March 10, 2019

It was the 1997 launch of the movie Titanic, of all things, that led Joan Planedin to a startling discovery.

The Langenburg, Sask., woman had always known her great-great-grandfather was working on the ship and died when it sank, but the blockbuster hit inspired her to investigate further.

"We had no idea until we started researching how much of a tragedy this family had been through," Planedin said.

Growing up, she'd been told William Mintram Sr. was coming to Canada to find his sons, including William Jr., her great-grandfather. She knew they'd come here alone as children, but didn't know why. In her research, she learned her great-grandfather had seen his own father murder his mother.

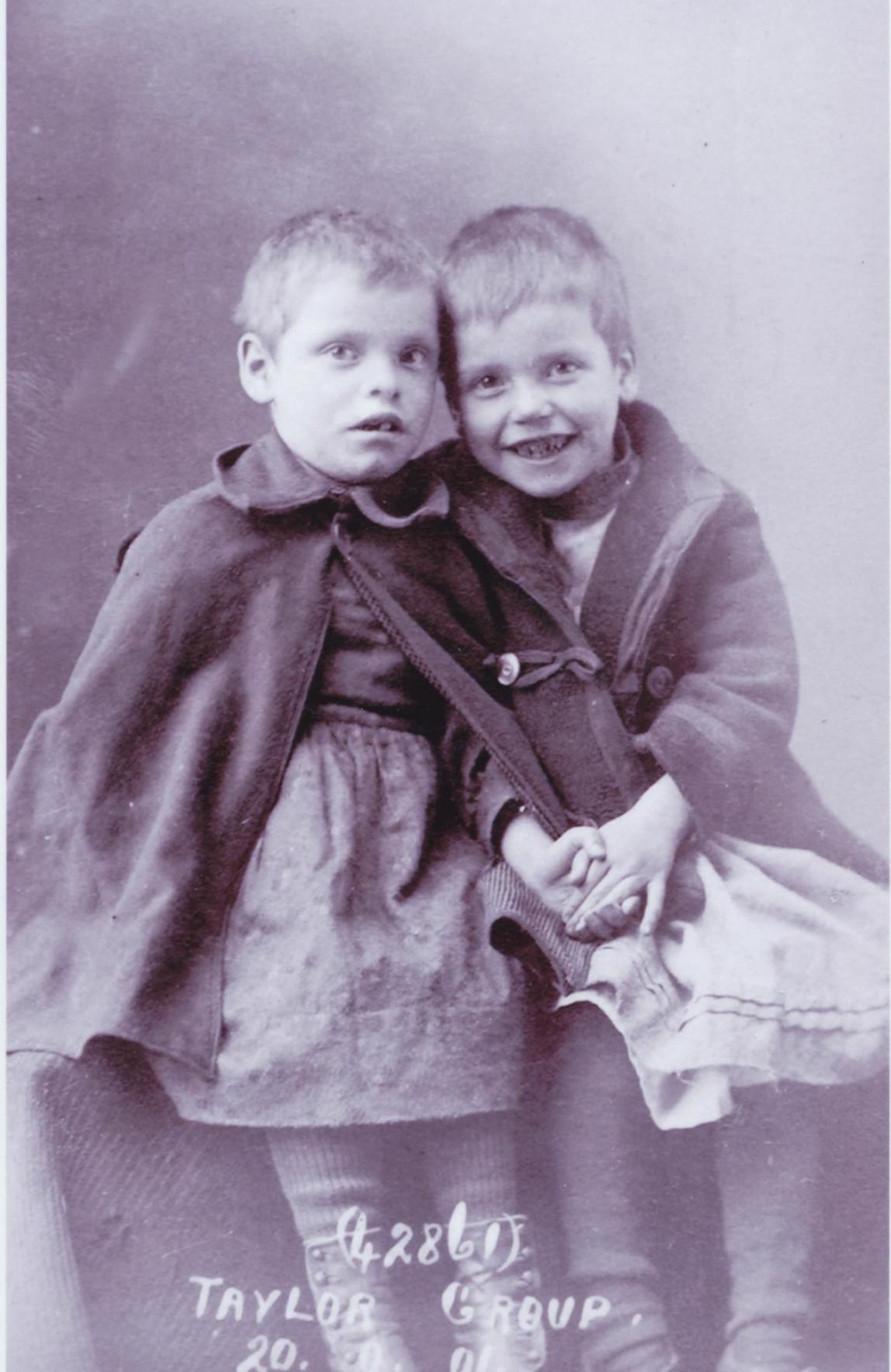

When his father went to jail, William Mintram Jr. and his siblings were sent to Canada — three boys among tens of thousands of British "home children" sent overseas as indentured labour from the late-19th to mid-20th centuries.

According to the federal government, more than 100,000 British children came to Canada between 1869 and the official end of the program in 1939. They were sent by the children's aid organizations responsible for them, and were scattered through indenture contracts to farms and homes across the country.

A small number of the children were orphans: Lori Oschefski, head of the British Home Children Advocacy and Research Association, says it was around two per cent. The rest were from families that had fractured or fallen on hard times, she said, and many had relatives who still wanted to care for them. All were deeply impoverished.

When they arrived, they were put to work. In Manitoba, that often meant farming: roughly 800 boys 14 and older passed through a training farm run near Russell, 310 kilometres northwest of Winnipeg, before being sent to farms as indentured workers, Oschefski said.

That's effectively where the accountability for aid organizations ended, says Bob Huggins, an Ottawa-based filmmaker whose father was a home child. Little was done to check in on kids' living conditions, he said, which ran the gamut from his own father's experience of being lovingly integrated as a member of the family to darker stories of exclusion and abuse.

Records from across Canada tell stories of children forced to sleep in barns or forbidden from eating with their employers' families. Oschefski's organization estimates roughly 65 per cent were abused. Her own aunt, Mary, was whipped, beaten and moved 20 times in less than eight years. She was 14 when she gave birth to a stillborn baby.

"I think it's a huge injustice that was done to these children, and I think that we have to speak out about it," Oschefski said.

"We have to make sure that Canada knows about these children and their part in our history."

An industry ‘fed children'

The Russell farm was run by Barnardo's, the most high-profile home children organization. Named for its founder, Dr. Thomas Barnardo, it operated across Canada and the U.K.

The Russell farm opened its doors in 1888. The first party of 50 boys arrived in April of that year to a large-scale operation, which included a dormitory for up to 100 boys, acres of farming land, a creamery and more. Local newspaper ads from the time encouraged farmers to apply for labourers.

"To the Canadian government, this was an opportunity to get much-needed population and much-needed farm labour, because there was a real shortage at farm labourers," said Ralph Jackson, whose grandfather Harry Jackson came to Winnipeg at 16.

"From the British standpoint, it was really kind of doing away with a problem [they] had, sending it abroad."

Oschefski believes the program was born of good intentions, as overburdened children's homes in the United Kingdom struggled to find ways to care for the rising number of children in need.

But philanthropy wasn't the only motivation — there was money to be made by sending the kids.

Archival records indicate the Canadian government started paying home-child organizations a bonus of $2 per child in 1875, and Oschefski says British governments made similar payments.

"It was all a money-making enterprise that [Barnardo] had going in the U.K. They published books, they published magazines," she said. "And over here in Canada … they actually sold a lot of this stuff to the kids."

In some cases, children were sent with their consent, or that of their parents. In others, she said, impoverished parents sent their children to homes for what were supposed to be temporary stays, only to have them sent away without the parents' knowledge.

"He really built himself a business," Oschefski said of Barnardo. "He built himself, like, an industry, and that industry had to be fed children."

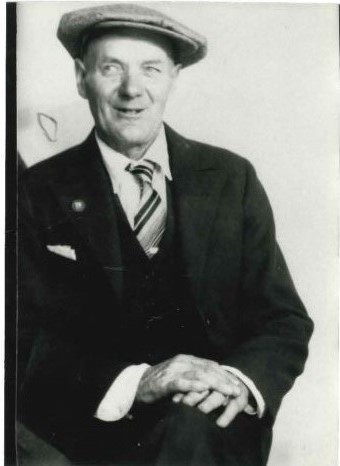

Ralph Jackson's own grandfather, Harry, came to Canada as a home child by choice when he was 16, after the death of his mother. He wasn't a "Barnardo boy": he was sent to one of a handful of receiving homes in Winnipeg run by other home-child groups. In his case, it was one called Shaftesbury Homes.

Jackson doesn't know what his grandfather's living conditions were like in Canada. Like many Canadians — Oschefski estimates there are up to four million descendants of home children here — Jackson grew up with no idea about his grandfather's history. Most home children were reticent about their pasts with their families, he said, out of a shame they learned from Canadian adults when they arrived.

"[Public sentiment was] vilifying children, to the point where ... after a while, they don't want to talk about who they are, because they're ashamed," Jackson said.

In an 1891 journal article, then-Toronto MP Frederick Nicholls called the children "human warts and excresences."

"These 'waifs and strays' are tainted and corrupt with moral slime and filth inherited from parents and surroundings of the most foul and disgusting character, and all the washing and clean clothes that Dr. Barnardo may bestow cannot possibly remove," Nichols said.

"There is no power whatever that can cleanse the lepers so as to fit them to become desirable citizens of Canada.”

Among it all, Oschefski sees Barnardo's Russell training farm as a "shining star." She feels her own grandfather was genuinely saved from poverty by being sent there.

Joan Planedin believes her great-grandfather's experience was also positive at the Russell farm. She says William Mintram Jr. was "one of the lucky ones" — after his time at the Barnardo farm, he went on to the loving Westman family on a farm near Churchbridge, Sask.

She says her family's story, and others like theirs, speak to the resilience of the home children themselves.

"In many cases they thrived regardless of their conditions. They went on to have their own families, and their families went on to have their own families, and were really deeply woven into the fabric of Canada," she said.

"I feel that these children need to be celebrated for what they have overcome."

‘They deserve to have their stories told'

After Barnardo's death in September 1905, the Russell training home closed and was later demolished. Now, the site is marked with a cairn.

Planedin is planning to put together an exhibit memorializing the Russell home for the community's library.

The story of home children is also shared in exhibits at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg. Jodi Giesbrecht, director of research and head curator at the museum, said it's important to commemorate their experiences, even if that's hard for Canadians to come to terms with.

"It leaves us with a more honest and authentic understanding of Canada as a nation, in terms of where people have come from — the sort of range of experiences of Canadians," she said.

"Even if it's challenging and it's difficult, it results in a richer understanding of Canadian history."

To at least a couple of Manitoba home-children descendants, though, the museum's exhibits don't go far enough.

Roberta Horrox and Suzanne Mozdzen both said they'd reached out to the museum asking to see expanded materials on home children. Mozdzen wants more descendants to learn about their history, which she suspects many don't know about.

"Nobody really knows this story," said Mozdzen, whose grandmother was shipped to B.C. from Ireland when she was only two years old.

"I really think that we really need to understand the formation of this [country]. Hundreds of thousands of people have this background, and they don't even know it because the records are so hard to find."

In a written statement, Giesbrecht said the institution deeply appreciates Canadians' passion for human rights history, but can't accommodate all the suggestions it gets.

Oschefski said she wants to see an apology from the federal government itself, in addition to a 2017 apology from the House of Commons.

"It's a critical part of our nation's history. These children are little nation-builders. This country was built on the backs of these children," she said.

"They deserve to have the recognition for that. They deserve to have their story told."