May 13, 2018

The day started out just like any other: get up, get high.

But immediately after Stephen Miller watched his girlfriend pierce her skin and inject oxycodone, his life changed forever — and her life ended.

“She grabbed me by the arm and like dug her claws in and I looked at her and just the look in her eyes was enough for me to know that something serious was happening.”

He called the ambulance, and believes the last words she managed to mutter were about when it would arrive.

“I remember begging her, “Don't do this, don't do this, just stay with me.’”

“I just I couldn't believe that it was happening because I felt like reality was betraying me.”

She didn’t overdose while she was on a bender or at a party. She died just hours after waking up, injecting opioid leftovers from the night before.

Stephen and his girlfriend were addicts who liked to talk about quitting, but couldn’t commit to the task.

Together, they heated powdered opioids in a spoon, turning them to liquid that they could inject into their veins.

They were like pincushions, Stephen says.

Three years after her death, when he slips into a deep sleep, Stephen loses control of his thoughts and unwillingly allows his brain to replay the day his girlfriend died. Most times, the dreams are only loosely based on the true story and don’t stick to the plot, adding new characters and confusion.

Sometimes, in the nightmares, she’s still alive.

“It’s almost like I'm aware that she's dead but she's somehow still there.”

“The dreams can be different but it usually features some sort of overall dread… you know, survivor's guilt. I guess it’s the guilt that I'm still here.”

Becoming an addict

Years before addiction robbed him of his girlfriend, Stephen was a charismatic, charming guy with serious goals.

He graduated from high school in his small hometown of Marystown, and moved to St. John’s to study English at Memorial University.

“I always wanted to be published,” said Stephen, while on a recent walk through student housing and family neighbourhoods.

“I wanted to be an author... I've always just found myself having an immense love and passion for writing and reading and I just thought it would be really great if I could, you know, create things that people enjoyed the way I enjoyed novels that other people had written.

“But,” Stephen added, laughing, “I decided to switch majors to oxys.”

While living on campus, Stephen had trouble sleeping and self medicated with Percocets, a pain medication made up of oxycodone and acetaminophen.

Stopping on the sidewalk, Stephen gestures across the road, pointing out the house where his first drug dealer lived.

After asking the dealer for Percocets, the dealer told him he didn’t have any but could supply OxyContin.

“I was naive. I said, ‘No, I don't do OxyContin,’ And I guess, you know, they knew I was from a slightly different world from them and that I was a university student and I remember him laughing at me and just being like, “Oh, I thought you are supposed to be smart, you know, Mr. University.”

Stephen left with OxyContin, after being told it was a better bang for his buck.

That was the first day of his 10-year addiction.

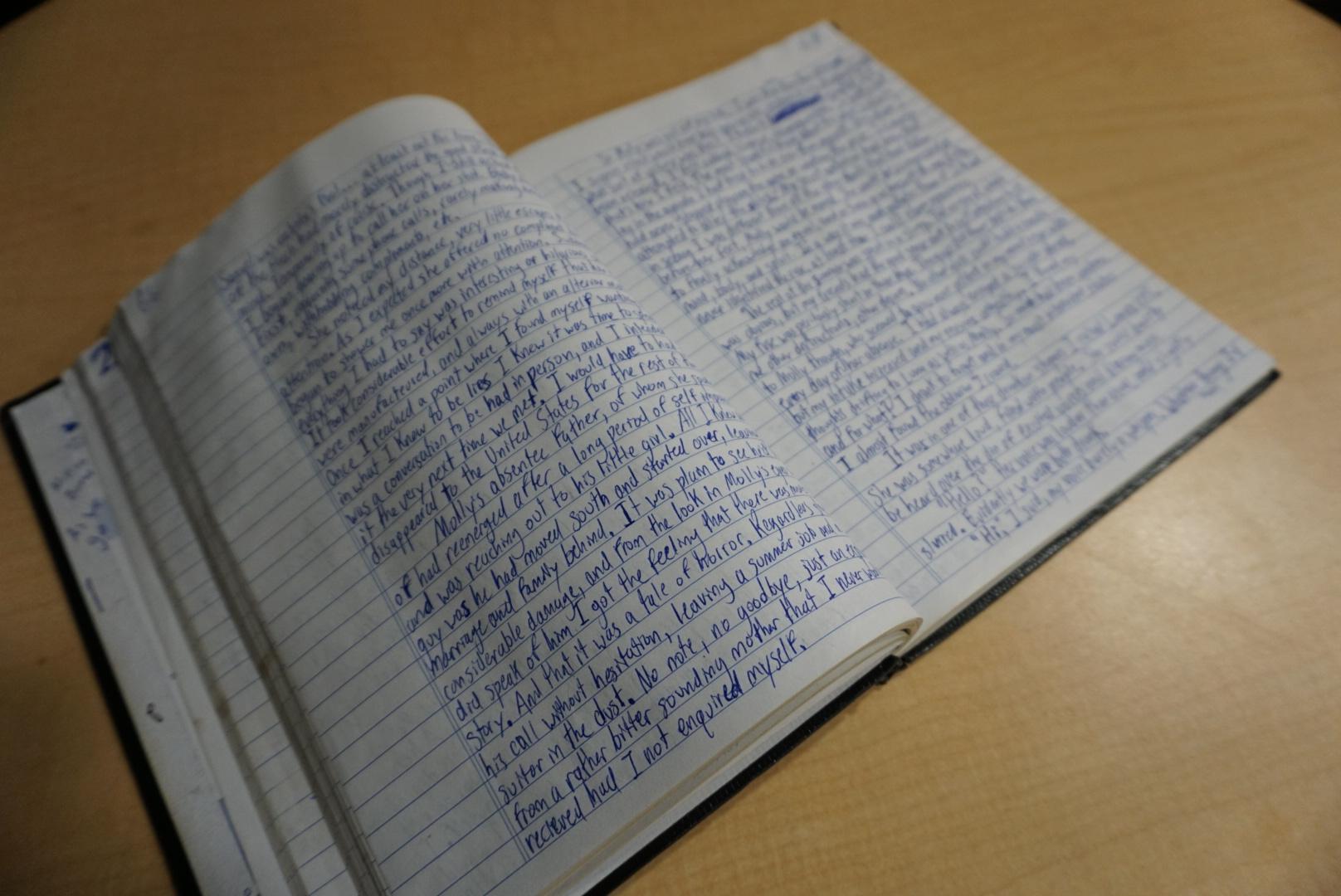

Novel excerpt from Stephen Miller, dated December 2013

Should I sober up long enough to take measure of my life, the result would invariably be a desire to escape. To escape the weight of my sin, the scope of my destruction, the downward spiral of my trajectory; but most of all, the state of my familial relations.

‘A menace, a troll, a gremlin’

“Once I went down that rabbit hole that was when things got really bad and it became less about choosing to do what I was doing and more about needing to do what I was doing so I wouldn't be sick.”

His parents paid for most of his drugs. Stephen did whatever he needed to get money from them to buy drugs. He’d lash out and threaten to end his life.

Terrified, and not wanting to push him over the edge, they usually gave in.

“I was able to take advantage of their love for me and I more or less financially ruined them. And I knew damn well what I was doing but I justified it, because I always said it was my last time.”

Stephen shot up in their home, as he lived in their basement. Upstairs, the family heard thuds when he passed out and bangs when he literally bounced off the walls.

“I was a menace, I was a troll, I was a gremlin.”

The family lived in dread during the seemingly unending cycle of addiction. Stephen’s mother, Juanita Miller, braced for what she thought was the inevitable: overdose and death.

“It was killing me to watch him be as sick as he was and to know that this little pill was doing it to him,” she said, while rubbing the tears from her cheeks.

“It was just crazy and I didn’t know if each night was going to be Stephen’s last night.”

Mourning while incarcerated

When she found out Stephen's girlfriend had overdosed and died, Juanita was devastated, and prayed it was the wake-up call her son needed to get clean.

Just days later, a police officer knocked on Stephen’s door. He was handcuffed and arrested. The charge: failure to comply with the terms of his probation. He had taken too much of his prescribed medication.

When the handcuffs were taken off at the police station, Stephen looked at the cramped cell he was about to be guided in to and he pushed and shoved to try to get away. He says it took four officers to get him in the holding cell. A second charge: resisting or assaulting a peace officer.

By this point, Stephen already knew his way around Her Majesty’s Penitentiary. He had already racked up a criminal record, with offences typical of a drug addict. He even knew many of the inmates.

But still, prison is no place to grieve.

“You don’t go to other inmates with your emotional problems. That’s just weakness and that's not a good thing to be doing in jail.”

An outlet for his pain, Stephen started to write. In notebooks mailed in by his mother, he wrote about loss, suffering, regret and violence.

Excerpt from Stephen Miller, dated February 2014

My first day on Unit 3, I learned very quickly why it was referred to as “The Jungle."

The inmate who invited me into his cell was a very intimidating individual; but so was everyone else on the unit, so I mistook his invitation as an olive branch. There were five of them in total, all eager to ask me about my medication.

I was seated when the first blow landed. Never saw it coming, “it” being a piece of metal that had been pried off the plumbing beneath the sink.

I recall wondering how long it would take for me to lose consciousness. I recall wondering if they would stop once I did.

While in prison, Stephen finished a novel. Most of the characters and events he detailed in the book are based on his real life, but he used fictitious names to protect the identity of those he wrote about.

Book club behind bars

When inmates saw him scribbling in notebooks, they were suspicious, accusing him of “being a snitch” to the guards.

They demanded to hear what he was writing. But after reading, they were hooked.

"It wasn't lost on me how odd it was to have, like, 20 burly inmates covered in jailhouse tattoos to be hanging on your every word."

“I would have 20 people in the cell at the end of the night and the guards would laugh and be like, ‘Oh, it's story time again, is it?’”

On story nights, inmates crammed into Stephen’s cell. The two metal bunk beds with thin mattresses served as the main seating area. But when there were more men than usual, the toilet and sink would double as seats.

“It wasn't lost on me how odd it was to have, like, 20 burly inmates covered in jailhouse tattoos to be hanging on your every word.”

His fellow inmates weren’t only fans, but editors too.

“I’m glad I’m not in prison now, but I gotta say, it’s hard to say no to writing when people are harassing you constantly like, 'When’s the next chapter?'"

Once word got out that Stephen had a way with words, he became an unofficial writer-in-residence. He read other inmates their mail, and would help craft the replies that would be mailed out to their friends and families.

‘I couldn’t go on the same way’

When Stephen walked out of prison, he carried his clothes and his journals and promised himself he wouldn’t be back.

He left with a permanent reminder of his girlfriend — a jailhouse tattoo of a teardrop on his finger, made possible with a staple from a magazine and a ballpoint pen. He’s grateful he didn’t listen to his fellow inmates and get the tattoo on his face.

“[Drugs] cost her everything, and because of her addiction, she won't accomplish all the things that she had the potential to accomplish," he said.

“I couldn't go on the same way. I just thought it would be an insult basically to her memory.”

On a day last fall, more than a year after his last stint in prison, I walked with Stephen as he set out to get his daily dose of drugs.

But at this point, the drugs are being prescribed: it's methadone, the replacement to the opioids his body had been hooked on.

The walk has become a symbol for his journey to sobriety. To get to the pharmacy, he passes the house that his first drug dealer lived in: a geographical reminder of his past life.

Along the way, he stops to admire the large, mature trees on the street — an act he even took the time to do when he was walking to buy illegal drugs.

Stephen gradually lowers his dosage of methadone, slow enough so he doesn’t experience strong withdrawal symptoms.

By the end of the year, he will complete the methadone replacement program, and become — for the first time in a decade — someone who doesn't take drugs.

Thriving on campus

Carrying a backpack, Stephen quickly walks past rows of lockers, reading the numbers on each classroom door he passes. This is his first day of class in the journalism program at the College of the North Atlantic.

After completing the first draft of his novel in prison, he set his sights on becoming a storyteller — and he’s got a pretty good story of his own to tell.

“Perspective is gained by every obstacle and struggle that you go through,” he said on his first day of class.

Classmates turned to friends, and teachers turned to mentors. Stephen is excelling in the program, was chosen as the class producer for their first radio broadcast, and frequently pitches stories in their class story meetings.

“When I was in the middle of my drug addiction, I would see people doing things like getting degrees or certificates and it seemed like life on Mars to me ... My life was just about literally finding and then doing drugs.”

‘No such thing as a model patient’

On a monthly basis, Stephen met with Dr. Jeff White, who is charge of the methadone program.

During rush hour on a crisp fall day, Stephen's new girlfriend, a pharmacy student, drives him to his appointment. Busy focusing on other items on his 'to do list', Stephen hasn’t gotten around to getting a driving licence.

In one of his last appointments before successfully finishing the program, Dr. White reminds Stephen that even if he appears to be a model patient, there’s really no such thing.

“I've had lots of so called model patients over the years and they turn out to be not so model once they finish the program and don’t have the methadone to help them,” said Dr. White.

Some patients can’t escape addiction and never finish the program. Methadone is sometimes a permanent replacement for other drugs. But Dr. White says it’s all about harm reduction, and as long as it’s keeping people out of hospital beds and courtrooms, he says it’s working.

“Stephen has showed that he’s stable and he has turned his life around to this point and we just hope that he can continue what he’s learned and just apply it to his everyday life after methadone.”

Excerpt from Stephen Miller, dated December 2017

Coming off methadone excited and terrified me in equal measure; I was losing my shackles, but also my safety net. A decade is a long time to walk on crutches.

'What are you at, Tuna?'

If he’s nervous of relapse, Stephen doesn’t show it. This meeting with Dr. White is one of his last before successfully finishing the program.

“What are you at, Tuna?” a man yells from across the clinic waiting room.

The man, wearing what looks like pajama pants, stands up and shakes Stephen’s hand. The two exchange a few words, but Stephen doesn’t stick around to catch up.

"Tuna" was Stephen’s nickname in jail. He was never exactly sure why he was given the name, but assumes it has something to do with him being a big guy. He jokes that he’s one of few overweight addicts, blaming that on his mom’s home cooked meals and generous portion sizes.

His new and old worlds don’t collide often but when they do — like when a former inmate yells his prison nickname while his pharmacist-to-be girlfriend waits in the parking lot — he admits it makes him feel uncomfortable and awkward.

“Now in life, I have these things that are more important. [My girlfriend], my career, my education, my relationship with my family — those are the incentives for me that are greater than drugs.”

“So if I can give anyone advice, it’s to find incentive to stop using drugs. Find a reason, find a life that's going to make you feel better than when you smoke or snort or inject.”

Stephen continues to write, and is currently looking for editors to help him publish the novel he penned in prison.

Excerpt from Stephen Miller, dated January 2018

Pride is a foreign concept to a needle junky, but it’s something I could get used to. Coming off methadone was not easy, the first week especially trying. My muscles ached in protest, my limbs restless, my nerves raw, the dull but constant throbbing of a brain that felt two sizes too big for the skull that housed it.