December 17, 2020

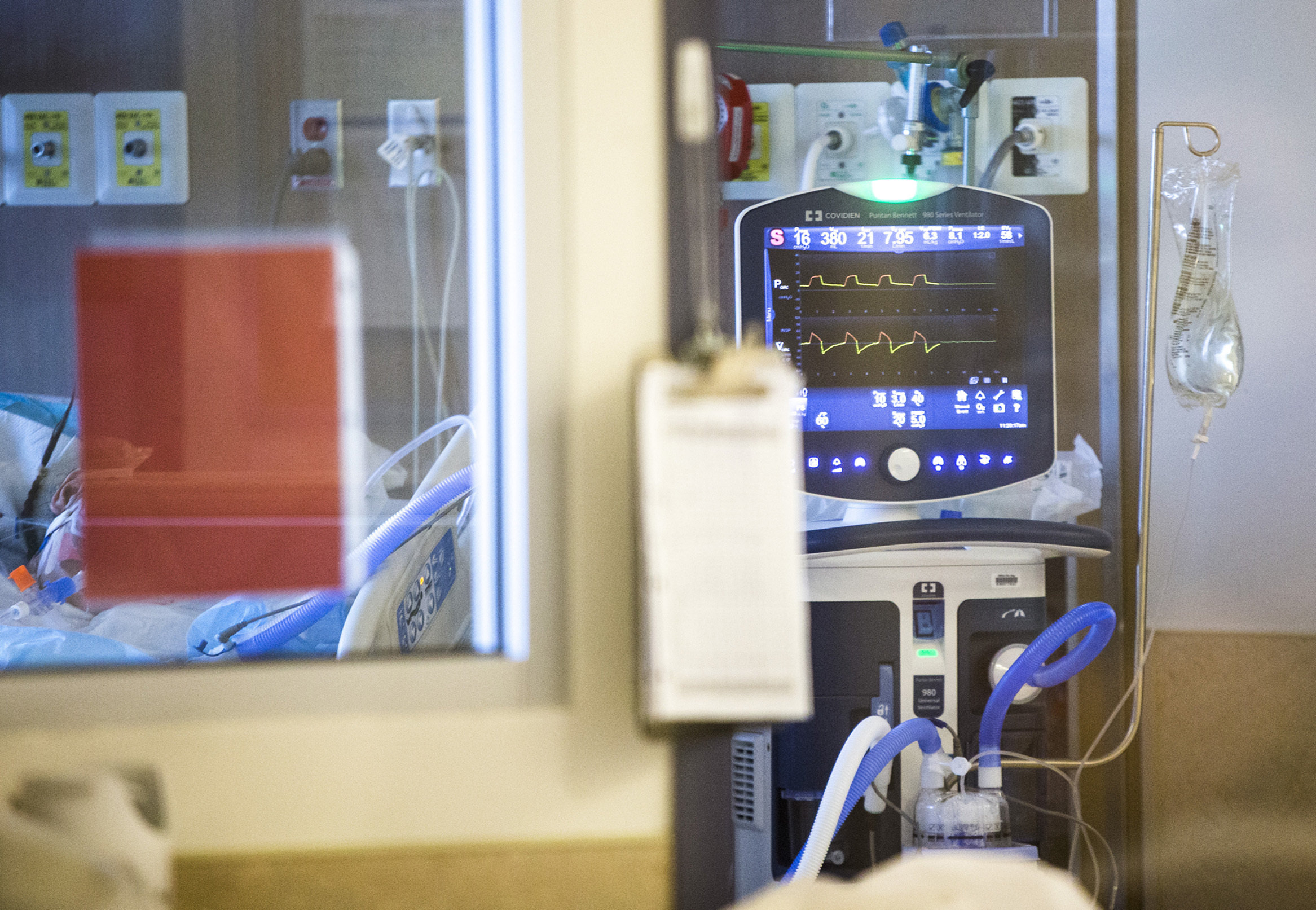

A health-care worker grips the door frame and peers into a room where one of Winnipeg's sickest COVID-19 patients is fighting for her life.

"Is she OK in there?" she asks.

The patient, who is unconscious on a ventilator, will need more sedation, a colleague says.

Hers is one of many lives teetering on the brink.

Nearby, a nurse and respiratory therapist find a rare moment in the chaos of their workplace to stand still. They watch a man they care for, who may only be alive because a machine is pumping air into his lungs. His breathing is laboured — the movement of his chest stutters, a sign he may have been momentarily weaned off the ventilator to see if he could breathe on his own.

The weary staff are living the scenario public health officials tried desperately to avoid by pleading with Manitobans to stay home when COVID-19 cases started spiking. Every bed in the medical intensive care unit at the Health Sciences Centre is full, and every ventilator is in use.

These scenes in glass-cordoned rooms are playing out day after day, at a frequency Manitoba's health-care system cannot endure indefinitely.

"The hospital system, no matter how well it's running, no matter how well we've been able to uptick the capacity, can't sustain this," said Dr. Bojan Paunovic, an intensive care physician and the provincial lead for critical care.

To date, the virus has infected more than 21,000 Manitobans and killed more than 520. For weeks, hundreds of people have been in hospital with the illness, leading to a scramble to open up new intensive care spaces.

As of last week, health officials said Manitoba's critical-care program was operating at 196 per cent of its pre-pandemic capacity.

HSC, the province’s largest hospital, has been forced to reinvent itself to avoid buckling under the pressure.

It turned a surgery unit into a ward for COVID-19 patients. It added beds where there weren't beds before.

Not only is the 20-bed medical intensive care unit at HSC — for the most critically ill patients — full, but so are two separate six-bed units created specifically for the pandemic. The hospital fashioned another 15-bed intensive care unit for COVID patients, which is partially occupied this morning.

WATCH | Meet the people involved in HSC's COVID-19 response:

A rare look inside the Health Sciences Centre during the pandemic, a Winnipeg hospital morphing to meet the demands of a surge in COVID-19 patients.

“The number of these situations where you're seeing people that are not responsive to therapy or are deteriorating are just an order of magnitude higher than before,” Paunovic said.

On Dec. 8, Shared Health, which oversees Manitoba’s health-care system, granted a rare glimpse inside a hospital waging war with the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic. The interviews and footage recorded by a team of journalists were shared among Winnipeg media outlets.

On that Tuesday, the 245 new cases announced were the lowest in two weeks, a rare sign of hope in an unrelenting pandemic. But the daily count has remained at hundreds of positive tests each day — leading to the unsustainable number of people needing care.

At HSC, which is facing the brunt of the crisis, there are not only more patients in the intensive care units than at the pandemic’s beginning, but they’re getting younger, Paunovic says. He’s increasingly seeing middle-aged patients, along with seniors.

Most of the patients who come to the hospital are experiencing respiratory failure, which translates into needing oxygen and ultimately mechanical ventilation.

ICU workers are also seeing "extra inflammation and sometimes significant scarring of the lungs above and beyond what we've usually seen with viral pneumonias," Paunovic says.

"That translates into people needing to be on the ventilator longer than we've usually seen in other illnesses, and [patients] take longer to recover even when they get off the ventilator."

If that happens at all.

"It's still fortunately common that they can be weaned from the ventilator," Paunovic said.

"But given the numbers [of COVID patients] we're seeing, we're seeing a significant number of patients who can't be, and their lung damage is such that they would never be.”

Those patients are transitioned to palliative care, to ease suffering in their final hours or days.

'What we don’t have is staff'

It's nine in the morning and hospital beds are as coveted as they have been for months.

As part of the pandemic response, health officials meet virtually every morning to discuss the management of an overflowing hospital.

In a meeting room, charts and graphs are beamed onto a white wall for people on the call, like a scene out of a science-fiction movie.

Some rows are coloured in red, which represents an overcapacity unit.

They can tell the number of suspected COVID-19 positives across the HSC site, broken down by unit.

“Right now on our children’s unit, we have three suspect positives,” Jennifer Cumpsty, acting chief nursing officer for HSC, told a visitor later in the morning.

The problem, says Cumpsty, isn’t space in the hospital; they can keep finding rooms to put more beds and more COVID-19 patients.

“What we don’t have is staff,” she said. “That is our limiting factor.”

To address that, teams of specialists led by critical-care nurses have formed to care for patients befallen by the virus.

These teams include staff who would otherwise not work in critical-care units, such as the nurses in the GD-2 unit — an orthopedic surgical ward before the pandemic, said Anna Marie Papiz, the unit's manager of patient care.

“Staff, if you were to speak to them and ask them, have they had experiences with patients who have passed away ... many of them would say very rarely, and now that's become commonplace here,” she said.

In December alone, 212 Manitobans have died of COVID-19 so far — that’s 40 per cent of the 523 people who’ve lost their lives from their virus.

“The number of patients that we're sending up to MICU [medical intensive care unit], the number of deaths that we are encountering, is far greater than we've experienced as surgical nurses.”

Papiz said that staff are working through their fears, putting in long hours and overtime. They’re skipping their breaks to tend to the patients entrusted to their care.

Surgical nurse Aaron Turner said his colleagues are brushing up on skills they haven’t practised since university.

“There was a lot of anxiety from staff, pushing ourselves well out of our comfort zone,” he said.

One of his new duties, he said, is connecting dying patients by phone with their loved ones, who are barred from entering the hospital.

“It’s not something we’ve had to do before,” Turner said. “It becomes part of business, I suppose, but you can never get used to that.”

Despite these new duties, health officials put up for interviews exude a confidence that the employees they have in place — reassigned and otherwise — can handle the influx of COVID-positive cases.

Hospital resources were stretched so thin in early November, the province imposed a near-lockdown to try to slow admissions.

But officials do openly question whether the health-care system can handle the numbers they're seeing much longer.

“They are working overtime,” Cumpsty said of the staff. “They are stretched beyond right now.”

WATCH | 'Every spare space' turned into a COVID-19 unit:

Dr. Edward Buchel, Health Sciences Centre's head of surgery, says the effects of the pandemic are visible every day on the floor of his hospital.

That stretching has included a change, from one-to-one nursing care before the pandemic, to a “team-based” staffing approach, where one nurse cares for multiple patients, with support ranging from respiratory therapists to physiotherapists.

Not everybody on the front lines believes the new care model, announced in November, is tenable.

“Patients will almost surely die in this environment,” a group of nurses at HSC’s medical ICU wrote in an email to officials. “Patients are already suffering from neglect."

The emails surfaced this week, after they were obtained by the Opposition Manitoba NDP.

In another message, staff said they cannot be expected to monitor several isolated patients at once.

They questioned the unimaginable decision that may arise if a nurse is left alone with multiple patients when a colleague goes on break.

“What room should they prioritize to go first if both alarms require their immediate attention for it’s a matter of life and death?” the email asks.

“Please don’t place these tough decisions on their shoulders.”

Everyone's a suspected case

The COVID-19 test swab is the new price of admission to any of HSC’s wards.

Before a patient is admitted anywhere, they receive a rapid test for the virus. It prolongs the visits of patients arriving at the emergency room, who then wait several hours, sometimes overnight, for a result. There can be 16 to 27 patients waiting in the ER at a time.

“We are experiencing increased lengths of stay for transfers," said Chad Chapman, acting director of adult emergency at HSC.

The patients wait in an area of HSC where they're triaged before being sent to another ward, separated from one another by plastic barriers.

Staff approach many of the patients in full personal protective equipment, says Dr. Shelly Zubert, assistant director of the HSC emergency department.

“With the community spread and the positivity rate in our community, we have to assume a lot of those patients coming in have COVID exposures,” she said.

“That creates a huge amount of extra workload, risk to the … health-care workers.”

If they have the virus, a patient may linger in a bed for weeks, complicating the endless push to free up beds for other sick people, Zubert said.

The influx in patients is also overwhelming the laboratory, where professionals in white lab coats are briskly processing rapid COVID-19 tests from patients and staff, from early in the morning to late at night.

The test samples are run through a thermocycler that breaks apart the sample to determine whether the virus is present.

“The COVID-19 samples coming in essentially double our normal daily volume of testing,” said Dr. Heather Adam, a clinical microbiologist.

Surgeries on hold

The lab stands in stark contrast to many surgical wards, which are eerily quiet by comparison. Those wards still have the stretchers deployed and the surgical lights hanging above, but not a procedure underway.

Thousands of elective surgeries, including 6,000 procedures from the spring, have been cancelled, said Dr. Edward Buchel, HSC’s head of surgery, as staff are redeployed elsewhere in the hospital.

“It is important that everybody understands that disproportional effect,” said Buchel, seated on an operating table which is serving no other purpose.

“One extra person with COVID shuts down an operating room. Five patients per day don’t get surgery because of it.”

It’s the “quality of life" surgeries that are being shelved, as he puts it — the procedures necessary after tearing your hip, or blowing out your ACL, for example.

People are suffering, he says.

“Healthy people, my kids, my cohort that is around [my age] feel that if they get COVID, they're probably not going to get terribly sick. That's true, they’ll probably not,” he said.

“But you never know when you're going to slip and fall and tear something in your shoulder or your knee, and you can't access the health-care system now for quality of life surgeries.”

Buchel hopes that message isn’t lost as Manitobans are urged to sacrifice their social gatherings for the greater good — and hopes in spite of those who try to downplay the pandemic, everyone will understand just how real it is.

“We have full floors. We have full ICUs. You've just toured around our hospital that has taken burn units and stepdown units and every spare space we have to be COVID units for sick patients — patients who are going to die without that care.

“Fake news? I don’t know,” he said. “You guys just filmed it.”

WATCH | Inside the medical intensive care unit at Winnipeg's Health Sciences Centre:

Winnipeg's Health Sciences Centre offered a glimpse inside its fight against COVID-19. See how an already-full hospital copes with sick patients who keep on coming.