January 3, 2020

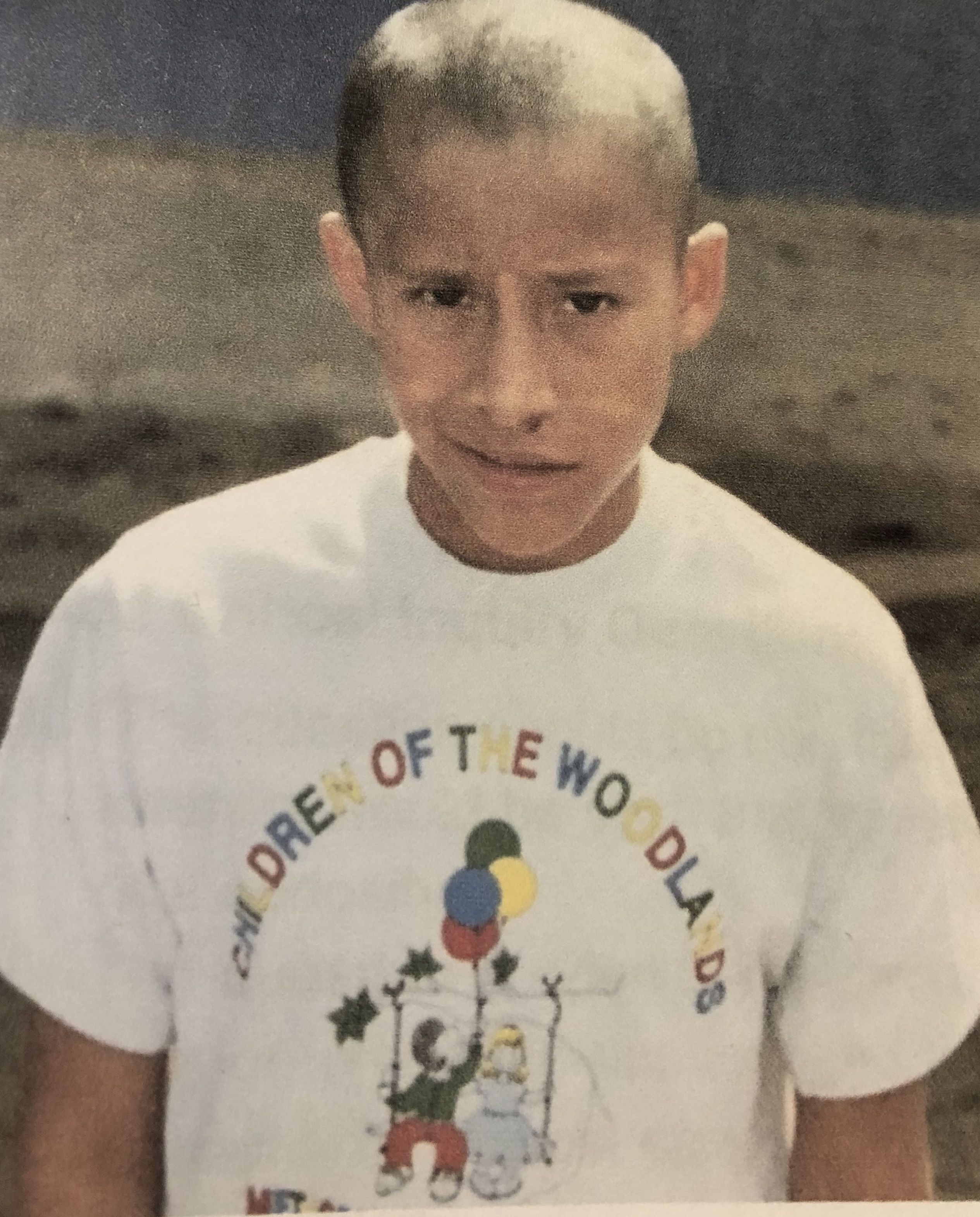

When Leceta Chisholm Guibault looks at childhood photos of her son Alexander, tears fall from her eyes.

"I know how much Alex loves his hair and when I see it shaved like that and I see blood on his nose and a little crooked smile, it breaks my heart right there. Because that's my little boy in an orphanage," she says at their cottage home on Lake Mush-a-Mush along Nova Scotia's southern shore.

Alexander Chisholm Guibault's life today seems like a dream, but it's haunted by a nightmare.

He lives with his mother in a pretty cottage on a pristine lake. He spends his days working on a book about his life, or travelling across North America to give talks. The talks are part catharsis, part advocacy. He's trying to figure out exactly what happened to him, and how he can stop it from happening to others.

He's 27 years old, but in some ways he feels like he was reborn seven years ago. He was 19 when he met the Nova Scotian woman who would become his mother.

He'd spent much of the past decade living in a Guatemalan orphanage that looked and operated more like a prison. The orphanage, he says, kept the kids inside its high walls, alternately making them spend days picking grass out of the concrete flags covering the ground, or ignoring them.

A police officer brought Alex to the orphanage when the boy was about nine. The officer didn't know his name, so he called him Jesus.

Jesus had by then survived a year or two on the streets, eating from trash cans and sleeping in the shadows. He was always hungry. He hung out with other street kids, prostitutes and gang members.

The boy found a better name in a book an orphanage friend gave him. It was about Alexander the Great, the ancient king and military leader.

"I put the two books in front of him. And I said this is the Bible and this is the book of Alexander the Great. I thought, seriously, I am not a Jesus. I don't look like a Jesus, I don't want to be a Jesus. I am Alexander. Maybe not the great part, I thought, but I do want to be Alexander," he says with a laugh.

"I liked that he was very positive. I liked that he was a fighter. I liked that he was a king and he never gave up. And for me, he became a little bit of a symbol."

He needed the strength. His parents had forced him to do manual labour in fields until he was seven, he says, when they sold him to a stranger for $2,000.

His first recollection comes from when he was about that age. His memory was bolstered a few years ago, when he and Leceta tracked down his biological family. The pair have spent much of the last eight years searching for hard evidence of what he remembers about his early years.

His brothers and sisters confirmed that his parents had sold him to an organ harvester who locked him in a basement.

"The first memory that I had was somebody kicking me on the stomach. I got up quickly and started to look around. I didn't know what was happening. I started to look around and there was 11 other kids," he says.

"I noticed there was a rope tied to a wooden post. The post was in the middle and there was a rope on my left leg."

He remembers an adult numbering the children; Alex was Number 6. He learned the adults planned to kill them and sell their organs on the black market.

A 2016 report by the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala found more than 48,000 people were victims of illegal human trafficking in that country. Many were children sold by their families, mostly to be sexually exploited. It's not clear how many were sold for organ harvesting.

Alex managed to escape to the streets of Guatemala City. "There were a lot of gangs, prostitution. I spent at least a year of starving, doing inhalants. I witnessed a lot of violence," he says.

At the American-run orphanage, life got worse, he says. "One of the things I always wanted was to belong, or to be part of a family. I prayed to God, I begged. I kind of believed in magic and I thought that could be a way to get a family. I cried a lot."

The orphanage director told him he was too ugly, too stupid, to be adopted. He did have one friend, an American sponsor named Tony. Tony sent him money. Alex sent him thank-you cards. The photo of Alex with blood on his nose and a crooked smile was taken to be included in a thank-you card one Christmas.

"When I showed him the picture, Alex told me he remembered that day because his dorm parents had held him down and they beat him," Leceta says.

"And they'd shaved his head. And then they made him stand up. They told him they were going to take his picture and it was for his sponsor. And they told him he better look grateful. He'd better smile and look grateful."

He smiled and tried to look grateful. In his young mind, if someone fed and sheltered him, they could do to him whatever else they wanted.

In 2011, the orphanage director kicked him out, he says. He was 18 and likely too old to be adopted. Alexander returned to the streets. He didn't have many things going for him, but he did speak fluent English as a result of talking to the American staff at the orphanage and reading the Bible in English.

"Education was always important for me. I was told it can open a lot of doors in your life," he says. "It is sad right now and it hurts me to put it that way, but when I was kicked out, I thought if I go to school, if I can graduate, if I can get my diploma and present it to this director, he might be proud of me. He might shake my hand and say, 'Good job, Alex.'"

In Guatemala, after Grade 6, students have to pay their own way. Alexander says he walked the city blocks, eyes on the ground, collecting loose change for tuition and food. He had three pairs of pants, three pairs of underwear and three shirts. He kept clean by showering in public water fountains. He did his homework in the parks that kept the light on until 2 a.m. He was always hungry.

He graduated and brought the orphanage director a ticket to the ceremony. "He ripped it up and threw it at me. He said I was not worth it," Alexander says. "It hurt me a lot. I wanted to make someone proud of me. I knew he might never see me as a son, but I always saw him as a father."

Seven times, he says, he tried to end his life. The week after the seventh attempt, he got a job translating for a visiting group of Canadians. It was April 2012. He spent a lot of time with the group, who were there to volunteer in orphanages. At the end of the week, he asked if he could tell them his story.

One of the Canadians was Leceta Chisholm Guilbault. Leceta had been volunteering at Guatemalan orphanages since 2000. She and her husband, Jean, had adopted two infant children in the 1990s, Tristan from Colombia and Kahleah from Guatemala. Their kids were grown now.

Leceta had heard many hard stories and met a lot of lost children.

But she saw something new in Alexander's haunted eyes as he gave his testimonial. "He had some of the darkest, almost scariest eyes, most troubling eyes, I'd ever seen," she says.

"My mom was the first person who started to cry for me," he remembers. "I remember at the very end, after the 20 minutes I talked, she came and hugged me. And I felt that hug and I thought, this is the way that a mom will cry, will hug you, if something happened to a kid."

Leceta returned to Canada. She spoke to her family. Somehow, an unexpected truth emerged: Leceta knew Alex was her son, and he knew she was his mother.

"Alex is 100 percent my son. Sometimes I forget that I missed the first 19 years of his life. I often grieve those first 19 years, because even though I wasn't there when he was being hurt and suffering, my heart reacts to it as if I should have been," she says.

Her husband and two children agreed. In 2014, they started the complicated process of international adoption. Guatemala finally approved the adoption in 2016, recognizing Alex as the legal son of Leceta and Jean. He took on their last names and officially changed his own name from Jesus to Alexander.

Alex visited Canada first in 2015. He was shocked by the weather and surprised by the people.

"It was a bit cold and I was like, this is another world! Everybody's nice to me here. Everybody's gentle here. We did have a house in the city in Nova Scotia. It was the first, I would say, the first place that I kind of felt like it was a home," he says.

He's trying to follow the adoption process to becoming a Canadian citizen. "Alex has waited his whole life for family and the one gift I would like to be able to give him as his mother is citizenship," Leceta says. "My citizenship."

Until then, he can't work here or study. He dreams of going to university in Canada. He says he could study for the rest of his life and not learn enough.

Alexander is also figuring out at what he wants to be great. It might be writing. He's spent the last few years pouring out his story into a book he's calling Looking at My Past, I Found My Future.

He's also travelled Canada and the U.S. to give talks to thousands of people. He tells them his story and urges them to support his ongoing volunteer work in Guatemala.

He and Leceta regularly return to his birth country to donate beds to those living in deep poverty, to buy food for the hungry, and to fund scholarships to young people wanting to further their education.

Alex is Indigenous and found an unexpected bond with Mi'kmaw students in the Maritimes. "When we walked into the school, right away students recognized Alex as a cousin. They came, they hugged him, they welcomed him into the school," his mother says.

As survivors and children of those who survived residential schools, many Indigenous people in Canada understand Alex's life in a way others cannot.

Mother and son regularly return to Guatemala with Our Guatemala: Travel With Purpose, a group they run to offer guided tours of Alex's Guatemala to those who want to help. They also bring beds, give food and fund scholarships to help kids on the edge.

"I know the need. I see the need. I grew up with the need," Alex says. "And it makes me feel happy if I go back and try to help them. Obviously changing the world is a big responsibility. But if we do it one step at a time, eventually, we'll get there."

Leceta looks at Alex today and smiles. "He's happy and he's healthy. His hair is gorgeous and he has purpose and he has a family and he has opportunities. He's healing. He's healing beautifully. So they're like they're the same person, but they're two different people," she says. "That's what I see. My son."