September 5, 2020

Paula Simons was eating breakfast in her parents' kitchen when her father angrily waved the latest issue of the Edmonton Journal in front of her.

It was January 1988. News broke in the Journal that Maurice Sychuk, a University of Alberta law professor, had been arrested and charged with second-degree murder in the death of his wife, Claudia.

Simons's father — a trained opera singer who "expressed his anger and outrage fortissimo" — was a lawyer himself, and knew Sychuk's temper by reputation.

"Everyone knew something like this would happen one day," he grumbled.

At 23, Simons had recently landed her first journalism job at a controversial conservative weekly newsmagazine called the Alberta Report.

Simons hadn't intended to apply at the Report — which she tended to refer to privately as "that fascist rag" — but as a recent journalism graduate during a major economic downturn in Alberta, Simons interviewed for and eventually secured a position as a part-time weekend copy editor.

On that chilly January weekend, Simons finished her breakfast and headed to the Report newsroom, located in a one-storey building with lots of windows in an industrial park northwest of West Edmonton Mall.

It was the weekend after New Year's Eve, so the large, open newsroom was mostly vacant, save the rows of Commodore 64 computers, the fax machine (cherished by staffers with what Simons remembers as “holy reverence”) and an executive editor, sitting at his desk in the far right corner at the back of the room.

The magazine was a weekly, and Simons's role was to edit that week's copy. But with the Sychuk story breaking and no reporters available, Simons was quickly assigned to cover it — her first for the magazine.

The details came quickly enough. Sychuk and Claudia had been out for a New Year's Eve dinner at the Edmonton Petroleum Club. They'd come home, become involved in a domestic dispute. She was stabbed with a hunting knife.

You need to find a photo for this story, Simons was told. But as far as she could tell, Claudia had no family in Edmonton.

Well, her editor said, phone the funeral home. Ask if the Report can get a picture of Claudia in her coffin.

"I can't do that!" Simons exclaimed.

"Do you want to be a reporter?" her editor asked.

So Simons called and was met with a hostile reaction from the funeral home, where someone hung up on her. But the point was taken — go get the news.

Instead, Simons called the Edmonton Petroleum Club and the details she learned formed the lede of her first story — the Sychuks had beef Wellington and baked Alaska, served by waiters wearing white gloves, and then Sychuk went home and killed his wife. (He was later convicted of second-degree murder.)

Such an attitude towards newsgathering was emblematic of the Report’s personality: brash, confrontational, mischievous. The magazine demanded the attention of its audience, some of whom happened to be among the most powerful in the province.

For many in Western Canada, the Report needs no introduction. A passing mention of the name among those familiar is likely to provoke any number of reactions — a scoff, a wistful comment, an exasperated sigh.

But for those who came to Alberta after the magazine folded in 2003 and its obvious influence faded, some of the columns and editorials from its alumni can be jolting when they resurface years later.

That was the case for Premier Jason Kenney's speechwriter Paul Bunner, who penned a number of columns modern critics called racist and discriminatory, or Alberta social studies curriculum adviser Chris Champion, who in the pages of the Report suggested victims of school sex abuse scandals and forced sterilization were seeking profit from their past.

In the past number of months, old articles from both men resurfaced in news reports and on social media and prompted calls for their resignations. Bunner is set to retire this weekend.

"It made me feel very old when I saw people digging up [Alberta Report] columns and being shocked by them," said Simons, who is now an Independent senator for Alberta, following decades of work as a journalist and columnist for CBC News and the Edmonton Journal. "I thought there were no secrets to what Alberta Report's views were.

"But at its height … it really did do a tremendous amount to crystallize Alberta's cultural identity."

Some may feel it justified to dismiss the Report as a relic of a different time, a magazine that occasionally played host to social rhetoric — especially surrounding LGBTQ issues — that mainstream society might deem hateful today.

But the cyclical nature of many of the issues it focused on — and the familiar refrains of alienation in the West that are still trumpeted at the highest levels of the provincial government — mean the Report of the 1980s can teach us much about the Alberta of the 2020s.

And there's no understanding the Alberta Report without understanding its founder, Ted Byfield, a man who is described by those who knew him as being many things at once: egotistical, manipulative, irritable and an occasional bully, but also ambitious, charming, warm-hearted and extremely clever.

"Any future historian trying to understand Canada's troubles in the late 20th century will want to look at Mr. Byfield's work," author and political commentator David Frum wrote in the preface to Byfield's 1998 collection of back page essays, The Book of Ted.

"Unless you've read Mr. Byfield, you won't ever properly understand the anger of the West at Central Canada, the reasons for the destruction of the once-unbreakable Conservative grip on the West, and the birth of the Reform Party."

St. John's Edmonton Report

The Alberta Report began its life in 1973 as the St. John's Edmonton Report, a publication produced by the Company of the Cross, an Anglican lay order founded by Byfield and Frank Wiens that ran three boys boarding schools.

Early members of the press group, who were not members of the boarding school, remember how they were provided with pay of $1 a day, plus free lodging, enough food for three meals a day and an extra dollar to buy tobacco.

Byfield himself was an adult convert to traditional Anglicanism and was particularly influenced by the work of Christian apologist C. S. Lewis. The magazine, in his conception, functioned to serve two roles: as a traditional newsmagazine, but also, through its opinion columns, as a tool to draw readers to the Christian faith.

Brian Bergman was an English student at the University of Alberta in 1978, looking for work. While not planning on working in journalism, he ended up meeting one of Byfield's daughters, who covered education for the Report and pitched him on the magazine.

"She said, 'Well, you know, it's a funny thing — my father is starting to hire reporters for the first time,' " Bergman said. "And I thought, 'Well, that's kind of an odd way to put it.' "

Oblivious to the content published by the Report, Bergman became its first paid employee. For Bergman, walking into the Report offices was like walking into something from another time.

"You walked up these rickety steps to the newsroom where the editors were all kind of in a small circle facing Ted," said Bergman, who went on to write for Maclean's and the Edmonton Journal.

"The reporters were huddled with desks in an outer circle. And it was just … it was a crazy place."

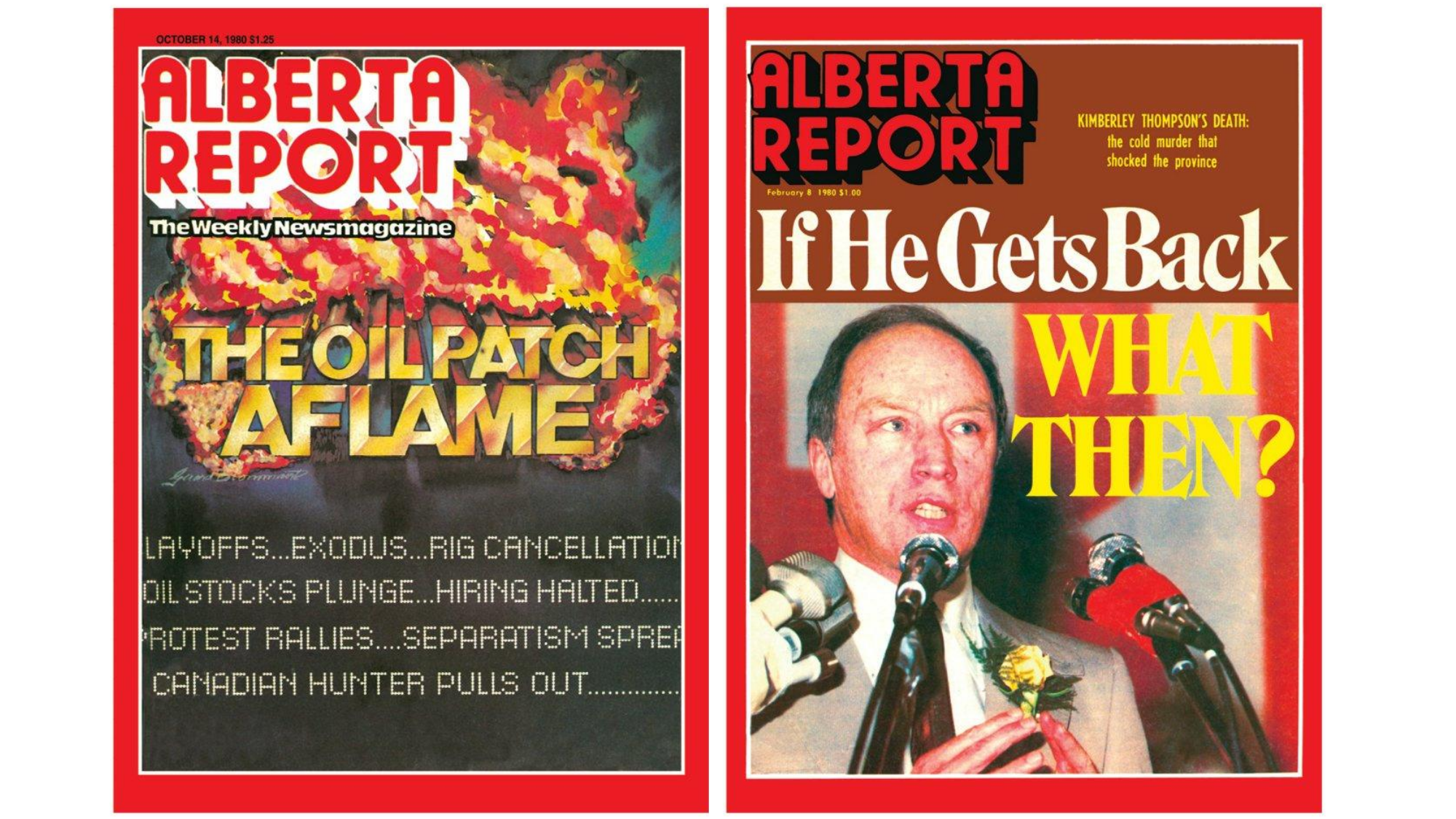

The Report in those years took its cues from Time magazine — emulating on a philosophical level the fervent anti-communist credo of co-founder Henry Luce, and on a tangible level adopting the distinct red border that surrounded the cover of each issue of the U.S. publication.

For that, Time sent a letter to Byfield, arguing that he had breached trademark law.

"We're terribly gratified," Byfield told Maclean's in 1983, "that [Time] would look down from New York and consider us a problem."

Byfield refused to change the design, and further provoked the larger company with deeper pockets by tipping off other local media about the possible lawsuit. Eventually, as a story about the lawsuit was featured in the pages of Maclean’s, Time dropped the case.

Byfield would go into the Report offices on Sundays after church to peruse all of the daily papers available in Western Canada. From noon until midnight, he would paw through the Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star and various Prairie print papers, flagging stories he felt were poorly covered.

Much like Time, the weekly Report didn't bother chasing the immediate details of a story. In a hypothetical situation, were a plane were to crash, the Report would let the dailies report out the facts of the crash, then follow up with the "real story" — for example, the passenger at the scene who tried to save the lives of four people.

"The reporters got good at seeing the story behind the story. Which is really the technique of journalism when it's well done," Byfield, who is now 92, said in an interview with CBC News. "The people who went through that process became some of the leaders in journalism today."

Plucked from a different era

Byfield — with a well-lined face and big bushy eyebrows — resembled actors Walter Matthau and Humphrey Bogart and 60 Minutes newsman Mike Wallace. He usually wore a suit, although he says he never felt like "a suit."

The way that some former writers tell it, it was as if he had been plucked out of an era depicted in films like His Girl Friday (1940), when reporters drank hard, wore fedora hats and smoked in the newsroom.

The ramshackle Report office saw editors working at desks pushed together to resemble a table for six, firing away on typewriters loaded with eight-by-11-inch paper. When stories were completed, editors would staple them together and place them in a basket.

"And Ted would come whirling in from a meeting and the copy would pile up," said former Maclean's senior writer D'Arcy Jenish, the Report's first Ottawa bureau chief. "He'd sit at the head of the table and start fishing out the stories in the copy basket.

"And he'd get to yours, and you'd be on pins and needles hoping you got things right. Because if you didn't, the whole newsroom would hear about it."

When Byfield got mad, he reminded some writers of the character of Howard Beale, the "angry man" news anchor in the 1976 film Network, who urged his audience to yell, "I'm as mad as hell, and I'm not going to take this anymore!" Byfield's explosive temper led him to rip telephones from walls and hurl coffee cups across the room. Once, he even broke his hand at home after punching a TV screen that he couldn't get to function. He was in a cast for days.

As one former writer put it, working at the Report was educational — in the same way being in the marines is educational.

Byfield worked side by side in the office with his wife, Virginia, with whom he frequently clashed in shouting matches. But he trusted and loved her deeply, and sought her advice on most everything he wrote.

Virginia shared Byfield's reputation for being extremely demanding with Report staffers — but had her methods when it came to defusing her temperamental husband.

"[Losing her] was by far the hardest blow I've ever had to sustain," Byfield said of his wife, who died in 2014.

"She was funny as hell. [One time], I was whining and [complaining] about something. She finally looked at me and she said, 'You know, I'd like to say that I shared in your sadness over this, but the trouble is that neither I, nor anybody I know, could think of any form of sympathy to extend to you that you're not already extending to yourself.'"

Hobby horses

For the writers who worked for him, it was clear which causes Byfield personally felt attached to. Byfield's faith provided the basis for many of his moral positions, and he used the pages of the Report's editorial sections to champion his points of view, scorning political correctness and "thought police."

"Most of the stories, the editor would usually go over it pretty heavily, but depending on the story, whether it had one of Byfield's hobby horses [would sometimes determine] if it would get a Byfield gloss or not," said former Report writer Shawn McCarthy.

"He didn't like the teachers union, so he was always editorializing against the teachers union. He didn't like the human rights commission, which he felt was a government imposition against the conservative mores of the time."

McCarthy was among those Report staffers who didn't share the editorial views of the magazine. Before joining the Report, he went for dinner with Byfield and members of the magazine's Calgary bureau.

On every topic raised, McCarthy soon found himself in heated argument with Byfield. Toward the end of the night, excusing himself into the washroom, McCarthy paused and reflected at a urinal: "Well, guess I blew this interview."

Soon, Byfield entered the washroom and pulled up to the adjacent urinal. Gruffly, he inquired: "So, when do you start, McCarthy?"

"That was the kind of guy he was," said McCarthy, who went on to write for the Globe and Mail, Toronto Star and The Canadian Press. "He liked to have people around him he disagreed with. So it wasn't a place where everybody was a true believer."

Byfield had a mischievous streak, too, dating back to his days on the city hall beat at the Winnipeg Free Press. He would frequently retell an incident involving a scandal involving civic funds.

Council had not been exactly forthcoming about the details of that scandal and had taken to meeting behind closed doors without the media

So Byfield somehow squirmed into a duct in the ceiling and manoeuvred his way into a position perfect for eavesdropping on the private meeting.

Simons remembered him regaling his audience with the story while at a big journalism conference at the Banff Centre.

"A lot of young journalists in the room, the progressive reporters from the Edmonton Journal, they were horrified that [Byfield] was asked to be a guest speaker," Simons said.

"But he told this story with such a wicked twinkle in his eye, by the time he was done, he had convinced them that trespass was a perfectly legitimate journalism tool."

'At the edge of the volcano'

In 1979, as the magazine morphed from the St. John's Edmonton Report into the Alberta Report, Byfield found himself a new foe. A situation began to emerge in Alberta in 1980 that sounds a lot like the Alberta of 2020.

The prime minister was Pierre Trudeau, the oil industry in Alberta was going through a tumultuous period, and prominent conservatives in the province were flirting with the concept of separation, whether as a legitimate threat or an advantageous bluff.

In 1980, Trudeau introduced the National Energy Program, an initiative the federal government said would make Canada self-sufficient as an oil producer by 1990. But critics in the West saw the program as the Trudeau government encroaching into provincial affairs — and it was in that context that Byfield took to the pages of the Report in a hot fury.

In Byfield's view, the implementation of the NEP signalled that Trudeau was no longer simply "indifferent" to Western Canada — that, for a multitude of reasons, he now "hated" Western Canada.

"It is the hatred of the socialist for the individualist, the cold fear of the high-born for the self-made, the aversion of the theorist for the pragmatist, the derision of the urbanist for the peasant, the disdain of the intellectual for the uncouth, the contempt of the Gaul for the Slav," Byfield wrote on Nov. 7, 1980.

"All these hatreds have helped to dictate the posture of the Trudeau government towards the West, and on Tuesday, the 28th of October [the day the NEP was introduced], they were paraded before the nation in the form of public policy."

Having joined the magazine a year prior — just as Joe Clark's short-lived federal Progressive Conservative government fell — Jenish said the arrival of the NEP landed like a bomb in Alberta, and being at the Report gave him a "seat at the edge of the volcano."

"[Byfield's] rage incited and maybe inflamed public opinion a little bit. It responded to a visceral feeling amongst Albertans that they were really getting screwed over by the government," Jenish said.

"Ted kind of articulated what people were feeling viscerally, but weren't exactly capable of expressing."

As the content covered continued to diversify — with politically charged articles but also stories of fires, medical breakthroughs, lawsuits, sports and art — so did its circulation. At its height, the Report had a subscription base of nearly 60,000, according to the Provincial Archives of Alberta.

'The West Wants In'

Byfield's writing — described by Jenish as forceful and articulate, and "totally in sync with the public mood of the moment" — soon raised eyebrows within the provincial government.

Byfield's connections with those in power grew, and staffers began to notice his increasingly frequent meetings with individuals like longtime Alberta Premier Peter Lougheed and eventual Reform Party founder Preston Manning.

"In the early '80s, oil prices took a nosedive. You had a combination of the NEP and a drop in oil prices, and it just led to this terrible recession in Alberta," Jenish said. "All the dire warnings and forecasts that Ted was warning, in fact, came true. So it gave him a lot of credibility."

The magazine became a home for resentment and grievances against Confederation, arguing that Western provinces had been unfairly treated and should have more power over national economic policies.

Though Byfield wasn't an advocate for separatism — threatening separation when things don't go your way is "no way to run a country," he said — the Report frequently covered those who advocated for such things as a way to draw attention to larger Western grievances.

"People in the East started picking up on it. I mean, Ted was constantly being interviewed as kind of the 'Voice of the West,'" Bergman said, "whether that was true or not."

Much of what was written about could be summed up in the eventual slogan of the populist Reform Party of Canada, "The West Wants In," which was popularized by Byfield.

Indeed, much of the Reform Party's policy was consistent with the political arguments made in the pages of the Report, and the Report gave the upstart party plenty of free ink to communicate those policies.

Manning, who was elected as party leader, said Byfield was very influential in the lead-up to the Reform Party's formation.

According to Manning, Byfield gave a voice to westerners who felt increasingly alienated by the NEP and by other moves from subsequent federal governments, like Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney's decision to award a contract for CF-18 fighter jet servicing to a company in Quebec, despite a similar, less costly bid made in Manitoba.

"Ted was just articulate on all of that. The ideas were floating around, the concerns were floating around, but he gave voice to it," Manning said. "He's a very good writer, very good speaker. He was giving voice to things that people were saying in the coffee shops."

Byfield's perspective, communicated in the pages of the Alberta Report and directly to would-be reformers, helped shape the direction of the statement of principles and policies eventually adopted by the Reform Party.

"That statement of principles was virtually the same from Reform to the Canadian Alliance, and then of course Stephen Harper and Peter MacKay did one more round of coalition building … to create the Conservative Party of Canada," Manning said.

"Ted's perspective, the statement of principles — even the Conservative Party of Canada today, over half the statement of principles are exactly the same ones that were written in those original Reform documents. Ted has a lot to do with that."

The Reform Party was eventually succeeded by the Canadian Alliance, which became the launching pad for future prime minister Harper, who in a letter signalled the influence of Byfield on the larger conservative movement at a reunion of magazine staffers in 2011.

"I sincerely regret that I am unable to attend your gathering of Report magazine alumni, and many others who were part of the 25-year journey from the birth of the Reform Party to this year's election of a national majority government for the new Conservative Party of Canada," Elise Byfield, Ted's granddaughter, read from Harper’s letter during the event.

A complicated legacy

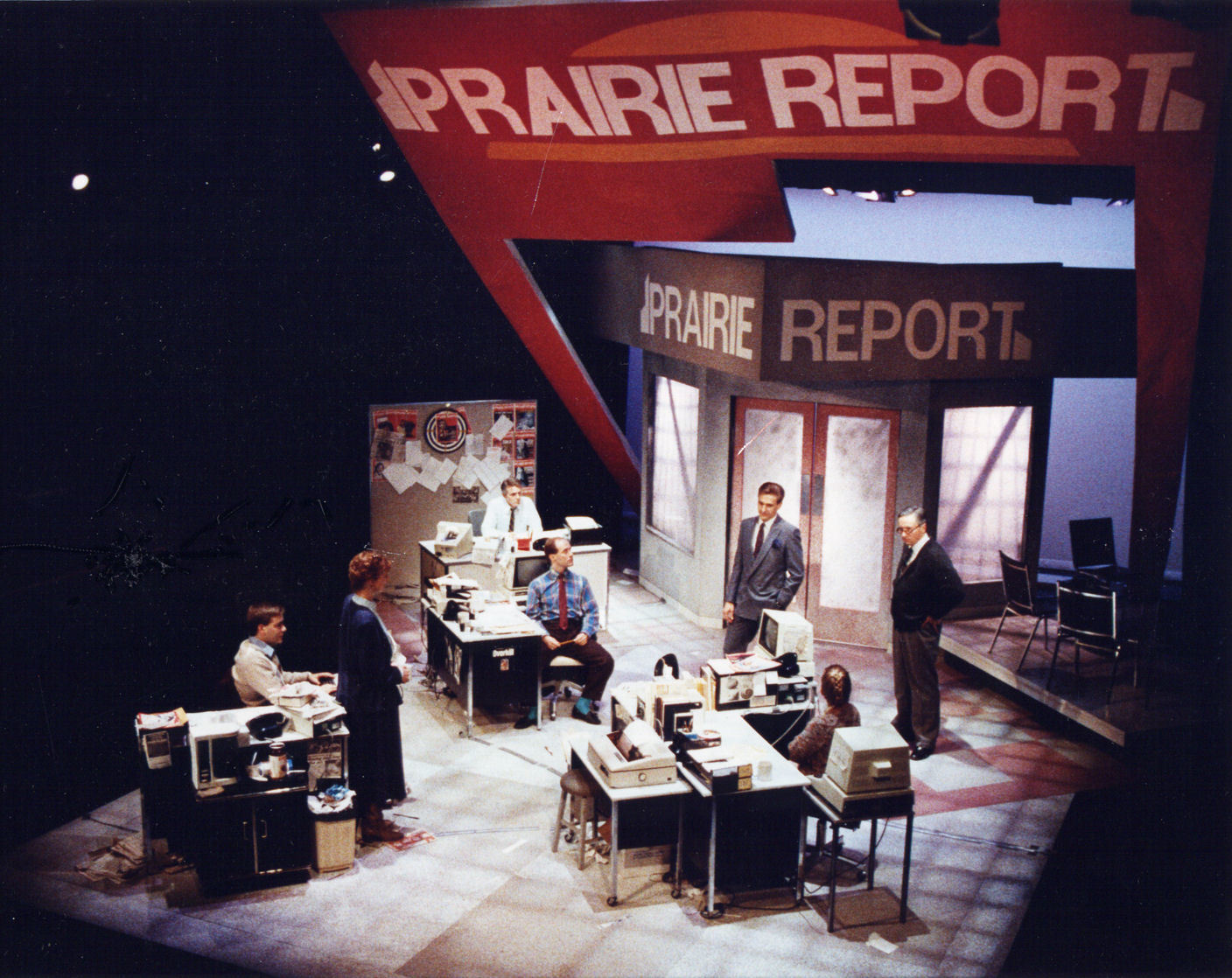

Joining the newsroom in 1981 to work in the books section, playwright Frank Moher was quickly struck by the newsroom — populated by smart writers and editors and the larger-than-life Byfield. But he soon found himself increasingly at odds with the magazine's politics.

"But I thought it was an obvious idea for a comedy," Moher said.

In Prairie Report, a play written by Moher, a fictional magazine is led by a character based on Byfield and struggling financially to keep going when "some slick guy from Toronto takes over."

"What happens in the play is you begin to see the movement from that old-school conservatism that Ted represented, paleoconservatism, towards another kind that, in my view, was nastier," Moher said. "It didn't care about the whole notion about Alberta's autonomy."

The Report, alongside its more traditional news content, was fiercely against homosexuality.

“If adultery or homosexuality is wrong in the sight of God, then all the task forces in Christendom aren’t going to make it right. If God is timeless and changeless, then human conduct considered wrong in the eighth century is just as wrong in the twentieth,” Byfield wrote in a column featured in The Book of Ted.

But some writers felt that some stories printed in the pages of the Report went beyond a religious perspective and became something vicious.

"We would sort of pick on — if there was a gay guy and something happened and he was to blame to something, that would become a big story because it showed how deviant or reprehensible gays were," said Mathew Ingram, who started at the Report in 1987 and now is chief digital writer for the Columbia Journalism Review.

"And the same thing with feminists or anyone else that was 'evil.' I don't feel good about it."

Such content illustrated one of Byfield's incongruities — publicly exhorting one point of view, where in private, another side might emerge.

Simons, who describes herself as a pro-choice, queer-positive, secular humanist of Jewish descent, said working at the Report helped crystallize her own viewpoints — and although Byfield's views were antithetical to her own, his complicated nature makes wrestling with her time at the Report a challenge.

"I want to be really, really clear about this. Many of the things that the magazine wrote were hateful. And they were hateful at the time," Simons said. "The fact that Ted Byfield was personally very kind to his gay employees, whom he really loved, doesn't take away from the fact that very painful things were written in the pages of the paper."

And yet, Simons said, she continues to have a deep personal affection for Byfield that "transcends any logic" — adding that the Report served as an important place in her own intellectual and moral evolution.

"He and I really always got on tremendously well. I can't explain that," she said. "I know people would say: 'How can you be friends with somebody who has views you don't agree with?' Because people are complicated."

Ted and Link

As the '80s wore on and the Report continued to struggle financially — Byfield had long relied on a few backers with deep pockets to bail out the magazine — he handed over the reins of the magazine to his son, Link.

While the elder Byfield was always strongly opposed to gay rights, some writers felt the Report became even more doctrinaire in its waning years.

"There was no debate. Link seemed very sort of, my way or the highway, and no quarter given on anything that had to do with anything even remotely ideological," Ingram said.

"My feeling was, as the magazine started to do worse and worse financially, they had to kind of become even more niche or double down on that stuff as a way to get attention or funding."

Such a direction was illustrated in a 1993 cover story with the headline “Can gays be cured?” It provoked a flood of critical letters and phone calls to the Report offices, and eventually a campaign against Report advertisers.

Colby Cosh, who today works as a columnist for the National Post, joined the Report newsroom in the 1990s as a researcher and eventually became a beat reporter and senior editor.

By that time, the elder Byfield had become a sort of legendary figure who would pop in to the Report offices once a week. But it was Link who was running the magazine on a day-to-day basis.

"To this day, I have a very high regard for Link's ability, and some of his characteristics as a boss," Cosh said. "As a writer, I think he's probably still underappreciated.

"He may have just come along too late to be appreciated in that way, or was considered too far-right to be within the scope of polite society."

Cosh said that Link's conversion to Roman Catholicism, in contrast to his father's Anglican and later his Orthodox faith, indicated that Link's own convictions set him apart from simply being "a clone of Ted."

"He might've been a little bit more shy in print than Ted was, and less able to project his own personality and his own background on the writing that he did for the magazine," Cosh said. "But as far as the intellectual underpinning goes ... I would not say he was less of a thinker or an arguer."

Parallels in 2020 Alberta

Bruce Foster, a retired professor of politics at Mount Royal University in Calgary, spent years studying the Alberta Report, reading each weekly issue.

"What it did is it amplified that western conservative position. And it did it very well," Foster said. "And I remember a quote from Byfield. He said conservatives, and I'm paraphrasing, but he said 'conservatives have always been regarded like the flatulent uncle who spoils the dinner party.'

"They said, 'We keep holding onto the same thing, holding onto the same values, and the world passes us by.'"

The magazine also provided a road map for Alberta politicians seeking to weaponize western grievances as a bargaining chip against Ottawa, Foster said. Such strategies have been employed in recent years, whether by federal Conservative MP for Calgary Nose Hill Michelle Rempel Garner laying out the Buffalo Declaration, former leader of the Wildrose Party Brian Jean calling for "four absolute necessities" or Kenney announcing the Fair Deal panel.

Even Jay Hill, Harper's former House leader, has argued that the West isn't getting a fair deal, recently becoming the head of the Wexit Canada party.

Such grievances — that the federal government regards the West as a supplier of raw resources to feed manufacturing industries in Central Canada while the West receives little in return — have been used by generations of Alberta politicians, Foster said.

"It's that same kind of appeal to one's emotions that Ottawa is a foreign power, the rest of the country probably hates us. We extract resources, and we're being punished for it.

"It is a potent argument. Whether it has a basis in fact is another thing entirely."

As Andrew Scheer's days at the helm of the federal Conservative Party were winding down, he warned the next leader on CBC Radio's The House in August that part of their responsibility will be the need to deal with growing western alienation. "I do think that there's a real angst out there, there's a real sentiment of frustration and people are getting ready to give up or throw in the towel," Scheer said.

According to Cosh, the historical argument around the Byfields can begin to be understood by tracing their influence on the Reform Party through to the modern federal Conservative Party.

"[The party] has been partly made with a lingering after-image of the Byfields in it," Cosh said. "So the question that I would ask is, did they fail or did they succeed? Did they succeed in re-integrating Western Canada with the rest of Confederation in a satisfactory way that will allow the country to exist as we know it for another century or two?

"Is the answer yes or no? To my mind, if Wexit is a failure, if Wexit doesn't get off the ground, then maybe they have to be given some perverse credit for that."

And while part of alienation relates to the ideology that Ottawa has left the oil industry behind, other former Report writers say western grievances are motivated just as much by those who hold moral positions they feel are not reflected in mass media.

"They never saw their values reflected, and they never heard anybody talk like them or address their concerns about the direction of society," said Steve Weatherbe, a former Report religion reporter and writer for the pro-life news website, LifeSite News. "That's what I got from readers."

That's a view echoed by Byfield today.

"There's been an attitude in regards to social values, resident in Ottawa more than any other place, that regards these things as trivial and nonsense, that is, the Ten Commandments, or whatever you want to call them — morality," Byfield said. "Without a solid moral basis in the law and behind the statute law, the country can't possibly survive."

Echo chambers

The Report ceased publication in 2003 after years of financial difficulty. It launched the careers of countless journalists, some of whom would go on to run and write for outlets that spanned the ideological spectrum — from Maclean's to the National Post, the Globe and Mail or the Western Standard.

Although he didn't agree with Byfield's traditionalist views, McCarthy said working at the Report gave him the ability to listen and understand the outlook of people with whom he differed — something he said takes on larger relevance as more and more people exist in their own echo chambers on social media.

"It's part of a bigger media discussion about what's acceptable, and how we treat people who come out with things we fundamentally disagree with," McCarthy said.

Even in his 90s, Byfield still writes about Alberta politics on his own personal blog. He said he doesn't know what his larger influence might have been on mainstream conservative politics — and considers worrying about such things a waste of time — but still fondly recalls his days running the Report.

"It was a glorious time," he said. "There was a certain gaiety around most city desks that were any good. I can remember reporters coming in off stories in which two-thirds of the story couldn't be written because it was libellous or something, and they'd be screaming [and] laughing at what had happened.

"Those were great days. And I guess they're gone forever. Who knows?"

More stories about the future of Alberta from The Road Ahead