August 15, 2018

Therese Pierrot runs her hand across the splintered wood of her Singer sewing machine.

She’s had it since she was 14 years old, working at a hospital in Aklavik, N.W.T.

For almost 70 years, Pierrot has used the machine to make clothes for her children and community, but with failing eyesight, she decided this year that it was time to let it go.

That's when she went on a search for the sewing machine's original owner. And that's how a woman from Kingston, Ont., ended up in Pierrot's living room in Fort Good Hope, N.W.T.

Around the 1950s, Pierrot was attending residential school in Aklavik when she was pulled out to work at the Immaculate Conception Hospital. Due to a tuberculosis outbreak, there weren’t enough people to work at the hospital.

She lived in the hospital’s basement with 17 other girls, each getting paid $10 a month. They would bake 350 loaves of bread a day, five days a week. One day, the nuns gave each of the girls another $50, because they knew about a local moving sale.

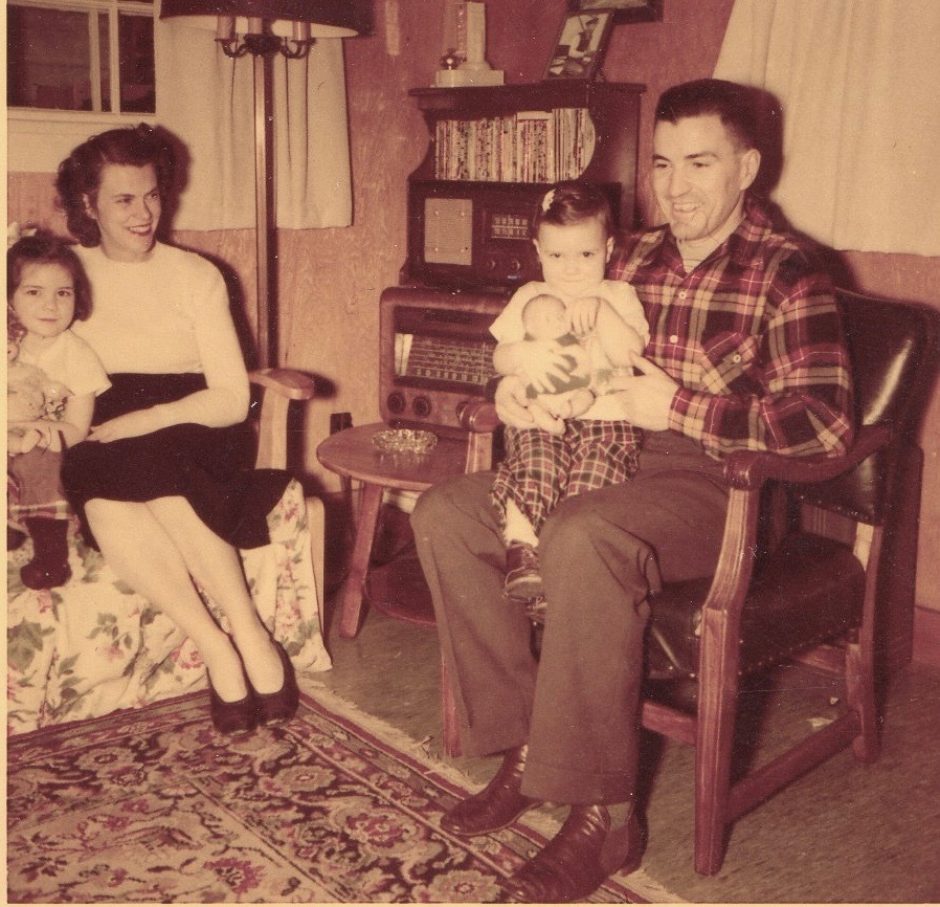

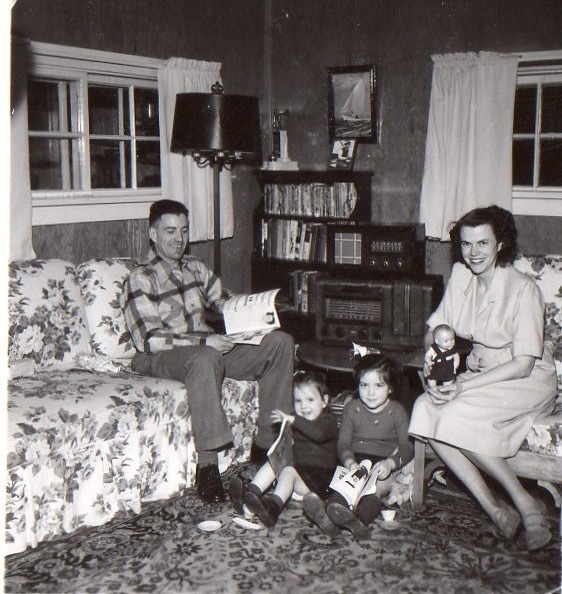

Katy-Lou McLauchlan was married to an RCMP officer, and the family was changing posts.

At the sale, Pierrot said many of the girls went to the dresses and dishes. But the then-14-year-old stopped when she saw a Singer sewing machine.

“I could see my face through this varnish cover for the sewing machine,” said Pierrot.

She said Katy-Lou encouraged her to look at the skirts and blouses, but Pierrot wasn’t interested.

“And I keep standing there, just touching that sewing machine,” said Pierrot. “I said, ‘I wish to buy it, but I got only $50.’”

Katy-Lou said that was fine and covered the sewing machine in a large grey RCMP blanket.

II.

Pierrot couldn’t carry the large machine, so she had the priest bring it by dogsled to the hospital.

She never let any of the other girls touch her sewing machine.

That summer she went home to Fort Good Hope by barge, and she brought her machine with her. But she soon had to return to Aklavik to work at the hospital. For four years, Pierrot’s godmother took care of her precious sewing machine.

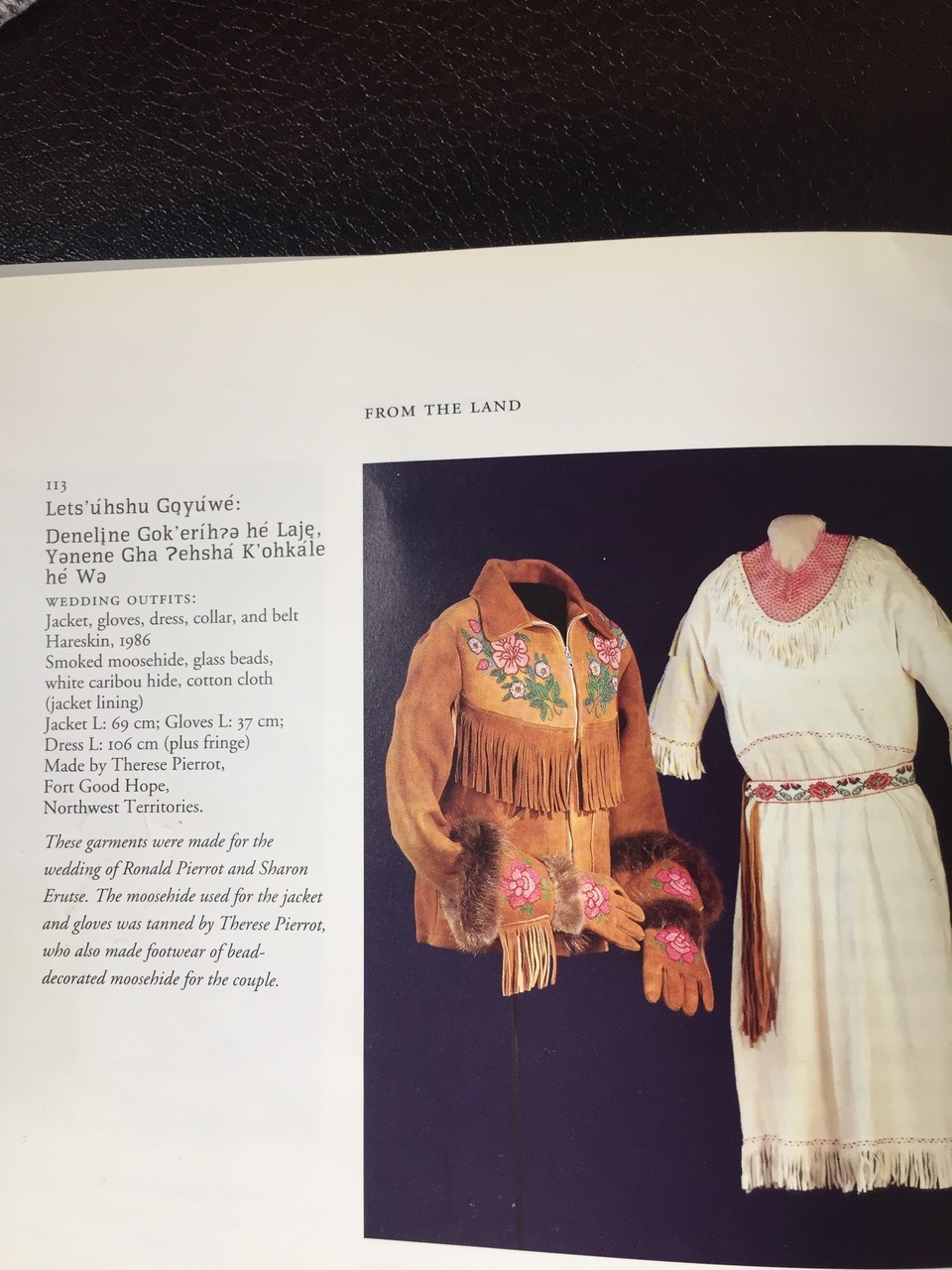

Up until two years ago, the now 84-year-old Pierrot used the machine regularly to make items for her family, like a jacket and a wedding dress for her son and daughter-in-law.

She never used her sewing as a way to make money — she was too afraid of breaking the machine.

“I’m stingy,” she said. “I’m always careful with things that I really like to work with. That’s why I kept it so good all these years.”

The machine has needed repairs over the years. She’s tried to replace a broken belt with a nylon cord and a piece of moosehide, but it just keeps breaking.

She is also blind in one eye, and she's losing her vision in the other.

“If I try to sew now, I might sew my fingers. I can’t see a damn thing,” she laughs.

Pierrot’s family is also making plans to move her to a care home in Norman Wells, N.W.T., and she won’t be able to take the machine with her.

That’s how the search for the McLauchlan family began.

III.

Pulling an old newspaper clipping out of a Ziploc bag, Pierrot explains that she wanted the sewing machine to go to someone who would take care of it.

“I work so hard, I think so hard to save it,” she said.

The newspaper article was about Katy-Lou and Don McLauchlan. Sixty years after their departure, the McLauchlans had returned to Aklavik in 2010 for the hamlet’s 100th anniversary, and to celebrate Don’s 98th birthday.

When it was published, Pierrot had recognized the family as the one she bought the sewing machine from years ago. She kept the article.

“They were ever beautiful,” said Pierrot. “I wish they were here.”

Both Katy-Lou and Don have since died.

But Patricia Manuel, Pierrot’s daughter, thought there might be something she could do.

“I told her I might be able to do some research,” said Manuel.

She searched for their names online and found out they had a daughter named Margaret.

Manuel went on Facebook and says she messaged every Margaret McLauchlan in Canada.

Only one responded.

IV.

It took a few months to get McLauchlan and Pierrot to connect on the phone, but eventually Pierrot was able to tell her the story of the sewing machine. Manuel even sent McLauchlan photos of it.

Pierrot asked if McLauchlan would like to buy it.

“I was shocked,” said McLauchlan.

She promptly booked a flight from Kingston to Fort Good Hope to meet Pierrot.

"Goodbye my sewing machine. You did enough for me."

“It’s like two hands reaching out across the country and connecting over a story. I mean, I feel a heart connection to her,” said McLauchlan.

Though she doesn’t remember that specific machine, McLauchlan said her mother always had a sewing machine.

She does remember some of the items her mother must have made during their time in Aklavik — including two matching windbreakers, made out of a parachute her mother had found on the tundra.

But for McLauchlan, the trip is about more than the physical items.

“It’s not that I want the sewing machine. It’s the story,” she said.

V.

When McLauchlan got to Pierrot’s house, the elder showed her the sewing machine — how it worked and what needed to be fixed.

And then she said goodbye.

“Goodbye my sewing machine. You did enough for me.”

She leaned over and kissed the now-dull varnish of the sewing machine.

“You make lots of things, beautiful things for me. Thank you.”

Now McLauchlan has to get the sewing machine home.

The plan is for Pierrot’s son-in-law to make a crate for the machine and send it to Edmonton by plane. From there, the sewing machine will be put on a transport truck and driven to Kingston.

Before McLauchlan left, she gave Pierrot a mug with pictures of the sewing machine on it, so she can remember it and tell people the story.

“It’s just a story that needs to be shared," said McLauchlan. “And it’s a story that shouldn’t be forgotten."