Gurgling beneath our paved, sprawling cities are creeks and streams that once teemed with life.

In cities like Toronto, waterways were diverted, culverted, bricked over and generally forgotten.

Today, the rivers flow in darkness through pipes and concrete channels.

It’s a lost world hidden underground.

But there are clues if you know what to look for.

Since the late 1980s, Helen Mills has hunted for those clues in the Toronto landscape.

Leaning on a cane for support, she walks the city like a detective, tracking lost rivers.

She points out unexpected curves in the road, breaks in the urban grid. A stray patch of cattails, a line of willows, a grassy ditch — all hints of the streams that once snaked through the city.

In Toronto’s North York district, a cluster of goldenrod and milkweed sits sandwiched between Highway 401 and a school. A few metres away, water pools under the highway and runs through a culvert into a median.

Mills says these are remnants of Mud Creek.

On a fall day, cicadas whine and, for a moment, it’s almost possible to forget the din of traffic and picture what a thriving ecosystem might have once looked like here.

Mills believes we can find a better way to co-exist with water, and she dreams of returning the watersheds to the surface.

“It’s a pretty desolate spot, really,” Mills admits. “You have to act as if there’s hope, because if you don’t, you’ll be guaranteed to fail.”

Climate change and urbanization are heating and flooding our cities. Restoring buried waterways — and their riverbanks — could be one answer to many problems: cooling heat islands, absorbing carbon dioxide, cleaning the air, reducing flooding and providing a habitat for wildlife and native plants.

Will Canadian cities relegate their lost waterways to the past, or is it finally time to let them see daylight again?

WHY THE RIVERS ARE BURIED

Canada’s three largest cities have something in common — they’re not just built along bodies of water, they’re built over them.

In Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver, those rivers, brooks, creeks and streams supported wildlife and provided food and transportation routes for Indigenous Peoples — and later for the early European colonizers — who fished in them, washed in them and drank from them.

The rivers irrigated farms and commercial gardens in Calgary and ran water wheels in Winnipeg. Roads in Halifax were built along creeks for easy access to fresh water.

But as cities expanded, the water became an obstacle.

In the 1800s, populations grew and polluted the rivers, transforming them into open sewers. Epidemics of water-borne diseases such as cholera and typhoid broke out.

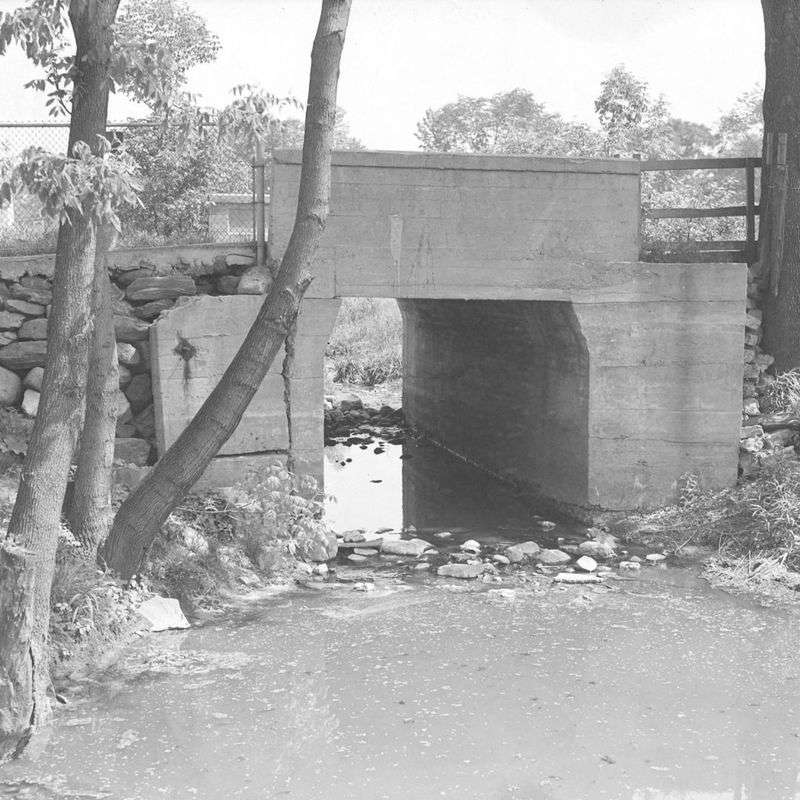

Engineers argued that covering and confining rivers was a convenient way to rid cities of foul-smelling sewage and a way to free up a scarce and valuable resource — land.

So the brooks and streams were re-routed, bricked over and buried in pipes.

“It took 200 years to mess up the rivers. And they were messed up for good reasons — like, we’re not dying of cholera and typhoid [anymore],” Helen Mills says. “But there were many unintended consequences.”

Those consequences are still being felt today.

When heavy rain, intensified by climate change, pours onto hard, concrete surfaces, it searches for the path of least resistance. Creeks can help absorb stormwater and carry it away, but in an urban setting, the water often goes to the only place it can — flooding back to the surface.

In Toronto, the story of Mud Creek echoes many like it.

What we know of its ancient watery path was pieced together by scouring historical maps and studying the landscape for traces left behind.

Mud Creek’s source now lies somewhere under a tangle of multi-lane highways, above-ground subway tracks and old runways in the city’s northwest, near Downsview Airport.

Helen Mills stands on the grassy shoulder of a busy thoroughfare where the creek’s headwaters used to flow.

Mills founded a Toronto group that offers Lost River Walks and has pieced together the creek’s history — from forest to farmland to airfield. “It was a very gently rolling highland,” she says. “Long before it was colonized, for about 11,000 years or more, people have been here.”

Mud Creek originally ran south for 11 kilometres, through what are now residential neighbourhoods and parks, before flowing into the Don River.

En route, the creek cuts through Eglinton Park.

This was once a cornfield cultivated by a nearby Wendat village of a few hundred people.

Today, plants such as tobacco, sweetgrass, echinacea and sage grow in the Anishinaabe Medicine Wheel garden near where Mud Creek used to flow.

Michele Lonechild, who is Plains Cree and Ojibway, and Ethan Keyes, whose father is Ojibway, are among the Indigenous gardeners who tend to the plants.

They’re mindful of the park’s past.

Keyes, whose father’s family is from the Thessalon First Nation on the north shore of Lake Huron, said small waterways like Mud Creek were fished with weirs by Indigenous communities across Ontario.

“There’s so much history that we’ve kind of paved over,” he says.

Rose-Marie Ayotte, a press attaché for Huron-Wendat Nation, says water is intimately linked to their history. Waterways are not only a source of life, but “a part of how the land is shared, and form the paths our ancestors used to travel by canoe.”

The lost creeks don’t have to be left in the past, says Luna Khirfan, an associate professor at the school of planning at the University of Waterloo.

Khirfan says it was “a huge mistake” to undervalue the waterways, but that was the popular way of thinking at the time.

She studies daylighting — the practice of returning buried rivers to the surface and integrating them into the city.

“It’s really important to bring these streams back to life to help us deal with all the challenges that we’re faced with now — urban heat islands, flooding, pollution, loss of ecosystem diversity,” she says.

Most of Mud Creek’s journey through Toronto is underground, though it surfaces occasionally in nooks and crannies of the city, trickling through narrow ravines.

But along a two-kilometre stretch of its journey, Mud Creek comes fully alive.

The Evergreen Brick Works, once the birthplace of the bricks that built many of Toronto’s landmarks, is a sprawling campus of gardens, forest, trails — and Mud Creek.

Mud Creek meanders through the Moore Park Ravine, then flows over a small waterfall into a series of ponds at the Brick Works.

A heron stalks fish for its next meal as ducks float past lily pads nearby. People stroll through a network of paths and bridges, immersed in birdsong and the thrum of insects.

Luna Khirfan pauses on a boardwalk to take in the view.

“Calm in the middle of the city,” Khirfan says. “I just love it. It’s just so beautiful.”

For her, this is “a really good start” and a hint of what’s possible on a much larger scale. She says creeks are toolkits that can help prevent flooding, restore biodiversity and create community spaces with educational and health benefits.

“In the city of Zurich, they do a really good job,” Khirfan says. “I remember when I was there thinking, oh, I wish we could have this in Canada.”

She describes how in the Swiss city, streams meander through public spaces, flowing under cute red pedestrian bridges and under residential buildings through short culverts.

While Canadian cities aren’t quite there yet, some are on their way.

Toronto’s city council has asked several departments to “explore the feasibility of undertaking an assessment of historical watercourses restoration opportunities” and to report back in 2024.

It’s not a promise that lost rivers will be unearthed — but it does acknowledge their existence and commits to looking for opportunities to recognize them, ranging from signage to full-scale daylighting.

“We’re facing a climate emergency right now,” says Jeff Thompson, a senior planner with the City of Toronto's environmental planning division.

“Watercourses can provide a component of relief from the urban heat island effect, and if we don’t explore opportunities to act on that, then we’re faced with future consequences.”

“The thought process of centuries long ago has shifted,” he says.

It’s a shift Helen Mills has noticed. And she’s hoping it will translate into real action.

Upstream from the Brick Works, Mud Creek runs silently under a portion of Woburn Park.

A row of willows lines a ditch that cuts diagonally through the park, a hint of the water below.

Mills walks the imagined path of the creek, pausing to peer through a sewer grate.

“Imagine if there was a stream running through here,” she says.

Thompson agrees it’s a prime example of the type of location that could be considered for daylighting, though he adds the city would need to do a technical study first.

Thompson says before unearthing anything, officials need to know where all that stormwater will end up, and whether there could be spillover.

Back at the Brick Works, the thriving Mud Creek is a reminder of what’s possible.

“This is not in the realm of ‘I wish,’” Khirfan says. “It happens.”

“If we want to keep labelling our cities as ‘world class’ … we do need to make bold decisions. Decisions that are transformative, that are cutting-edge, that are new.”

While in Toronto momentum builds hope for restoring rivers, some in Montreal are mourning the disappearance of one.

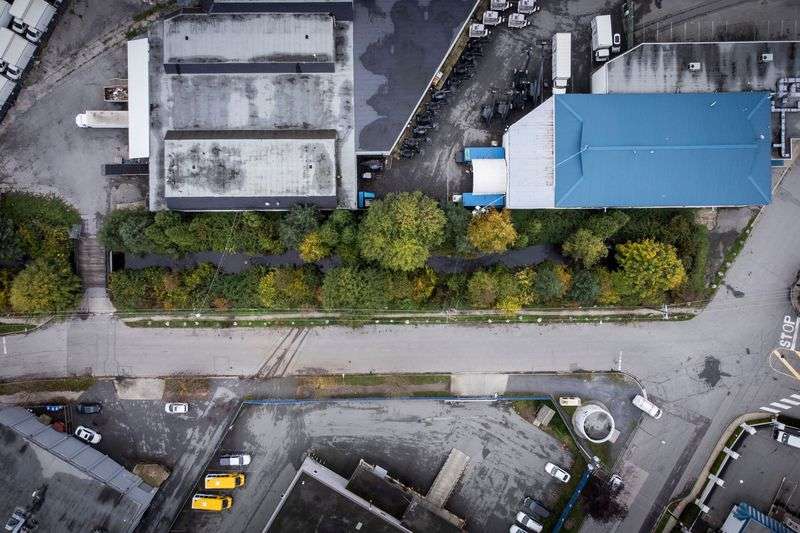

The Island of Montreal has lost about 82 per cent of its original waterways — including, the Saint-Pierre River.

It once ran from the slopes of Mount-Royal down to the St. Lawrence River. And up until recently, a surviving branch still flowed through the Meadowbrook Golf Club in the west end.

But its fate was sealed by a familiar pattern of events.

The river was contaminated with sewage. A legal battle erupted between the company that owned the golf course and the City of Montreal. The court ordered the city to cut off the flow.

In 2022, the last 200 metres of the Saint-Pierre River were erased.

But in the southwest of Montreal, you can still catch a glimpse of the river if you know where to look.

In a small park near the Lachine Canal, a sewer grate offers a window onto the river — or a version of it — as it rushes noisily through the dark.

Kregg Hetherington, an anthropologist at Concordia University, oversaw an initiative to map the river’s path led by students, including Kassandra Spooner-Lockyer and Tricia Toso.

He credits them with discovering this view of the Saint-Pierre.

“My first reaction to it was genuine awe, because we’d been looking for it for a while,” Hetherington says.

He says the fact that so many of Montreal’s smaller rivers have been entwined in urban infrastructure for so long “makes it very difficult to kind of imagine [daylighting] from a practical or policy point of view.”

Past proposals to revive Montreal’s buried streams were deemed too expensive and too complex.

Though the city recognizes the benefits of daylighting, Montreal spokesperson Hugo Bourgoin says it’s often not feasible.

The major challenge, Bourgoin says, is that roughly 70 per cent of Montreal’s sewer system is combined — one shared channel for stormwater and sewage. The waterways can’t be resurfaced without separating the wastewater, something that would require major infrastructure work.

Instead, Montreal is investing in alternatives like sponge parks to help mop up stormwater instead of sending it directly into the sewers.

But a sponge park isn’t the same as daylighting, says Hetherington.

“There’s something charismatic about a river going through a city,” he says.

Not everyone has lost hope that the Saint-Pierre will see daylight again.

In a small park next to the golf course where the river was recently buried, Louise Legault, John Fretz and Peter Lanken discuss the history of the river.

Legault says some people might not think it’s worth it, but reviving the river would connect people with a piece of history, something she believes is important.

She’s an activist with Les Amis du Parc Meadowbrook, which has managed to stave off development in the area for decades.

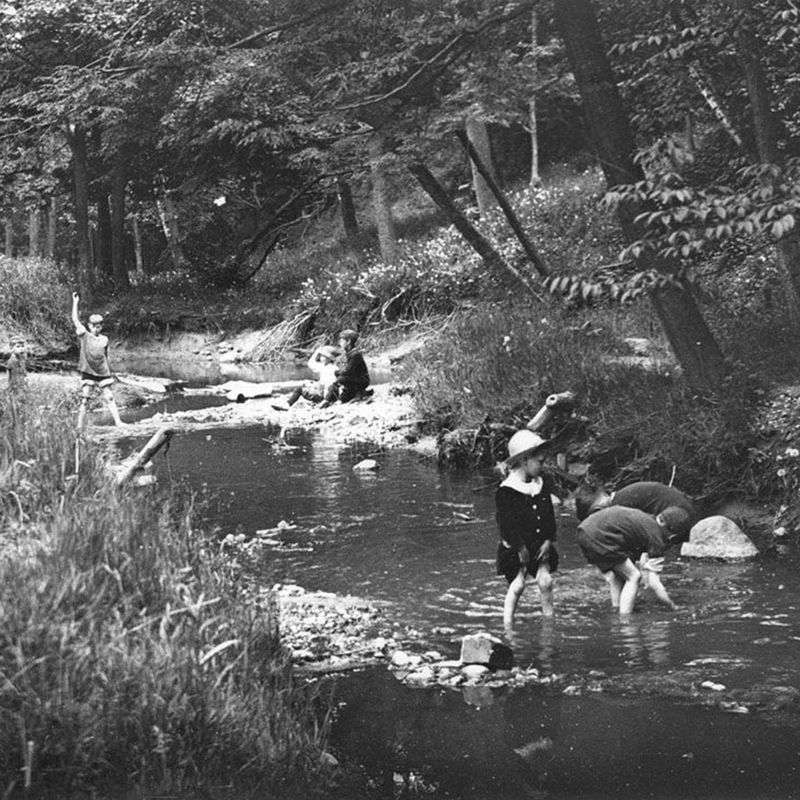

John Fretz has also spent years fighting to protect the area. He grew up playing in the stream and surrounding fields in the 1950s with friend Peter Lanken.

Lanken says the river was about two feet deep in his day, “enough to get what we called soakers in our rubber boots.”

There “we were introduced to how all of life starts,” Lanken says. “We caught leopard frogs and let them go. We caught all the little insects, the water striders and the whirligig beetles.”

“It bothers me that kids growing up today can’t see a stream,” Fretz says. “There’s no connection to nature.”

Tall grasses have overtaken the riverbed in the golf course. Legault worries it will be forgotten. But she says the Saint-Pierre has a mind of its own, and in the spring, the flow returns for a while.

She has asked the Quebec government to recognize the 200 metres of the Saint-Pierre River that run through Meadowbrook as a heritage site. The idea, Legault says, is to ensure the riverbed is protected and cared for until it can be daylighted.

“It contributed to the economic development and the history of Montreal,” she says. “If it is recognized … it would mean that at least they couldn’t fill it in.”

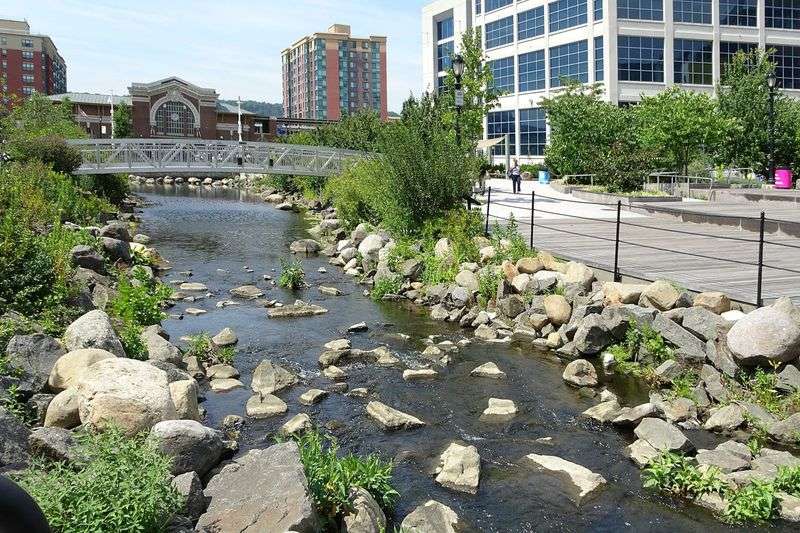

In Vancouver, daylighting lost rivers isn’t a dream or distant hope. It’s a reality.

The story of Vancouver’s lost rivers is like many others — European settlement transformed the landscape and as the city expanded, waterways were buried and confined.

A sprawling network of more than 50 streams and rivers, once used by Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh peoples for travel and fishing, mostly disappeared.

But in the 1990s, a shift in thinking took root, thanks to community stewardship initiatives. By the early 2000s, the City of Vancouver had started to bring its lost rivers back.

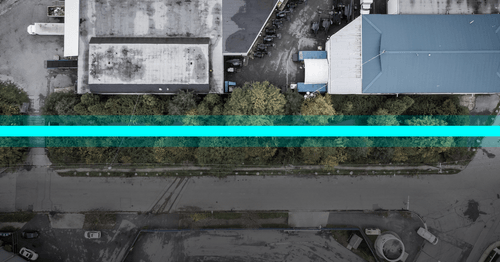

One of those waterways was Still Creek, which flows from East Vancouver to Burnaby Lake, feeding into Brunette River and eventually the Fraser River.

Still Creek was polluted, surrounded in concrete and partly buried, but it was never combined with sewage, making it easier to unearth.

Bit by bit, through city-led work and community involvement, the creek is being restored in segments. It’s taken years to dig up pipes, remove concrete and plant riverbanks with native species.

“This is doable,” says Amir Taleghani, senior flood and drainage planning engineer with the City of Vancouver.

In 2012, for the first time in 80 years, chum salmon returned to the Vancouver portion of the creek. Since then, they’ve come back intermittently to spawn.

Taleghani says it’s one of the last salmon-bearing watercourses in the region.

Not only does daylighting provide a habitat for wildlife and a way for people to access nature, Taleghani says it can also tackle two sides of the climate change coin — it helps cities adapt to extreme weather by making more space for stormwater, while also helping sequester carbon dioxide through the plants that grow along restored riverbanks.

“It’s totally an investment,” Taleghani says. “Taking the nature-based green approach is actually cost-effective, versus kind of concrete, hard-engineered approaches.”

A recent city-commissioned study found that “daylighting buried portions of the creek and widening the creek corridor may significantly reduce the overbank flood hazard.”

It’s one of the benefits of restoring Still Creek highlighted in a recent report, where Vancouver outlines a vision for transforming part of the waterway into a fully daylit channel. It would likely take decades to complete, Taleghani says, with an estimated cost of between $100 and $200 million.

It will be a long process partly because the city has to wait for redevelopment or land-use changes before it can daylight parts of the stream that run through private property.

Though it might not be completed by the time Taleghani retires, he hopes he can one day show his daughter that he helped make a difference.

“Kids nowadays, they’re really going to be living with the future climate,” he says.

“I’d like to have some things to point to, to say, ‘We were trying to make some things better.’”

WHERE ARE THE LOST RIVERS?

Wherever you are, there’s a good chance buried rivers run quietly below, waiting to be rediscovered.

If you live in Toronto, Montreal or Vancouver, you can use this project as a guide to explore where the lost rivers once flowed.

These interactive maps are the best estimates and interpretations of where historical waterways used to flow, based on the work of Paul Lesack with the University of British Columbia, Marcel Fortin with the University of Toronto and Lost Rivers Toronto and Valerie Mahaut with the Université de Montréal.

Lost river maps and guides exist in some other Canadian cities, too, such as Calgary, Winnipeg and Halifax.

Helen Mills invites the public to keep an eye out for signs of lost rivers, from stray willows to flooded ditches to odd bends in the road.

“It’s all about looking at the old maps,” she says, “and then going into the landscape and trying to find the clues.”

A VISION FOR THE FUTURE

As public understanding of lost rivers grows, more cities are adapting how they think about integrating natural watercourses.

Cities like Vancouver, Zurich, Seoul, Yonkers, N.Y., and Dartmouth, N.S., have looked ahead and decided to invest in daylighting their waterways.

“These are cities that looked 100, 200 years down the line and planned … so they reap the benefits,” Khirfan says.

Zurich separated its combined sewer system to cut down on sewage treatment, saving an estimated running cost of about $1.8 million, adjusted for inflation. The city ended up daylighting more than 20 kilometres of urban brooks, revitalizing public spaces and alleviating flood risk in the process.

In Dartmouth, N.S., the first phase of daylighting the Sawmill River went over so well that Coun. Sam Austin says the second phase has “become a ‘when’ not an ‘if.’”

“It doesn’t have to cost hundreds of millions of dollars,” Khirfan says, adding that in the case of Zurich, each segment of daylighting only cost in the range of thousands or tens of thousands of dollars.

Part pragmatist, part visionary, Helen Mills knows restoring lost rivers in a city like Toronto will involve compromise.

“I’m not really into that thing about ‘nature good, city bad.’ I think it is what it is.”

She dreams of reviving Mud Creek in sections, much like the approach used for Still Creek. Her “big crazy idea” is establishing a national park that links the watershed through walking trails and community involvement.

If that came true, “I think I would die happy,” Mills says.

—

All of the maps in this project are meant to serve as general guides to the probable paths of historical waterways, based on the most accurate information available. Due to inaccuracies in historical maps, knowledge of the waterways’ original paths may evolve over time as more information comes to light.

The Toronto waterway maps are based on the work of Peter Hare, Helen Mills and John Wilson with Lost Rivers Toronto (a project of the Toronto Green Community) and Marcel Fortin’s team at the University of Toronto Libraries, who interpreted the paths of historical waterways based on dozens of maps from the 19th and 20th centuries and Digital Elevation Model data.

The Montreal waterway maps are based on the work of Valérie Mahaut at the Université de Montréal, who mapped the historical riverbeds and watersheds of the island of Montreal by referencing historical maps from the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries and by using more recent altimetric data to estimate the trajectories of former watercourses. A more detailed guide to her work is available here.

The Vancouver waterway maps are based on the work of Paul Lesack with the University of British Columbia, who digitized the paths of streams in Vancouver from 1880 to 1920 based on original mapping made by Sharon Proctor in the 1970s.

The black and white aerial photographs of the Saint-Pierre River are from the Archives de la Ville de Montréal and were taken between 1947 and 1949.

For further information about ancient rivers and daylighting, check out Hidden Hydrology and Lost Rivers.

Footer Links

My Account

Contact CBC

- Submit Feedback

- Help Centre

- Audience Relations, CBC

P.O. Box 500 Station A

Toronto, ON

Canada, M5W 1E6 - Audience Relations, CBC

Toll-free (Canada only):

1-866-306-4636 - TTY/Teletype writer:

1-866-220-6045

Services

Accessibility

- It is a priority for CBC to create a website that is accessible to all Canadians including people with visual, hearing, motor and cognitive challenges.

- Closed Captioning and Described Video is available for many CBC shows offered on CBC Gem.

- About CBC Accessibility

- Accessibility Feedback