November 11, 2020

From deep in the back of the closet came a cardboard box, filled with family heirlooms and precious documents: a family Bible stuffed with newspaper clippings about births,deaths and marriages, crumbling postcards, faded photos, old silver coins.

My father’s hand pulls out colourful cloth, with bronze stars and silver discs attached.

“What are those?” I ask.

“War medals,” he mutters, pushing them aside.

I inspect them with great curiosity, letting my finger run over all the intricate details.

The dates — 1939 to 1945 — seem impossibly old to my eight- or nine-year-old self.

The France and Germany Star. A tarnished silver medallion with a very fierce lion on it.

Then there were the photos, tucked in the back of a frayed booklet, the Soldier’s Service Book.

I see my father’s name in smudged ink.

"Don’t ask him about the war.”

There are black-and-white photos of men I did not recognize. There were trucks and jeeps and what looked like a tank.

Tiny photos, faded, worn and blurry.

“Is this you? Were you in the war?” I ask.

“Yes.”

“Who are these people?”

“People that were in the army with me.”

My father stopped at one particular photo and said, rather quietly, “He didn’t make it.”

I was curious. Why were these mementos kept away in a closet? What happened to him so long ago?

My father had been wounded during the war, he had a deep scar on his jaw and on any hot, shirtless summer day, you could see the scars on his back and upper arms.

“Don’t ask him about the war,” my mother would later tell me. And so I didn’t.

We would let him tell it in his own way and in his own time.

A photograph cherished, a mission inspired

Today, I am standing at the window of my home office and watching tiny flakes fall, thinking about a cold and snowy battlefield in Holland some 75 years ago.

Where do I begin to tell this story, about a mystery that took all these years to unfold? It’s a complicated tale, with many twists and turns and unlikely coincidences that had to happen to recover a soldier lost both to time and tragic circumstances.

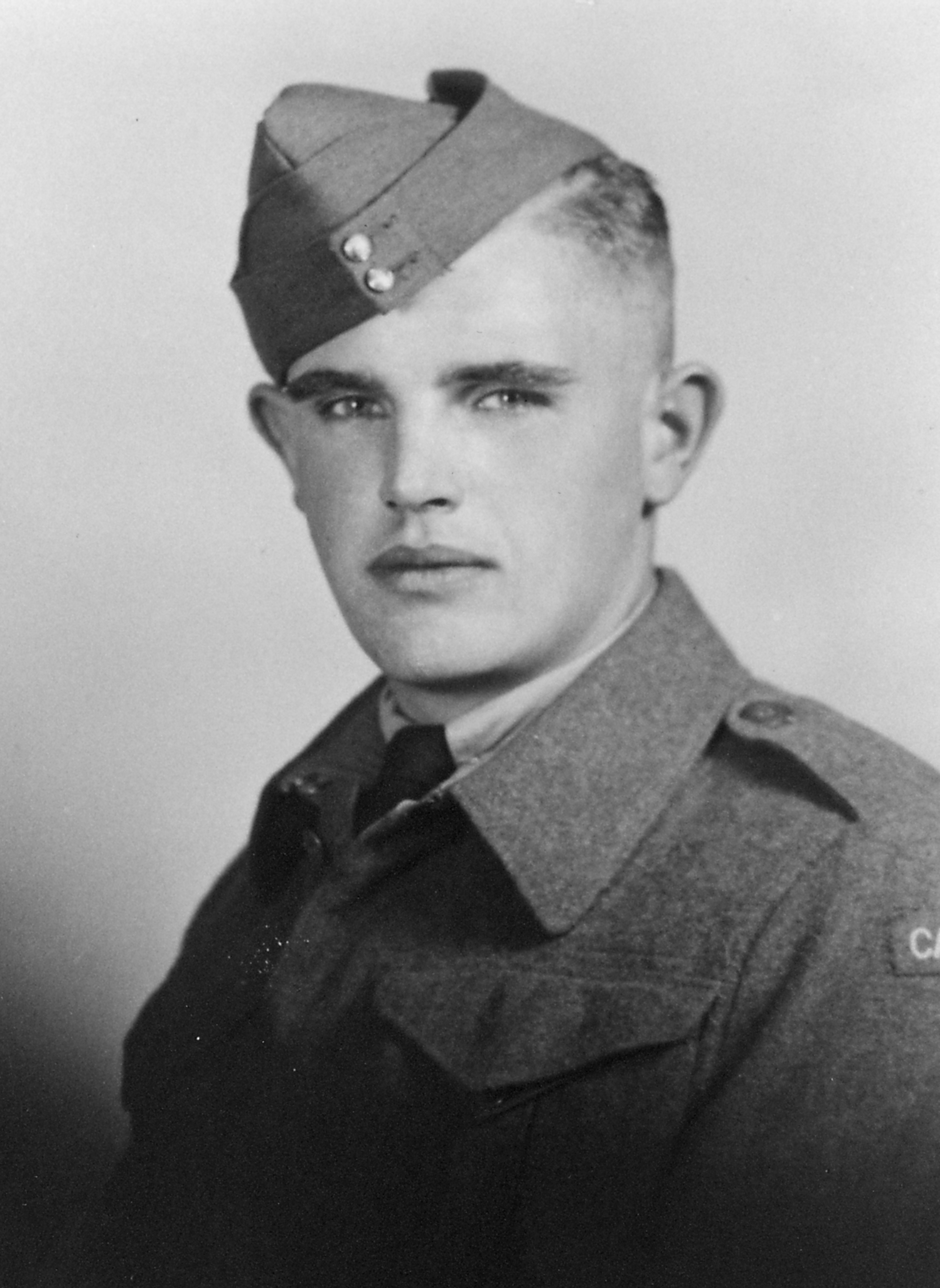

My dad's best friend in the army was a trooper named Henry George "Archie" Johnston.

They went through basic training together and served side by side in Holland in the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment, nicknamed the Kangaroos.

Johnston was killed by German mortar shell. His final burial place remained a mystery for decades. His photo was one of the few things that my father kept.

On those rare occasions that my father would talk about the Kangaroos, he always made a point to mention Archie Johnston. As an adult, I kept a copy of Johnston’s photo, always wondering if his family had a corresponding photo of my dad in uniform.

That photo, and my dad's unshakable memory of his friend, fueled my curiosity about the Kangaroo Regiment. I decided to make an effort to capture and record its history before it was lost for good.

I tried finding the Johnston family several times over about 15 years, beginning in the late-1990s.

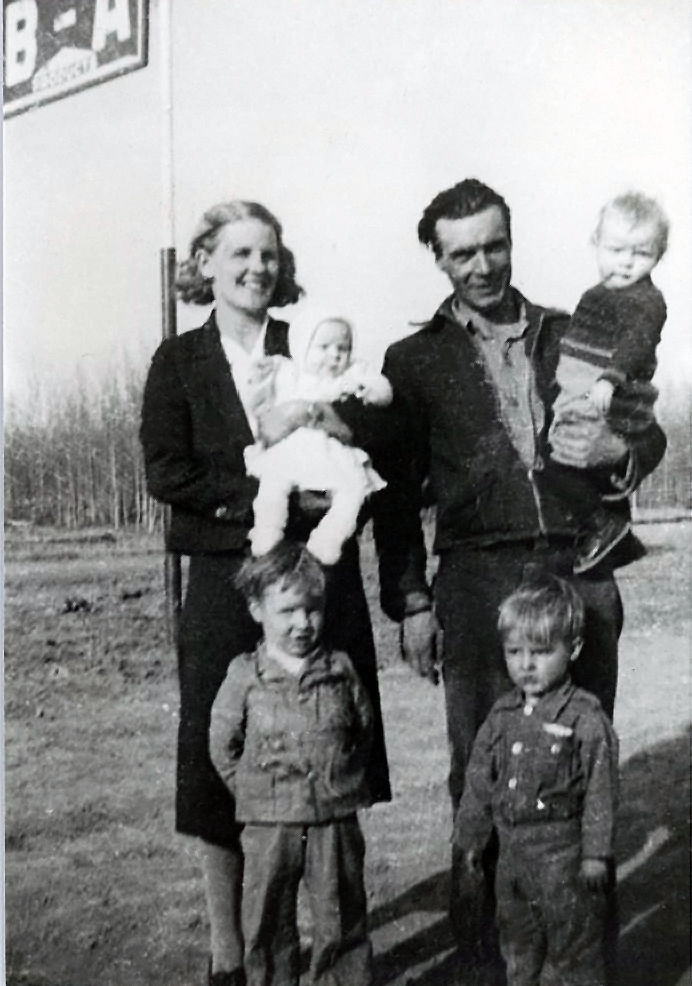

Johnston left behind a widow and four small kids, including a nine-month-old daughter. His widow had remarried, before dying in 1983, but the trail on the surviving children ran cold.

Then, in 2012, came the phone call.

Finding the family, uncovering a mystery

It was Gord Krebs, who is married to Johnston’s granddaughter. He and his family had just returned from a trip to Holland where they had tried to visit Johnston’s grave at the Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery.

But Johnston had no grave. His name was simply memorialized on a wall for the missing.

Krebs had been referred to me by war museum staff in Holland as a possible source of information.

“What was your grandfather's name?” I asked.

"Henry George Johnston," he replied.

You could have knocked me over with a feather.

After a very long pause to regain my composure, I told him I knew all about his grandfather and so did my dad.

A long conversation followed and we arranged a family reunion of sorts. Members of the Johnston family were able to meet my dad shortly before his death and talk with him about "Archie."

As I had wondered for so many years, their family did have photos of my dad. Not just one, but two. The search was over, or so it seemed.

Then came the text message in 2018.

A Dutch colleague, Ivo Wilms, had been researching some downed airmen and came across a clue about Johnston’s final resting place.

Johnston had been killed in the village of Baakhoven, and Wilms had found documentation about the burial of four Allied soldiers.

One of the bodies that had been buried as an “unknown” was exhumed in 1947 to be reinterred at the official war cemetery in nearby Mook. Upon exhumation, the remains were identified as Trooper Jake Dyck of the 1st Canadian Armoured Personnel Carrier Regiment.

Wilms, who was very familiar with the battles of the Kangaroo Regiment, didn’t recognize Jake Dyck’s name as a casualty and a further search of records confirmed the suspicion.

Trooper Jake Dyck of Winnipeg had survived the war and passed away peacefully in 2007.

I had never seriously entertained the idea that Johnston’s body had been properly interred, let alone the idea of finding that grave 70 years after the fact. Was this the evidence we needed to prove that the unknown grave at Mook was actually Trooper Johnston?

Wilms and I both felt it could not be a coincidence.

I made inquiries to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which was able to tell me that the misidentification came about because of a silver identification bracelet — marked with Dyck’s name and service number — that was found on the body.

As is the policy of War Graves and the army’s Casualty Identification Program, bodies already interred at a war cemetery will not be exhumed again for DNA analysis. It is up to investigators to build an overwhelming and undeniable body of circumstantial evidence to prove a grave’s identity.

I turned over as much documentary evidence as I could. Finding my case to have merit, investigators began the lengthy and exhaustive record check.

They surveyed all the Canadian casualties with no known grave within a 100-kilometre radius of the Johnston battlefield. Ultimately, they concluded that it could be no one else but Johnston.

The findings were approved by the Casualty Identification Review Board in November of 2019 — a 22-month-long process — and the family was officially notified in February of 2020.

Good work takes time.

A rededication ceremony was supposed to take place in May, coinciding with the 75th Anniversary of VE-Day, but the COVID-19 pandemic has altered that timeline.

Johnston’s grave will likely get a new headstone soon but an official rededication with the family will have to wait.

Spider-web of improbable connections

Today, I think about Jake Dyck’s silver bracelet, found in the grave with no explanation as to why it was there.

Did Henry Johnston find it and pick it up? Did the men exchange tank suits at some point and the bracelet was left behind in a pocket? Or was it put there on purpose?

Johnston’s army-issue identity discs were not on the body, likely destroyed in the blast that killed him. Perhaps a prescient young Jake Dyck thought of the bracelet as a way to tie the body back to his regiment when they had to leave Johnston’s body behind.

I’m neither a religious or superstitious man, but I cannot help but think that it was more providence than mere happenstance that brought us to this happy conclusion.

I think about all the actors in this story and the spider-web of improbable connections made over seven decades to find Henry Johnston.

The memory of a man’s sacrifice, passed from father to son, which inspired an empathetic (and quixotic) guardianship of memories of a long-forgotten regiment, which led to the family the son was seeking.

And then, there is a seemingly random meeting of a like-minded researcher halfway around the world who, years later, rediscovers the tiniest of clues left behind on a snowy battlefield in 1945 and heals the emotional scars of two families.

I recall once, as a teenager, after attending a Remembrance Day ceremony at school asking my father why he did not participate in annual commemorations of Nov. 11. His response was sharp and matter-of-fact.

“I remember every day,” he said.

And now so do I.

But I have good reason to smile when I do. As Ellen Rowe, Johnston’s youngest daughter, told me last week, “Sadness has been replaced with pride.”