November 10, 2018

"You see that 'Gramma, you are loved' thing? That probably belonged to Silas."

"I want to see his bedroom."

"He even has a lead. He probably had a dog."

It’s a sunny Friday in June. Six British schoolchildren are peering in the window of an old, abandoned house in Ochre Pit Cove, in Newfoundland’s Conception Bay, home once to the Edgecombe family.

They've never been to Newfoundland before. But they know a lot about Silas Edgecombe, and how he died.

In fact, they and other students at their school have made it their mission to look after his final resting place, and the graves of other Royal Newfoundland Regiment soldiers — as well as one nurse — who died in England during the First World War.

The cemetery across the street

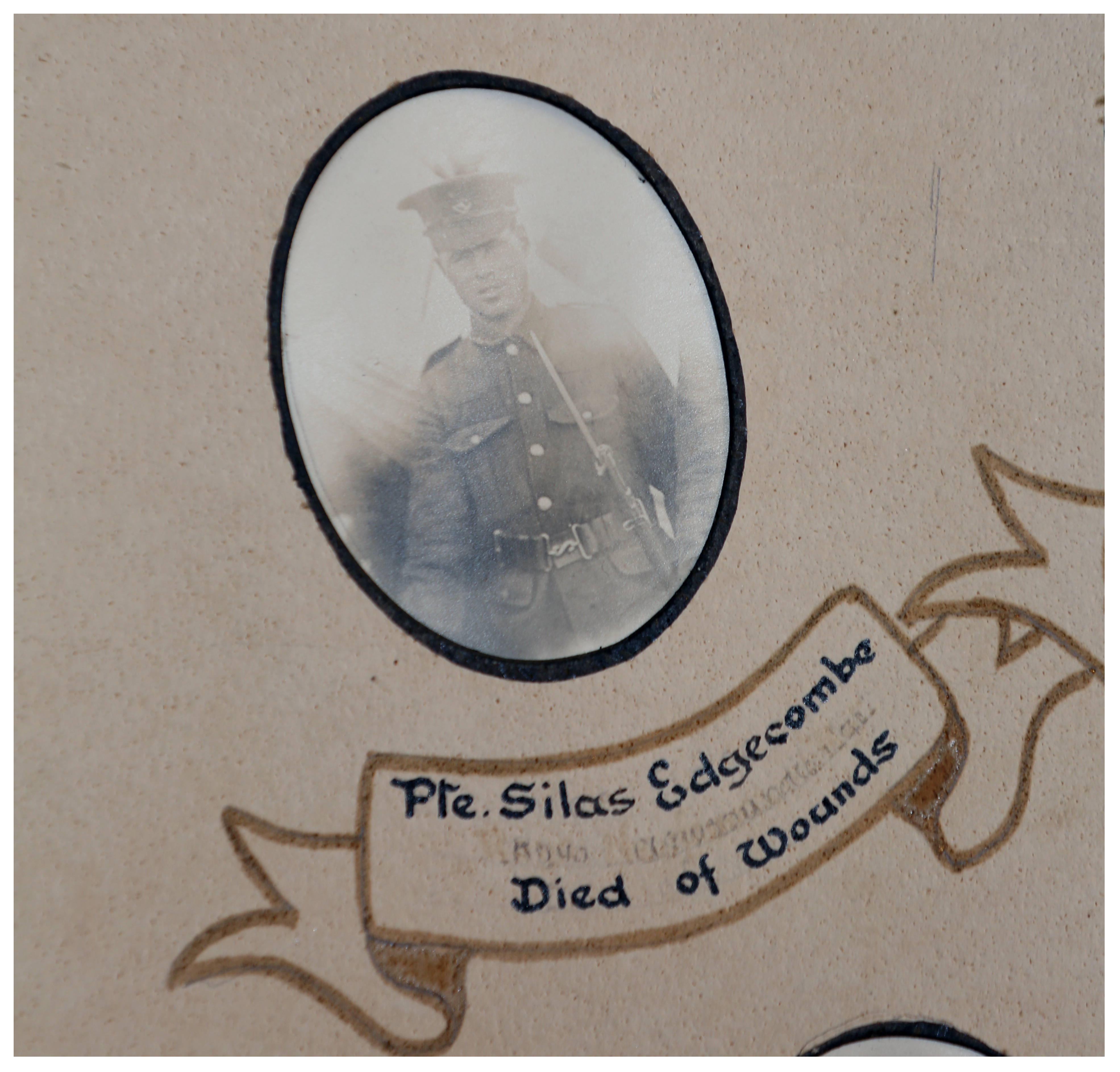

In March 1915, 22-year-old Silas Edgecombe left the cove to enlist in the Newfoundland Regiment to fight in the First World War.

A little over a year later, he was seriously wounded in battle at Beaumont-Hamel, in France. Shipped back across the English Channel for treatment, Pte. Edgecombe died in the 3rd London General Hospital on July 11, 1916.

He was buried nearby, in Wandsworth Cemetery.

On Magdelan Road in London, right across from that cemetery, sits Beatrix Potter School, where for the last 15 years students have made it a mission to care for graves.

This visit to Newfoundland is the culmination of a school project that has touched hearts on both sides of the Atlantic, and which has gone further than anyone had imagined.

"We've come this far and found out where he actually lived. When we found him, he was just a guy in a grave," says Sasha Cellino, 11, looking up at Edgecombe's house in Ochre Pit Cove.

"Now we know much more about him."

The students have lunch with Silas's niece, Jeanette Gillingham. Born after Silas died, she doesn't know much more about her uncle than the British children do, but she appreciates their efforts and their interest.

"It's a wonderful job for them to be doing that, isn't it? Anyone so young as them."

Maureen Doyle Gillingham, a local teacher, and her husband, Roger Gillingham, the principal, have organized a potluck lunch for their visitors, a lunch like one they believe Silas would have had a century ago. The guests dine on fish cakes, meat cakes, and "some fish and brewis — that's a traditional dish that we've had here for years and years and years."

Doyle Gillingham says she was moved to tears when she learned the extent of the school's bond with the 18 Newfoundlanders whom the Royal Newfoundland Regiment buried across the road.

"It's [brought] the story back to Newfoundland, back to the people who should be remembering — us. We didn't really know that this was even happening in Wandsworth and I think because of their story, we will remember even more so now than ever before."

A curious question

The school's connection to Newfoundland and Labrador began — by accident — in 2003. During a school outing, a young student noticed a small group of headstones bare of the bright red poppies that members of the British military had placed on the other war graves in Wandsworth.

Steph Neale, the head teacher at the school, was curious to find out why; that impulse eventually turned into book reports and biographies on the 17 soldiers and one nurse from Newfoundland. Inside Beatrix Potter School, a corridor is decorated and dedicated in their memory.

Students have even created a little play about "their soldiers," which they've performed at other schools in south London.

Most importantly, they visit the Royal Newfoundland Regiment plot twice a year — to mark Newfoundland’s Memorial Day on July 1, and Remembrance Day and Armistice Day on Nov. 11 — to plant a paper poppy on each grave, and to say the names of the Newfoundlanders aloud.

A voyage to Newfoundland

Now the six students, six of their parents and a handful of teachers have come to the province to learn more. Their first stop is St. Bon's, where four of the soldiers buried in Wandsworth went to school in St. John’s. One after one, relatives of those soldiers stand to thank the Brits for what they do.

"It's [brought] the story back to Newfoundland, back to the people who should be remembering — us." — Maureen Doyle Gillingham

Tracy Hennessey told the students about her grandmother, Gertrude Edwards Hennessey, and how her great-uncle John is buried at Wandsworth. Another of her brothers died during the war. "My father recounts stories of her as he was growing up and how on Remembrance Day, and on other days special to her, she would often sit with their photos and cry quietly. You can only imagine how painful it must have been to lose two of your beloved brothers at such a young age."

Audio documentary

Listen to Ted Blades's full radio documentary on the connections between the Beatrix Potter School students and relatives of those whose graves they care for.

Hennessey told the students that in an earlier time, travel to London was practically impossible.

"What was equally painful, I think, is that he was thousands of miles away and no one could get to him back then," she said. "You may think that your gestures are probably not very great, but to my family, your gestures of dignity and respect and love to our beloved John are monumental."

'Like being hit by a train'

Such moments proved to be emotional for the visitors from the U.K.

"It was like being hit by a train,” said Beatrix Potter parent Jo Anderson. "We were just expecting to do an average school visit. When we got there, no tissues, completely ill-prepared. Probably a little bit jet-lagged. I have found it an absolutely once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

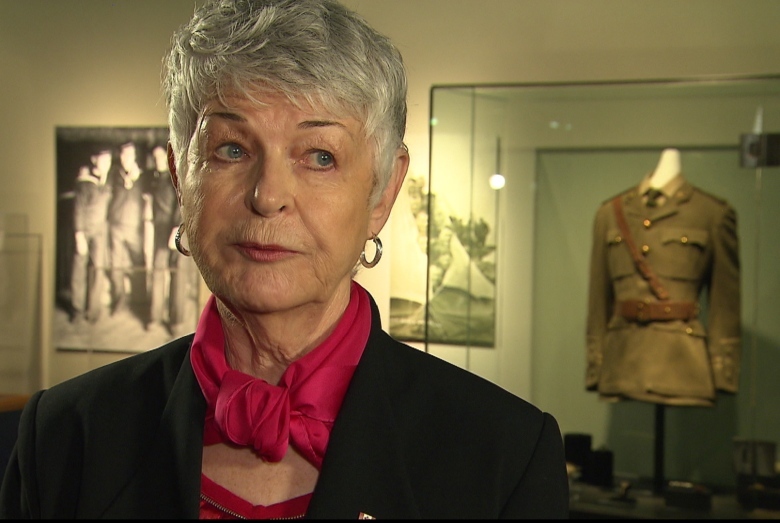

At Newfoundland and Labrador’s provincial museum at The Rooms complex in St. John’s, they meet Elinor Gill Ratcliffe, the philanthropist who helped create the Royal Newfoundland Regiment exhibit. “It's moving beyond belief,” said Ratcliffe, adding that what the students do is “now part of our history.”

“To think that our soldiers are being tended to by a devoted group of young children who are only 11 and 12 years old. And now we get the chance to give back a little and have them learn even more about the regiment and the people in the graves that they go to. I think it's amazing."

There are tears all round at a large gathering of relatives later in the week. Stories are told, photos are shared.

Former CBC Land & Sea host Dave Quinton — a great-grand-nephew of Augustus Quinton, Regimental No. 2195 — has a photo for the children of an old bar of soap.

"I was going through the attic and I found an old envelope. I was about to throw it out in the garbage but when I opened it. It turned out to be a little tiny round bar of soap. The note from my aunt — who died 30 years ago — says this bar of soap was military issue. It was in his packsack when he died.”

The soap had been sent from England a century ago.

"It's quite an honour that we've been allowed to meet the families of the people that we look after,” says Oscar Heard, a Beatrix Potter School student. “It got quite emotional because they were telling their stories of all their relatives.”

Classmate Sophia Anderson added, "I know much more about the soldiers now, what they did and where they lived. We saw Bertha Bartlett's hometown and that was really amazing." Bartlett, a nurse from Brigus, is the only woman buried in the Newfoundland Regiment plot at Wandsworth.

Despite the chill, a moment to warm the heart

On July 1, Newfoundland thanks the British visitors by trying to freeze them to death.

They've been asked to march in the Memorial Day Parade and lay a wreath at the cenotaph so they put on the nicest clothes they've packed, not their warmest. It's July, after all.

But a cold fog creeps in from the Atlantic as the ceremony drags on and soon everyone is shivering. What sustained them, says Sasha Cellino’s mother, Costanza De Toma, was the warmth of the crowd.

"Somebody came up to us and gave us Anzac biscuits that they'd baked for us the night before. We were all freezing to death,” she said. “We were very grateful for those biscuits. People were looking at us, kids were coming up to us — I've never had that before in my life."

"When we were marching away after the service, the crowd were relatively quiet when the regiment went past," said Jo Anderson, Sophia's mother. "And then when we passed, [the crowds] all started clapping and shouting, shouting, ‘Thank you.’ I was like, ‘Oh my goodness.’ I just found it incredibly moving and it's something that I will take to my grave probably.”

For the Beatrix Potter School community, thoughts have turned now to how keep the connections going.

“Every new cohort of children that get into Year 6 continues the project and finds out a bit more about these soldiers but this has been quite a step forward,” said De Toma. “We now would like to have maybe the kids from St. Bon’s come over to meet us. We need to carry this on and find a way of ensuring that this doesn't doesn't die out ever.”

Steph Neale, the head teacher who was curious to find out about the Newfoundland graves, puts his faith in his students.

"I think you underestimate the youth,” he said. “They understand more than than you think about the feelings of people and the feelings of communities. On this trip we've met some of the families. It's very emotional.

“They are now more than just a soldier lying there with a rank and a war record, that they died. We actually know a lot more about them. They're human to us.”

The Newfoundland visit was transformative for the children.

"We didn't think that we were doing a lot when we were in Wandsworth,” said Alice Goldberger, a Year 6 student.

“We just thought we were researching some people. But then to come over here and realize that we were actually doing quite a lot, it opened our eyes.”

Archival special

In 2015, Ted Blades had the opportunity to visit Beatrix Potter School in London, and observe how the school community has embraced the graves of 18 Newfoundlanders. Listen to his documentary below. You can read a feature Ted wrote here, as well as our followup coverage here.

Ted Blades is the host of CBC Radio’s On The Go across Newfoundland and Labrador. Paul Daly is a freelance photographer living in St. John’s.