November 17, 2020

The boys thought they were being quite brave that summer evening as they walked down the back alley toward the Cook house.

After setting pins at the local bowling alley in Stettler, Alta., they spent their earnings on chips and pop, then decided to stroll past the little white house on 52nd Street.

Days earlier, on June 28, 1959, the bodies of seven family members had been discovered in a grease pit in the garage on the property.

Robert Raymond Cook, 22, was arrested in the killing of his father Raymond Cook, 51, stepmother Daisy Cook, 37, and his five half-siblings.

The parents had been shot, and the five children, aged three to nine, beaten.

On their way to the crime scene that night, Malcolm Fischer, 9, and his cousin stole some peas and carrots from a neighbouring garden.

When a police officer jumped out of the thick caragana bushes behind the Cook house, Fischer said he thought he was going to be shot over pilfered vegetables.

Instead, the officer told the boys it was dangerous to be out, and walked them back to Fischer’s aunt and uncle’s house.

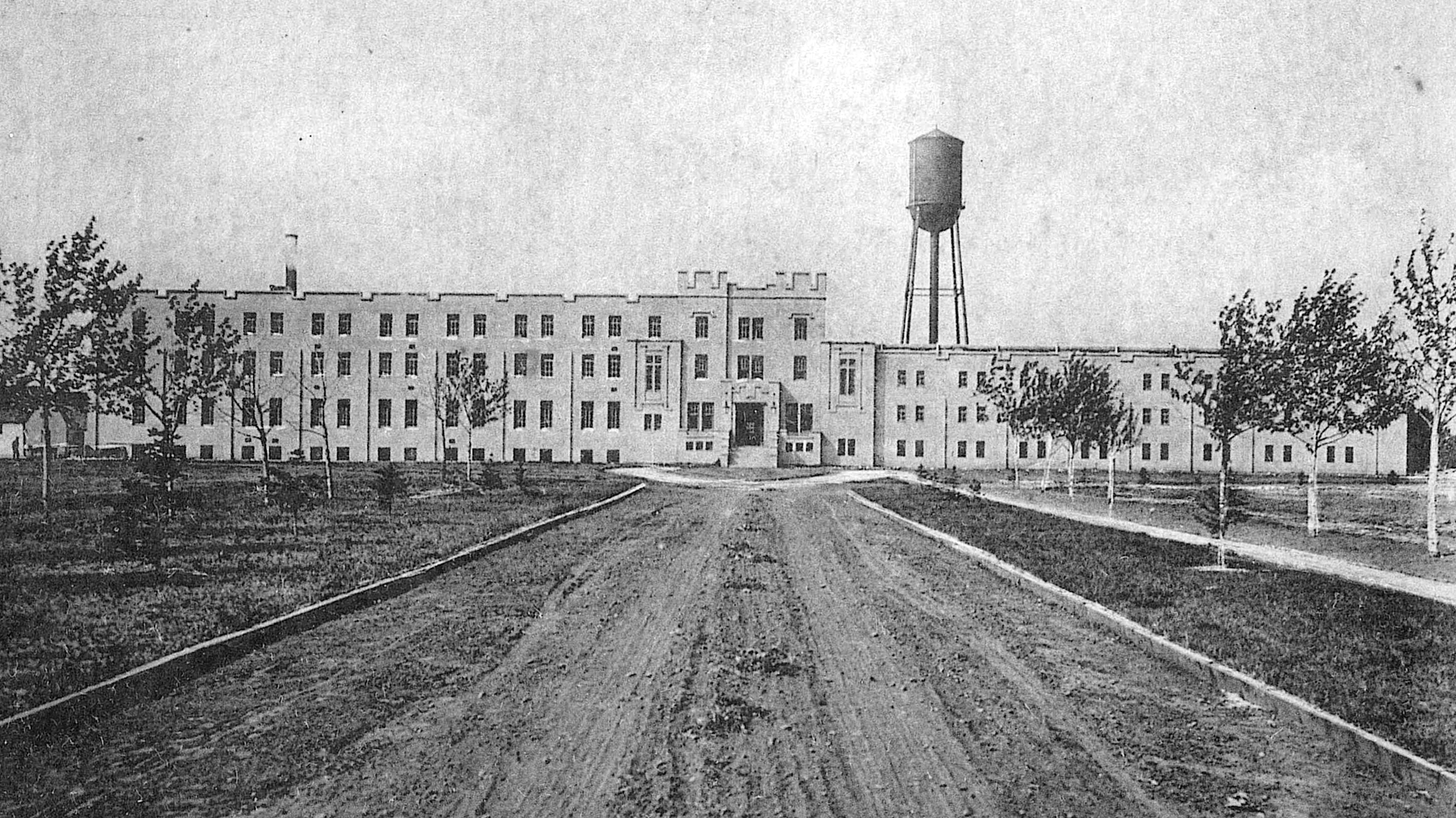

There, they saw Cook’s face flash on the TV as broadcasters warned the suspected killer had escaped from the mental health hospital at Ponoka, Alta., about 90 kilometres to the northwest, where he was being held for assessment.

He stole a car and led police on a chase. He rolled the vehicle, but then got away on foot.

“The whole area, including much of Alberta, went into hysteria. It wouldn’t be overstating it at all,” Fischer, a retired educator and current Stettler town councillor, said in a recent interview.

Newspapers at the time heralded the search for Cook as the largest manhunt in Alberta history, as more than 100 RCMP officers and 60 Canadian Army troops scoured the area.

As word of the escape spread during those hot, mid-July days, farmers and townspeople across central Alberta armed themselves and kept overnight vigils.

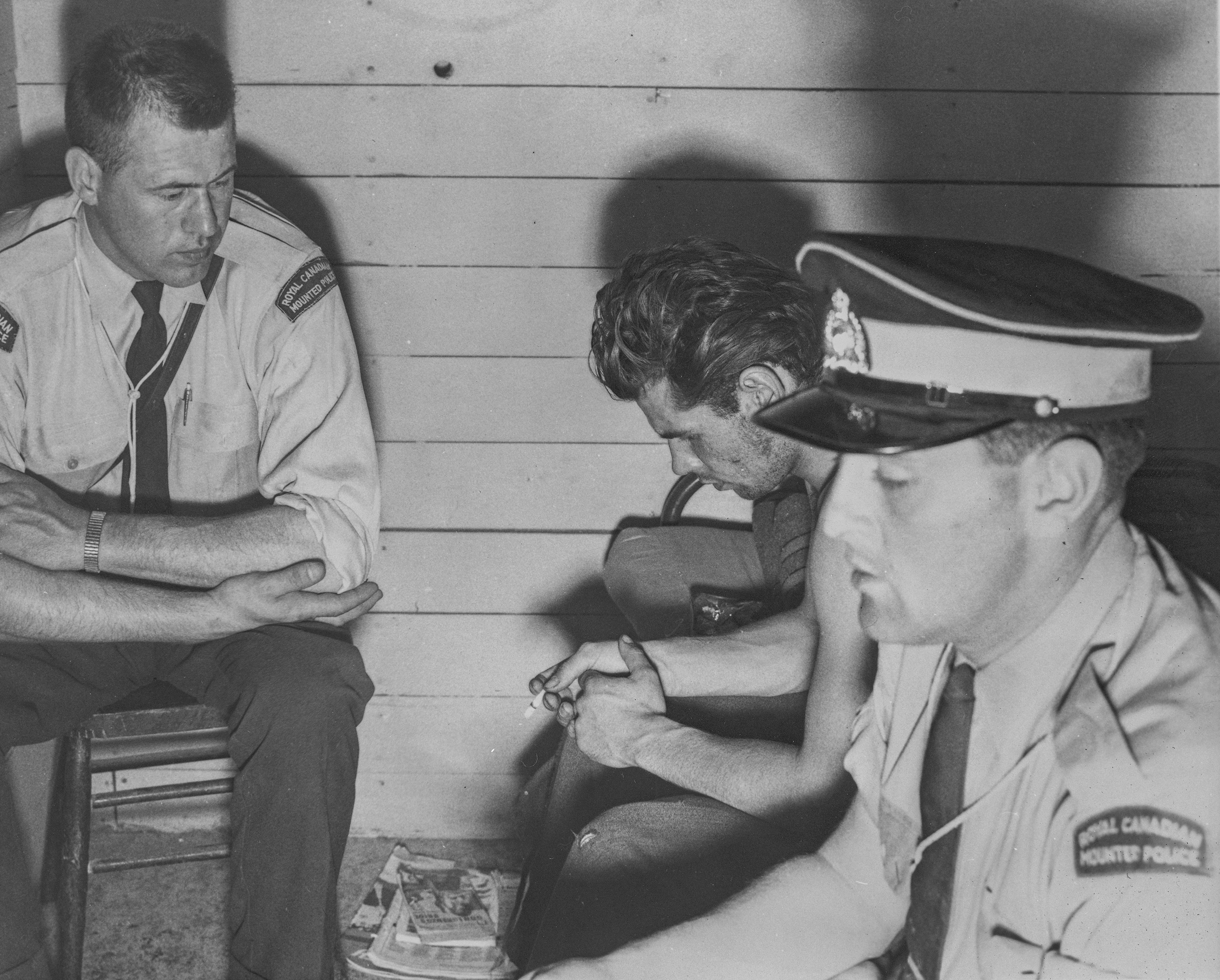

Cook was captured a few days later, on a farm near Bashaw, Alta. Weak and unarmed, he was wearing the pyjamas he had on when he broke out of the hospital.

“I didn’t do this ... I couldn’t have done it.” — Robert Raymond Cook

Cook only stood trial for his father’s death. On the witness stand in December 1959, he addressed the packed courtroom in a low, halting voice, according to a report by The Canadian Press.

“If you found out your family was all killed and you’d been charged with murder ... it’s hard to understand,” he said. “The only thing I knew about the whole thing was that I didn’t do it.”

The jury found him guilty on Dec. 10, 1959.

Given an opportunity to speak before being sentenced, Cook again professed his innocence, according to a report that ran in the Calgary Herald the next day.

“I didn’t do this ... I couldn’t have done it,” Cook said.

The trial judge sentenced him to hang.

Cook appealed, but was found guilty again following a second trial.

When a plea for his sentence to be commuted was rejected by federal officials, he was hanged on Nov. 15, 1960, the last person to die by capital punishment in Alberta before it was formally abolished in Canada in 1976.

Six decades later, the intrigue and debate about the case live on in Stettler and surrounding communities.

The most prominent among the skeptics is David MacNaughton, one of Cook’s defence lawyers.

Now a retired provincial court judge, MacNaughton, 92, maintains there was enough reasonable doubt that the outcome for his client ought to have been different.

“It’s not a case of I’m sure he’s innocent,” MacNaughton said. “It’s that I’m not sure he’s guilty.”

Fischer, who remained fascinated with the case as he grew up, believes there’s more than enough evidence, albeit circumstantial, to show Cook was guilty.

For years, Fischer and MacNaughton have been teaming up to present their opposing views to Grade 8 students in Stettler, 80 kilometres east of Red Deer.

In 2019, the town’s public library asked them to give the talk to a wider audience, and more than 300 people showed up. The library filmed the event, and has since sold about 100 copies of it on DVD.

Fischer said he assumed interest would die out, but it hasn’t. He chalks that up to the combined notoriety of Cook being Alberta’s last hanged man along with facts of the case itself.

“You had horrible murder, you had an escape from a mental hospital, you had a car chase — why it’s not in Hollywood, I do not know,” he said.

Each man can point to particulars and bits of evidence from the well-documented case to support his own view.

But there are also the urban legends that still surface around tables in Stettler coffee shops, as well the impressions and theories of people who knew the Cooks or others involved in the case.

“We love conspiracies, don’t we?” said Fischer. “Based on the evidence, what’s the most likely scenario?... I’m sure there’s at least 50 different versions of what probably happened.”

Fischer said many people’s impressions of the good-looking and charming Cook were that he couldn’t have done it.

“Now those aren’t the people who knew him really well. The people who knew him really well, that’s a different story,” he said.

MacNaugton concedes Cook had a criminal past and was a good liar, but he also had an alibi — that he was participating in a robbery in Edmonton that night — and the retired judge thinks there were just too many outstanding questions left unanswered.

“He never ever admitted to me or to anybody else that he’d done this, and ... I don’t know. And that’s why the people still argue about this.”

MacNaughton was only two years into his career as a lawyer when he worked with more experienced counsel on Cook’s case. It was the only capital punishment case he ever worked on.

“I’ve always been against capital punishment because it’s so final,” he said. “If there’s an error made, an apology doesn’t do much good.”

Between 1867 and 1962, 710 people were executed in Canada, and 400 death sentences were commuted.

The death penalty was officially abolished in 1976. There were regular federal motions seeking to abolish the death penalty begininning in the 1950s, but none passed in time to save Cook.

He was executed at a jail in Fort Saskatchewan, Alta., the last of 29 people who were put to death there between 1916 and 1960, according to Kyle Bjornson, curator of the Fort Heritage Precinct in the city.

He said Cook left his eyes to the Edmonton eye bank, and donated his body to the University of Alberta Hospital for medical research.

The jail itself was long ago demolished, but now and then visitors to the city’s Fort Heritage Precinct will ask staff about Cook.

A few years ago, the museum acquired a piece of the noose that was reportedly used to hang him.

The donor said a relative, a custodian at the old jail, had taken the rope and held onto it for years.

“It is kind of a dark chapter in our history, capital punishment, and it can feel a little macabre, but I think it’s important in telling that history that this was a jail town and a hanging jail town,” Bjornson said.

Over the years, the story of the Cook family killings and the last man hanged in Alberta has been told and retold, well beyond classrooms and libraries in Stettler.

It has been featured in newspapers and books, a documentary and even a play.

MacNaughton’s daughter, retired Red Deer lawyer Pamela MacNaughton, is herself in the process of going through thousands of pages of transcripts from the trials.

She hopes to produce a podcast series to explore what she has learned, including testimony from the medical examiner and other witnesses that changed over time, the lack of forensic evidence and problems with the timeline proposed by the prosecution.

“I quite frankly don’t see how he could have done it,” she said. “I don’t think there’s been a real in-depth investigation of this, so I’m going to give it a go.”

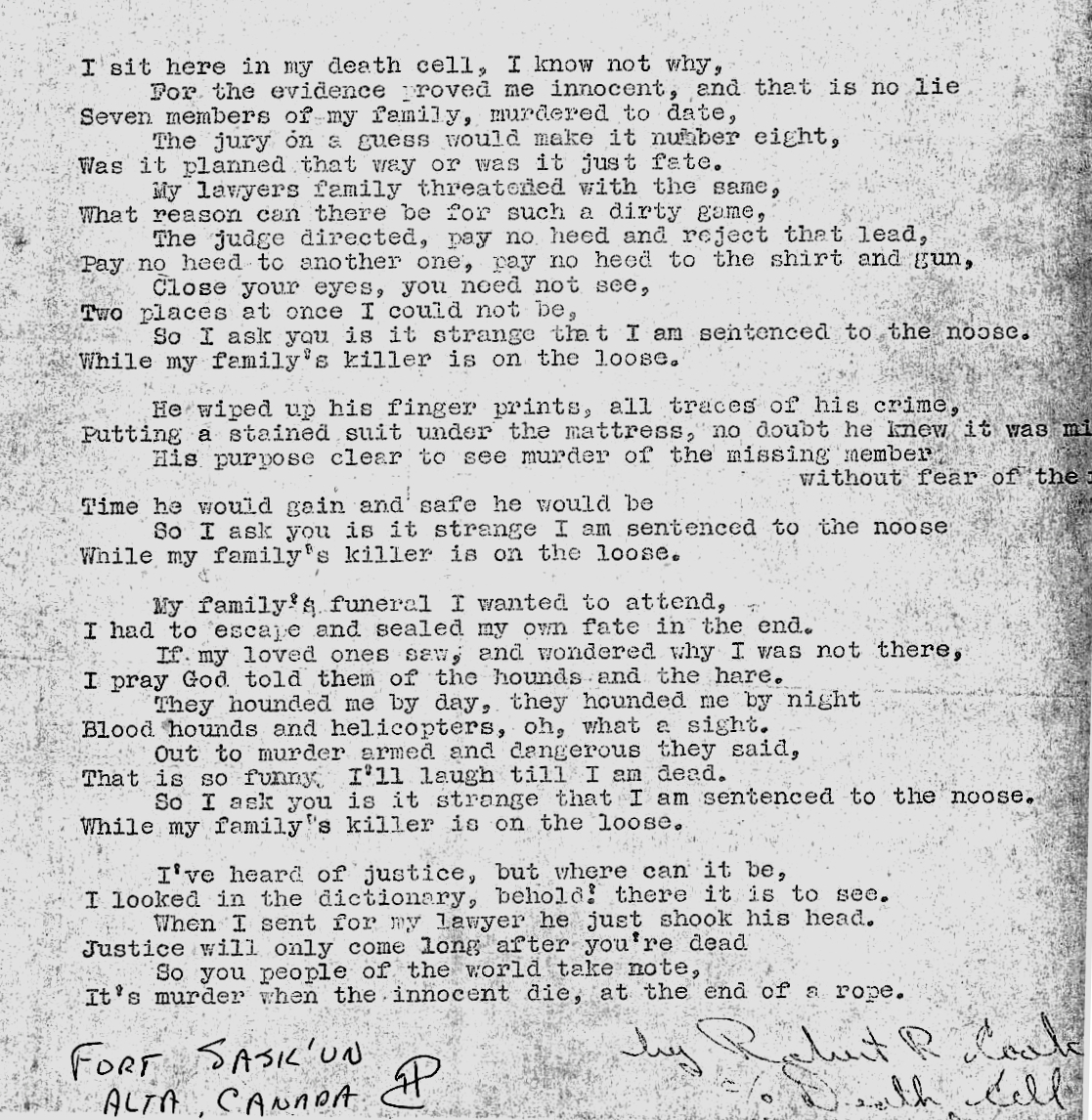

If she does turn something up, it could fulfil a prediction Cook himself made in the final stanza of a poem found in his cell after he was executed, in which he professed his innocence.

When I sent for my lawyer he just shook his head

Justice will only come long after you’re dead.

So you people of the world take note,

It’s murder when the innocent die at the end of a rope.