May 10, 2020

David McLaren's mother was sick with the flu when she gave him a bottle of Aspirin and told him to take it to a nearby family that had been cut down by multiple diseases sweeping through the Upper Ottawa Valley.

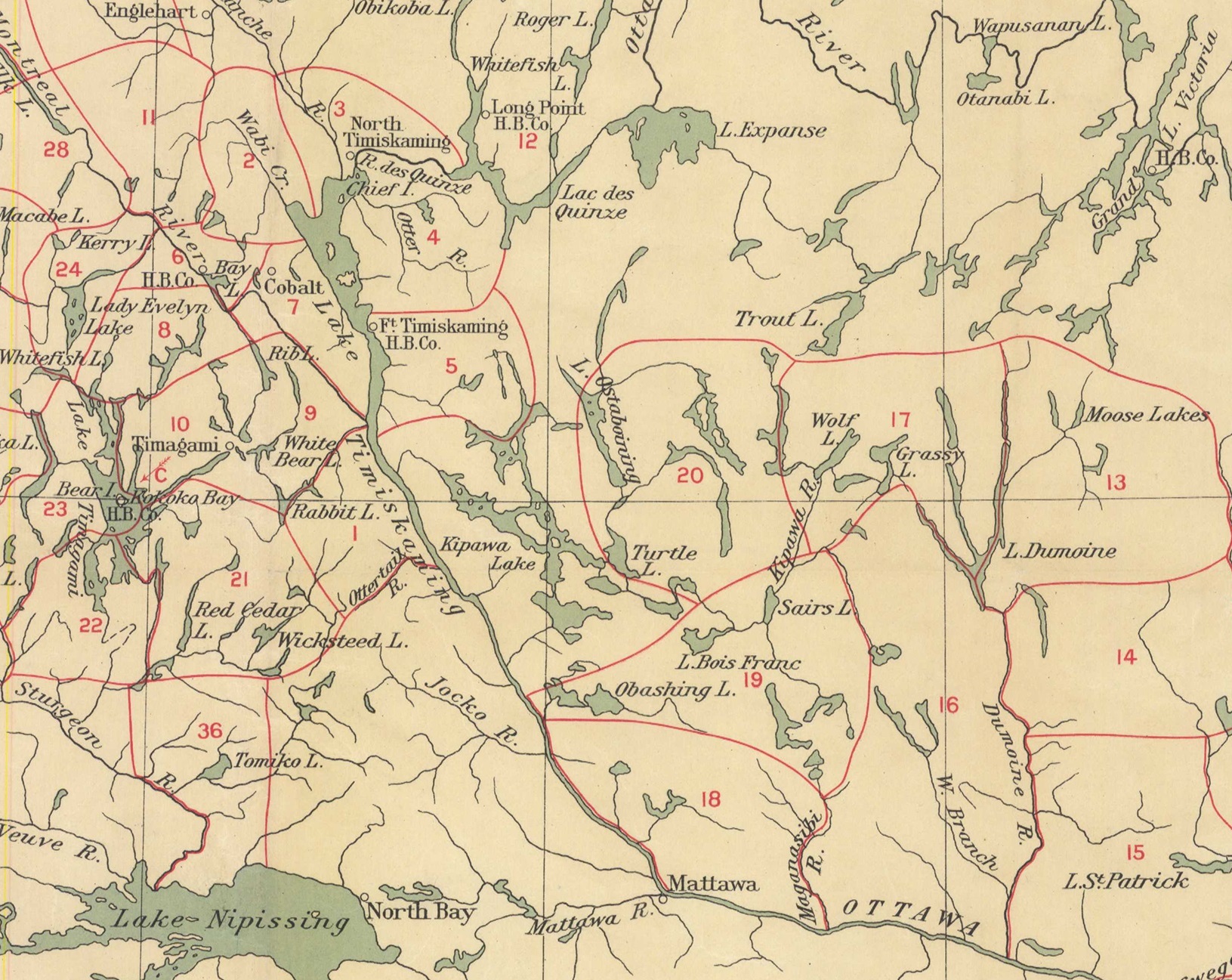

It was 1931, and measles, chicken pox, tuberculosis and influenza gripped the Sand Point Algonquin settlement of about 350 people by Lac des Quinze, about 450 kilometres northwest of Ottawa.

Most of the people at Sand Point were sick, some were dying, and McLaren’s mother, Elizabeth, who was a teacher in the village, couldn’t find a doctor to come and help.

“There was an epidemic all over,” McLaren, an Algonquin elder, would later say in a 1996 interview with researchers for the Algonquin Nation Secretariat.

“All the doctors were tied up ... nobody could come. At every place, this flu. But now, the measles was deadly to the Indians, along with the flu.”

So McLaren, who was 15 at the time, took the bottle of Aspirin and arrived at the family’s plywood shack where a young man, maybe a year or two older than him, was lying by the door.

“He was all broke out,” said McLaren.

“He died a few days later.”

The father of the family was in another bed, and the mother was struggling to take care of them along with six-year-old twins.

“The mother was crawling from bed to bed,” he said.

Nine people died that year from the epidemic, said McLaren.

“Everybody was sick," he said. "There was about two guys that were cutting wood, but then they had to make coffins and bury the dead."

Families wiped out

From the 1830s to the 1930s disease swept the Upper Ottawa Valley in successive epidemics through Algonquin settlements — wiping out whole families and villages. Loggers, fur traders, miners, labourers and settlers introduced the diseases to the Algonquin, forever reshaping their communities.

Throughout the 1900s, it was tuberculosis that afflicted Indigenous communities, aided in its spread by residential schools.

This was a story repeated over and over since Europeans first set foot on the hemisphere, triggering waves of epidemics over the centuries that sometimes wiped out whole nations.

Now, much of the world is in the grip of the COVID-19 pandemic that has forced entire countries, including Canada, to go into varying stages of lockdown.

“The broader Canadian population, for the first time since the Spanish flu, is experiencing what Indigenous communities have experienced throughout their entire contact with Europeans,” said independent researcher and historian Jim Morrison, who conducted the interview with McLaren, now deceased.

“It’s something every generation of Indigenous people faced in various parts of Canada.”

No immunity

The Algonquin in the region had little contact with European settlers, beyond fur traders, before the 1830s, and no immunity to the types of diseases that would soon sweep through their lands, according to the Algonquin Nation Secretariat’s research. By the 1840s, an influx of forestry labourers and Irish settlers brought some of the first waves of scarlet fever, measles, scrofula and tuberculosis into the Upper Ottawa Valley.

When Father R.F. Laverlochere arrived in the area in May 1848, he was met with what he described in a letter as a “sad spectacle” of “walking skeletons” with “death in their heart” who were waiting for the “arrival of black-robes to die.”

Writing to the Bishop of Bytown, Laverloche said the Algonquin were in “frightening misery that decimated daily” caused by tuberculosis, and he could do little to alleviate their physical suffering.

“The missionary, himself often deprived of the strictest necessities, cannot nevertheless help but share his piece of dried biscuit with these poor emaciated people,” wrote Laverloche.

The turn of the century brought little respite to the Algonquin of the region. In 1907, a typhoid outbreak linked to unsanitary and overcrowded conditions in camps around Cobalt, Ont., about 140 kilometres northeast of Sudbury, swept through the region.

In 1911, a labourer working on a dam at an outlet of Lac des Quinze introduced smallpox into the area, which spread into the town of North Temiskaming and the Algonquin reserve of Timiskaming. Six houses were quarantined as a result, according to the research.

'Bad spirit'

Even before the Spanish flu arrived and ravaged Algonquin settlements in the Upper Ottawa Valley, they had already suffered waves of infectious disease with measles, influenza, smallpox, typhoid, tuberculosis and scrofula — a swelling of the glands caused by tuberculosis bacteria.

In the early 1900s, a tuberculosis epidemic followed by smallpox hit Algonquin villages in and around Wolf Lake and nearby Grassy Lake, around 200 kilometres west of Témiscaming, Que.

Between August 1905 and 1906, tuberculosis wiped out families and emptied villages. Mission records examined by the Algonquin Nation Secretariat showed that at least 18 people from eight families in the Grassy Lake and Wolf Lake area died. The historical record said they were all buried at Grassy Lake.

“I remember people coming to tell my mother of families dying all over the bush,” Frank Robinson said in an interview recorded by Kermot Moore, author of the 1982 book, Kipawa: Portrait of a People.

Robinson, who had mixed Algonquin ancestry, was born in 1900 and lived at Wolf Lake.

“I don’t remember anybody ever saying how many died. When they talked to my mother, it was about the people who were left, the kids.”

Robinson said that the villages at Grassy Lake and Watson Lake, roughly 200 kilometres south of Rouyn-Noranda, Que., were wiped out and the abandoned houses eventually torn down for firewood.

“There was nobody living there. They were pulled apart, too, by trappers and lumbermen passing though, to make fire with,” said Robinson, according to the transcript contained in Moore’s book.

“Everybody believed in the Manido Wig-u-Wam then. That’s a bad spirit like a devil or something. They thought the Manido Wig-u-Wam come into their homes to kill them. Nobody ever lived there again.”

The waves of diseases forced the survivors to regroup at Wolf Lake.

Haunted by the Spanish flu

The Spanish flu killed about 65,000 Canadians and did not spare First Nations. The Department of Indian Affairs 1918-1919 annual report said mortality rates were higher in remote communities.

“It was impossible to secure adequate medical attention to the Indians living in the more outlying parts,” said the report.

There is a sugar bush — an area of maple trees used for syrup production — northeast of Témiscaming, by Ross Lake, that the late Peter "Falday" Hunter said he avoided because of the spirits from people buried there from an Algonquin settlement that was wiped out by the Spanish flu.

“You go there and you get kind of haunted,” said Hunter, according to audio from a 1995 interview with researchers from the Algonquin Nation Secretariat.

Hunter was born at Wolf Lake in 1921, and his grandmother was a member of the Whitebear family from Temagami.

He said one day he was hunting in the sugar bush and shot a white fox.

“I shot it right clean through and he never died. He run away,” said Hunter.

“Not a drop of blood. So that was just the old spirits come out of the woods.”

'We are here today'

Over a 25-year period ending in 1931, the Algonquins at Wolf Lake saw their population decimated, according to a letter from the area’s Indian Agent to the secretary of the Indian Affairs Department.

“About 25 years ago, there were 330 Indians; now there are 41 including half-breeds, 31 Indians in all,” said the Aug. 3, 1931, letter.

The letter said that Wolf Lake's chief, identified only as Petremont, his wife and nine of his 10 children had died.

“The Indians are dying so fast that it is not worth making a new chief,” said the letter.

“There are among these Indians only four or five men who are strong and able to work. Kindly advise me if anything is to be done to these Indians.”

The people of Wolf Lake now number 242, and current Wolf Lake Chief Lisa Robinson said this past, though painful, gives her community strength and hope — their survival is a result of their resilience.

“For our people, there have been waves of epidemics that have happened: the whooping cough, influenza, smallpox, Spanish flu, measles, tuberculosis, and there were others as well,” said Robinson.

“It was with that resilience and their effort and strength to carry forward, to continue to rebuild, to regroup, to come together again, that we are here today and we will continue to be here.”

'Pretty near all die'

There was another Algonquin village with 10 families on the east arm of Grand Lac Dumoins, roughly 50 kilometres east of Témiscaming, called The-Mouth-of-the-Moose that was nearly wiped out by the Spanish flu. Only the mixed-blood family in the village survived along with five adults and three children from the other families, according to Moore’s book.

“That time, the people pretty near all die, that time. Not too many left, just us,” said the late Paddy Reynolds, in a transcript of an interview conducted by Moore.

Reynolds was a child when the pandemic hit, and his father ran a trading post there. He said all the houses in the village, which were made of square timber, were later torn down by trappers looking for firewood.

'Our people regrouped'

Robinson, the Wolf Lake chief, remembers a story she was told once about the Spanish flu pandemic that was ravaging her people at one of their settlements.

“There were a number of families dying over the course of the winter,” she said.

There was one family where the mother refused to let her children out, even after it seemed the pandemic had waned, said Robinson. Other people did venture outside, even those who had recovered from the Spanish flu, but they were all soon felled by another bout of sickness that killed more people, she said.

“And this woman kept her children in and they survived that second round,” said Robinson.

Robinson remembered that story recently as public health orders for physical distancing swept across the country in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Robinson said it shows that her people on their own, nearly a century ago, realized that physical distancing was key to survival.

“In instances where there was a lot of suffering and there was loss of lives, our people regrouped and came back, and so to me the strongest message is the resiliency of our people to continue to move forward.”

For her, this history, which shaped and moulded her people, echoes through all their actions today in the face of COVID-19, strengthening their link to the old ways and traditions.

She said people are recalling not only the past stories of disease, but also the traditional medicines they turned to during those times.

“That is so important to maintain that connection and that knowledge ... that is another positive aspect I see."

The First Nation is still working to establish reserve lands in its ancestral territory.