November 25, 2020

On its 280-kilometre meander south to Lake Erie, the Grand River flows beneath a barricaded bridge along a bypass built to reroute highway traffic around Caledonia, Ont., a bedroom community in southwestern Ontario.

For the past month, its three main routes south have all been blocked by concrete barriers, gravel and trenches dug into the pavement by members of the Haudenosaunee nation re-seizing a portion of land that once ran from the headwaters to the mouth of this river.

Meanwhile, Argyle Street South, which runs through Caledonia’s downtown, is barred by a crushed school bus and junked cars laid across dug-up pavement up from a Canadian Tire and next to a Baptist church.

The bus was taken from the church’s parking lot and the building's sign, which announces worship at 10:30 a.m., is now spray-painted with "Land Back" on one side, "1492" on the other.

This is the front line of a land battle older than Canada — one that has been waged by Six Nations of the Grand River through parliamentary committees, federal land claim processes, the courts and now, again, on the streets of Caledonia.

Six Nations of the Grand River has the largest population of any First Nation in Canada, with about 12,892 members living on-reserve and 14,667 living off-reserve, according to the band's 2019 numbers. Six Nations is mainly composed of the Mohawk, Oneida, Cayugo, Seneca, Onondaga and Tuscarora nations, members of what is also known as the Iroquois Confederacy. (Members of other nations, like the Lenape, also known as the Delaware, are also part of the community.)

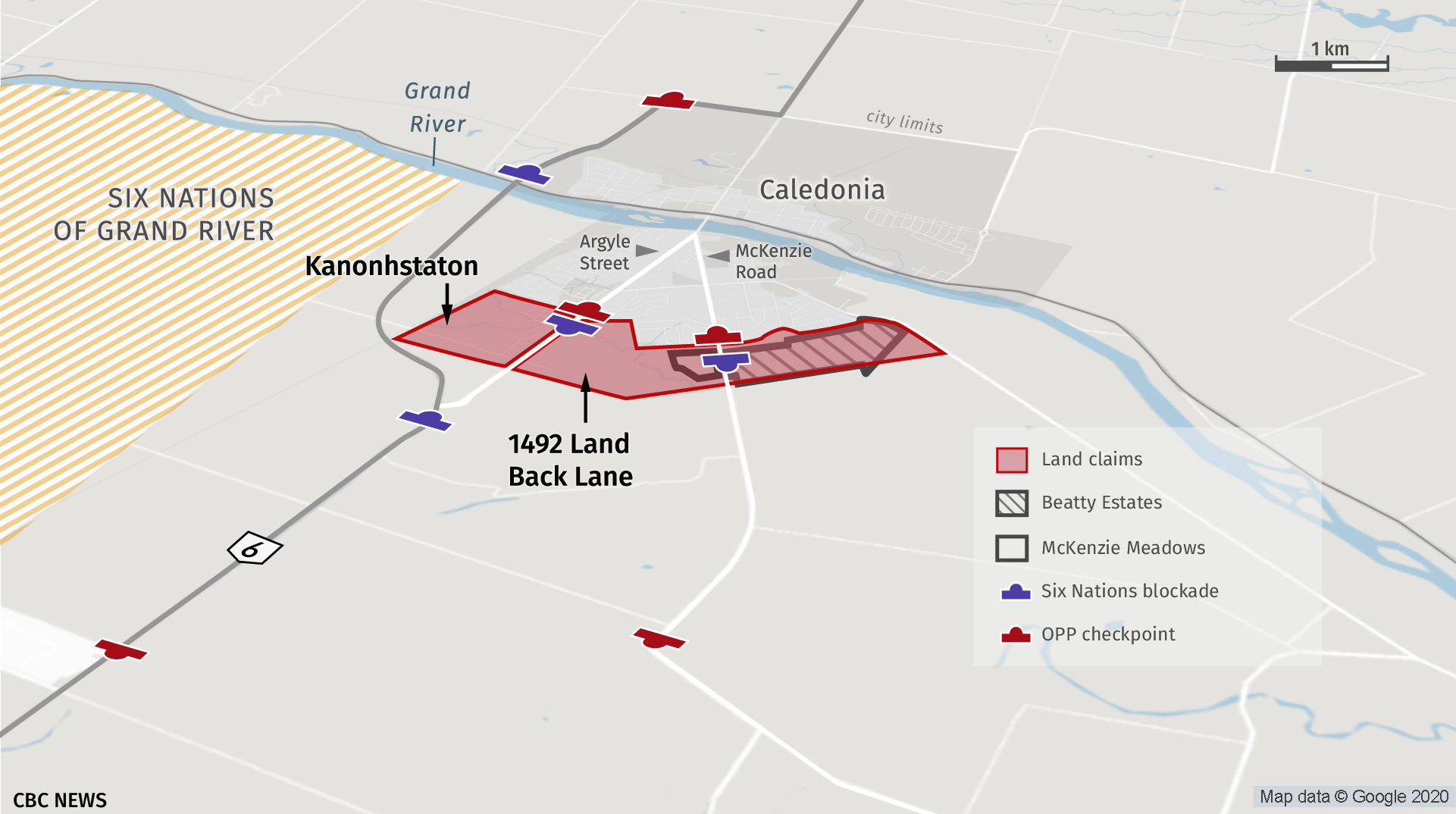

An occupation by Six Nations members in July upended two planned housing projects and has reshaped the view of Caledonia's south end from the windows of the A&W and Tim Hortons as well as the backyard decks of homes along the suburban neatness of Fuller Drive.

Opinions on the fallout of this action vary depending on who you talk to in the two neighbouring communities that grew around the banks of the Grand River. One thing most agree on, from Caledonia residents living along Fuller Drive to those with homes behind the barricades, from the mayor to the main Six Nations protagonists — the root blame lies at the feet of successive federal governments.

Politicians and administrators going back to before Confederation "have looked for every crack in our community to drive wedges, to divide us," said Skyler Williams, the 38-year-old ironworker who has become the face of this Six Nations "land back" movement.

Williams said this while sitting on a concrete block, the crushed hull of the school bus behind him. He was in his trademark ballcap, wearing a camouflage jacket over a black hoodie with a logo, pierced by two crossing arrows, with the words "1492 Land Back Lane."

"I don't know if it takes the blood of myself or my brothers to be on this road for [the government] to take this seriously."

Inside a former one-room Onondaga language school, there's a to-do list along with names of people arrested and those still wanted by the Ontario Provincial Police for their role in the four-month-long campaign to reclaim lands lost 176 years ago and now part of Caledonia.

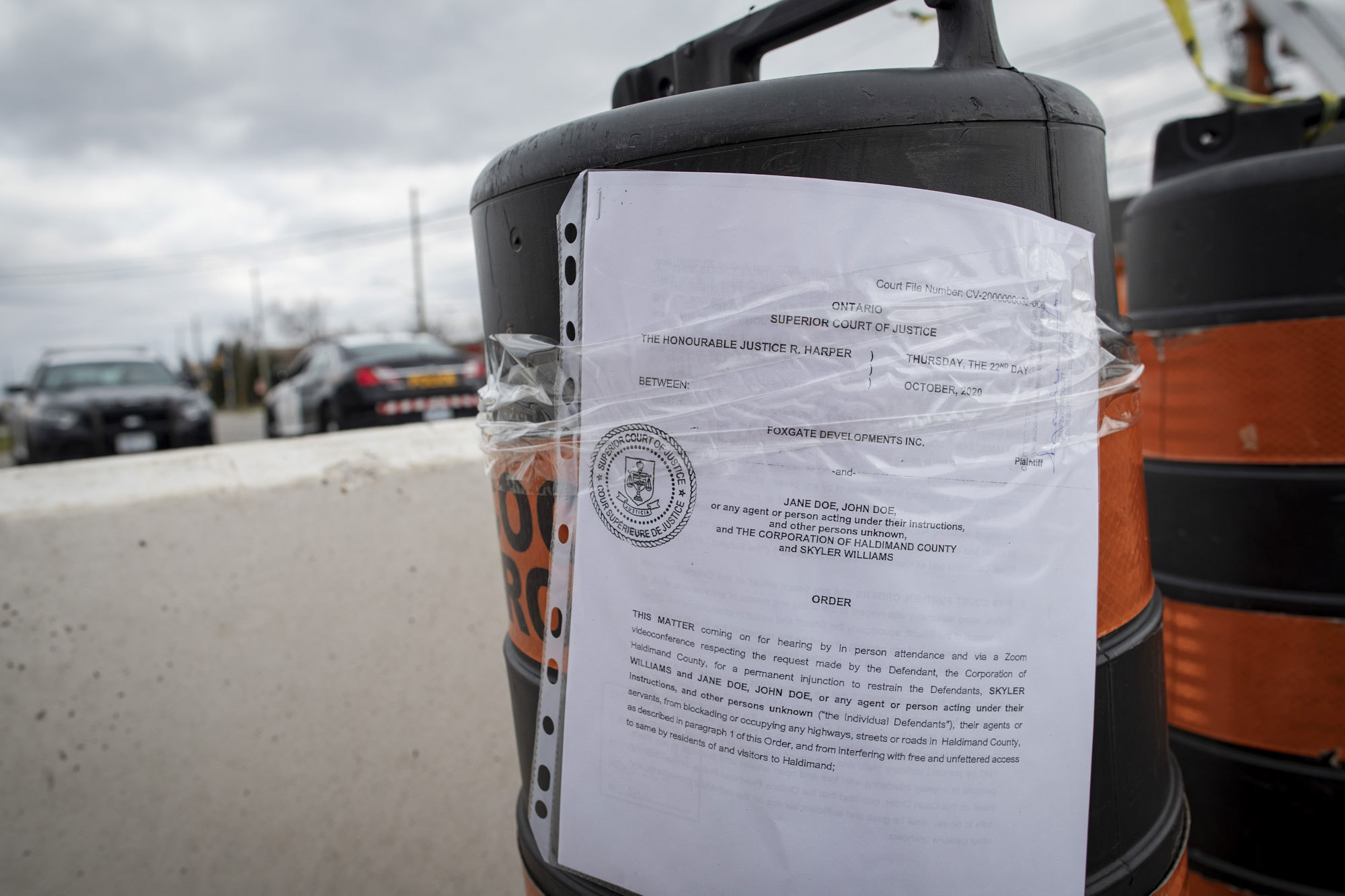

Skyler Williams is one of the wanted — by the OPP for arrest and by Foxgate Developments for $20 million. He's also on the hook for a court order to pay $168,000 in legal bills spent on injunction hearings by Foxgate and Haldimand County, the municipality that oversees Caledonia.

These issues are debated here in the legal war room of 1492 Land Back Lane on the Six Nations reserve. Through an occupation, trenches and barricades, this land reclamation movement has blocked construction of 918 houses in two separate projects along the last undeveloped corridor within the southern boundary of Caledonia.

To one side of the room is a frequently occupied air mattress. In the centre, a long table with coffee cups and paper — lots of paper, including two historical record summaries, one titled the Amalgamated Hamilton-Port Dover Plank Road Lots, Seneca and Oneida Townships and the other, Oneida Township Claim.

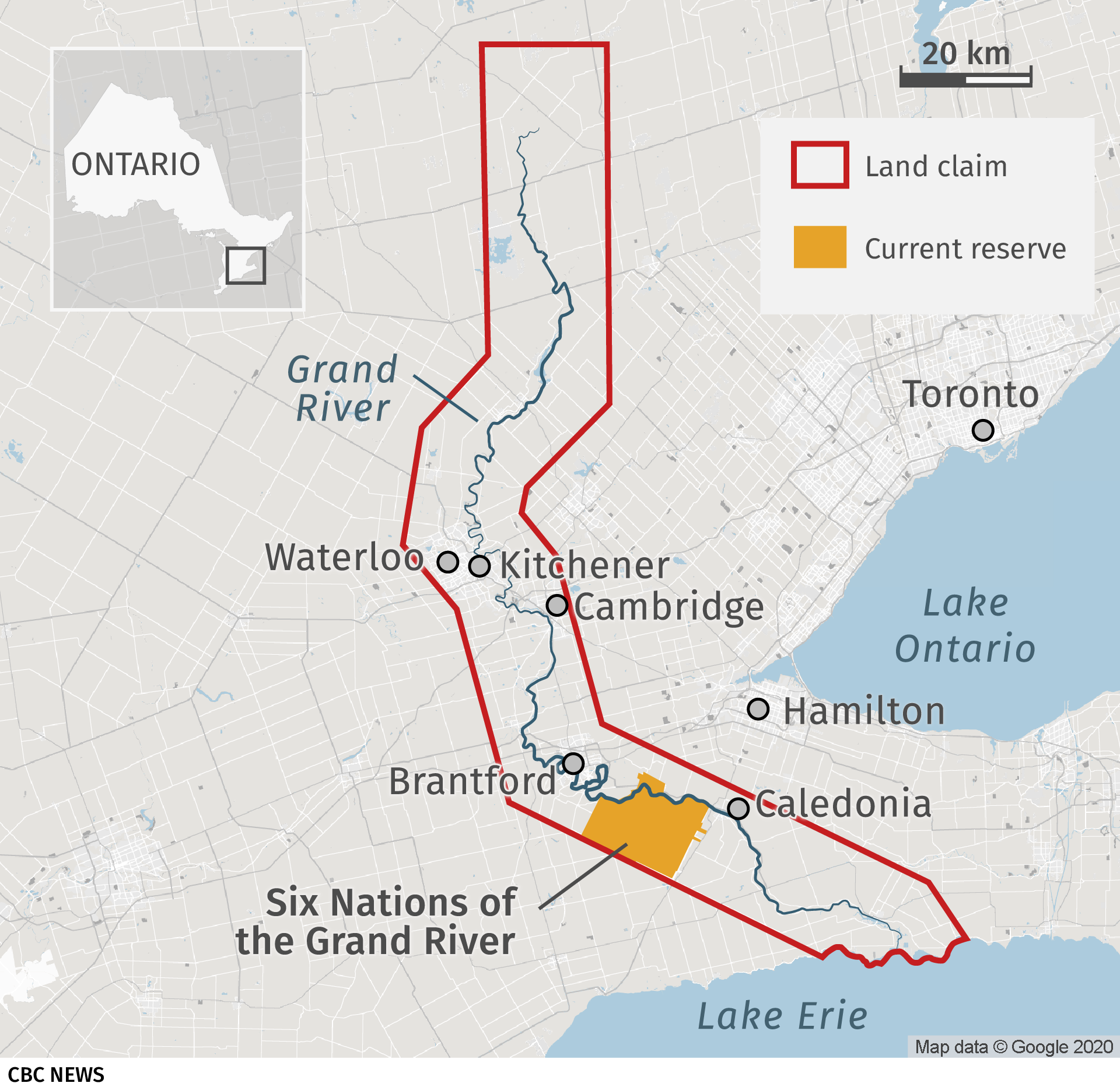

These documents outline the trajectory of loss — namely, that 95 per cent of lands originally granted to Six Nations in the late 18th century have either flooded, been turned into private plots and farms or absorbed by more than two dozen municipalities, including Waterloo, Kitchener, Cambridge, Brantford and Dunnville.

Six Nations did agree to some sales and 999-year leases of areas in the upper parts of their granted lands. However, the documents home in on a messy period in the mid-1800s when settlers and squatters spread through the region, leading to canal projects, contested land sales and surrenders that fed the growth of Caledonia, often at the expense of remaining Six Nations lands.

Six Nations members say the historical record shows the land was stolen through suspect land surrenders brokered between 1841 and 1844 by colonial Indian Department officials who exploited divisions within the Haudenosaunee community with an eye to appeasing squatters and settlers swarming the region.

In mid-July, a group of Six Nations members travelled east from the reserve and set up camp on a planned 218-unit housing development called McKenzie Meadows, renaming it 1492 Land Back Lane. There are now plans to extend that presence on farm lands directly across the road, the site for a 700-unit housing development called Beattie Estates.

Despite several court orders, including a permanent injunction on Oct. 22, 1492 Land Back Lane remains, with no plans to give the lands back.

Using a backhoe, bulldozer and excavators commandeered from a worksite, Six Nations members dug trenches into pavement and barricades now block all road access to the camp.

There is a deep trench on McKenzie Road, along the front entrance of McKenzie Meadows. McKenzie Road runs roughly parallel to Argyle Street South, now blocked at its southern links to Hwy 6 and the Caledonia bypass, which crosses the Grand River, a waterway cutting through the heart of this region and its history.

Add the OPP's buffer checkpoints, and the barricades have shut down more than 15 kilometres of road.

One recent evening in the war room, Skyler Williams's 31-year-old wife, Kahsenniyo, recited, on request, a few lines from one of her poems:

Sometimes all I think about is being able to love you without the weight of our land being stolen.

And I want so badly to wrap my arms around you and melt into each other without fear of agents knocking on our door.

I wish I had something more than this rage to give you.

Skyler sat next to her and swallowed a ball of emotion in his throat as he tried to describe her poetry. "It just grabs onto your soul," he said.

From the beginning, Skyler has been the spokesperson of this movement ― quoted in media reports about the police raid, tire fires and blockade on Aug. 5, and then again after Oct. 22, when tires and pallets burned and the barricade perimeter was established.

Although Skyler has been identified as the face of 1492 Land Back Lane, Kahsenniyo said there is no leader in the movement, which is run by a collective. She said Skyler was chosen by a group of women in the organization to be the face, so the others could remain faceless and nameless.

Who are the women?

"The women," Kahsenniyo said, with no further explanation.

Skyler understands the threat of jail time is real for his high-profile role in all this. He has spent time behind bars before — seven months in pre-trial custody — on charges stemming from a similar Six Nations land occupation in 2006. He said he spent four months of it in solitary confinement, the result of friction with a guard, and read case law and the Bible twice. The charges were eventually dropped.

Skyler and Kahsenniyo Williams have been together for 10 years and the life they've built is now on the line for "land back." Kahsenniyo said she is clear-eyed about what could come and the risk to their blended family of four daughters. They constructed a home mainly from recycled materials, like timber from an old barn. Called the Earthship, it is powered by solar energy and uses water collected from rain and melted snow.

"I know that there is going to come a time that things are going to be really hard. In criminal court, as well as civil court, it's going to be exhausting and scary and all of those things," she said.

"It's easy to get lost in that, it's easy to forget that there will come a time that is past that...The sacrifice is huge."

Theirs is a generation that came of age against the backdrop of land struggle. For Kahsenniyo, it was 2006 and the Six Nations land reclamation battle over a housing development called Douglas Creek Estates. It was also when Kahsenniyo said she first fell in love with Skyler, watching him split wood and helping "little old ladies."

For Skyler, the turning point was in 1995, during the occupation of Ipperwash Provincial Park by members of the Chippewas of Kettle and Stoney Point First Nation over the expropriation of their land during the Second World War. He arrived the day after the OPP shooting of Dudley George.

Now, the couple stand on the front lines of their own movement.

The fate of four projects in Caledonia's south end ― two housing developments and two connected road projects ― now depend on the outcome of events around 1492 Land Back Lane.

Haldimand County Mayor Ken Hewitt said the subject lands were added to Caledonia's urban boundary in the 1980s.

Foxgate Development and Wildwood Developments, which are behind McKenzie Meadows and Beattie Estates, respectively, both purchased the lands legally, Hewitt said.

Foxgate pre-sold 218 homes for McKenzie Meadows, but the project is now at "risk" and the occupation and barricades are proving "fatal" for some of the home buyers and 67 involved contractors, according to statements sent to CBC News by Losani Homes and Ballantry Homes, who are partnering on the project.

Losani provided several anonymous statements it said were from homebuyers who expressed bewilderment, anger, fear and regret over the events upending their life plans.

"We are hopeful that the OPP will proceed with the injunction so that we can proceed with the project," said the statement from Losani.

Ballantry Homes said it won't issue pre-sales for homes on Beattie Estates.

Hewitt said that the land reclamation has "an economic cost, there is a psychological cost, there is a reputational cost and all those costs aren't easy to quantify."

Hewitt, who made a downpayment on a house in McKenzie Meadows for his son, who is graduating from university, said the county's insurance won't cover the roughly $500,000 in damages created by barricades and trenches on the roads. Hewitt said the bill would be sent to the province.

Hewitt said Ontario should take a firm stand on what he sees as the theft of lands by Six Nations members.

"The province has a role to play, and a responsibility to step up and stand behind their land titles, and it needs to be very clear," said Hewitt.

The Six Nations Elected Council signed a deal in 2019 with the developers for $352,000 and 17 hectares of land in exchange for support of the two housing projects. However, Six Nations' traditional government, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy Council of Chiefs, supports 1492 Land Back Lane.

This difference in posture can be traced back to 1924, when Canada used the RCMP to execute a coup, replacing the traditional Haudenosaunee government with an elected council, creating a schism in Six Nations that persists today.

The two governments are now working together again for possible negotiations with the federal and provincial government. Ottawa and Ontario say they are ready for talks.

Hewitt and the developers say arguments over the status of the lands were decided long ago. In fact, the struggle over this history remains unresolved.

WATCH | Six Nations members expand blockades around land reclamation camp:

IV.

A river runs through this story ― the Grand River. About 10 km on each side — from its source near the town of Dundalk all the way down to Lake Erie — was granted to Six Nations in 1784 for allying with the British during the American Revolution. But a proclamation by British officer Sir Frederick Haldimand, viewed as a treaty by Six Nations, began to crumble shortly after its inception.

In 1792, 11,288 hectares around the river's headwaters were severed from the grant after British bureaucrats realized the land wasn't part of what was originally surrendered by the Mississauga Nation, which underwrote the Haldimand Tract.

The British never returned the lands — which are part of Six Nations' reparation claim — even after they were surrendered, the first cracks of a fault line that eventually gave way to the pressure of history, releasing shockwaves still roiling the landscape.

The Grand River cleaves Caledonia, and its main street, Argyle, into north and south. Argyle Street was once Highway 6, before the 1982 construction of the Caledonia bypass to divert Highway 6 traffic around the community. Highway 6 was previously called the Port Dover-Hamilton Plank Road, which was completed in 1843.

The construction of the road helped spur the growth of Caledonia but also the sale of Six Nations lands. Six Nations maintains colonial authorities illegally sold land on either side of the road when their leadership only agreed to leases. It remains an outstanding claim.

The battle to regain a portion of lost lands south of the Grand River has been waged over Argyle Street South and its intersection with 6th Line, a two-lane country road that runs a kilometre west before hitting the Six Nations reserve boundary.

This was the location of the inciting incident for the current standoff. Before sunset on Oct. 22, OPP officers fired a rubber bullet and an electroshock weapon at Six Nations members who confronted them with rocks and lacrosse sticks. Running skirmishes to control this intersection exploded with burning tires and pallets, evolving into the co-ordinated operation to seal off road access to 1492 Land Back Lane.

The intersection frames the southeastern corner of land called Kanonhstaton, which faces the back entrance to 1492 Land Back Lane.

Kanonhstaton was once a planned housing development called Douglas Creek Estates. In February 2006, a group of Six Nations women reclaimed the property that sat next to the Baptist church on Argyle Street South.

Events detonated on April 20, 2006, after the OPP raided the site. The community reacted and hundreds stormed the site, pushing the OPP back. Tires, a vehicle and a bridge burned.

This triggered months of on-and-off-again blockades and violent clashes between Six Nations members and Caledonia residents, which went on for a time after Ontario bought the property in June 2006. The land remains in Ontario's hands but continues to be occupied by Six Nations members.

Without the taking of Kanonhstaton, there would be no 1492 Land Back Lane. The 2006 battle not only set an example for a successful land reclamation, it now serves as a beachhead for further re-conquest of lands.

Kanonhstaton creates a protected corridor from Six Nations, down 6th Line, all the way through Caledonia's undeveloped lands within its southern boundary.

Donna Silversmith, from the Cayuga Snipe clan, spends her days on Kanonhstaton at a bustling support camp for 1492 Land Back Lane. She ensures there is enough refreshment ― pizza, corn soup, strawberry juice ― for those on the front lines patrolling the barricades.

Six Nations members often stop by to say hello, drop off supplies and sit around a barrel fire, where you'll hear Haudenosaunee drumming and singing amid the woodsmoke.

"Usually, we women are right there on the front line with our men, because we have that rational voice, that rational stance we take, so things don't get out of hand," she said.

While things remain at a stalemate between the OPP and the barricades, the threat of a police raid keeps tensions here running like a low-frequency hum.

Silversmith said Six Nations children who lived through the Douglas Creek Estates fight are now on the front lines of 1492 Land Back Lane.

"Now we are seeing that pattern," she said. "It's generational now; we are trying to break that cycle."

Hector MacDonald lived amid the turmoil of 2006. Retired and in his 60s, he is one of a handful of non-Six Nations residents whose homes sit on 6th Line, between barricaded Argyle Street South and the reserve boundary.

"This time, it's more radical," said MacDonald.

Because of the barricades, MacDonald said he no longer has access to a responsive 911 service, which is administered by Haldimand County.

"We're in limbo here," said MacDonald. "It's a very touchy situation."

Dan Roberts, a 45-year-old safety compliance officer for a trucking company in Guelph, Ont., lives in a neighbourhood tucked behind a Canadian Tire a couple of streets over from the old Douglas Creek Estates site. He, too, watched as his neighbourhood became a conflict zone in 2006.

Roberts was at work on Oct. 22 of this year when he received a text from his daughter warning him to be careful on the drive home because things were flaring up along the Hwy 6 Caledonia bypass.

Frustration is rising again, he said.

"My fear is the irreparable damage this is going to do to our town and to the relationship with Six Nations," said Roberts.

He said the barricades and trenches had done more than just reshape Caledonia's roads and force drivers to make half-hour-long detours. These barriers have also blocked progress on finding common ground between the two communities, he said.

"If you want us to understand where you are coming from," he said, addressing Six Nations protesters, "don't try to bully us… We may not agree on what each other believes and understands as part of the past, but we have to respect each other."

The morning after the night of flaming tires and barricades on Oct. 22, Tracy Bomberry came in from her home in Six Nations. A mother of three boys, two of whom still attend high school, she dropped one son off at school in Caledonia's southern end and drove about 900 metres to where police cruisers blocked Argyle Street South near the Canadian Tire.

Bomberry, 51, arrived to witness OPP officers arresting a 24-year-old Six Nations man involved with 1492 Land Back Lane who was suffering a mental health crisis.

While filming the arrest, Bomberry captured the off-camera voices of two men standing to the side shouting at the OPP officers to "take him down, boys, come on."

She focused her lens on the two men.

"It's a beautiful day, too," said one of them, a heavy-set man.

"It's a good day to go and burn some f—king longhouses," said the other, lankier man, wearing a Toronto FC hoodie, referring to the traditional living and meeting structure of the Haudenosaunee.

The scene sent Bomberry back 14 years.

"It wasn't surprising to hear stuff like that. I've heard that before, during 2006," said Bomberry, who works as an outreach and event coordinator for Indigenous student services at McMaster University.

"It's just right there below the surface — the racism."

Crossing Argyle Street South west to east from 6th Line, a rutted, muddy but maintained back road snakes through bushes and high-voltage transmission towers until it opens to an area levelled and gridded by the skeletons of planned streets and plots for the McKenzie Meadows subdivision.

It's now dotted with clusters of tents, at least two insulated wooden structures, an outhouse and a makeshift kitchen next to a fire pit.

One of the residents is Jace Wasgahegan, 23, who traded his home in Kitigan Zibi, a Quebec Algonquin First Nation 670 kilometres away, for the spartan life of a tent, baby wipes and dry shampoo on the front lines of the occupation.

Back in September, Wasgahegan helped organize road blockades and checkpoints near his own community aimed at halting the Quebec moose hunt on Algonquin territory. Then, he felt the draw of another struggle.

"This is definitely my calling," he said. "So many of us are just tired knowing, full stop, that we can't go with the way things are.... Whatever happens to me was meant to happen."

In the past, Six Nations have blocked roads in support of other communities involved in similar land struggles. Now, Six Nations is seeing this solidarity repaid.

Behind Waskahegan, a shipping container was blasted with coloured graffiti declaring, "Solidarity Across Turtle Island." The container sits on soil known as Oneida Township, an area south of the Grand River that Six Nations maintains was destined to become part of their reserve lands.

However, colonial authorities claimed the land had been surrendered in 1844, based on 45 signatures purportedly belonging to the Six Nations chiefs. Historians remain divided over the validity of this surrender, who actually signed it and whether colonial authorities used pressure and divisions within the community to induce their desired result.

The matter could still take decades to resolve, after a 1995 lawsuit filed by Six Nations was reinitiated following a breakdown in talks with Ottawa and Ontario in 2009.

The lawsuit seeks reparations and compensation ― ranging from the billions to the trillions of dollars, depending on interest rates ― for lands and Six Nations trust fund monies lost and squandered by colonial authorities.

Money from the surrender and sale of Six Nations lands, as well as timber revenues, were held in trust by the colonial administration, which spent the funds ― often without the knowledge of Six Nations ― on public and war debt, along with infrastructure projects.

For example, one financially disastrous project to build a canal on the Grand River between the late 1830s and early 1840s completely drained Six Nations funds, leading to famine and death among the Haudenosaunee.

"It's a real exercise in frustration to try to settle this unfinished business of long ago," said William Montour, who was elected chief of Six Nations from 1985 to 1991 and 2007 to 2014.

Montour said First Nations leadership warned Ottawa in the 1980s that the next generation would not have the same patience to wait decades for settlements through the courts or cumbersome federal land claim policies.

Their demands for reparations would be more forceful and immediate, he said.

"Until that's settled," said Montour, "there is not going to be rest."