July 27, 2016

That first phone call confirmed his worst fears. It was like walking to the edge of a cliff, then free-falling.

"Fire is right here! And it’s burning houses in Beacon Hill!"

Hearing that, Jody Butz wanted to scream.

How did this happen? We thought we knew where it was going. We thought it wouldn’t come here.

There was no time to feel the shock. No time to notice the tears that soon came to his eyes.

The fire was here. And it was already beating them.

Butz slammed the phone down and called another firefighting crew, telling them to head to the neighbourhood next to where the flames had burst through.

“Get to Abasand. Tell me what you’re seeing, and phone me directly. Beacon Hill is on fire. We’re getting overrun there. Make sure you have a water supply. Dig in and be safe.”

Be safe. He knew the words were inadequate for what was likely to come.

Be safe. He knew the words were inadequate for what was likely to come. In a few minutes, they would find out just how inadequate.

The fire roared into Abasand, burning up to 300 feet above the trees. The half-dozen firefighters stationed there were like toy soldiers in front of a giant.

Before the fire could roll over their heads, Butz told them to leave.

Or, he must have. Looking back now, the assistant deputy chief of operations at the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo can’t remember actually giving that order.

But he does remember thinking two things.

If he and his team didn’t figure out soon what the hell was going on, this thing would destroy Fort McMurray. And if those men died trying to leave Abasand, they would be the first of many killed on that day.

Jody Butz was one of three men tasked with figuring out how to stop a ferocious wildfire from consuming Fort McMurray in May, 2016.

In the first 24 hours, he, Darby Allen, Dale Bendfeld and the teams they commanded fought hard, and without much outside help.

They grappled not only with how to save the city, but also with whether their agonizing decisions would save lives — or further imperil them. And some of those decisions still haunt them.

May 1

In military battles, the people in charge describe something called "the fog of war."

It’s a state of uncertainty that leaders often face when trying to calculate the strength of their foe’s position — and their own. The only way out of that fog is to move faster and be smarter than your opponent.

But what happens when that opponent has no strategy — just a white-hot breath that destroys and kills?

The wildfire that came to be known as "the Beast" started approximately four kilometres southwest of Fort McMurray on Sunday, May 1, 2016 in a muskeg forest popular with ATV riders.

The blaze was just one in a list of fires. Alberta Agriculture and Forestry simply called it “the Horse River fire.” But it grew quickly.

By midday, it was a big enough threat that the head of the forestry department phoned Darby Allen, fire chief of the Regional Municipality of Wood Buffalo.

Allen was at home eating lunch when the call came. The house was empty and quiet. His grownup sons no longer live at home and his wife was on vacation in their native England. Allen put down his cheese sandwich and picked up the phone.

When you’re fire chief of a municipality in the middle of the boreal forest, smoke and wildfires are typical and usually pretty easy to manage. But what Allen heard on the phone that day grabbed his gut.

"I realized, based on the weather, based on the conditions, that it was going to be coming this way," Allen said.

He immediately drove to the Regional Emergency Operations Centre on the edge of Fort McMurray and phoned some of his closest colleagues.

That included his friend Dale Bendfeld, who is head of Fort McMurray’s municipal law enforcement. Before that, Bendfeld was a police officer and a soldier who served in Afghanistan, Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

When Allen’s name showed up on his cellphone, Bendfeld was standing on the back deck of his house watching a fire burn across the street. It was one of two fires the region was already dealing with during an unseasonably dry and hot spring weekend in northern Alberta. In this weather, the smallest spark could flare into flames quickly.

"We’ve got a bit of a problem," Allen told him. "Would you come in and give me a hand?" His words were casual, but his gravel voice was serious.

Bendfeld joined the chief at the emergency centre. What’s going on and what do we need to be doing? he asked himself. The military man started taking meticulous notes.

By suppertime, they had called in more help. The mayor arrived. And the crowd in the emergency headquarters grew to about 20 people.

All afternoon they had watched the winds feed that Horse River fire as it marched northeast toward the city. And they worried.

One of the people watching was Jody Butz, a lead firefighter for the region. He got the call as the evening sun softened and he and his family pulled into the driveway of their northside neighbourhood.

They were bringing home a brand new fifth-wheel trailer they’d just bought in Edmonton. Admiring neighbours stood around with his wife and two young sons, chatting. A bit of a party.

Butz had seen smoke on the horizon that day, but thought it was 'nothing too concerning.'

No one flinched when Butz traded his flip-flops for his boots and uniform and headed into the office. The life of an emergency worker — never really off duty.

Butz had seen smoke on the horizon that day, but thought it was "nothing too concerning." He felt differently when he heard how large the fire had grown and how quickly the wind was blowing the flames toward town.

Before 6 p.m., the fire had burned about 130 hectares, or roughly the size of 80 soccer fields.

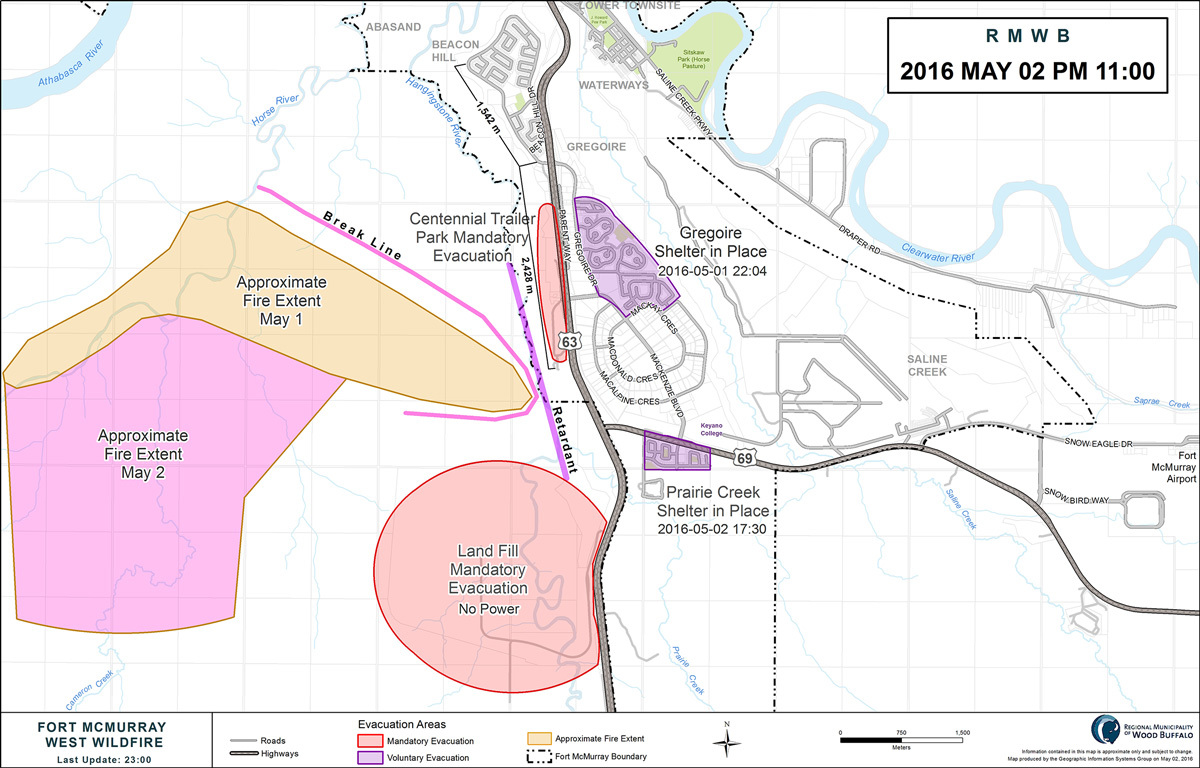

Mayor Melissa Blake announced evacuation notices for about 4,500 people in neighbourhoods officials thought were in the most danger. They issued an evacuation notice for residents in Prairie Creek, Centennial Trailer Park and an area near downtown called Gregoire.

By 10 p.m., the mayor and council had declared a local state of emergency. When that happens, political leaders step aside and let emergency responders take over.

As director of emergency management, Darby Allen essentially became Fort McMurray’s new boss. Dale Bendfeld became his deputy. And Jody Butz was named chief of the town’s firefighting operations.

Allen had been a firefighter for more than 30 years and he led an experienced team. But no amount of training could have prepared them for what was to come.

The way to fight a wildfire in the forest depends on where it is and how fiercely it’s burning. Firefighters can attack it from the air by dropping buckets of water and flame retardant. They can also battle the flames with special equipment on the ground, often using helicopters to drop firefighters into isolated areas that don’t have roads nearby.

Allen’s team of municipal workers wanted to do whatever they could to stop it. But right then, the fire was burning outside of Fort McMurray — so it was under the jurisdiction of Alberta’s provincial firefighting crews with the forestry department.

Forestry was in charge of the Horse River fire. But they only had a few specialized wildland firefighters available in Fort McMurray. And Butz felt it was too risky to take municipal firefighters into the area without more help.

"It’s impossible and it’s dangerous," Butz said of their strategy that first day. "You just don’t get in front of that. You’re going to hurt, if not kill, firefighters."

Forestry sent four helicopters and air tankers to douse the Horse River fire that afternoon, while Butz sent ground crews to a different fire on the north side of town — one that was already getting close to houses.

Soon, it started to get dark. The air crews over the Horse River fire would soon have to suspend their fight.

"That I think was for me, personally, the a-ha moment," Bendfeld said. "Because we now had a fire that’s moving toward us — and nothing between the fire and Highway 63 or the city."

The emergency operations team tried even harder to get people out of the places under evacuation orders — Prairie Creek and Centennial Trailer Park.

"It was a realization moment that it was time for action," Bendfeld said. "Something had to be done, now."

Bendfeld kept moving. He booked a private helicopter for the morning so municipal officials could look at the fire from the air. He helped devise a backup plan as the Horse River fire burned closer to a major power line west of the city.

When it threatened the landfill, Bendfeld and his team called transit drivers and managers in to move all the garbage trucks out. They also called in communications officials and coordinated with RCMP.

Bendfeld stayed up all night. There was too much to do.

May 2

6 a.m.

Monday morning dawned bright and cloudless. It was going to be another scorcher, with a forecasted high of 27C — almost double the average for that time of year.

Jody Butz went up in the helicopter as soon as the sun hit the sky. And before provincial air crews could push him out of it. Alberta forestry workers close off air space above bushfires they’re fighting — an area as wide as a five-kilometre radius around the fire’s edge and 10,000 feet up. They need the air clear for their planes, tankers and water bombers.

But it was important that Butz flew that day. Without his own firefighters on the ground, the only way he could get a sense of how much the fire had grown was from the air.

What he saw that morning was not as bad as he had imagined in the dark. Yes, the fire had marched further toward the south end of town and now burned dangerously close — about one and a half kilometres from the town’s western boundary.

But the leading edge of that fire was narrow. Manageable, he thought. There was little smoke at that time of day, too. Forest fires typically quiet down overnight and into the early morning, when the temperature cools down and the air gets more humid.

The tension started to leave Butz’s shoulders. To him, it was starting to look like the day could turn out all right.

Forestry planned to bring in dozers to knock down trees around the fire’s edge — what’s known as a fire break, designed to stop the flames from spreading. And the wind was blowing southwest, away from Fort McMurray.

"We felt pretty good about ourselves," Butz said. He was still on alert, but he thought "we’ve got a little bit of a head start here. There’s no surprises."

That optimism caught on when he spoke with the emergency team as they got the day started in their windowless headquarters.

Bendfeld didn’t know it then, but he wouldn’t sleep for several days.

By 8 a.m., Bendfeld briefed the mayor and recommended that some residents evacuated from their homes the day before should be allowed to return.

"I wouldn’t say we felt confident it was safe," Bendfeld said. "But it wasn’t as bad as we thought it was going to be."

Bendfeld was so positive that morning that he went back to his regular job downtown in the municipal government building.

He hadn’t been to bed since answering Allen’s phone call the day before. Bendfeld didn’t know it then, but he wouldn’t sleep for several days.

As the day wore on, provincial forestry manager Bernie Schmitte and his team continued their air attacks on the Horse River fire, giving the emergency team regular updates.

Butz needed their advice. His team, like all municipal firefighters, had basic wildfire training, but their specialty was putting out fires in cities, not forests.

"We’re structural. We don’t chase fires through trees, normally," Butz said. "Although we can and we will … and we sure did."

On a typical day in Fort McMurray, there are just 36 municipal firefighters on shift, spread across four fire halls. A small number.

Butz didn’t want to take any chances. By then, his crews were almost finished putting out the fire on the north side that had burned close to homes. But there was still much to do. He asked several off-shift firefighters to get ready to come in. It was also time to think about what to tell the people who live in Fort McMurray. The group scheduled a news conference for Monday evening.

Darby Allen asked his team for advice on what to say publicly about the fire threat. Worry amongst residents had grown that afternoon as they watched the smoke build above them.

Forest fires typically flare up around noon and peak at about 3 p.m., when the temperature is hottest. This fire was no exception. By the end of the day, white ash had started falling like snow in Gregoire. Smoke blocked the sun, creating a strange orange glow.

"Chief Allen asked me from an operations perspective, ‘Give me your feeling.’ And I told him we were pretty comfortable," Butz said. "There wasn’t a lot of uncertainty there. The wind was blowing away from town. We’re two days into this and the edge of the fire closest to town was getting cold."

Butz’s gut feeling matched what Schmitte had been telling the chief that day. But Allen couldn’t shake a deep sense of dread.

"Jody’s like, ‘It’s fine, it’s not that big a deal. These guys [the forestry department] have got a handle on it.’ I was not that convinced about that. But I don’t say anything to Jody. Because it’s not like we’re going home. We’re still dealing with this thing 24/7."

He knew the danger of underestimating a wildfire while it 'slept' at night.

At a news conference at 5:30 p.m., Mayor Blake and the rest of Allen’s team told people living in the Centennial Trailer Park, the neighbourhood closest to the fire, to stay away. But she also announced downgrades to some of the mandatory evacuation orders from Sunday night. Residents who lived in Gregoire and Prairie Creek could now go back home under a new voluntary "shelter in place" order.

Talking about it now, Allen said he doesn’t remember that step, which was announced in a news release published by his official communications team at 10 p.m. that night.

"I don’t remember bringing anybody home and telling anybody it was OK to come home," he said. "I don’t remember anybody agreeing to that." In an interview with CBC that night, Allen certainly sounded wary. Because of heavy smoke, he said then, the forestry department couldn’t find the fire’s edge before the sun went down. So they didn’t really know how big it was, or how close it was to town.

Municipal firefighters hadn’t battled the blaze on the ground that day. But as many as 28 people had helped with the air attacks (seven helicopters and two air tankers) and driving dozers to build the fire break.

The dozers kept working through the night long after the air crews came down.

Butz felt good enough about the situation to go home to sleep. As he crawled into bed beside his wife at around 11 p.m., he remembers telling her, "The fire went away."

Allen wasn’t convinced of that. And neither was Bendfeld, his right hand man.

In his former career as a soldier, Bendfeld led a military crew during the 2003 firestorm that destroyed more than 200 homes in Kelowna, B.C. He knew the danger of underestimating a wildfire while it "slept" at night, and the unease of wondering what it was doing in the dark.

"We call it the witching hour," Bendfeld said.

For the man in charge, a similar unsettled feeling haunted him all night.

"Monday then, maybe things had calmed down," Allen said. "But in my mind, it hadn’t calmed down. Because I knew it was going to go this way. Whether the wind was going to help it or not, it was going to go this way."

May 3

6:30 a.m.

Another clear dawn seemed to banish the uncertainty of the previous night.

Only two news crews from outside Fort McMurray had arrived to cover the fires at that point. And the morning was so clear that one of them considered going home.

"I get up Tuesday morning, and it’s a beautiful day," Allen said. "There’s low plumes of smoke. And people are calling me and saying, ‘It’s great, the fire’s gone away.' "

If he felt reassured, that feeling lasted only as long as it took to drive to the emergency centre.

"When I get in, I talk to Bernie Schmitte, and he says, 'We’re quite concerned about the wind direction today. Because the wind is blowing north/northeast.'"

Right toward town.

On the north side, Jody Butz skipped his morning toast. He wanted to be one of the first to arrive at the emergency centre. Unlike the day before, he didn’t get to go up in the helicopter to scout from the air. So he was eager to hear what his colleagues had to say.

The members of his team who did fly at first light found the view murky and disconcerting. The low temperature overnight had sucked the smoke clouds down near the ground, hiding the fire’s edge. There was still no way to tell how much the blaze had grown.

Bendfeld’s logbook says that helicopter went up at 6:15 a.m. It took a couple of hours after that for the smoke to lift. Forestry would have taken over the airspace by then. So the municipal emergency centre would have to rely on their information.

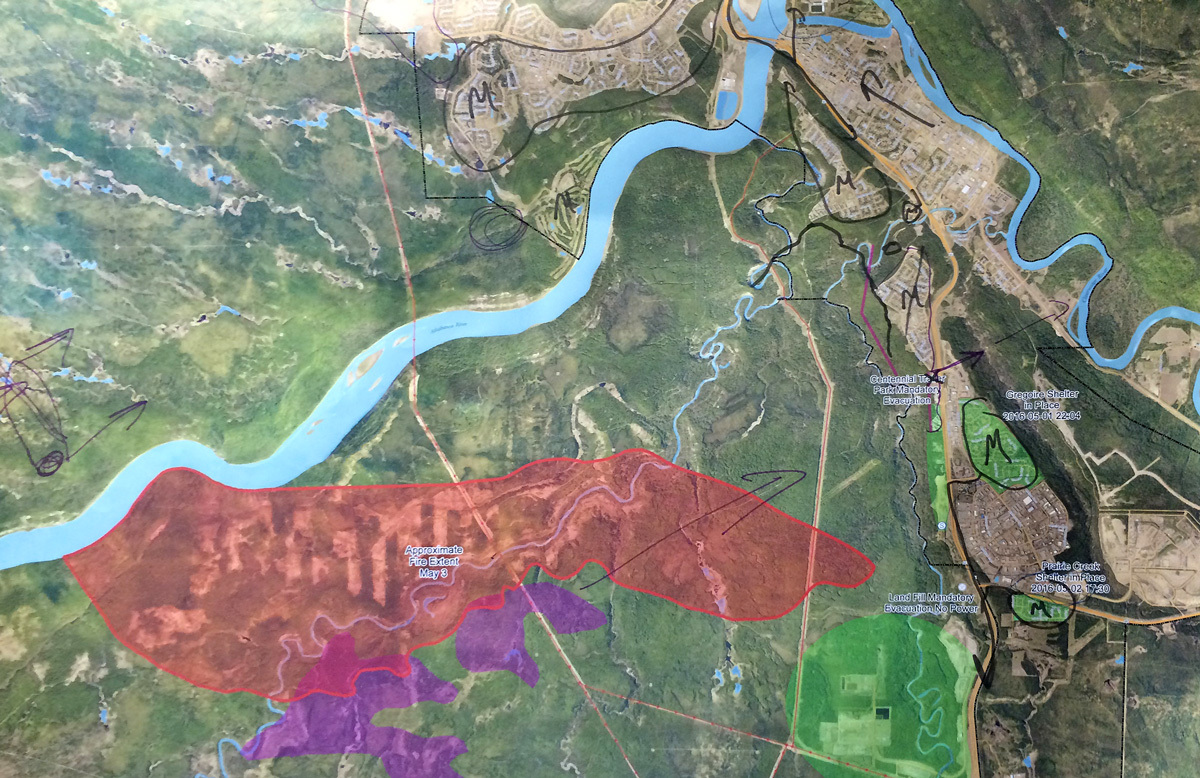

The list of facts the forestry group delivered around 9 a.m. sounded bad. The fire had doubled in size. A press release a couple hours later would say it had jumped from roughly 1,285 hectares the night before to 2,600 hectares — about 1,612 soccer fields. It was now burning within just 1,100 metres of the town’s edge.

Crews had built a fire break around the northeastern tip. But there was little guarantee it would hold the blaze back. That was because this was going to be another hot, dry day. And by noon, they expected the flames would grow so hot and fast that they would move into the treetops — a "crown fire." The kind that spreads most wildly.

Forestry had requested more help. In an interview with CBC that morning, Schmitte explained 60 wildland firefighters were in the area at that time, but it had only been safe to have 30 on the fire the day before. He said 90 more wildland firefighters were on the way. But it would take time for them to get there. It was hard to know when exactly they would arrive.

Schmitte insisted there was no need for residents to leave. In another CBC interview just before 9 a.m., he said he expected the fire to grow, but that it wouldn’t reach the town that day.

"There is fuel for the fire — bush — but it's a distance away," Schmitte was quoted in the story published that morning.

Looking back now, Allen remembers the wildfire expert telling him, "We’ll be fine, we’ll be fine." Yet the chief’s stomach kept churning.

"The speed the fire travelled, the direction the fire is travelling — we know that it’s going to try to jump the river," Allen said.

Rivers are a natural fire break. And the Athabasca, which flows from the Columbia Icefield in Jasper National Park, is four times as wide as the average man-made fire break.

Over the past couple days, experts on his team had told Allen there was no way the fire would jump across the river. That was his comfort.

Even if it keeps burning toward town, the fire will stop at the river.

Then, at 10:30 a.m. Allen got a report that fire had been spotted on the other side of the Athabasca River. A massive jump. More than a kilometre.

Air attack teams tried to put out that runaway ribbon of fire with more water and flame retardant.

"They’re bombing it, they’re bombing it. Bernie’s like, 'We’ll hold it, it’s going to be fine,'" Allen said. “And then it’s 10 hectares away, it’s five hectares.”

It kept coming.

11 a.m.

Allen’s emergency team had planned another news conference for mid-morning. Yet even with the dire details in front of them, no one wanted to announce more evacuation orders in Fort McMurray.

At the 11 a.m. news conference, the mood was jarring. Mayor Melissa Blake gave a statement laced with smiles. Provincial wildfire boss Bernie Schmitte was red-faced and wiped sweat from his forehead as he talked to the crowd.

Darby Allen somehow managed to look both deadly grave and completely casual. "I remember knowing before I did that press conference that we were not going to have a good day."

After hearing the fire had doubled in size and jumped the river, the news crews who had started to arrive in Fort McMurray expected Allen to announce expanded evacuation plans. He did not. Instead, the fire chief warned people to "start thinking about what you need to do."

When pressed, Allen added, "Start thinking that if you had to leave sometime in the next couple of days, what would you bring with you?"

Looking back, the chief realizes what he said then might have seemed vague. But, even knowing what he knows now, he says he wouldn’t go back and change the messaging.

"I remember thinking that I didn’t want to say anything as far as how I thought it might go," he said. "It’s not that you’re trying to keep secrets. But when you’re in front of those cameras, it’s instant. And if I had said, 'We’re in a pile of trouble and we have to get out now,' that’s not appropriate. First of all, it scares people and it panics people. And we hadn’t issued any type of evacuation order.

"So I thought it was appropriate just to mention to people that they should think about it."

About 90 minutes later, the fire roared into town.

Around the time Allen was speaking before the cameras, Butz decided to take some new firefighting recruits on a tour of the emergency operations centre.

They were in their fifth week of boot camp, and had started wildland fire training a couple days earlier. Butz wanted to show them how a centre like this works during a local state of emergency.

At lunchtime, he had to order them out.

He was starting to see worrying reports — not from the forestry experts he relied on for updates, but from social media. People on Twitter and Facebook said they could see flames from the Shell gas station in Beacon Hill.

Right in town.

Butz turned to his provincial colleagues, who looked dumbfounded. "They couldn’t tell me how far away the fire was."

Butz frantically sent a scout to Beacon Hill, the heavily wooded residential area on the west side of Highway 63, and only a couple of minutes from downtown.

We need eyes on the ground, dammit.

The scout told him what he feared most. Fire was already lighting up houses there. And no one had been told to evacuate that neighbourhood yet.

Butz sent another crew of firefighters, who tore up the road to Beacon Hill, sirens screaming. He found out later that some of the new recruits he had just spoken to had ended up on that team.

The sky got more and more black. Butz needed to think ahead. If the fire was in Beacon Hill, he knew it was headed fast to neighbouring Abasand. He sent another crew there. About half a dozen firefighters — all he could spare.

We can’t lose. We can’t be losing already.

The crew dug in to fight. But they were too few and the fire was too big. They would die if they tried to stop it.

So they left. It was all they could do.

"I remember Jody coming to me and saying, 'We’re losing Abasand,' " Allen said. "He was almost crying. And I said, 'It’s OK. Let’s just get on with the rest of it.'"

It was the equivalent of a good, head-shaking slap. Butz regrouped. He knew he needed to change his strategy. He told the firefighters still stationed in Beacon Hill to bypass Abasand and go straight to Thickwood, a northside neighbourhood across the Athabasca River.

"We cannot chase these fires through town," Butz remembers thinking. "We have to get in front of it. Defend our city."

The first firefighters to answer his call scrambled up to a lookout on a trail system on the north side of the river. They peered across the water, the golf club and downtown. What they saw was worse than Butz or anyone on his team had imagined.

This was not the skinny arrow of fire he had seen from the air the day before. This was a sea of flames. Across the horizon.

"There was a fire front as wide as they could see," Butz said. "And it was coming toward the city."

An area where more than 90,000 people live. And only 152 municipal firefighters to defend it.

Bendfeld was trying to take a nap when the fire started burning those first neighbourhoods in Fort McMurray.

It had been two days since he had been to bed, and he’d gone home around midday for a quick rest. Minutes after lying down, he was up again.

"I got a call from Darby telling me he needed me at the emergency centre as soon as possible," Bendfeld said, adding that Allen’s words at the time are "not printable."

Driving Highway 63 across town past Abasand and Beacon Hill, Bendfeld saw fire everywhere.

Everything’s changed. Holy shit.

When Bendfeld walked into the centre, someone said, "Thank God you’re here, Dale."

The room was tense. Voices were raised. It felt disorganized, chaotic. Both of Bendfeld’s cellphones rang constantly.

There were hundreds of questions to ask, decisions to make. The afternoon was a blur, but Bendfeld’s military mind was focused.

'I positioned the city like a battlefield.'

"In combat, I use the term 'information is everything.' If I know what’s going on, I may be able to influence the battle," he said.

"I positioned the city like a battlefield. I started sectioning parts of the city off just as I would overseas. What did we have? What was the threat? What could I put towards it?"

As Bendfeld sectioned off the town map, he narrowed the scope to three priorities: preservation of life (citizens and first responders), vital ground (the highway and the bridge) and critical infrastructure (the water treatment plant).

Meanwhile, Butz was working on his own map. By then he had put out an "all call," asking his 152 Fort McMurray firefighters to come in. The call went out to industrial firefighters from the oilsands, too.

Butz quickly divided these new crews into north and south divisions, separated by the Highway 63 bridge over the river. Individual battalion chiefs would now be in charge of three different sectors: lower townsite (downtown) in the south; Thickwood, the residential neighbourhood on the north side of the Athabasca River; and Timberlea, the next closest residential neighbourhood.

Divide and conquer, he hoped. The Beast can’t trick us again.

The desperate need to get ahead of this thing grew every second, with each new post to social media.

The fire’s in my backyard.

It’s burning my house down.

Flames are crossing Highway 63.

There are embers on the road.

What was true? What wasn’t? Butz's team scrambled to figure it out.

The pictures and video were terrifying: gridlocked cars trying to drive through showers of glowing embers, blinding smoke and flashes of white-hot flames.

Allen and his crew started to talk about evacuating more people from town — which they described as not an easy decision.

"What people don’t realize is when you evacuate communities, there is just as many people saying, 'Why are you evacuating? I’ve lived here 30 years, I’m fine,'" Allen said. "There was lot of pressure around whether we’re doing the right thing or not."

The fire made the decision for him. As it burned through Abasand, it stretched a finger toward the water treatment plant and the bridge. Without the plant, there would be no water for the firefighters. Without the bridge, there would be no road for crews to travel back and forth on — or for people to escape.

"I call it the three-headed monster, because it had a life of its own," Bendfeld said. "It was like a living, moving thing. It was going east, it was going south and it was going north on us."

The next step was simple.

"Now it’s time to evacuate. We’re done."

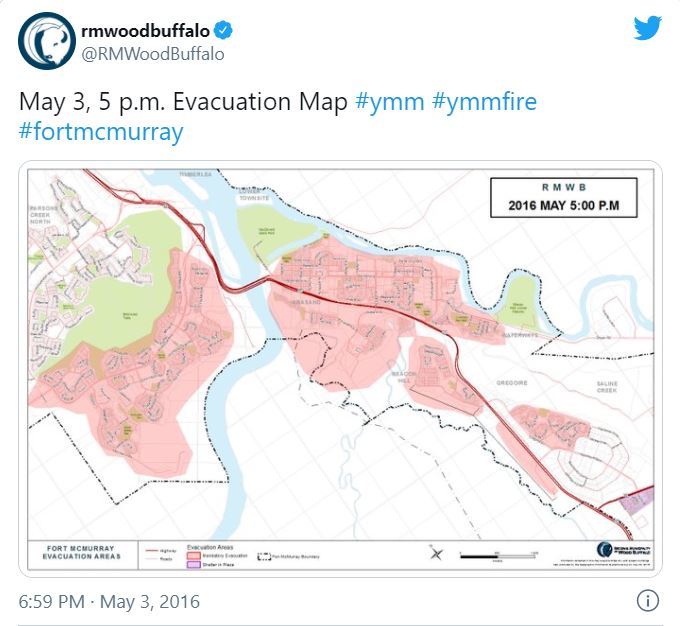

At 1:55 p.m., the City of Fort McMurray tweeted a voluntary evacuation notice for Abasand, Beacon Hill and Thickwood.

"Residents should be ready for mandatory within 30 minutes notice," it said. Many were already running from flames in their backyards.

"We evacuated lower Thickwood," Allen said. "So now we are struggling with, 'Where’s it going to go?'"

He remembers hearing that Centennial Trailer Park was gone. That the Super 8 motel at the edge of the city was gone. That "propane tanks were exploding and going up like missiles."

"I was freaking mad at it — pissed off," Allen said. "This fire is all around us. It just seemed, whatever we did, it just laughed at us and did something else."

It seemed luck was the only thing that would help them get people out of the city without someone dying.

To Bendfeld, that problem was a math equation – and he believed he knew the right answer.

There are no major towns north of Fort McMurray. And there is only one road out. To reach safety and services like hotels and gas stations, evacuees had to take Highway 63 southbound.

That would bring them to Edmonton, to Calgary. And now that the fire had forced the closure of the Fort McMurray airport, it would also take them to planes that could fly them to family out of province.

It soon became clear, though, that if everyone took the same route, the traffic jam would be deadly.

To Bendfeld, the problem was a math equation – and he believed he knew the right answer.

"You have to look at time and distance," Bendfeld said. "How many vehicles do we have? Highways and bridges only have so much capacity. Our primary task is getting everyone from the lower townsite, Abasand, Beacon Hill and Waterways out. And I can’t do that if I’ve got thousands of vehicles coming out of the north."

To see for himself, Bendfeld left the emergency operations headquarters and took another drive toward Abasand. What he saw was both horrifying and heartening.

Abasand was on fire. Cars and trucks were jammed on a road beside a huge wall of flames. Traffic was hardly moving — but drivers were still letting each other onto the road.

"I thank God for the people of Fort McMurray," Bendfeld said. "You’d think in an emergency like that it would be, 'Me first, don’t worry about anybody else.' But they weren’t. No matter how great a threat it was, they were letting people in."

Even so, Bendfeld knew the line of traffic would soon choke to a standstill. Simple math.

They needed to split the city’s escape route, using the Highway 63 bridge over the Athabasca River in the middle of town as the dividing line. He sent anyone north of the bridge north on Highway 63, and anyone south of the bridge south on that same road.

"We had no idea where we were going to send them when they went north," said Allen. "I remember initially thinking it was not a great idea. And then I remember thinking, that’s genius. This gives the most people the best chance of surviving. Because right now, I’m concerned we’ll have vehicles on the road on fire."

They knew camps north of Fort McMurray had enough food and shelter for thousands of oilfield workers so they could likely help residents, too. And it would give people in the south the best chance to get out alive.

The blaze kept flaring forward on the north side of the river. Butz’s worst fear was that the giant fire front his scouts had seen would sweep through Thickwood into a large wooded trail system called the Birchwood trails. If it did, it would be like igniting a massive cache of explosives.

"You go into survival mode," Butz said. "Here’s a problem. Here’s a solution. Then next, then next, then next."

His own home was in Thickwood. Having heard the rumours that spread almost as quickly as the flames, his wife Krista phoned. Butz said it was the first time he "got the sense of the panic around the city."

He told her not to worry, to lock down the school where she was working, and to stay there with their two boys. There wasn’t time to tell her much else.

"Be strong," he said.

Minutes later, his son Wesley sent a text message.

"Is the fire east of the golf course … toward the house?" the 15-year-old asked him. Butz knew it was going that way, but had no idea where exactly it would end up.

He didn’t want to lie. And there was no other way to reassure him. All he could do was tell Wesley what he told most of his firefighters that day.

"It’s coming," he wrote. "Be brave."

3:52 p.m.

The fire started to snake downtown. Officials put a notice out to all of Fort McMurray to get ready to leave.

Air crews dumped retardant on the Northern Lights Regional Health Centre after the blaze crept down Hospital Road. It burned at least one house there that day.

Vehicles were stuck in gridlock. Families watched flames beside the road. People wanted to go home, to collect a few things. To pick up their children from school. To get out.

"I was watching a fire that was going across the trees," Bendfeld said. "It was moving at 28 metres per hour. Then it was going at 32 metres per hour, then 300 metres per hour. That’s an astronomical difference in its characteristics. And it was just self-feeding. How do you get a hold of that?"

By the time Allen’s team made one plan, things changed so much that they needed a new one. They couldn’t keep up. It felt like they were losing. Everywhere.

"You’re praying that everyone got out," Butz said. "But it’s too early in the game to even do a search for people. We were evacuating. But you just had to assume there were going to be casualties, and that whole neighbourhoods were gone."

Abasand, Beacon Hill and Waterways — Fort McMurray’s original town site on the edge of downtown — were all on fire. That’s all anyone could tell him.

"That was overwhelming," Butz said. "But is there something you can do about that? No. What you can do is put out the fire. That’s the best you can do. You can evacuate the people, protect the property. That’s the best that we can do. And that’s what we were doing."

Crews held back the flames at Hospital Road. And they changed their entire approach, from "drop everything" to what Butz called "bump and roll."

They couldn’t stay until every fire was completely out. Because new ones were always starting. The firefighters were constantly looking over their shoulders. They had become both the hunters and the hunted.

5:30 p.m.

Most of Fort McMurray was ordered to leave, and as residents left, the city lost its eyes. Other than those 152 firefighters and their colleagues from oilsands, there was no one to notice the flames and sparks. Their 911 system was basically broken.

Indeed, the biggest threat now was those embers — millions of sparks raining into downtown, into Thickwood. They started smaller fires all over.

"You have to pick up, move on, pick up, move on," Butz said.

Trucks and firefighters roamed the city. They battled in neighbourhoods north of the river: along Ermine Crescent, Signal Road and the tip of Wood Buffalo. But the Beast was sneaky.

The fire flanked crews in the northwest, looping around to eat up houses behind them.

"We found this out because Timberlea sector command drove over to check things out and said, 'Hey guys, there are houses on fire behind you,'" Butz explained. "That scared me. Because no one could predict that. We thought we were holding our ground."

Trapped. Blind. With dwindling resources.

But none of the firefighters thought of quitting. No one joined the line of cars driving away from the inferno. Instead, they stood in the water and the soot and did what they had to do.

They tried not to think about their own homes, which were probably burning, or whether their families had escaped. They breathed toxic smoke. They developed blisters and trenchfoot. ("Baby powder, duct tape and put your sock over it and back out you go," is how Butz described the situation.) When a hydrant ran out of water, they grabbed fire extinguishers off the back of industrial oil trucks or used pails of water and mops.

One of the longest-held watches was at Fire Hall No. 1 downtown. A steady torrent of embers fell on the roof, but the crew doused them every time. Butz and his cohorts knew if they lost a fire hall, his team’s morale would plummet even more.

"They’re mopping houses, whacking at embers. Sometimes that’s all they had," said Butz. "It’s unmeasurable the amount of work that these guys did. There was no quit in them. That’s what saved the city, that first night."

They had won. They had saved 85 per cent of the town. But they didn’t know it then.

At the time, it didn’t feel like a victory at all. It felt like an ass-kicking. Each firefighter remained focused on the battle in front of them — the house they couldn’t save. To them, it seemed like the whole city was burning.

As the dark deepened, there were fewer and fewer civilian vehicles on the road — only emergency crews. Evacuees had gone north or south, as they had been told to do. Bendfeld and his crew arranged city buses to pick up the stranded, who had run out of gas and abandoned their vehicles on the side of the road.

At 11 p.m., he took his first break in 72 hours.

His elderly mother and stepson had found a ride to the parking lot outside the emergency centre and were waiting to see him.

After hugging them both, he wrote in his military log book for the first time that day: "Everything’s alright, through here."

Darby Allen, on the other hand, struggled in the dark.

For days he had played a game of chess against the nastiest opponent imaginable. While he was in the middle of it, all he could think about was winning. He focused on the maps and predictions and moving pieces around.

In the quieter moments, the reality loomed. This was no game. Those chess pieces were people.

As the fire settled into its nightly rest, the quiet grew too loud for Allen. And so did the questions. Did he make the decision to evacuate too late? And at what cost?

"I really believed at the end of Tuesday, if we wake up at first light and we’ve got 50 per cent of our homes left, and we’ve only killed a few thousand people, we’d have done well. That’s how bad I felt," Allen said. "You’re basically running on adrenaline. You just can’t let your emotions get the better of you. What you really want to do is sit down in a chair and hug your mom or your wife and say, 'Make this better for me, please.' But nobody can make it better for you."

Late that night, during one of those moments of calm, Allen and Bendfeld went outside onto the fire hall balcony. There in the dark, with the roads clear and the fire still burning around them, Allen lit a cigarette.

The ash glowed as Allen took a breath. They could see the flames rage on in the distance. After a few deep drags, Allen spoke for the first time about his fear.

“Mate, I don’t know if we made the right decision,” he said in his deep British growl.

“I don’t know. We did what we had to do, I guess.”

“Well, maybe we’re both fired.”

“Maybe.”

Postscript

The magnitude of what they actually accomplished during that mass evacuation would not sink in until weeks later.

In the first 24 hours, they fought without much outside help. Before the Alberta government declared a province-wide state of emergency and took over the leadership of fighting the fire, before extra firefighters from other cities or countries arrived to help, this small group did a huge thing.

They safely evacuated more than 90,000 people from an isolated northern town — out of one road. In the end, they lost roughly 2,400 structures, only about 15 per cent of the town.

At the time, however, Darby Allen and the team that worked through the first night believed most of Fort McMurray was gone. When morning came, they expected the phones in the emergency centre to start ringing with reports of bodies found in burned-out cars and houses.

But they didn’t.

"That lifted a massive weight off my shoulders," he said.

That was the first proof that his decision to delay the evacuation hadn’t killed anyone. Something he thought was statistically impossible.

"We don’t give a shit right now about anything else. We need to save the people," he said, talking about his feeling at the time. "Preservation of life, critical infrastructure, the rest of the infrastructure: That’s what we did for days and days and days."

That battle against the wildefire continued for many days. On May 4, the fire burned dangerously close to the water treatment plant. They held it back. Flames also tore into Prospect Point on the north side, destroying most of that neighbourhood. The wildfire threatened the airport and burned right to the edge of the emergency operations centre itself.

Some have questioned Allen’s leadership. Some say his team should have evacuated the town sooner. The provincial government has now opened a formal review of what happened, with answers expected by year’s end.*

What everyone seems to agree on is that the fire Darby Allen, Jody Butz and Dale Bendfeld faced was extreme, and may change the way scientists study such events.

At its high point, the Beast travelled at a rate of 30 to 40 metres per minute and created its own weather — a black funnel cloud at the heart of the fire grew so large it could be seen from space.

In total, the Fort McMurray wildfire burned an area of 589,552 hectares, or 365,522 soccer fields. Its largest perimeter was 1,080 kilometres.

The cause is unknown. But officials have ruled out lightning and say it was likely caused by human activity.

It wasn’t until June 1 — one month after the fire was first detected — that authorities let residents go back home to Fort McMurray. On July 4, the fire was officially deemed "under control." But firefighters say it will likely take until summer 2017 to extinguish it completely.

More than 90,000 people were evacuated from their homes on May 3, the largest prolonged evacuation in Canadian history.

No one died in the flames.**

No one died in the flames. It took weeks for Darby Allen to believe that.

It took weeks for Darby Allen to believe that. And even now, the peace is uneasy.

He may have led one of the biggest evacuations the country has ever seen, but he’s also just a guy in a firefighter’s uniform. A guy who, on some level, may always expect to find out he lost one of his people to the Beast.

A guy who’s still uncertain whether he and his team did the right thing at every turn, but believes they did the best they could.

And knows they were lucky.

"I am not a religious man, but it was a little bit of a miracle."

* CBC made multiple requests for interviews with provincial wildfire manager Bernie Schmitte and Chad Morrison, who took over the emergency operation on May 4. Those requests were declined. A provincial spokesperson said they cannot talk about what happened on the day of the evacuation until after a review is complete.

** Emily Ryan, 15, and her cousin Aaron Hodgson, 19, died in a head-on crash on May 4 as their family fled the fire on Highway 881.

This story was originally published on July 27, 2016. It was republished in 2021, after the original page was broken due to a technical error. The timelines and details described are based on several hours of interviews in June 2016 with the three men featured, and confirmed through official documents, supporting interviews, verified social media posts, and firsthand witnesses. The wildfire was officially declared extinguished on August 2, 2017.