December 2, 2018

The last thing Reina Gladys Guevara’s daughter told her was a lie.

It was a Friday evening, and her daughter said she was going to the textile factory in Tegucigalpa, where they both worked for $5 a day, to pick up her weekly pay.

That was 18 years ago.

“I waited for her, but she never came back,” said the 62-year-old Guevara, who has a steely gaze, with lines on her face reminiscent of a road map.

Guevara’s teenage daughter had left behind her two-year-old son and her possessions to make her way into Guatemala, then Mexico and finally the United States, alone and illegally.

I spoke with Guevara in northern Honduras, in the middle of a museum — a memorial to a railway that never really was — trying to understand the rough roads her life had taken.

This year, thousands of Hondurans joined caravans trudging toward the U.S., seeking an escape from misery.

President Donald Trump has called the migrants terrorists, “stone-cold” criminals and invaders. Some migrants were tear-gassed in a clash with U.S. agents when they rushed the border last week.

I was born in Honduras, a country smaller than Florida in the heart of Central America. As a child, I explored every corner of it. I walked through the towering Mayan pyramids and snorkled around the world’s second largest coral reef. I painted murals on the chipped walls of Tegucigalpa, the capital.

And I observed the city’s extremes. Blue-glass modern buildings reflecting sunlight on grimy, small houses below, mashed together like sardines in a can. An ice-cream seller ringing the bells of his shabby cart, as an SUV hurtles through stop lights, aided by sirens bought off Amazon.

As I grew up, my country was struggling under government corruption and crime, and I said goodbye to it in 2013, when I left to study journalism in New Brunswick.

But reading about Honduras this year from a distance, I had questions — questions that news stories didn’t seem to address: Why is there so much misery in a country so beautiful? Is there any reason to hope?

I went back to Honduras to try to find out, to talk to ordinary people touched by the migration and to experts who’ve tried to understand it.

“They don’t do a damn thing for us,” Trump told supporters recently about Honduras and other Central American countries.

Does he know, I wonder, what Americans have done in Honduras?

The Banana Man

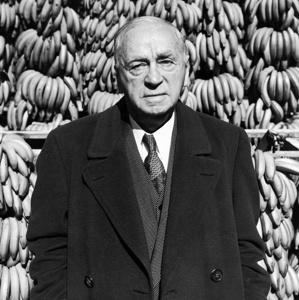

Samuel Zemurray’s first job in the U.S. was as a chicken catcher for a peddler in 1892. He was 15, had just moved to Alabama from Russia and was earning about 10 cents a day.

Four years later, Zemurray was in Mobile, Ala., paying next to nothing for overripe bananas shipped from Central America and selling them to local customers.

Sam the Banana Man, as he became known, eventually established his own import business in New Orleans and bought thousands of acres of fertile Honduran land, near the Cuyamel River on the northern coast, to grow bananas.

For the most part, the land was jungle, but the high temperatures, rainfall and rich soil made it perfect for the tropical fruit.

Zemurray’s Cuyamel Fruit Company and other U.S. businesses in Honduras went to great lengths to expand their riches.

In 1911, Zemurray wanted more from the government. With Manuel Bonilla — once the Honduran president but now flat broke in New Orleans — he hired a small army, bought a battleship and sailed to Honduras.

“Manuel Bonilla became the Honduran president once again, in 1912, with fraudulent elections, but the one making the decisions was Zemurray,” said Claudio Salgado, an economics professor at the National Autonomous University of Honduras.

The Bonilla government gave Zemurray tax-free concessions, loans and more coastal land.

For the first decades of the 20th century, bananas dominated the country’s exports, and U.S. interests dominated bananas. Honduras was the quintessential banana republic, the disparaging term for small nations ruled by oligarchs and utterly dependant on one crop.

A walk for a wage

Raymundo Cruz was 18 when he heard about the plantations. By then, the American-owned United Fruit Company had absorbed Sam the Banana Man’s operations.

United Fruit, now Chiquita, was hiring, giving workers a place to live, free education for their kids and a regular wage of about one to four dollars a day.

“He’d tell us about when he walked from the south coast to the north just to work on the banana plantations,” Gisela Cruz, manager of Progreso Railway Museum, said of her father. “Thousands did the same. They moved north.”

Raymundo walked more than three days to reach the Tela Railroad Company, the distribution arm of the United Fruit empire.

“They brought some economic progress ... But workers were basically slaves.”

Although still a banana company, Tela Railroad stuck "railroad" into its name in deference to the dream of every Honduran government: a railway connecting the Caribbean and the Pacific, running from Punta Castilla in the north to Amapala in the south and propelling Honduras into the world.

Too poor to build a railway, Honduras turned to the U.S. companies, selling land concessions of up to 99 years and allowing the companies to do as they pleased in exchange for rail.

“The banana companies were known as ‘the state within the state’ due to their control,” Salgado said. “They brought some economic progress, as they built schools and hospitals in areas.

“But workers were basically slaves.”

On the plantations, people worked long weeks and slept in hammocks and cots, said Darío Euraque, a Honduran native and professor of Latin American history at Trinity College in Connecticut.

Their crowded wooden barracks had no toilets, drains or interior walls and swarmed with mosquitoes.

The companies operated their rail lines mostly for their own needs, and no track ever reached inland to Tegucigalpa. But the trains also became transportation for people and ideas and for organizers of the biggest protest in Honduran history, Euraque said.

Half a century after the banana companies began wielding their extraordinary power, workers took to the streets in a strike. In 1954, cities fell like dominoes as employees left assembly lines to join the protest.

The strike lasted two months and brought about social reforms. Wages and hours were now fixed in contracts.

“The right to strike, the right to have a certain degree of medical attention at clinics or hospitals, that’s what was fundamentally different,” Euraque said.

A lost way of life

I was headed north toward the coast when I stopped at Progreso Railway Museum, an hour’s drive from old plantations.

As I walked into the yellow building, I was struck by the black and white photos of a railway that, to me, had seemed more myth than real.

Gisela Cruz was sitting in her air-conditioned office while the temperature outside hit 35 C.

She offered to hop into my car and show me where she grew up, where her family’s history became a story of flight.

“For every family that you meet on the banana fields, there are two or three members who’ve left to the United States,” she said. “I have five brothers, and three of them are gone.”

“Politicians saw development not as something that could be done by Hondurans but as a way to negotiate with U.S. corporations.”

Cruz, who was born long after the strike, described life on the plantations as idyllic.

She played in the fields with other workers’ kids, while Raymundo, her father, toiled under the sun with a pillow on his shoulder.

“He’d shake the banana plant and the [bananas] would fall down, right on the pillow,” she said.

But as operational costs went up because of the reforms, the banana companies began moving to Ecuador, where workers earned lower wages and no benefits.

The Honduran railroad dream collapsed. United Fruit even ripped up its track and took the steel to Ecuador, according to Euraque.

Bananas’ share of exports dropped from almost 80 per cent to about four today as the economy diversified. Now, coffee and knit shirts are the leading exports, he said.

The banana industry left a mixed legacy, economists said. It helped the economy — and what’s left of the industry still does help, according to Prof. Hugo Noé Pino of the National Technological University of Honduras.

“But the way in which it occurred in Honduras, as an enclave of political power, I would say, overall harmed the country more than it helped,” said Noé Pino, a former senior adviser at the World Bank.

Euraque said the banana sector created a mentality of dependence on foreign corporations and on corruption.

"Politicians saw development not as something that could be done by Hondurans but as a way to negotiate with U.S. corporations. That continues to be a problem today."

A punishing storm

In 1998, Mitch, the deadliest hurricane in the history of Central America struck, making 20 per cent of Hondurans homeless.

Chiquita’s remaining packing plants and banana trees washed away. The company rebuilt only half of what was lost, so thousands of workers lost their jobs.

Working on plantations had been the only option for many uneducated Hondurans. Now workers from rural areas, including Reina Gladys Guevara, who worked in the fields for 20 years, headed to the cities.

But things haven’t been much easier there.

More than 55 percent of children enrolled in public schools — where teaching is a low-wage career — quit before the end of the primary level to work full time to support their families, according to the Honduran National Institute of Statistics.

Even educated, urban Hondurans can be forced to scrape together two or three jobs to survive.

The economic sectors that gained momentum after the hurricane, such as finance and energy, all have something in common, Noé Pino said.

“They create less employment than what the agriculture sector once did.”

And this lack of jobs with a livable wage has led to violent crime, he said.

“Unemployment with our growing population leads younger ones to join gangs and drug trafficking.”

By the turn of the century, the homicide rate was 86 per 100,000 inhabitants.

You could draw a line with chalk around the rich neighborhoods.

Going back to Tegucigalpa after two years away, I didn’t find things much changed, certainly not to the optimistic degree President Juan Orlando Hernández boasts about.

Divisions between rich and poor seemed as stark as ever.

From the cul de sac where my family lives, where the houses are average-size and some sport graffiti scribbles, and from the broken roads of Honduras’s poorest neighborhoods, you can look up and see mansions at the top of the hills.

Those houses tower above the city. They’re a reminder, some Hondurans think, of the power and money possible for people who tie themselves to government, work out tax-avoidance schemes, or move into the drug trade.

You could draw a line with chalk around the rich neighborhoods.

Stories of flight

Between 50,000 and 80,000 Hondurans leave every year from urban and rural areas, mostly the latter, according to Noé Pino.

Many have said they are escaping gangs, extortion and violence in the cities. But those from the countryside, where violence is less severe, are also fleeing for their lives.

These economic refugees have been denied jobs, food security and health, Noé Pino said.

“When the state, as happens in Honduras, is not able to fulfil those obligations, then the population can request to qualify as a refugee, based on something that threatens their life.”

Although the U.S. does not accept economic refugees, Hondurans are used to saying goodbye to people determined to find a better life somehow.

María Sánchez moved from the small town of Candelaria to Tegucigalpa in a desperate search for work.

“There’s almost no young people in my town,” said the 32-year-old Sánchez, who has a shy smile and bags under her tired, black eyes. “They all leave once they grow up.”

“He was in Honduras for less than a year before he was hiring another coyote to help him go again.”

She crossed paths with my family when my parents hired her as a maid and now works in a textile plant.

But her family still lives in Candelaria, where the adobe houses have hay roofs, their light-tan colour a contrast to the green fields around them. Sánchez’s family has a farm with chickens, pigs and cows, and most people there live on what they harvest.

Violence is not common, and you don’t have to hide your phone while walking on the dirt roads.

“But people would rather leave to search for a better future,” Sánchez said. “They don’t want to be farmers in a poor little town for the rest of their lives.”

Three of her brothers made it to the U.S. Her family helped one brother find a coyote, a smuggler who gets people across the Honduras-Guatemala border or the Guatemala-Mexico border, finds them food and shows them safe routes.

“My family was able to gather 50,000 lempiras ($2,500 US) through many loans, so we could pay a coyote to help my brother cross the border illegally,” Sánchez said.

Migrants who make it into the U.S. can earn enough money from bricklaying and other trades to send some back home.

Sánchez’s youngest brother was working as a bricklayer when he was caught driving without a licence and sent back to Honduras in 2013. His daily pay dropped to $12, from the $100 he made in Houston.

“He was in Honduras for less than a year before he was hiring another coyote to help him go again,” Sánchez said.

The family hasn’t heard from him since, and the other brothers in the U.S. fear giving away their illegal status trying to find him.

“Me? I never thought of leaving,” Sánchez said. “I’m too scared.”

No role models

Noé Pino believes change can only come to Honduras if honest people take control.

But role models are hard to find, he said, when the government is susceptible to bribes and has a history of caring less about people than business, whether it’s bananas or a massive hydroelectric dam.

“This is what we’ve seen with every government,” he said, adding that the Guatemalan government next door bows to Canadian mining interests in a similar way.

Democracy in Honduras has taken a battering over the years, often with help from the U.S.

Nine years ago, after some reforms, then-president Manuel Zelaya wanted a referendum on a proposed constitutional change that would allow a president to seek a second term.

The military, which had run the country a few decades earlier, seized Zelaya in his pajamas and flew him to exile in Costa Rica.

Barack Obama, the U.S. president at the time, condemned the coup, but his secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, rather than pressing for the return of Zelaya, pressed for new elections. She believed the region didn’t need Zelaya, with his ties to Hugo Chavez of Venezuela.

Three years later, the “second Honduran coup,” as Noé Pino calls it, brought a different U.S. response.

In 2012, Hernández tampered with the top court, which then changed the constitution so a president could run for a second term.

“The U.S. validated the illegal re-election because of their ideological affinity with Juan Orlando Hernández,” Noé Pino said.

After Hernández won in 2017, people protested in the streets, although protest in Honduras is risky. Just the year before, environmental activist Berta Cáceres was slain.

The Indigenous woman was trying to stop construction of a dam in one of her community’s sacred rivers, when hitmen shot her in the chest at home.

Reina Gladys Guevara depends on the few hundred dollars a month she gets from the daughter who left 18 years ago.

Her daughter lives in California and works at a pizza restaurant and as a cab driver. She is trying to find a way to get her son to the U.S.

Honduran media outlets barely cover the migration to the U.S., but everyone knows about it, Noé Pino said. Initially, the caravans produced shock and an eerie disquiet among Hondurans.

We Hondurans are used to hearing stories of people fleeing in the dark. But what frightens us is seeing people depart in broad daylight. What frightens us is that the answer to the question I asked at the start of my trip — Is there hope? — might be no, that the only way out of misery really does lead out of the country.

But the caravan that has riled Trump may bring Hondurans together — to work on solutions of their own, Noé Pino said.

Mauricio Oliva, the Congress president, has even promised to ask Hondurans what should be done about the conditions driving people away.

“This is when the people must speak up,” Noé Pino said.

Euraque thinks the government should tap into the money sent home by many of the one million Hondurans living in the U.S., 60 per cent of them undocumented.

“That money could be used in more developmental ways than it tends to be used now, which is primarily to keep people alive.”

The youthfulness of the population gives him hope the political system will change.

“The changes required are going to take a long time, and we have very young people who can rise to the occasion.”

A glimpse of home

As I walked through Tegucigalpa near the end of my journey, I hid my camera under my shirt, always alert to the potential for robbery.

But when I got to the farmers market, I found myself shooting still after still, almost forgetting where I was.

All I saw were girls helping their mothers sell strawberries, mangoes, pineapples and melons, and boys piling bananas in the stalls. I took pictures of men helping old women with their vegetables and toddlers pointing at my camera in awe.

Through my lens, I saw working men and women, laughing and taking money out of their pockets without looking over their shoulders in fear first.

And it came back to me. I was home. And this was what home could always be like.