August 3, 2019

Hundreds of thousands of people are expected to take part in Pride festivities across Vancouver this weekend, ranging from Sunday’s parade to dozens of events in bars and other venues.

But some older gay activists remember a time when fighting for LGBT rights was less of a party and more of a struggle.

Don Hann, 73, was one of the key members of the Gay Alliance Towards Equality (GATE), which operated in Vancouver from 1971 to 1980. Hann recently opened his archives to showcase some photos from that era.

GATE battled for the rights of gay people, from the B.C. Human Rights Commission to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Here are some photos that highlight some of the organization’s key moments.

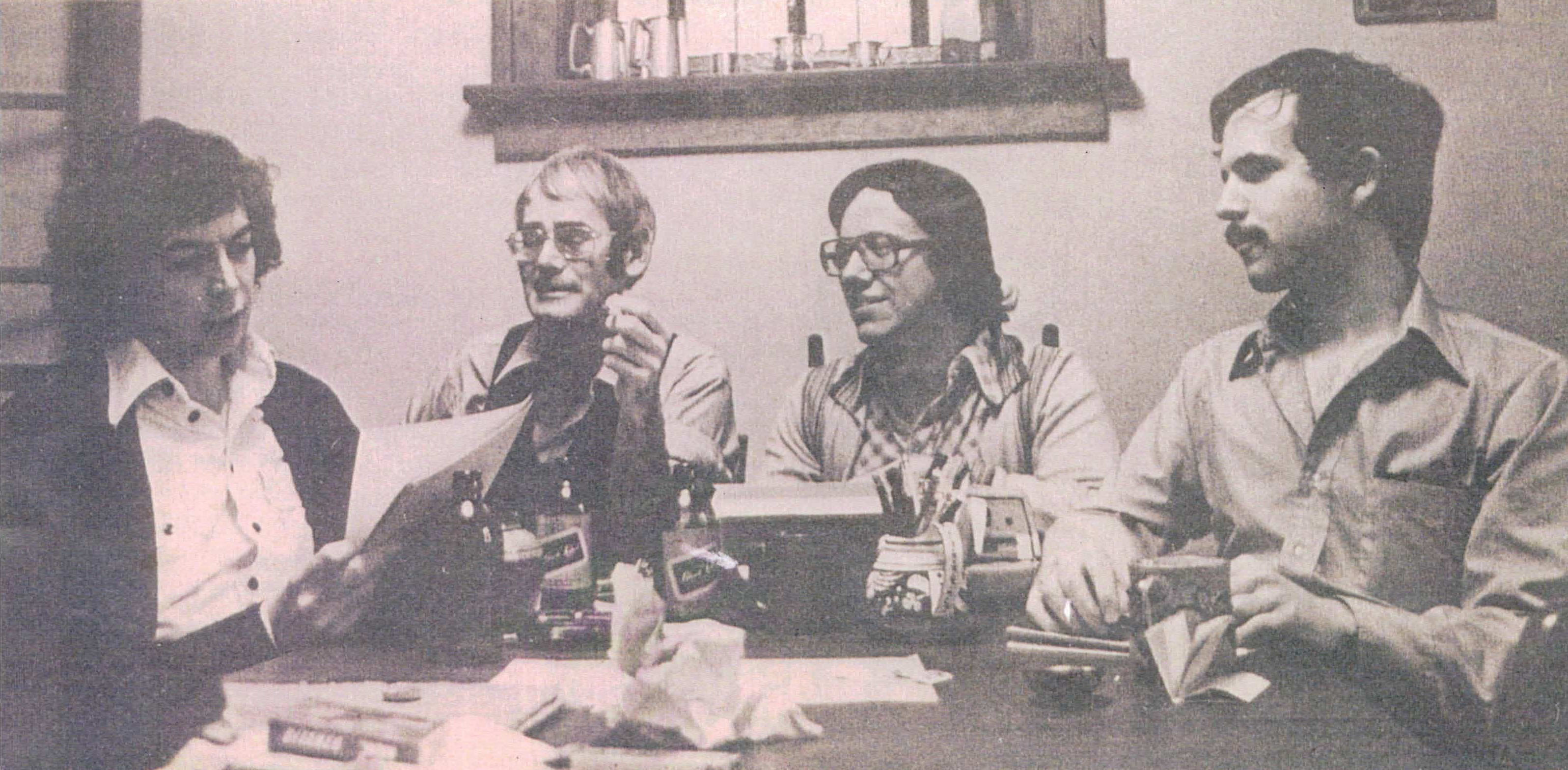

This photograph, taken in 1972, shows one of the early GATE meetings at a house in East Vancouver, near Pender and Nanaimo streets.

The house was the home of GATE chairman Maurice Flood and Cynthia Flood, with whom he had two children and maintained a partnership after becoming a major figure in the gay liberation movement. GATE organizer Bob Cook also lived there.

The house was home to many GATE meetings and was also where the organization would put together issues of Gay Tide, its newspaper, and create picket signs for rallies.

“We'd all get together on a Saturday afternoon at that house quite often,” Hann said.

Maurice Flood and Michael Merrill, pictured in the photo, later died of AIDS.

The house was also where meetings took place to discuss GATE’s strategy in response to the Vancouver Sun refusing to publish a two-line advertisement for Gay Tide.

When the Vancouver Sun refused to publish the ad, GATE’s first legal response was to file a human rights complaint.

Hann says the Vancouver Sun appealed that decision, and the fight eventually made its way to the Supreme Court of Canada.

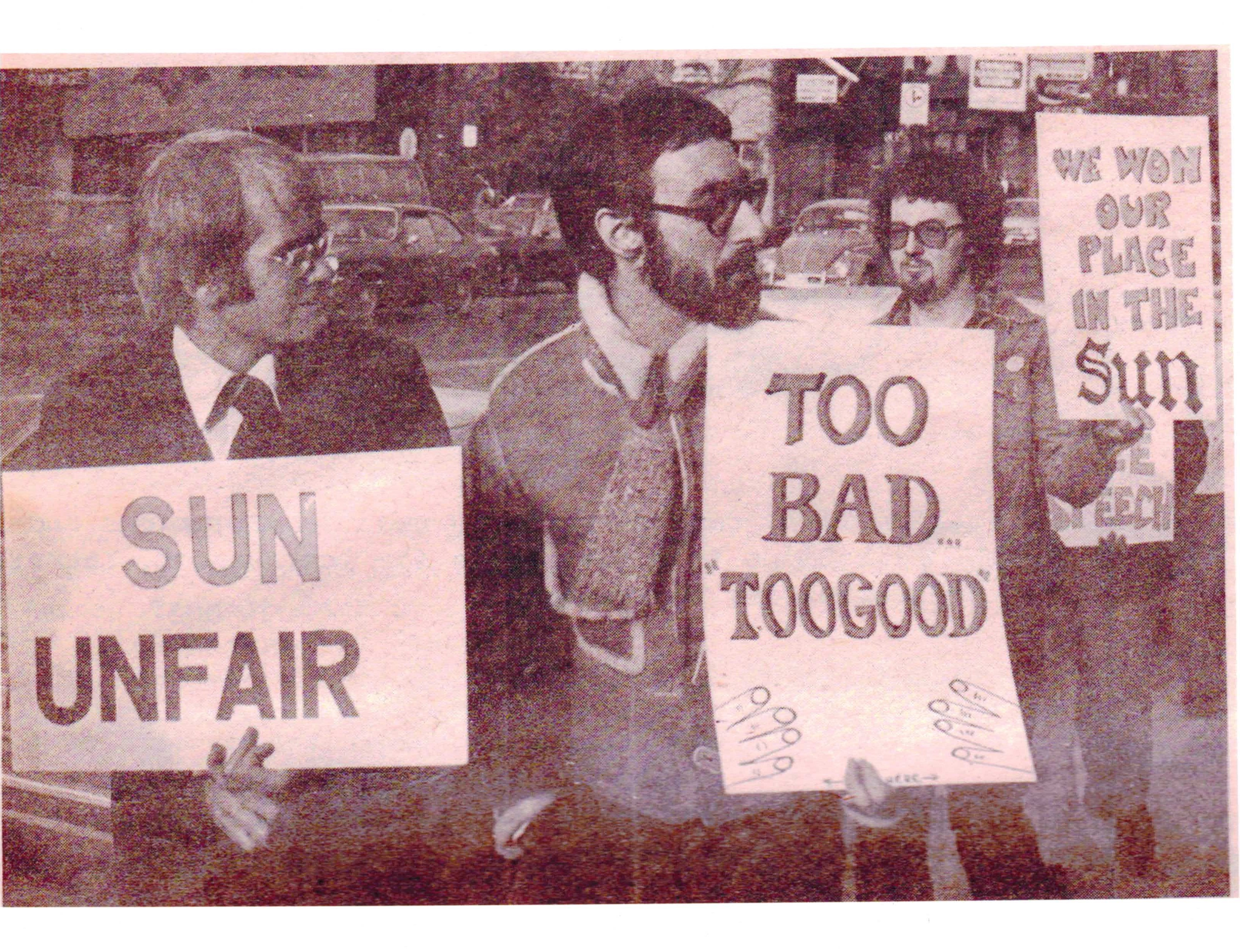

Hann says the photo above shows one of many rallies GATE held to speak out against the Sun’s response to the ad.

“Our attitude was that this was a political battle, it wasn't strictly speaking a legal battle,” Hann said.

Although the rallies were small in size compared to today’s, Hann points out that the vast majority of gay men were still in the closet and couldn’t risk being associated with the LGBT rights movement — especially if media were covering the event.

Some passers-by did support the protesters, Hann says, while others were more hostile.

Hann says support grew over the decade as GATE actively sought support from other groups like the labour movement and church organizations.

One of GATE’s key backings came from women’s liberation groups.

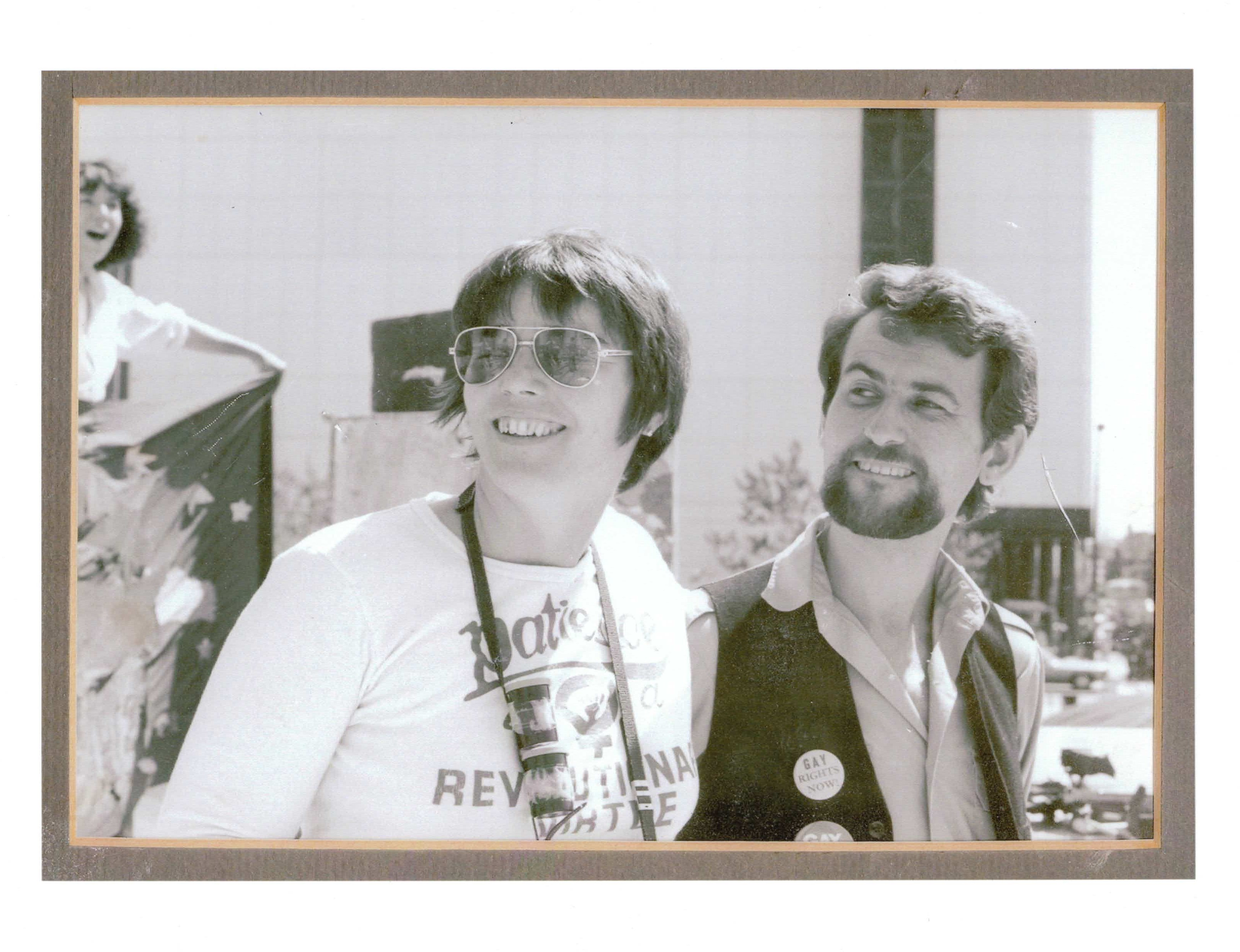

In the photo above, Hann stands with Cy-Thea Sand, a key figure in Canada’s early feminist movement, at a rally in Robson Square to speak out against an anti-gay act of violence at a festival that year.

Hann says the rally was well-attended because of support from about 16 organizations, including Sand’s. Hann and Sand became friends over the years, he says, and it was thanks to support from people like her that GATE was able to advance.

“She had a huge influence on me in many different ways,” Hann said.

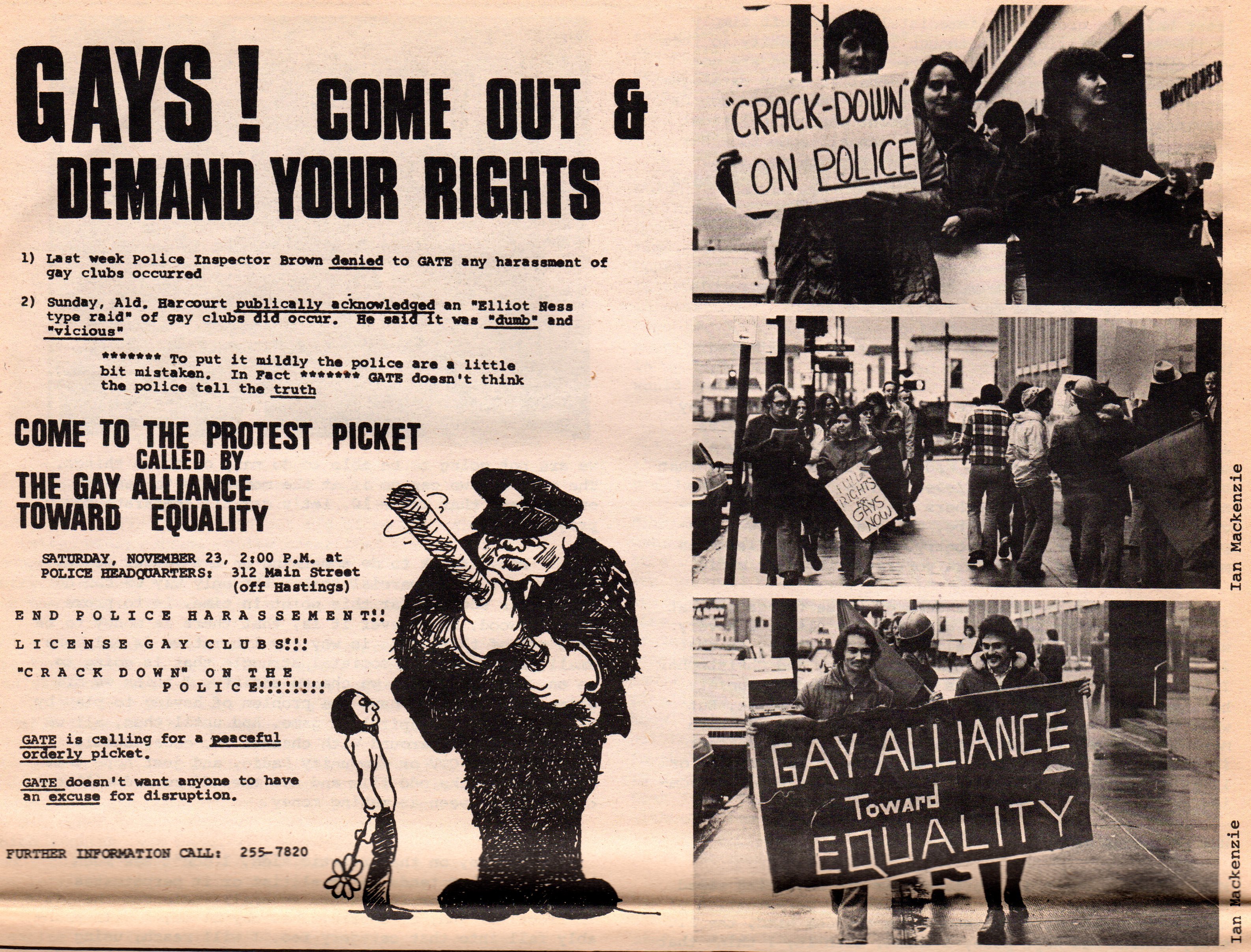

One group Hann says GATE did not have support from was the police.

Officers actively patrolled gay bars and other meeting places and arrested men under various pretences, he said — sometimes releasing the names and addresses of those they caught.

“The police were our enemies in the 1970s,” Hann said. “There was a deliberate attempt to crush the movement and it ruined lives.”

This wasn’t the case only in Vancouver, Hann points out — police departments across North America sought out and targeted gay men and women.

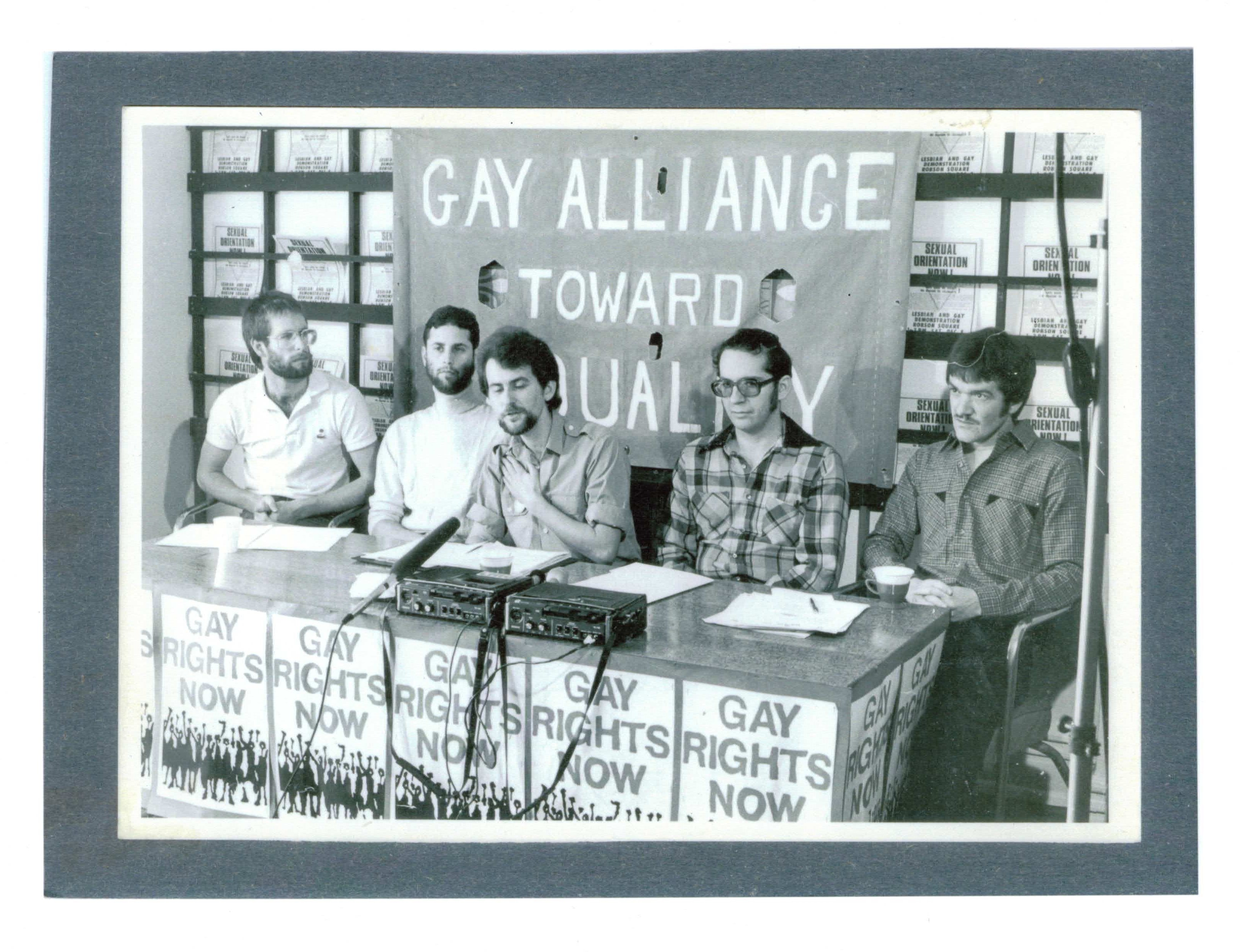

One of GATE’s last events, in 1979, was a conference calling out one of the members of the B.C. Human Rights Commission for being a homophobe.

It wasn’t the first time GATE had spoken out against the commission. Hann says the organization had held other rallies opposing decisions in discrimination cases that involved employers and border crossings.

By 1980, GATE could have gone on but some of the organization’s key members had left and it was losing members. The organization folded.

“History had brought GATE into existence and history seems to have decided that its project is done,” Hann said.

The leaders and members had no idea what was around the corner — the AIDS crisis that brought with it what Hann calls “a massive tsunami of suffering.”

Hann says the work that organizations like GATE had done over the past decade, including all the support it had built, helped pave the way for the gay community’s fight for justice during the AIDS era.