It began like any other Friday.

Liban Abokor, 33, was getting set to attend prayers when his phone rang. It was his friend calling to say this time he wouldn't be joining him. Instead, he was on his way to Toronto's west end to attend the funeral of a young Somali man killed a week earlier — the 14th such death in the city in just two years.

"From God we come and to him we return," Abokor replied, offering the words of condolence they had both heard so many times before. "It feels like another Somali boy is being killed every other day, right?"

"It's almost become routine. Another day, another janazah," his friend replied solemnly, using the Arabic word for "funeral."

That was February 2016. Seventeen-year-old Saeid Kaylie had been fatally stabbed outside the highrise where he lived in the west Toronto neighbourhood of Etobicoke, his family left to grieve the loss of a young man whose life had only just begun.

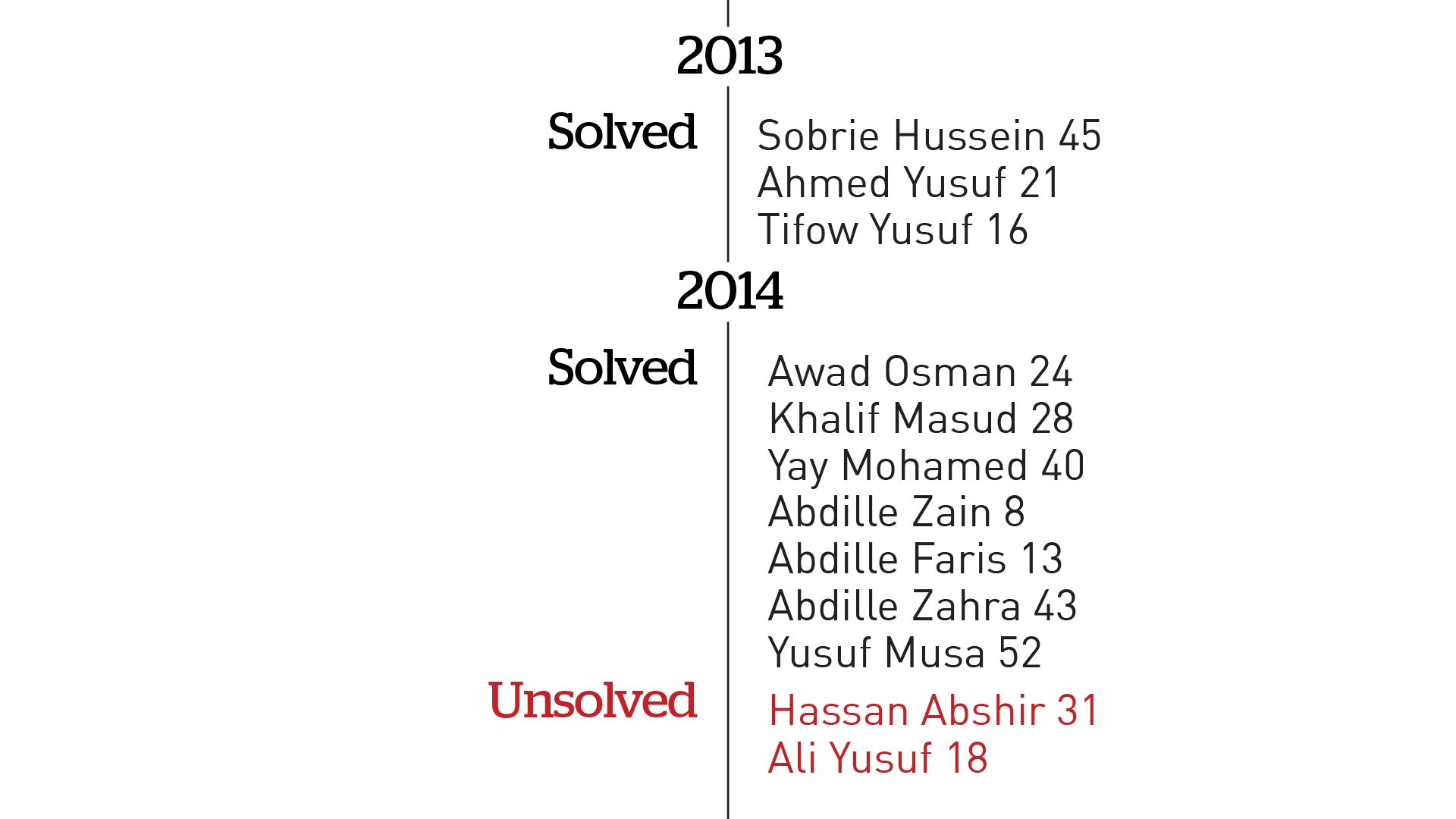

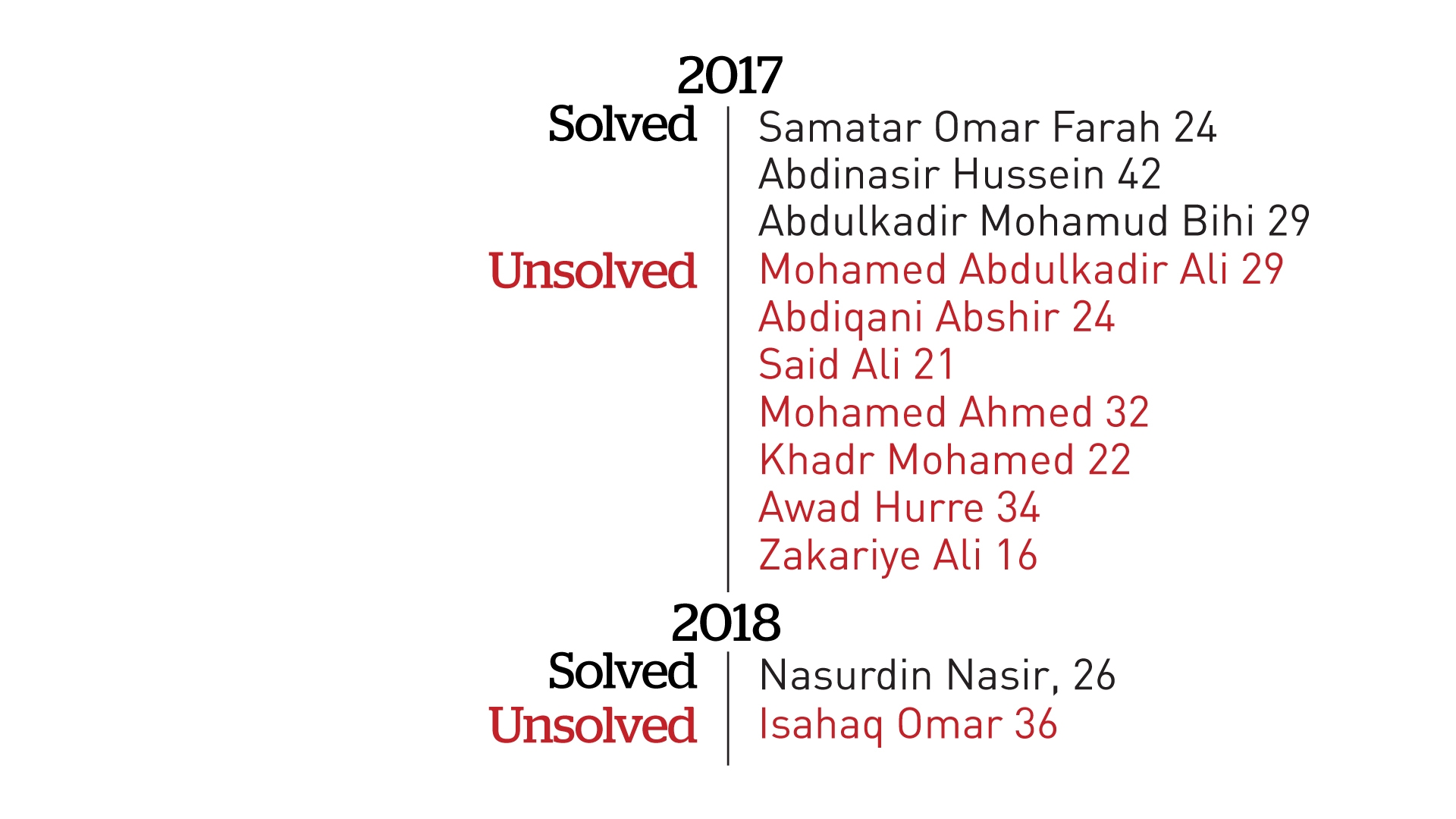

But while two teens were charged with first-degree murder in Kaylie's death, a new report reveals 45 per cent of cases involving Somali victims of homicide in Toronto between 2004 and 2014 remain unsolved, compared to an average of 30 per cent for homicide cases in Toronto overall.

Of those, the overwhelming majority of victims were young men under 30.

"These are Canadian-born kids who went to kindergarten here, drank soup from Tim Hortons and took the TTC to get around."

The troubling findings are part of a six-month long study by a Toronto-based non-profit organization called Youth Leaps that aimed to capture the toll the deaths have taken on the community. Together with Abokor, the group's executive director, the all-Somali research team worked to develop what they say is the first-ever database of the city's Somali homicide victims.

The hope, at first, was to find out why. What was behind the killings of these young men? But the researchers quickly learned that there was a more immediate set of questions to answer: Just how many of them were dying and who were they?

The Toronto Police Service does not track homicides by specific ethnicity. Instead, its records are broken down only by race: white, black, brown, Asian, Aboriginal and unknown.

With no available breakdown of homicide victims by ethnicity, the group relied on a combination of publicly available statistical data, police records, news stories, focus groups and difficult conversations with victims' families to produce their own data — the first step in what they intend to be a much larger investigation. In all, the researchers connected with over 300 Somali youth across Ontario.

"This report has not looked at who is killing who or even why," Abokor said, referring to the report summarizing their findings released Wednesday. "We didn't pathologize. I don't think we have enough data to do that yet."

"This was a starting point."

II.

The study makes some startling observations: Over a decade-long period between 2004 to 2014, Toronto grew significantly safer, with homicide rates dropping 12 per cent. Yet over the same period, the proportion of young Somali men among the city's homicide victims had climbed from 1.6 per cent to 16 per cent, a number that's disproportionately high for a community that represents less than one per cent of Toronto's total population.

Perhaps more alarming, Somali homicide victims are about 10 years younger than the national average age of homicide victims.

For the researchers, those statistics point to a disturbing trend: while Toronto was becoming safer overall, a crisis was quietly unfolding in the city's Somali community.

Just last year, Toronto was dubbed North America's safest city by The Economist magazine's 2017 safe cities index. The ranking came amid a spate of shootings in the community that cut two young lives short in a single week: that of 29-year-old Abdulkadir Bihi, a newlywed and soon-to-be father shot in broad daylight while visiting his mother and 16-year-old Zakariye Ali, fatally shot in an Etobicoke school parking lot.

Ali's case remains unsolved. But while two people were charged with 1st-degree murder last October in Bihi's case, a cousin of the victim who CBC has agreed not to identify says the family hasn't heard much about the progress of the case since and that justice feels far off.

Bihi's death is made all the more tragic by the fact that his first son was born just a month after he was killed and will never know his father, the 34-year-old cousin said.

For Abokor, the fact that most of the deaths involved young people flies in the face of a misconception he hears all too often: that the violence in the Somali community is imported into Canada by a newcomer population that fled war-torn Somalia. Instead, the victims are largely young men who were born in this country or have spent the majority of their lives here, he says.

"The evidence suggests that this is a Canadian problem, a Toronto issue," he said.

"This isn't an issue of a refugee or immigrant population that's having a hard time fitting in. These are Canadian-born kids who went to kindergarten here, drank soup from Tim Hortons and took the TTC to get around.”

In fact, it's been three decades since the first waves of Somalis migrated to Toronto, many as refugees having fled the civil war back home. After the year-long government assistance provided to refugees ended, many families found themselves caught in a cycle of poverty and lack of housing. With their permanent resident status pending, many were unable to obtain higher education and formal employment — a situation made worse by landlords not willing to rent to Somali immigrants, the study explains.

That left most with little choice but to opt for government-subsidized housing in low-income neighbourhoods, which, the study says, tended to limit the opportunities available to youth in those communities. Somali youth in such neighbourhoods became simultaneously targets of police scrutiny and victims of crime, the authors argue.

Yet the assumption is often that Somali-Canadian homicides are linked to gang activity even in cases when there is little evidence to back that up, Abokor says. Those assumptions, he argues, are often reinforced by media reports that describe victims as having been "known to police" or by the use of mugshots from unrelated events when identifying individuals in police news releases.

Asked about that practice, Toronto police did not respond.

Last spring, for example, Toronto police described the death of 24-year-old Samatar Farah as "targeted," a term those close to him said simply didn't square with the kind, loving and always-smiling young man they knew.

At the time, Imam Hassan Ibrahim of the Abu Huraira Centre, the mosque where Farah used to pray, demanded clarification about just what police meant by that term. "That, again, will send a signal that it's a gang violence issue, but that's not what we know of Samatar," he said.

Police would later acknowledge Farah had nothing to do with a feud that broke out in the Chester Le area before his death and that he had no involvement in any gang or dispute between rival gangs.

But the community knows it isn't immune.

"There was always this feeling in the back of our heads that it might happen," Bihi's relative said, recalling how his cousin "fell in with the wrong crowd" during his youth.

"But he changed his life completely, 180 degrees. And we thought that was the end of it."

Still, Abokor says,"this unsubstantiated link is commonly offered up as an explanation, directly or indirectly, for the murder of Somali-Canadians," creating a false perception that these are cases of gang members killings each other, evoking little public sympathy and as a result, he argues, little action.

III.

Another one of the study's more startling findings is that 75 per cent of its 80 survey respondents reported a direct connection to a victim of violence.

Among those those who reported having experienced homicides in their community, the largest proportion were in their early 20s, had lived in their neighbourhoods for more than 10 years, spoke English and held Bachelor's degrees.

And so while thriving on the one hand, Abokor says, "this is a community that's been living with trauma."

"It creates an idea of 'Who is next? When is it my turn?'"

Samiya Abdi, 37, knows firsthand how trauma ripples through the tight-knit community. A public health consultant and community advocate, Abdi previously worked as a case manager counselling young people and their families. She's seen how the loss of life of a loved one can lead to fear, anxiety and depression at a community level through what she describes as "vicarious trauma."

"I would say every household probably is touched directly or indirectly by the violence that is experienced by our youth," she said.

"As soon as you hear the name of who has been shot or who has been killed or who has been injured, you would find an association then with that person, and there will be a connection, so there's trauma again."

Abdi points out a lack of mental health services can make coping with loss even more difficult, recalling wait times for counselling running as long as eight months while she was a case manager. People in crisis simply “do not have the luxury of time," she said.

One of the most profound examples of the emotional and psychological cost of the crisis, Abdi says, came from a young man who told her recently that he had been to more funerals in the mosque than weddings.

"When you have a generation that is growing up to associate our community gatherings with the idea of loss of life — and not due to natural causes but at a very young age cut short through violence — it creates an idea of, 'Who is next? When is it my turn?'"

Since 2000, there have been more than 50 homicide cases in Ontario and Alberta in which the victims were young Somali men, according to the report.

But no matter where, the roots of violent crime across marginalized communities are largely the same, Abdi argues: poverty, discrimination and environments in which young people lose hope and don't find avenues to help them deal with the pressures they face.

"It was just a normal life - what we call amazing now, it's just sad. Because everyone else has it. It's a normal life."

And that discrimination can have a discernible impact when it comes to the job market for example, Abokor argues.

In fact, a 2011 report from the Wellesley Institute entitled "Canada's Colour-Coded Labour Market" found those who identify as black had an annual earnings gap of $9,101 compared to "non-racialized" employees.

In the course of their literature review of existing research into the influence of race and ethnicity on Somali youth's prospects, the report's authors found various studies suggesting that being at once black, Muslim and Somali compounded the discrimination youth face.

Along with racial discrimination, fractured relationships with law enforcement agencies also contribute to the community's sense of marginalization.

For many in Toronto's Somali community, and among the black population more broadly, the experiences of carding, stop-and-frisks and racial profiling are not far from memory. Many who live in Etobicoke's Dixon neighbourhood recall the series of 2013 police raids dubbed Project Traveller during which police sought to take down a violent gang they said had been operating out of the area, an event forever linked to the infamous video of former Toronto mayor Rob Ford smoking crack cocaine.

"We heard from grandmothers that they had guns pointed to their head," Fowzia Duale Virtue said, describing the raid at the time.

Given the stereotypes that come with living in neighbourhoods where crime has occurred, many in community have described feeling as though they live under an ever-present cloud of suspicion.

That feeling was amplified, many say, by the Toronto Anti-Violence Intervention Strategy, a controversial police unit to focus on areas deemed to be high-crime set up in 2006 after the so-called "summer of the gun" that saw, what was at the time, an unprecedented number of shootings in the city.

Critics of TAVIS say it increased tensions between police and residents of targeted neighbourhoods, many of them people of colour, because officers often used carding as a policing tool. The much-maligned practice is now prohibited in many circumstances under provincial law.

The program was dismantled in part because, as Toronto police spokesperson Meaghan Gray put it, it resulted in "unintended impacts on communities, especially among racialized youth (including Somali youth), who felt unfairly targeted."

Abdi argues that some young people's loss of faith in the justice and law enforcement system has been exacerbated by the number of homicide cases in their community that remain unsolved and has, in some cases, perpetuated a cycle of crime and violence.

"If young people trusted the system, if young people knew that justice would be served, then they would not be tempted to continue that cycle and to take matters into their own hands," Abdi said. "But the fact that these cases continue to go unsolved … this could be one of the reasons why young people might feel that this is their only way."

Gray says the force doesn't prioritize cases based on ethnicity, race, socioeconomic status, gender or other demographic factors.

"Every case is different," she said, adding many factors affect how quickly each can be resolved.

"However, it is always concerning to us when any one particular community feels that they have not received the level of policing services that they should expect."

It's for that reason that she says police engagement with the community is so important.

That engagement includes public information sessions, ongoing communication and collaboration with mosques, community leaders, Somali mothers, participating in youth programs, working with a grassroots groups such as the Somali Canadian Forum.

"We must consider the lived experiences of those we serve if we’re going to be successful at creating a partnership based on mutual trust and respect," said Gray.

IV.

It wasn’t always like this, Bihi's cousin says.

"It was amazing," he said, recalling a childhood in Dixon when he wasn't afraid to walk around in his own neighbourhood. "It was just a normal life — what we call amazing now. It's just sad. Because everyone else has it. It's a normal life."

"There is a generation of brilliant, young physicians, and engineers, and lawyers, and artists that are really making a beautiful difference in this city."

A normal life is what his family sought when they decided to leave Toronto for Mississauga in the late 90s, a time when he says drugs were finding their way into the neighbourhoods where so many Somalis were living. It was, as he puts it, "the beginning of the end" in his Dixon neighbourhood.

Those who could, he says, moved away. And even now, all these years later, he says he keeps his distance from the area, refusing to go there — not even to see family.

"I grew up in a different time, a different era. It was nothing like this," he said. "I studied my first year of high school there, Scarlett Heights, and I lived in Dixon all my life. And it was beautiful... I lived in a golden age for the Somali community at that time."

But for Abokor, leaving isn't the solution.

Having moved to Toronto from New Jersey around the age of four, he remembers wondering what had happened to the sound of the sequence of locks his mother would turn, to which he'd grown so accustomed when living in the U.S.

"At night time, we would hear all of those locks closing. When we moved to Toronto, there was this missing sound that had almost become a lullaby," he said.

Toronto was different, he remembers being told. They only needed one lock here. But as he soon found out, that wasn't the case for all.

For certain populations, particularly Black Canadians and, in his case, Somali Canadians, he learned, "the relative safety of Toronto doesn't necessarily translate." Nevertheless, many of those surveyed in the study reported feeling strongly connected to their neighbourhoods, saying they looked to themselves first when it came to taking responsibility for a brighter future.

“There is a generation of brilliant young physicians, and engineers, and lawyers, and artists that are really making a beautiful difference in this city and are actually changing the culture, and really impacting how Toronto is formed,” Abdi said.

Abokor agrees.

“This isn’t a community that's seeking a handout,” he says. “There’s no shortage of compassion and care and angst and concern in the community. And there’s no shortage of effort, but there is a shortage of support.”

Still, he worries about the perception some hold that any solutions now are too little too late.

"I don't want to believe that," he says. "And I don't think our young people can afford to believe that either."