September 1, 2016

The story was originally published in 2013 as "The Agony of Rob Ford." It has been updated since his death on March 23.

Ford Nation

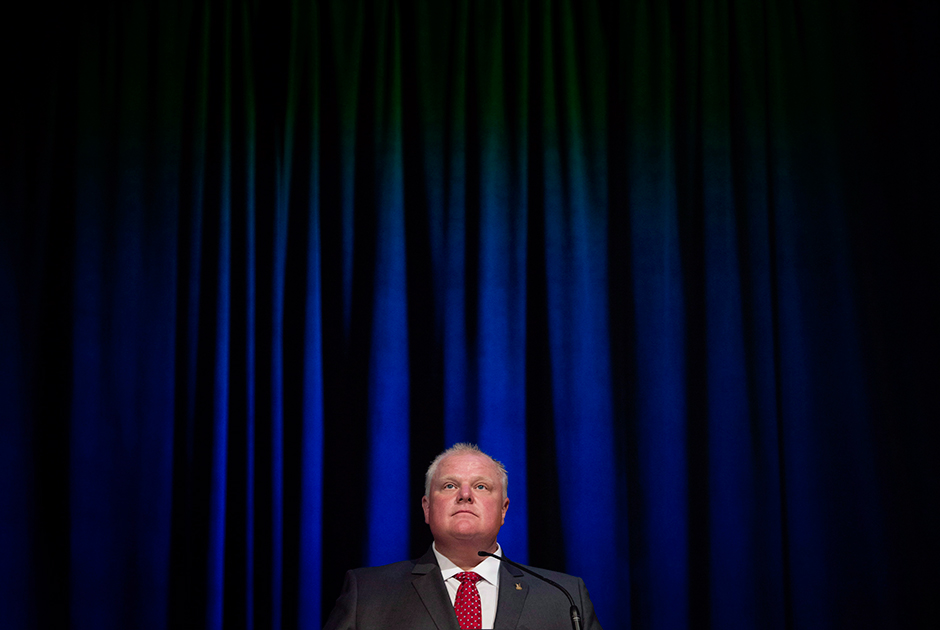

If Rob Ford had one defining trait, it was his bluntness.

To his supporters, it was a mark of his honesty and authenticity. To his critics, it symbolized his impetuousness and lack of polish.

Either way, it was his candour and disdain of political platitudes that carried Ford from Toronto-area businessman to candid, often cantankerous city councillor to mayor of the biggest municipality in Canada.

As councillor for Ward 2 Etobicoke North, a suburb in Toronto’s west end, in the early 2000s, Ford developed a reputation for accessibility. Potholes, parking, policing — whatever your issue as a constituent, he endeavoured to return every phone call personally, even going so far as to give out his home number.

Ford also styled himself as a model of fiscal responsibility. He routinely decried the spending at city hall and trumpeted his own thrift – where some councillors logged $50,000 in yearly office expenses, Ford spent just $2.

“Hell will freeze over before I will spend taxpayers' money out of my office budget to support myself and my own enhancement in society,” he once said.

Ford’s dogged commitment to cost-cutting endeared him to many voters.

It helped that the Ford family’s business, DECO Labels & Tags, enjoyed annual sales in the neighbourhood of $100 million, according to the Toronto Star. Yet despite his personal wealth, Ford set himself up as a champion of Joe and Jane Average, lobbying on conservative principles of low taxes and smaller, less intrusive government.

He often did so in a belligerent way.

Reporters who covered Toronto city hall during the 2000s recall a number of occasions when Ford personally insulted fellow councillors. He called one colleague “a slithering snake;” another “a waste of skin.”

Despite his lack of verbal restraint, Ford’s crusade against the city hall establishment and dogged commitment to cost-cutting endeared him to many voters.

During his winning run for mayor in 2003, David Miller made a sweeping appeal to Torontonians’ civic pride. Seven years later, Rob Ford effectively rattled their wallets as a reminder of what the Miller years had cost them.

Ford always prided himself on being a straight talker, and his 2010 run for mayor surely stands as one of the most unequivocal political campaigns in recent Canadian history.

He cast city hall as a den of unchecked spending, emphasizing the fact that during Miller’s seven-year stint, city expenditures rose by 39 per cent.

Ford’s campaign message was almost comically simple, distilled in two pithy slogans: stopping “the gravy train” at city hall and restoring “respect for taxpayers.”

Two items got Ford especially angry: the $60 vehicle registration tax, a lucrative annual levy on car owners that he saw as emblematic of city hall’s stultifying bureaucracy; and Transit City, an infrastructure plan to expand public transportation through light rail transit (LRT) that was largely supported by left-leaning members of city council.

By the end of election night — Oct. 26, 2010 — it was startlingly clear that Ford had inspired more than just his base. He took 47 per cent of the vote, outpacing the closest candidate, former deputy Ontario premier George Smitherman, by 10 points.

To demonstrate he was a man of his word, within two months of taking office, Ford helped kill the vehicle registration tax and declared that “Transit City is over, ladies and gentlemen.”

Toronto was beginning to look a little like Fortress Ford.

Ford’s election was proof of a large contingent of active, engaged conservative Torontonians who shared his vision and had facilitated his ascension to office — the putative “Ford Nation.”

The emergence of Mayor Ford split city council into opposing political camps: the right, which saw him as a corrective to downtown elitism and profligate spending, and the left, which seemed determined to thwart his every move.

Over the next few years, these divisions would lead to acrimonious debates, and often prolonged stalemates, on issues such as budget cuts, union negotiations, transit, even plastic shopping bags.

There were whispers of a faction called “Ford Nation” during the mayoral campaign, but the phrase acquired greater heft after Ford took office. In March 2011, Ford invoked his base to threaten the Liberal provincial government, under then-Premier Dalton McGuinty, into giving cash-strapped Toronto more money.

“If they choose not to help us,” Ford said, “then I have no other choice but to get out, as I call it, Ford Nation and make sure they’re not re-elected.”

Rob Ford coaching football

If the concept of “Ford Nation” seemed confrontational, it soon became clear that it was also aspirational. Nick Kouvalis, a conservative political strategist who had served as Ford’s campaign manager, was already making noises about fostering a broader right-wing movement across the province — and beyond.

Evidence of that came in the summer of 2011, when Ford hosted a backyard barbeque for prominent conservatives that included federal Finance Minister Jim Flaherty and Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

In a speech that contained a lighthearted allusion to a fishing trip he had taken with Ford, the then-PM thanked the mayor for shoring up conservative votes in the Toronto area during the 2011 federal election, which gave the Tories their sought-after majority.

“Rob is doing something very important that needs to be done here,” said Harper. “He is cleaning up the NDP mess here in Toronto.”

Many would counter that Ford made a mess of his own — one that included political clashes in council, legal investigations and substance abuse while in office.

Ford the renegade

As mayor of Canada’s largest city, Rob Ford was extensively photographed. But one of the most evocative images was an amateur snap taken in the summer of 2012 on the Gardiner Expressway, a busy Toronto thoroughfare near Lake Ontario.

Taken from an adjacent vehicle, the slightly blurry image clearly shows Ford reading briefing notes while driving his Cadillac Escalade SUV.

Perhaps even more startling than the photographic evidence was the response it elicited from Ford. When a reporter asked him whether reading and driving was a recurring habit, he said, “Yeah, probably, yeah. I'm try[ing] to catch up on my work and you know I keep my eyes on the road, but I'm a busy man.”

Toronto police urged the mayor to hire a chauffeur; so did his budget chief, as well as his brother, Coun. Doug Ford. The mayor demurred.

“They offered me a car when I first got elected. And a driver. And that was well over $100,000 combined. I think that’s a waste of taxpayers' money," Ford told a news conference a week later.

The episode symbolized Ford’s outright rejection of orthodoxy — and his stubborn belief that he was always in the right.

For much of his time at city hall, Ford defied the image of the entitled career politician. His refusal to take a chauffeur was very much in line with his refusal to amass office expenses or to accept a security detail – even after his sister’s common-law partner broke into the mayor’s home and threatened his life in early 2012.

The unwavering “respect for the taxpayer” mantra won him many fans as a city councillor and lifted him to the mayor’s seat. But his refusal to budge on deeply held convictions — both political and personal — led to a seemingly unending series of council clashes, legal scrapes and public controversies.

Arguably the most politically combustible issue at Toronto city hall in recent years has been public transportation. Ford’s decision in late 2010 to retire Transit City, a proposal favoured by many left-leaning councillors to increase the Toronto Transit Commission’s light rail (LRT) coverage, was the first step in his attempt to push through his own transit strategy.

For much of his time at city hall, Ford defied the image of the entitled career politician.

One word that Ford liked more than almost any other was “subways.” While LRT lines are cheaper to build, underground transportation was the central plank of Ford’s transit plan. Many councillors repeatedly questioned how the mayor planned to fund the $1-billion outlay required to dig additional subway lines, but Ford was adamant, to the point where he would chant “subways” like a petulant child.

In July 2013, Ford won vindication for his single-minded strategy when Toronto city council voted 28-16 in favour of extending subway service in the east end.

"I truly, truly believe that Toronto can count on the province and the federal governments ... as partners in this historic project," Ford told reporters.

While the transit debate produced some memorable tantrums, Ford’s obstinacy in other political matters produced some notable returns. Thanks to his budget-balancing efforts, city expenditures stopped rising. He eked out a labour deal with the city’s major unions that eliminated jobs-for-life guarantees.

But average citizens are more likely to remember his inflexibility on social matters, like his standing refusal to attend Toronto’s annual gay pride parade — one of the largest in the world and a must-attend event for previous mayors — because it coincided with the Ford family’s annual cottage retreat.

An iconoclast politician can be a bracing thing, but many Torontonians became furious not only with his list of gaffes but his reliance on transparent lies to dodge the blame.

Back in 1999, Ford was charged with driving under the influence and marijuana possession in Florida; when it came up during his 2010 mayoral run, he claimed he had forgotten about the incident and merely failed to give a breathalyzer test.

In 2006, while a councillor, Ford was tossed from a Toronto Maple Leafs game for shouting obscenities at a couple in the stands; Ford responded by saying he wasn’t even there.

A pattern had emerged.

Football and politics

On the subject of honesty, here’s another ill-fated statement.

In the thick of his 2010 mayoral campaign, amid animated talk of tax reform and trimming government spending, Rob Ford made a pledge: If elected, he would cease coaching the football team at Don Bosco Catholic Secondary School.

Although he had been coaching the team in northwest Toronto on a volunteer basis for nearly a decade, Ford conceded that mayoral duties would likely make it impossible to keep up his commitment to student athletics.

Alas, giving up the gridiron proved too much for him.

In fact, on the night after he was elected, Ford cut short an interview with Carol Off, co-host of CBC Radio’s As It Happens, so he could get back to coaching football.

That on-air encounter was more than just awkward radio — it foreshadowed just how much football would come to complicate his role as mayor.

Ford became notorious for leaving council meetings early — or skipping them altogether — in order to make team practices.

But the most troubling episode was a conflict of interest case that nearly cost him his job. In 2010, before he became mayor, council found that Ford had improperly raised $3,150 for his private football charity using city letterhead. When the issue of reimbursement came to a council vote in February 2012, Ford voted against paying the money back, which contravened conflict of interest guidelines. An Ontario judge ordered him removed from office, but Ford won on appeal.

Ford’s football fixation ultimately showed the difficulty of quitting a lifelong love affair. As a youngster, Ford dreamed of a career in professional football, and in the early ‘80s, his father sent him to a summer camp run by the NFL’s Washington Redskins (who won the Super Bowl in 1983). Ford also trained at Indiana’s University of Notre Dame, a storied institution in the realm of U.S. college football.

Ford applied those skills on the field at Scarlett Heights Collegiate, but his fledgling career seemed to stall at Carleton University in Ottawa where, according to a Toronto Life profile, he only played one season. (There’s also some question about the amount of game-time he saw.)

While his own football career may have been dashed, Ford became heavily invested in cultivating young talent, many of them at-risk youth. In 2001, he established the football program at Don Bosco, donating $20,000 to pay for the team's equipment.

"I'm not going to turn my back on these kids."

He also created the Ford Football Foundation, which has raised money from individuals and corporations to fund programs at other Toronto-area schools.

“Many kids have nothing to do after school and for some that could lead to trouble,” Ford told the Toronto Star in 2009. “I have seen it happen and I've noticed a huge difference since we started football at Don Bosco. I'll go to bat for them anytime.”

Seeing those kids respond to the discipline and camaraderie of football was likely one of the reasons Ford found it so difficult to relinquish his coaching duties when he became mayor.

Ford’s time commitments to Don Bosco became an increasing issue, as councillors and media raised concern about the number of council meetings Ford was missing in order to make football practice. (The Toronto Star pointed out that his attendance record was still better than that of his predecessor, David Miller.)

To many observers, the most galling incident came in November 2012. Responding to a police request, the Toronto Transit Commission mobilized two buses — including one full of paying customers — to pick up Don Bosco players after a game at a north Toronto high school ended in a brawl. Ford said the bus dispatch “had nothing to do with me,” but there was evidence that he called TTC CEO Andy Byford personally that afternoon about transportation for his players.

While the controversy surrounding his football obligations intensified, Ford scored vindication in late November when the Don Bosco Eagles fought their way to the regional finals, making their first-ever appearance in the Metro Bowl.

With the city’s beleaguered mayor calling shots on the sidelines, there was considerable media interest in the 2012 championship game. To Ford’s frustration, Don Bosco was the second-best team in the Rogers Centre that night, losing 28-14 to the Huron Heights Warriors. While noticeably upset about the loss, Ford pledged his continuing commitment to the team.

“I’m not going to stop coaching. These kids did fantastic. I’m not going to turn my back on these kids,” he told the Toronto Star.

In late May, however, the Toronto Catholic school board ended Ford’s relationship with Don Bosco when it banned him from coaching at any school in its jurisdiction. It all had to do with an interview Ford gave to Sun TV, in which he had characterized many Don Bosco students as belonging to gangs or coming from broken homes.

During a May 24 press conference, Ford made a point of thanking and congratulating “all the young men that I’ve had the opportunity to coach and improve their lives in the last 10 years at Don Bosco.”

While he was stoic in public, the firing was no doubt an upsetting chapter for this lifelong football fan.

Ford’s drug use

And then, of course, there was the crack saga.

It started back in May 2013, when the Toronto Star and U.S. gossip site Gawker reported that they had seen footage of Ford smoking crack cocaine.

The mysterious party who had recorded the video was offering to sell it for six figures, which prompted Gawker to launch a crowdfunding campaign to buy it.

Ford now had an international profile — for all the wrong reasons.

Torontonians became used to seeing those daily scenes from City Hall of Ford bulldozing through mobs of reporters eager to catch the mayor in a telling moment.

For months and months, Ford alternately dodged and denied the accusations about drug use.

In late October, Toronto Police Chief Bill Blair announced that police had the infamous crack video and that it corroborated what had been reported in the media.

Soon after came the confession heard around the world.

On Nov. 5, 2013, a visibly weary Mayor Ford exited the elevator on his floor at City Hall and was immediately encircled by a throng of journalists. But Ford was taken aback when one reporter asked him why it seemed that his brother, Coun. Doug Ford, was doing most of the talking when it came to the mayor's alleged use of crack cocaine.

"Yes, I have smoked crack cocaine."

After an awkward initial exchange with reporters, Rob Ford made a startling admission:

"Yes, I have smoked crack cocaine."

The news immediately went viral — it lit up Twitter, made the front pages of CNN, BBC and the New York Times and garnered stories as far afield as Germany and China. (It also inspired a Taiwanese animation video, featuring an underwear-clad Ford with an entourage of beavers — as sure a sign as any nowadays that a scandal has gone global.)

The fact that a big-city mayor was admitting to drug use was of course newsworthy, but what made the statement so stunning was that Toronto's chief magistrate had spent half a year vigorously denying that he had smoked crack — often suggesting that the accusations were the product of a media smear campaign.

But even before the crack allegations emerged in May 2013, there were intimations that the mayor had a substance abuse problem.

There was the time in 2006 when he was escorted from a Leafs game after shouting obscenities at a couple seated nearby. Ford later apologized, saying he had had too much to drink.

Then there was the St. Patrick's Day incident. According to an email written by city hall security staff on duty on March 17, 2012, Ford was at City Hall at 2 a.m. that night and "it was quite evident the mayor was very intoxicated" and was seen headed to the security desk "with a half-empty bottle of St-Remy French brandy."

In February 2013, the Toronto Star reported that Ford had been asked to leave the Garrison Ball, a charity dinner for Canadian Armed Forces personnel, after he was seen speaking in a "rambling, incoherent manner" and upsetting other partygoers.

"I was elected to do a job and that's exactly what I'm going to continue doing."

The next month, former mayoral candidate Sarah Thomson claimed the mayor groped her at a party for the Canadian Jewish Political Affairs Committee, adding that she had "never seen him so out of it." Ford said the claims were "completely false." Mark Towhey, his chief of staff, said the mayor had only drunk water that night.

In August, Ford was caught on video at the Taste of the Danforth festival behaving erratically. One witness told the CBC "he was not himself — he was drunk." Doug Ford later told the media, "He had a couple of pops, big deal, no one got hurt, everyone had a good time."

While he was deflecting accusations about crack and alcohol use, Rob Ford did own up to having used marijuana, telling reporters after a luncheon event that month that he’d "smoked a lot of it."

After the incident on the Danforth, Coun. Jaye Robinson said Ford needed to "take a leave of absence, address his personal problems and then come back to continue to act as the mayor of Toronto."

Robinson was hardly a voice in the wilderness. Other councillors, as well as newspaper columnists, had been advising for months that Ford take a break to work through his substance issues. In response, the mayor exhibited his usual bullish defiance, saying the reports were exaggerated and that they had no bearing on his ability to run the city.

Ford's rhetoric softened in early November. On his weekly radio show, Ford apologized for his behaviour on several occasions, including getting "hammered" at the Taste of the Danforth and letting things get "a little out of control" on St. Patrick's Day 2012.

Many councillors and political watchers thought it only amounted to a partial apology. But Ford came clean on Nov. 5.

After the seemingly impromptu crack confession outside his office, Ford held a news conference later in the day in which he expressed his shame at having smoked crack and told Torontonians he was "sincerely, sincerely, sincerely sorry."

But regarding his fitness to remain mayor, he was clear: "I was elected to do a job and that's exactly what I'm going to continue doing."

Reflecting a growing concern about Ford's health and well-being, Coun. Denzel Minnan-Wong said the province should step in to remove the mayor from his post.

"We have told him that he needs to find the exit. He doesn't seem to be listening," Minnan-Wong said. "So if he can't find the exit, I think we have to show him the door."

At his Nov. 5 news conference, Ford pledged that he had "nothing left to hide." That proved to be an idle guarantee. Two days later, the Toronto Star released another video. Shot in an undisclosed location, the clip showed the mayor in a highly excitable mood, uttering curses about an unspecified fight.

"I had become my own worst enemy."

When reporters asked him about it, all that Ford could offer was that he was "extremely, extremely inebriated" at the time — without specifying the offending substance — and the caveat that "I hope none of you have ever, or will ever, be in that state."

It was undoubtedly one of the most explosive, jaw-dropping weeks ever at Toronto City Hall, and the numerous revelations provided tantalizing fodder for worldwide news media and late-night talk show hosts.

But amid the gleeful mockery, there was a growing sense of sympathy for a mayor who was obviously struggling with various substances.

Daily Show host Jon Stewart, ordinarily over-the-top satirical about Ford's exploits, sounded a cautionary note: "Mayor Ford's a lot of fun to ridicule, but my guess is, not a lot of fun to eulogize."

Many more months of public shaming ensued before Ford finally checked himself into the GreeneStone rehab clinic in Bala, Ont., in May 2014.

When he emerged the next month, he held a press conference, saying he had been in "complete denial" about his struggle with drugs and alcohol and the toll it was taking on his life.

Said Ford, "I had become my own worst enemy.”

Family matters

Ford was the author of many of the most scandalous episodes of his career. But various family members contributed controversies of their own.

Anyone seeking public office will tout the importance of family — it implies trustworthiness, psychological solidity and an appreciation of traditional values. But political dynasties such as the Kennedys and the Clintons have demonstrated that some family members have the potential to become political liabilities — a prospect that dogged Rob Ford long before he became mayor.

His sister, Kathy, for example, has had links to drug dealers and has been in the middle of a number of bizarre and violent incidents.

But one of the most damaging stories, however, concerned Rob’s brother Doug.

On May 25, 2013, the Globe and Mail published a cover story — quoting several anonymous sources and based on 18 months of reporting — that alleged Doug Ford sold hashish in Etobicoke in the 1980s.

In response to the article, Doug Ford spoke to several media outlets, utterly refuting the claims. "I have never dealt hash," the councillor told CBC reporter Jamie Strashin.

Arguably one of the most enigmatic figures in the Ford firmament is Rob’s wife, Renata.

She can be seen in a photo taken on the night of Rob Ford’s 2010 election win, but she has only appeared in public on a couple of occasions. Renata's personal details seem to be among the most closely guarded secrets in Toronto. No one appears to know her age, or even if she has a job.

The state of Rob and Renata’s marriage was long a source of speculation; what was known paints a troubling picture.

In 2008, a domestic dispute at the Ford residence led Renata to call 911. Rob Ford was subsequently charged with assault and threatening death. The case went to court, but prosecutors withdrew both charges, citing inconsistencies in Renata’s statements.

While she made rare public appearances with her husband, she shows up inMayor Rob Ford: Uncontrollable, a 2015 memoir by Ford’s former chief of staff, Mark Towhey. In it, Towhey recalled a heated phone call in June 2012 in which Ford talked about "putting three bullets" in Renata's head.

While familial drama often coloured Ford’s political career, it was also clear that his family had his back every step of the way – no one more than Doug.

If you needed evidence of the brothers’ deep bond, it was there during that much-anticipated news conference on May 24, 2013 — Rob Ford’s first media appearance after reports of the crack video.

At the end of his stonewalling four-minute speech — in which he stated, “I do not use crack cocaine, nor am I an addict of crack cocaine” — Ford conveyed his gratitude to those who stood behind him throughout the scandal, including the man who at that precise moment was standing right beside him.

“I want to thank my best friend, and I love him dearly, my brother Doug,” the mayor said.

The 2010 municipal election had been doubly triumphant for the Ford family — not only did it make Rob Ford the chief magistrate of the City of Toronto, it elevated the political status of his older brother. Doug Ford won Ward 2 Etobicoke North, the constituency Rob vacated for his mayoral run.

For four years, only four seats separated the brothers in the first row in the council chamber.

In Rob’s final months, Doug once again assumed the role of his brother’s keeper.

City hall watchers felt their professional relationship was cozier than that. Canadian novelist and Toronto resident Margaret Atwood referred to them as “the twin Ford mayor(s).”

On more than one occasion, Doug stepped in to defend or clarify positions held by his brother — whether it was Rob’s decision to skip Toronto’s annual gay pride parade, to deny his culpability in a conflict-of-interest case or allegations that he was intoxicated at a street festival.

That familial concern became even more apparent during the crack-smoking controversy — after Rob read a prepared statement to a room full of journalists on May 24, for example, it was Doug who remained to field questions.

While Doug often provided public support to his younger brother, his role became even more pronounced in the fall of 2014, after Rob was diagnosed with pleomorphic liposarcoma, a rare but aggressive type of malignant tumour in his abdomen. Because of his health issues, Rob pulled out of the race for mayor, and instead ran for (and won) his old seat in Ward 2. Doug subsequently jumped into the mayoral race, hoping to leverage the family name and the hopes of Ford Nation to defeat John Tory.

Tory’s decisive win, combined with Rob’s ill health, ultimately took the Ford name out of the headlines for many months. But the dire outlook for Rob’s health brought him back into the spotlight.

In Rob’s final months, Doug once again assumed the role of his brother’s keeper.

It was Doug who announced in the fall of 2015 that doctors had found two new tumours in Rob’s bladder. And when Rob was in palliative care in early 2016 and too weak to speak, it was Doug who was out in front of the media keeping the public apprised of his increasingly bleak progress.

"It's a fight," Doug told CBC News at one point. "It's like politics. You're up one day, you're down the next. It’s a challenge."

Every politician can speak to the frustrations of public office: the resistance to policy changes, the unblinking media scrutiny, the fickle opinions of voters.

Given his complicated, contentious personal life, it’s likely Rob Ford understood those challenges better than most.