January 18, 2019

Donald Trump, would-be wall-builder-in-chief, may currently be the world’s most vocal defender of border walls as the best answer to unwanted asylum-seekers, but he is, in fact, late to the modern wall-building game.

Once home to one of the world’s most loathed walls, Europe has in recent years become a leader in building them: There are now border fences and walls in 10 European countries that together measure more than six times the length of the Berlin Wall, according to a recent joint report by the Amsterdam-based Transnational Institute (TNI), a research and advocacy outfit that supports international social movements, and Centre Delas in Barcelona. This within a continental alliance built on the idea of a borderless union.

And like Trump’s proposed wall, most of these formidable structures were built to keep people out.

The year 2015 was pivotal. Hundreds of thousands of refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq and parts of Africa arrived in what became Europe’s worst refugee crisis since the Second World War.

Citing inaction by European Union leadership, some member countries turned to the building of barriers as a favoured way to keep migrants out.

The building spree that year more than doubled the number of walls, from 5 to 12. In all, around 1,000 kilometres of walls and fences have been built in Europe since the 1990s, said the TNI report, titled "Building Walls."

European populist leaders have argued that barriers are necessary to protect their countries from irregular migration and, more crucially, from criminals and would-be terrorists among them.

“Every single migrant poses a public security and terror risk,” Viktor Orban, Hungary’s populist prime minister, said at a 2016 news conference in Budapest.

Orban, who has been called “the original Trump,” labelled the migrants passing through his country at the time as “Muslim invaders” who threatened Hungary and Europe’s Christian identity. He built barriers on Hungary’s borders with Serbia and Croatia.

The same arguments travel easily across European borders.

Barriers have also sprouted at the Macedonian border with Greece, at the Slovenian border with Croatia, the Bulgarian border with Turkey, among others.

When Austria erected a fence with Slovenia in reaction to the 2015 crisis, then-interior minister Johanna Mikl-Leitner said “a fence is not a bad thing. Anyone who has a house, has a garden and a fence” to help regulate who enters and who doesn’t.

And in Trump’s rhetoric, there are many echoes of European arguments gone by. Trump wanted Mexico to pay for his wall; Orban wanted the EU to pay for half of his border fence for the benefits he says the union reaped.

For both, walls and fences have proven a powerful political tool, says one expert.

“They look great on television, they look strong and impenetrable, and it suggests to the viewer ‘We, the government, is protecting you from something,’” Marcello Di Cintio, author of Walls: Travels Along the Barricades, said in an interview from Calgary.

But, he added, they are blunt instruments symbolizing an admission that builders are not interested in dealing with root causes.

“A wall is not a solution, it’s a surrender to the problem,” said Di Cintio. “A wall is a white flag. A wall says ‘We don’t know what to do so we’re just going to do this.’”

But can walls actually work?

“It’s a political platitude to say walls don't work — it’s like saying 'There's no military solution to this conflict,' which is almost always untrue,” says Tim Marshall, author of The Age of Walls: How Barriers Between Nations are Changing Our World.

Put together, Europe’s walls did interrupt the flow of migrants crossing the continent on foot en route mostly to Germany and Sweden in 2015 and 2016 — it did that by rerouting the flow.

Those who build them, says Marshall, “know they are not foolproof,” and in that there are lessons for the U.S.

“Governments realize that barriers can work in deflecting the flow of economic migrants and asylum-seekers away from their borders and towards someone else’s, and so as a short-term response to popular pressure they are a relatively cheap option,” says Marshall.

Nahlah Ayed describes the tense, desperate scene at the Serbian border with Hungary in September 2015. (CBC News)

At a time when division over immigration and migrants define European political discourse — and a time when Orban is openly calling for an anti-migrant takeover of the European Union — border barriers have proven popular both among ordinary Europeans and the politicians looking to win their vote.

Their supporters in Europe point to the almost immediate drop in the number of migrants inside each country as proof that they do work. They especially celebrate the Hungarian fences, and credit the Macedonian fence with Greece for shutting down the so-called Balkan route used by untold thousands to get to Western Europe.

But the drastic drop since the crisis in the overall number of migrants and refugees arriving in Europe is mostly attributed to European deals with, and pressure on, other countries to cut off the flow — from Turkey, host to some 3.5 million Syrian refugees, or Libya and farther south in Niger in Africa.

Some researchers and historians conclude that walls and barriers not only deflect the problem elsewhere — they also cost billions and endanger people’s lives in the process, because desperate people will always find another way.

Walls also always invite challenge, says Di Cintio, because “the impulse to build a wall is weaker than the impulse to cross one,” he said. For refugees and migrants, “it’s life and death.”

And it isn’t only asylum-seekers who persist in trying to find workarounds, but smugglers too, who in turn also charge more as their work gets more challenging — claiming more lives.

“The EU may celebrate lower numbers crossing borders,” says Nick Buxton, editor and co-publisher of the TNI report, “but when that is at the cost of higher deaths at sea, concentration camps in Libya, providing money to security forces of some of the worst dictators in Egypt, Chad, Sudan and so on, is that a cause for celebration?”

Europe's experiences show that fences and walls “can never solve the issues that cause people to leave their homes and are ultimately instruments of policy that are deadly in effect,” said Buxton.

Here is a look at four existing European border walls and fences, and how they’re working out.

SPAIN

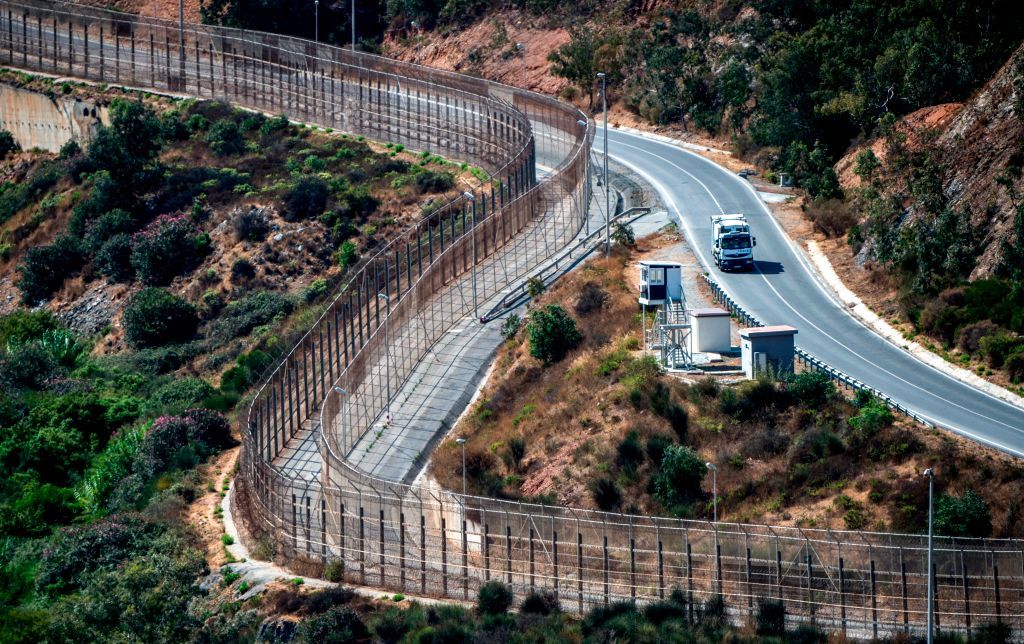

Europe’s two oldest border fences were built in the mid-1990s to surround the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla on the coast of North Africa. The fences cut them off from Morocco and from the only land border between Europe and Africa — attracting asylum-seekers and sparking constant European concern.

The fences have been continually improved since the 1990s with additions and fortifications.

The fence: CBC News visited Melilla last fall. The fence there is six metres high, and three layers deep. It is monitored 24/7 with infrared cameras, motion sensors and watch towers. Spanish police can respond to an attempted breach in under a minute. Moroccan authorities, supported by millions in EU money, also play a part by keeping asylum-seekers away from the fence.

The effect: Because the fences surround each city entirely, it takes a lot of personnel and money to monitor. The fences dramatically lowered the number of arrivals in Ceuta and Melilla.

But recently, as other routes to Europe have been blocked off, especially the sea route through Italy, Spain is still finding itself a favourite destination.

Ceuta and Melilla are also seeing more attempts to get over their fences, through them or around them — either on rafts at sea or smuggled through legal border crossings, folded inside the crevices of vehicles, sewn into mattresses.

Further, as in many other places, the fences themselves invite challenge. There have been several successful attempts to scale them, including a co-ordinated jump of several hundred people at Ceuta last summer, believed organized by smugglers.

HUNGARY

In 2015, Hungary became a key crossing point on the so-called Balkan route for hundreds of thousands of asylum-seekers making their way to Germany and Sweden. There were chaotic scenes at the border with Serbia, and at Budapest’s main railway station, where thousands of people slept waiting to get on a train to Austria and onward to their destinations. Hungary responded by building its first fence at the border with Serbia in record speed in 2015. It built another along its border with Croatia.

The fence: The first was initially a razor-wire fence. Since then it has evolved into a fence more than four metres high, electrified in parts and equipped with cameras. It is policed by so-called border hunters. Parts are also fitted with loudspeakers in several languages warning against illegal entry.

The effect: Hungary boasts that the wall has reduced the number of asylum-seekers there to nearly zero. The chaos at the border and railway station is gone.

Nahlah Ayed visits Hungary's fence on the Serbian border in September 2015.

In 2015, however, the flow of people, many if not most of whom had no interest in claiming asylum in Hungary, was simply deflected elsewhere – to Croatia and Slovenia, which until then had not been as affected by the large number of arrivals. It’s an example of how blocking one route to protect one country can negatively affect another.

Some U.S. proponents of Trump’s wall use the Hungary fence as an example of how well they can work. But Hungary’s wall gets too much of the credit given the number of asylum-seekers using the Balkan route was also sharply down — partly due to other countries on the route shutting down their own borders (see Macedonia below), and partly because the overall numbers to Europe were drastically down.

The fence, and Orban’s views on immigration, are popular. He recently won a third term as the country’s prime minister. But a mayor who lives near the fence told USA Today last year that while he accepted the need for a solution to the crisis, the fence was ineffective because migrants could still enter from the border with Romania.

“It serves no other purpose than political theatre. It should come down,” he said.

“Orban decided we needed this wall, and that is the only reason we have it.”

MACEDONIA

Macedonia was a main crossing point on the Balkan route for asylum-seekers arriving in Greece during the 2015 crisis. Inspired by Hungary’s example, Macedonia decided to build a fence that was completed in 2016 that helped to shut down the Balkan route. Initially only refugees from Syria, Iraq or Afghanistan could go through to continue their journeys. A group of asylum-seekers intent on making their way through broke through the fence. The authorities resorted to tear gas and rubber bullets.

The fence: The initial metal fence was about 30 kilometres long. The government then erected a second, longer parallel razor-wire fence.

The effect: The fence is where hospitality morphed into hostility, and where the EU put its foot down to protect fortress Europe.

The fence initially helped create a bottleneck, as well as Europe’s largest refugee camp, where up to 15,000 people were stranded at the border between the two countries. That camp was eventually dismantled by Greek police, but thousands are still stranded in government shelters and on the Greek island of Lesbos, where conditions have deteriorated and where people have no prospect of leaving.

Macedonian police fire tear gas on migrants storming Greek border, February 2016. (CBC News)

Many have also turned to Bosnia as a possible route deeper into Europe, and the country has struggled to contain the flow.

On the other hand, while negatively affecting Greece and the asylum-seekers trapped by the fence, it also helped stopped the march of thousands of asylum-seekers on the Balkan route, which benefited other countries. That spurred some smugglers to find other ways of getting asylum-seekers into Europe, and the Italy sea route saw a surge in the number of them arriving on Italy’s shores, primarily from Libya. Many more people died at sea.

The fence has been patrolled with help from other EU countries. One recent Associated Press report said the country still saw more than 6,500 people crossing its borders in the first half of 2018.

FRANCE/UNITED KINGDOM

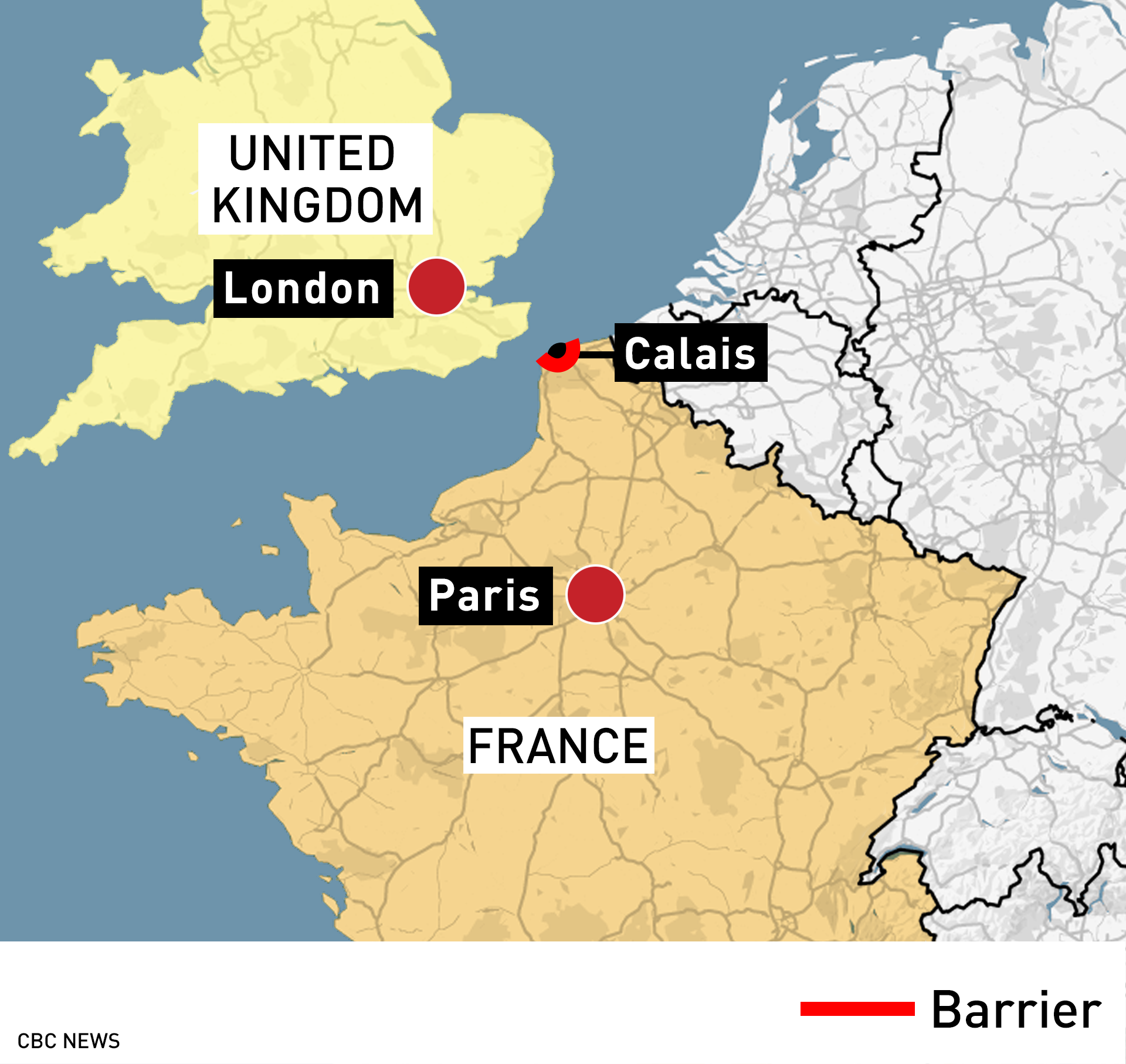

Thousands of asylum-seekers have flocked over the years to Calais, a French city that sits on the English Channel that separates mainland Europe from the United Kingdom.

They came in the hope that they will be able to smuggle themselves across to the U.K., where many of them say they have family.

The camp dwellers lived in terrible conditions in what was dubbed the Calais Jungle as they waited and risked their lives daily to get into a truck, a ferry or through the train tunnel that links the two countries.

The U.K. decided to build what was later derided as the Great Wall of Calais, to prevent asylum-seekers from accessing the route.

The Calais camp was dismantled by French police and burned to the ground. The wall was completed in 2016 — about two months after the camp was destroyed.

The wall: It is one kilometre long, four metres high, and made of concrete. France and the U.K. shared the cost.

The effect: The number of asylum-seekers getting onto trucks dropped dramatically, and it’s rare to hear of asylum-seekers getting into the tunnel.

But the wall has not deterred others, and many soon returned to the Calais area to try to find ways to get to the U.K.

In recent weeks, Britain has also seen a flurry of boats crossing the Channel bringing migrants ashore — five separate boats on Christmas Day alone carrying Iraqis, Afghans and Iranians. The authorities blame criminal gangs. Smugglers have clearly adapted once again.