July 1, 2018

Not long after St. John's photographer Paul Daly arrived at the Newfoundland Memorial at Beaumont-Hamel nearly two years ago with his two sons and a few friends, he felt goosebumps on his skin.

"Where are you folks from?" asked a Parks Canada guide soon after they arrived.

"Newfoundland," said one of the boys.

"Welcome home," the guide told them. "The land belongs to you. It is your land."

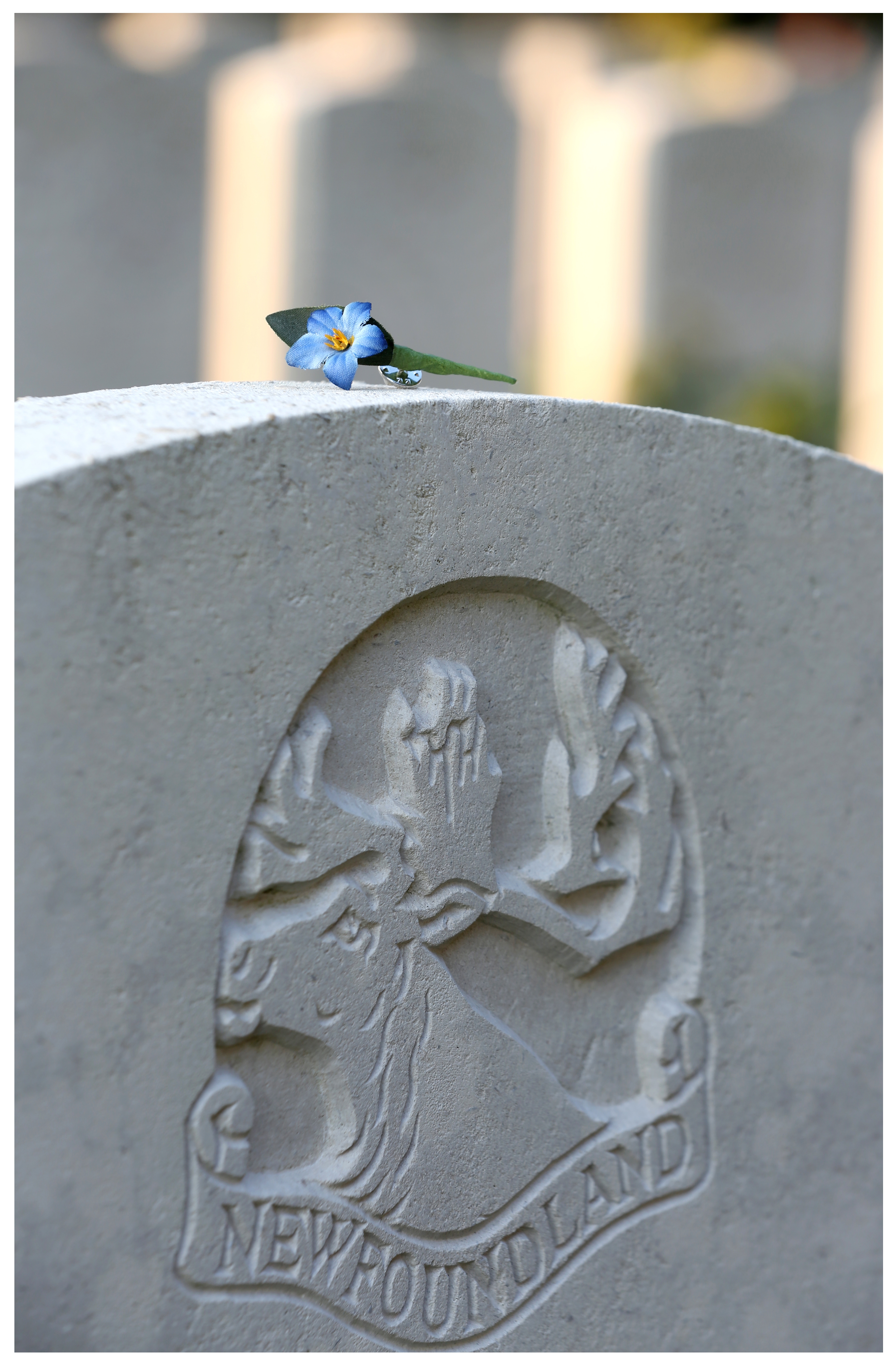

Purchased by the Dominion of Newfoundland in the 1920s, and maintained now by Parks Canada, the Newfoundland Memorial is something of a pilgrimage for many people from Newfoundland and Labrador, who know all too well the effect that Battle of Beaumont-Hamel had.

The numbers of the loss remain startling to this day.

Beaumont-Hamel: What happened, and what went wrong

Infamously, only 68 members of the 801 members of the Newfoundland Regiment who fought at Beaumont-Hamel on July 1, 1916, were able to answer roll call on July 2.

Some 324 soldiers were killed, presumed dead or missing; another 386 were wounded, sometimes grievously.

Different stories from the same time

Daly, who emigrated to Canada from Ireland, also knew about the Battle of the Somme, the catastrophic First World War offensive, but from a different lens.

He grew up hearing about the Dublin Fusiliers, and about his great uncle, Joseph Reilly, who died during the brutal battle.

Describing himself as a "Newfoundlander by choice," Daly came to know about Beaumont-Hamel.

It was almost inescapable.

"What impressed me most is that it is so ingrained in the DNA of Newfoundanders," Daly said in an interview.

After starting their visit at the Memorial's interpretation centre, Daly and his party moved to the trenches.

Bright green colours of a summer's day belied the grim reality of what had taken place a century before.

What shocked Daly the most: the shortness of the distance between the trenches and the placement of the Germain machine gunners.

"They would have seen their faces," he said, adding that it must have felt like a firing squad.

On a summer's day, even with other visitors arriving, Daly was struck by how peaceful and quiet the memorial was.

He noted that Parks Canada staff had posted signs asking for no noise, and could not imagine anyone being loud.

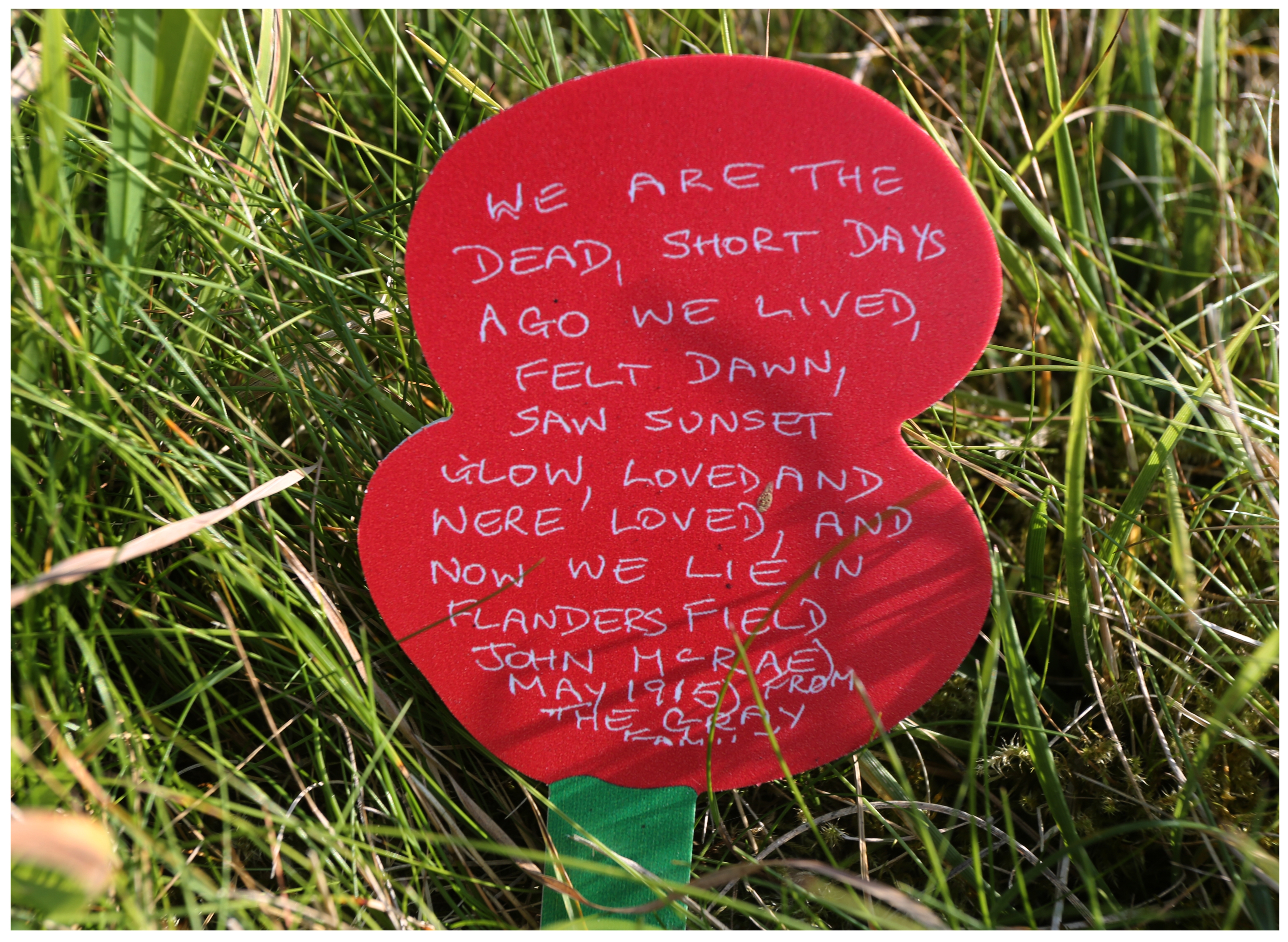

"You feel as though you are on sacred ground," he said.

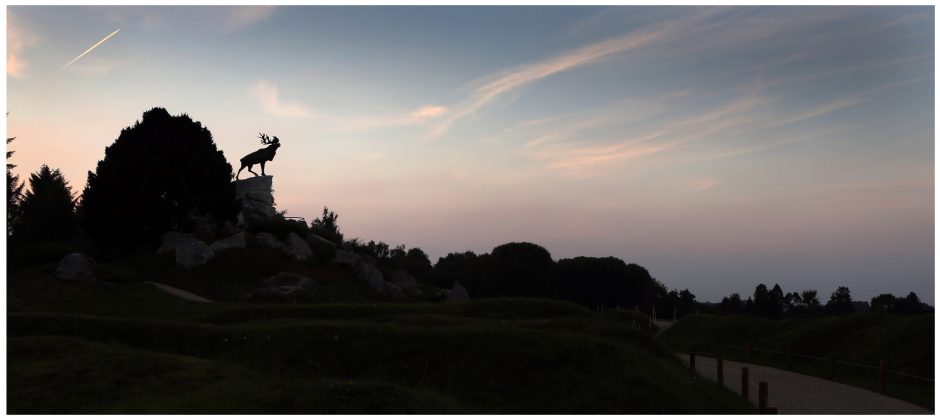

That evening, Daly returned to see the sun set at Beaumont-Hamel, and to see the striking view of the caribou statue against the sky. He found the scene deeply emotional, and resonant of the losses that afflicted so many families, and what was then a small dominion on the eastern side of North America.