“A lot of people probably don’t understand how difficult it was to raise a child with special needs — and Joan did that.”

Eventually, the dementia took over and caring for her youngest child became too much.

Joan moved into Shannex Lily Court in Saint John about a year ago.

“She was happy there,” Trevor said.

A sister who seemed more like Mom

Trevor and his sister were 17 years apart. Joan was the eldest of five siblings.

As a kid, Trevor remembers travelling from Sussex to Joan’s pink house, which he felt was better suited to a beach in Florida than Mountain Road in Saint John.

At her house, Trevor built snow forts and played hide and seek and hockey in the outdoor rink with his nephews.

“The boys kind of grew up like my younger brothers.”

As he grew older, Joan’s home became a safe haven for Trevor.

Joan immediately took him in during Trevor’s separation from his wife. And it was the first place he visited when he travelled back and forth from the military base in Petawawa, Ont. During those visits, Trevor spent a lot of time catching up on family news over Joan’s home cooking.

“I almost looked at her as a mother.”

The curler who scored an eight-ender

Trevor said he will remember his sister’s energy and her heart for adventure.

She and her second husband, George Davis, also known as Sonny, bought a Yamaha Star Venture motorcycle. They covered many kilometres across Atlantic Canada and along the Eastern seaboard.

“Sonny was the pilot and she was the willing passenger.”

They loved that motorcycle so much they kept it inside their mini-home in the winter.

“Not quite in the living room, but close,” he said.

Joan belonged to Thistle-St. Andrews Curling Club and taught many new players about the game. In the mid-1970s, she and her team scored an eight-ender during the city and district mixed-play tournament.

She was also a skip for her team in the New Brunswick Senior Ladies Championship. It’s a sport her dad used to play and she passed down to her children.

“It sort of ran in the family.”

Trevor said his sister didn’t have the strength to survive COVID-19. Joan died of the respiratory illness on Jan. 21.

Troy learned about his mother’s death from another brother, Peter.

He cried when he found out.

But Troy still plans to get a birthday gift for his mom, who was supposed to turn 80 this week.

“Troy was the most important thing in her life,” Trevor said.