It has already been a particularly deadly year in terms of people killed in encounters with police in Canada — and Black and Indigenous people continue to be over-represented among the fatalities.

There were 30 people killed after police used force in Canada in the first half of 2020, which is the full-year average for such deaths over the past 10 years (the deadliest year was 2016, when 40 people were killed). This is according to the Deadly Force database, updated and maintained by the CBC’s own researchers.

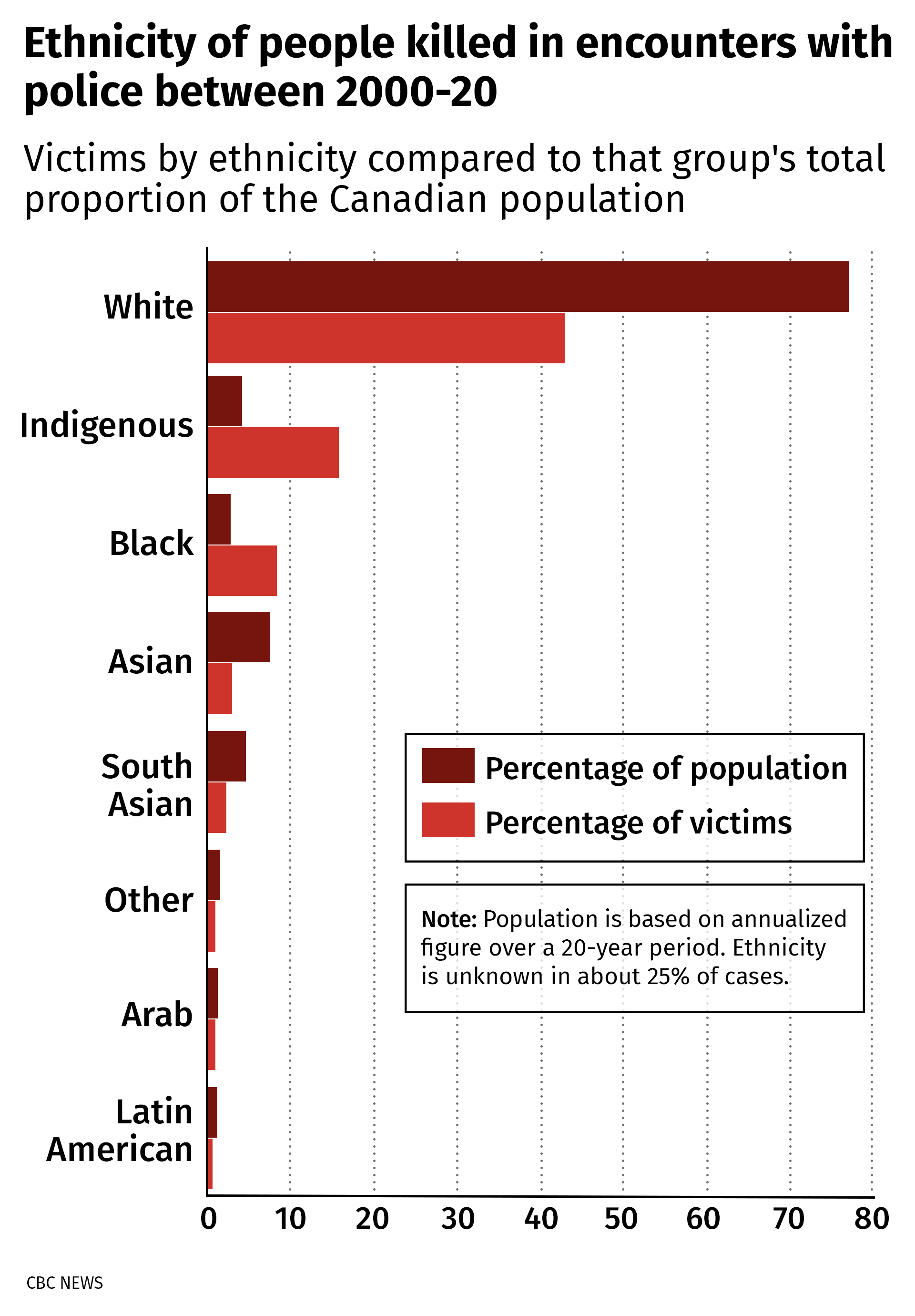

The database shows Black and Indigenous people are disproportionately represented amongst the victims compared to their share of the overall population.

The data also finds most of those killed in police encounters suffer from mental illness or substance abuse.

There is no government database listing deaths at the hands of the police available to the public in Canada, so CBC News created its own. The CBC’s research librarians have collected detailed information on each case, such as ethnicity, the role of mental illness or substance abuse, the type of weapon used and the police service involved, to create a picture of who is dying in police encounters.

The database focuses on fatal encounters where police used force. It does not include in-custody deaths, self-inflicted wounds as a result of suicide or attempts to evade police, or accidental police-caused deaths (such as a traffic accident).

First created in 2018, the database was recently updated to the end of June 2020. Findings have remained consistent, including:

- The number of cases has continued to rise over the past 20 years, even when corrected for population growth.

- Black and Indigenous people are disproportionately represented amongst the fatalities compared to their share of the overall population.

- Mental health and substance abuse issues were present in the majority of cases.

Criminologist Scot Wortley says collecting this kind of data is an important way to hold police accountable.

The University of Toronto professor’s research played a part in Nova Scotia outlawing police street checks in 2019 after his review of data from Halifax Regional Police found that Black people were disproportionately targeted.

“When we get broader statistical information that are documenting these patterns year after year after year, it's much more difficult for police officials and politicians to just turn their backs and say that these allegations are unfounded,” Wortley said.

According to our Deadly Force database, Indigenous people form 16 per cent of the deaths but only 4.21 per cent of the population (annualized over 20 years), and Black people form 8.63 per cent of deaths and only 2.92 per cent of the population. In about a quarter of cases, CBC researchers were unable to confirm the race of the person killed, as the information was not available in media reports, official reviews or other sources.

Akwasi Owusu-Bempah, a professor at the University of Toronto who studies the role of race in the criminal justice system and in policing, attributes the imbalance to systemic issues.

“I think we need to have a conversation about the value of Black and Indigenous life in our country,” Owusu-Bempah said.

“I think in many of these instances the police are justified in using the force that they did, but we need to look at the greater circumstances surrounding these issues and surrounding the environment in which these use-of-force cases take place, and really question as Canadians -- do we want to see our Black population, do we want to see our Indigenous population dying at the hands of state agencies?”

From 2018 to the middle of 2020, there were 97 fatalities in the CBC’s database. Of the 54 cases where race was identified, 19 were Indigenous and four were Black.

Police response to people with mental health issues has also been under the microscope recently, along with the response to people dealing with addiction during the ongoing opioid crisis in many Canadian cities. In recent calls to “defund” the police, experts and activists have pointed to alternative services that could serve these individuals. The CBC data found that 68 per cent of people killed in police encounters were suffering with some kind of mental illness, addiction or both.

Lorne Foster, a professor at York University in Toronto, has studied race-based data in policing. He helped design and implement a project to collect race data on police traffic stops in Ottawa, which found that Black and Middle Eastern people were disproportionately stopped.

“There has to be a reimagination of police services,” Foster said

“I really do believe that the idea behind defunding the police, or the concept of defunding the police, is quite a good one in terms of reformulating how we’re going to exercise policing services in our society.”

Foster says police services should collect this data themselves and use it to inform their policing. “They need to look at this type of data to take the next step and to address these deeply rooted discriminatory features in our society, particularly in relation to their service and the community,” he said.

Tom Stamatakis, national president of the Canadian Police Association, says the trends that CBC identified don’t surprise him — and they won’t change unless underlying issues affecting people with mental health issues and marginalized communities are dealt with.

“When you have people in crises and there’s no other option, often it’s the police that’s going to interact with those persons, and from those interactions we’re going to see, occasionally, negative outcomes,” said Stamatakis, whose organization says it represents 60,000 police personnel.

“Despite the fact that everybody would like to see those negative outcomes become reduced or even eliminated, if nothing changes in our society, it’s unreasonable or unrealistic for people to think that things are going to change.”

Stamatakis said he hears a great deal of frustration from his members about the need for more mental health and other resources in communities to prevent police from having to get involved. He said that the current rallies across Canada are an opportunity for more support for these community resources that are needed to reduce the pressure on police.

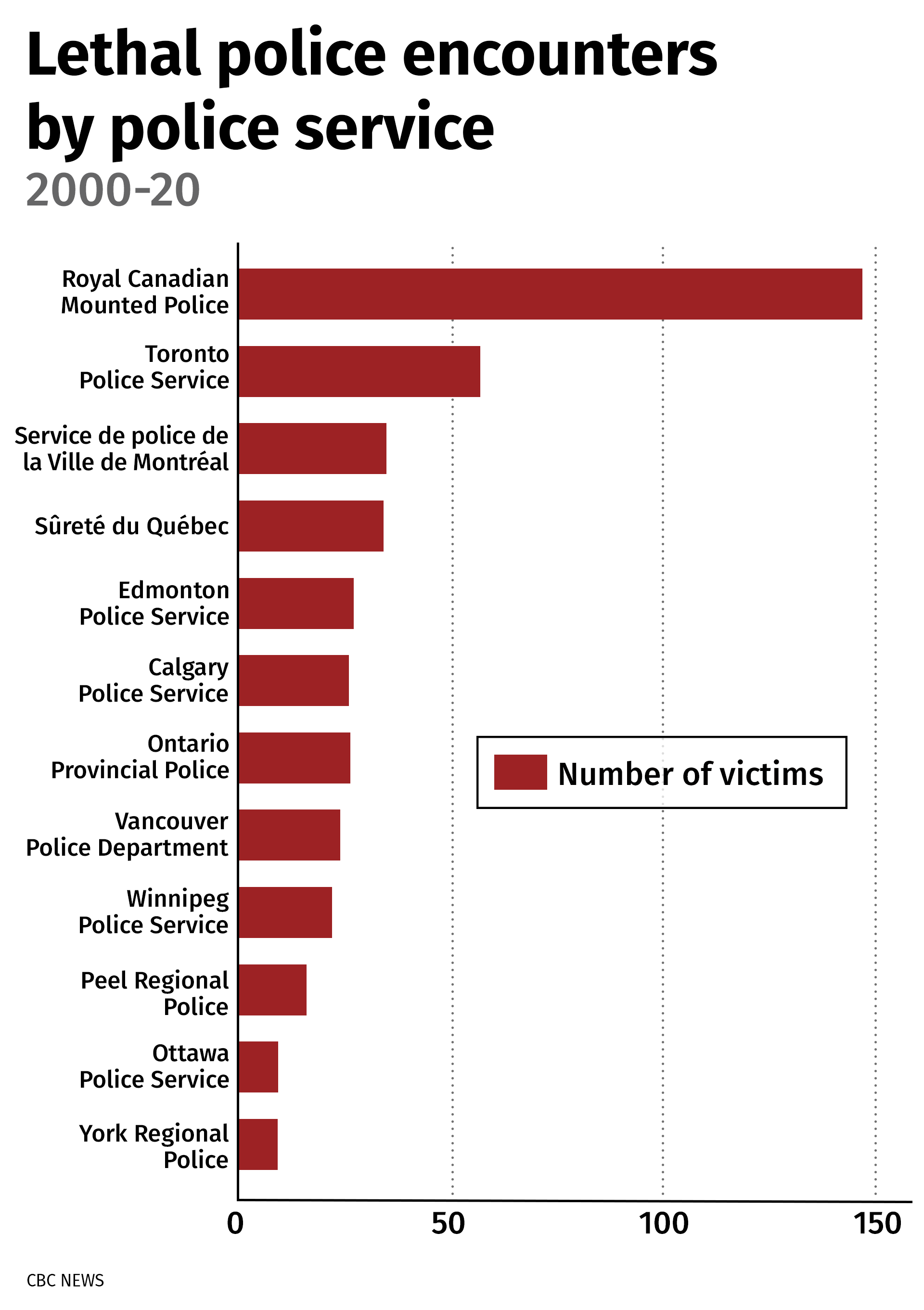

According to the Deadly Force database, the RCMP, which provides policing services to a large part of rural Canada outside of Ontario and Quebec as well as many towns and cities, had the highest number of fatal encounters. This was followed by the Toronto and Montreal police services, which serve the country’s two largest cities.

The RCMP provides frontline policing to a large swath of Canada outside major cities. In a statement to CBC, it highlighted de-escalation and crisis intervention training, which it says is mandatory for all officers.

"Police officers are often the first responders on scene when someone is experiencing a mental health crisis. We have a critical role to play when responding and interacting with people living with mental health problems and illnesses," said the RCMP statement.

Here is the full RCMP statement.

The Toronto Police Service said that its officers are "highly trained in de-escalation tactics to bring what are often complex, highly emotive and dynamic situations to a safe end."