December 8, 2016

Aleppo is a state of mind. It has to be. So much of what the “jewel of Syria” once was has been destroyed that the only place it can exist without its blood-soaked edges is tucked away somewhere in the corners of memory.

For a foreign news crew trying to reach the city, the road to what’s left of it begins at the Masnaa border crossing between Lebanon and Syria.

It sits in the rocky hills just east of the Bekaa Valley, once an easy and free-flowing vein between Syria and what many considered its client state, Lebanon.

That was before Lebanon’s Cedar Revolution in 2005 pushed Syrian troops and a pro-Syrian government out. But travel between the two countries remained relatively free until 2015.

That’s when Lebanon introduced new visa restrictions for Syrians, as it was no longer able to cope with the large numbers of people flowing into the country. One in every four people now living in Lebanon is said to be a Syrian refugee.

To get to Damascus, you drive across a short no-man’s land through craggy hills until you spot the unexpected — the bright orange and pink lettering of a Dunkin’ Donuts sign, part of a duty-free complex.

Just beyond that is your first encounter with Syrian intelligence. Bags and suitcases are pulled out of vehicles onto a long concrete counter, turned inside out and thoroughly examined.

Any technical contraband is politely removed and ticketed so you can collect it on your way out again. That means anything with a functioning GPS navigation system. Our Bgan satellite, a transmission device, didn’t make it through.

The officers also make note of the IMEI identifier numbers on all our computers. All the better to see you with, my dear.

In the big arrivals hall of the customs building, the lights flicker on and off while we line up with our numbers to collect our visas. The duty commander in charge invites us to sit in his office and sip small cups of coffee while we wait.

"Donald Trump won’t help Syria. Only guns will help Syria."

He smokes and talks about the results of the U.S. election.

“Donald Trump won’t help Syria,” he tells us. “Only guns will help Syria.”

And then we’re on our way, passing a few burnt-out cars and a Syrian soldier sitting on the ground, splitting a pomegranate.

Damascus is just under an hour’s drive from the border. You don’t have to look too hard to see evidence of the war, or to feel it, when you get to the city.

There are checkpoints everywhere, trunks opened, peered into and shut again, especially in the narrow streets of the old city.

Every now and again there’s some shelling, the Russian embassy being the target of choice for rebels based in the towns and suburbs on the outskirts of Damascus.

They’re usually answered in pretty short order by a government airstrike.

You can feel the confidence of the Syrian regime on the streets. There is life on them, bustling commerce and young lovers holding hands in parks.

Whether or not people support Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad is almost irrelevant in the current climate. There is no uncertainty about who is in charge in the capital, unlike the years immediately following the 2011 uprising against the Assad dynasty.

Back then, you could slip behind Syrian army lines to witness the nightly protests in the suburbs controlled by the Free Syrian Army — streets blocked with stones and burning tires to stop tanks from entering. The city was edgier. Neighbour was starting to inform on neighbour as sectarianism took root.

Today, the guns in the hills around the city are slowly growing quieter, Syrian troops encircling rebel enclaves on the outskirts of Damascus and employing starve-or-surrender tactics.

It's the same strategy the army has been using to devastating effect in shell-shocked eastern Aleppo.

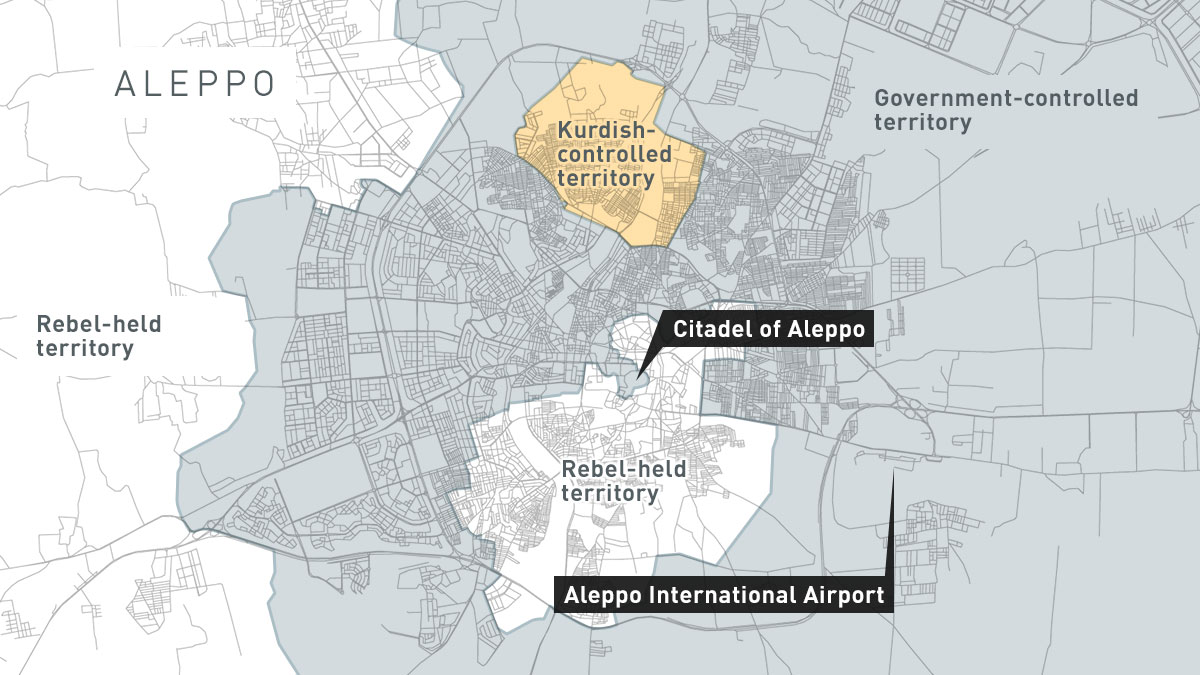

After four years of stalemate in what was once Syria's largest city — not to mention its economic hub — the regime clearly scents victory in Aleppo.

The regime clearly scents victory in Aleppo.

When we go to pick up our permission papers at the Ministry of Information, talk is of an imminent and decisive end to the battle of Aleppo.

Weeks, not months, they say.

We leave Damascus the next day, our two-car convoy loaded up with gear and a government minder. The Syrian soldier at the last checkpoint on the way out of town asks us where we’re going.

When we tell him Aleppo, he says, "God bless you."

The drive from Damascus to Aleppo takes about six or seven hours, with all the military checkpoints and detours around territory held by one or another of the rebel factions fighting the regime, from jihadist groups including Jabhat Fateh al-Sham to the Free Syrian Army.

The drive is a rolling snapshot of the country's fragmentation — and how many foreign players are involved on the ground, especially in support of the Syrian government.

Driving to Aleppo

Driving through the destruction in Aleppo. (Richard Devey/CBC)

Ammunition convoys and tanks carrying Russian soldiers rumble along the road from Homs towards Aleppo. The green-and-yellow flag of Hezbollah, the militant Shia group from Lebanon, stands out against a dun-coloured desert at one of their bases in the north.

It's estimated that as many as 5,000 Shia militiamen from Iran, Iraq and Lebanon are supporting the Syrian government in the battle for Aleppo. The numbers are equal, say some, to those of actual Syrian soldiers fighting.

The last few kilometres into the city are the most treacherous, drivers turning on a burst of speed down the final stretch of a road snaking along one of the conflict's dividing lines. Barriers made of oil barrels and sandbags shelter vehicles from view part of the way.

And then you’ve arrived in the upside-down world that is western Aleppo. University students stream out of campus at the end of the day, frustrated drivers honk in traffic jams and Syrian fighter jets fly overhead, dropping bombs on the other side of the city.

Our timing coincides with the resumption of government airstrikes in Aleppo, after a pause of some weeks.

The strikes are unrelenting, starting in the morning and still shaking you awake in the middle of the night with every thud.

We choose rooms at our hotel to face east so we can film the airstrikes. Great plumes of smoke rise up and hang in the sky like exclamation marks after each missile hits.

The face of the hotel is a reminder that fire comes in the other direction as well — most of the windows are boarded up or reinforced with sandbags to guard against mortar fire. Russian soldiers sit in the lobby.

The eastern side of the city, controlled by rebel groups, is largely obscured from us apart from the increasingly dire reports filed on social media by activists or ordinary civilians living there — hospital after hospital reportedly being hit until there are none left.

In some parts of western Aleppo, the east is quite literally concealed from view by big sheets hung across streets on the front line to obscure the vision of would-be gunmen.

There’s something awkward and intimate about these sheets — it's as though you’ve stumbled into somebody’s bathroom and are looking at them behind a shower curtain.

Syrian soldiers lead us up into one of their positions in a neighbourhood called Bustan al-Qasr so we can peer through a rifle hole in the wall. The damaged buildings on the other side, with their fronts blown off, look like open-face sandwiches. There is little sign of life.

Two school girls emerge from the same front-line building, hair brushed and weighed down by backpacks. They duck under the sniper sheet and walk out past a checkpoint surrounded by sandbags. Men and women sit beside it holding rifles.

The children still live in the building, and it is disorienting to see them walking past all the sights and sounds of conflict on their way to school.

We try to talk to people living along the front line, but few want to show their faces on camera. One woman does stop, saying it’s her duty to talk to us, but we’re not sure if that’s because of the government minder standing with us.

Two school girls emerge from the same front-line building, hair brushed and weighed down by backpacks. They duck under the sniper sheet and walk out past a checkpoint surrounded by sandbags. Men and women sit beside it holding rifles.

The children still live in the building, and it is disorienting to see them walking past all the sights and sounds of conflict on their way to school.

We try to talk to people living along the front line, but few want to show their faces on camera. One woman does stop, saying it’s her duty to talk to us, but we’re not sure if that’s because of the government minder standing with us.

“Really, we need peace, in the east and the west of Aleppo,” a gentle doctor named Haithem Kurabi tells us when we meet him at the University Hospital.

He came out of retirement to run the emergency department because of the added workload delivered by conflict.

"People in the east [are] our family and our neighbour... are not our enemy. We need to shake hands together and live again."

Sniper victim and his mother

This man was shot in the stomach by a sniper. (Richard Devey/CBC)

But a young man lying in a hospital bed upstairs, shot through the stomach by a sniper, says he can't bear the thought of returning to his old home and the neighbourhood where he was hit.

The scars of this war are many, and not all of them are physical.

On another front line, a 20-year old Syrian soldier says he has killed people in the war and also carried the bodies of dead comrades. "I lost any feeling from the moment the rebels entered here," he says, describing himself as a "machine without a heart."

There are other kinds of wounds in Aleppo. Residents wear the loss of the city's cultural heritage like a tear across their hearts.

Aleppo’s old city, including its medieval souk (market) and the winding streets at the foot of its ancient citadel, were declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986, a treasure trove of Islamic art and architecture.

The citadel still stands, and is under Syrian army control. But below it lies a vast ruin, destroyed by fierce fighting between the two sides since 2012.

Syrian soldiers lead us into what’s left of the old city. We walk inside, stepping through holes blasted through walls and a rabbit warren of pathways to avoid the ever-present threat of snipers outside. The rebels still lob shells into this part of the city.

The only living beings we meet aside from the soldiers are street cats and the odd looter or two.

One shopkeeper who has refused to leave makes a bit of money selling falafel and sweets to soldiers from his damaged premises.

A Syrian commander named Abu George Dayoub echoes the confidence of the regime back in Damascus.

"We don't worry at all," he tells us when asked about the battle in other parts of the city. "In fact, we are happy. We have [the rebels] surrounded and they will have to surrender."

We can't stay to witness the final battle for Aleppo, if that is indeed what it is. After five days in the city, our government permissions to be there expire and we rise early to make the journey back to the Syrian capital — although not so early that we'd have to drive in the dark.

When we arrive back in Damascus, we hear that the university hospital we had visited in western Aleppo earlier in the week has been shelled. And that the day before, the hospital administrator who'd introduced us to Dr. Kurabi had been killed when a mortar landed on him as he was crossing the street.

Our Damascus hotel is full of aid workers from the UN and the World Food Program, seas of computers glimpsed in hotel ballrooms normally reserved for weddings and receptions.

The UN's special envoy for Syria, Staffan de Mistura, is expected soon, his arrival coinciding with another one of those occasional spikes of concern that appears when human suffering manages to puncture through the bubble of an indifferent world.

De Mistura is a polite and elegant man schooled in the ways of international diplomacy. But he knows failure when he sees it. We see him sitting quietly by himself in the courtyard.

At the inevitable press conference, the customary lines when dealing with the Syrian quagmire are delivered quickly. "We are running out of time. The UN has a moral duty to continue putting pressure, saying the truth and pushing for stopping this horror."

And there's a warning to the west: It's in your own interest to help stop it.

"Imagine simply by Christmas, as I had feared, due to military intensification, you would have the virtual collapse of what's left in eastern Aleppo," de Mistura says. "You may have 200,000 people moving towards Turkey. That would be a humanitarian catastrophe."

"You may have 200,000 people moving towards Turkey."

Later, I bump into him in the elevator and he pulls me over for a chat. He wants to know about our time in Aleppo. But everyone already knows about Aleppo.

With the world distracted by Donald Trump and with Russian and Iranian airpower and Shia militias on the ground, there is little incentive for the Assad regime to acquiesce to calls for a truce or a diplomatic process that would inevitably be infused with calls for his removal from power.

And he is not without support in Syria. One of Assad's most successful strategies of the war has been to target and remove the middle ground, to challenge the notion of a viable and moderate opposition.

Many Syrians believe Assad when he says the choice is between his own secular regime and a band of Islamic extremists that will unleash even more barbarism across the country.

It is, say some, now simply a matter of the lesser of two evils.

The day we leave Damascus to head back to Lebanon, the young men who studied tourism at school and now work at a hotel in a city where tourists won't come ask shyly for our opinion of Syria.

Ask them the same question and they look around, checking to see who might be listening. No matter what happens in Aleppo, they say, Syria has no future.

No matter what happens in Aleppo, they say, Syria has no future.

"All our friends have left," says one, saying his sister is now living in Amman, Jordan. He's lucky, he says, because he's the only male in his family. It means he's exempt from military service.

Not so his colleague, who admits to failing his last year of university deliberately so he could avoid having to join the army for one more year.

That might not be long enough.

Aleppo is a state of mind.