May 21, 2019

On the evening of Nov. 6, 2018, Emmanuel Vachon and his partner, Edna Lesage, got ready for a chilly sleep in their nylon pup tent.

The temperature dropped to –15 C that night, colder than it had been all winter. Lesage says it was unbearable, so she got up and walked back to her parents’ public housing unit, about five minutes away.

“That little tent was just cold,” she recalled.

Vachon, however, stayed in the tent. He had been kicked out of the house a few months prior. Housing Association rules forbid anyone other than tenants to live in their units. Also, Lesage’s parents weren’t happy with him or his hygiene: his closet, his clothes and his bedding always smelled like urine.

Lesage says that was a problem in the tent, too, including on the night he died.

“He wet on me and in his pants,” she said. “Everything was frozen. He was shivering. He wanted to go with me to my house but my parents said he can’t go there.”

Before she left, Lesage remembers a tender goodbye: “He said, ‘Edna, I love you.’ ‘I love you too, Emmanuel,’ I said.”

That was the last time anyone saw Vachon alive.

Fort Providence, N.W.T., population 695, is nestled along the Mackenzie River about three hours south of Yellowknife. Many of the community’s residents depend on public housing. Fourteen households are on the waitlist for it right now, according to the N.W.T. Housing Corporation.

Lesage says before his death, Vachon had filled out paperwork in the hopes of getting a housing unit, to no avail.

There are very few options for people experiencing homelessness in the community, which has no shelter.

Although most people in Fort Providence, including law enforcement and health officials, knew Vachon was living in a tiny tent with no heat source and likely suffering some form of mental disorder, nobody intervened.

In a series of interviews done in November, Vachon’s loved ones, and many others in the community, were asking how he could have slipped through the cracks so easily. They are still searching for answers to this day.

'Best soup you could eat!'

Emmanuel Vachon was born in Nova Scotia in 1961 and eventually moved to Alberta to work as a lumberjack and then a ranch hand. In the 1980s, he moved to Fort Providence, where he met Lesage. They had two boys together: Rick and Roderick Lesage.

Leone Lafferty lived next to the family in the 1990s and says Vachon was a lot of fun to hang out with.

As she flips through a book of old pictures at her kitchen table, she remembers the time fondly.

“He liked to party and dance,” she said. “He would dance with my mom and stuff like that. He likes to eat peanuts when he's drunk. He’d say, ‘Grab a chair. Have some nuts!’ He was funny. He used to be funny.”

Lafferty also says Vachon was a good mechanic and had a reputation in the kitchen.

“He makes weird soup, too, puts fish, wieners, chicken, all kinds of stuff in,” she said. “‘Best soup you could eat!’ he said. But I never tried it. But a lot of people ate it and they're all still alive. So it's not poison!”

But for all his charm, Vachon had another side. Lafferty said he started changing shortly after his boys were born.

“He used to do weird things,” she said.

She says he once took a chainsaw and cut down a large crucifix in a graveyard. There was also a car chase with police, and the time he had to explain to a judge why he had cut someone’s underwear with scissors. Lafferty is laughing so hard telling this last story, she’s almost in tears.

“He said, ‘That’s the only way I could have sex with her!’”

Eventually Vachon parted ways with his family, checking in periodically over the phone, from prisons and psychiatric wards in Alberta.

Rick Lesage, or “Rick Rock,” as his dad would call him, is Vachon’s oldest son.

The 22-year-old remembers one of those calls from a few years ago, when his dad started losing his memory.

“I called him and he was like, ‘Who’s this?’ And I said, ‘It’s Rick!’ And he was, like, trying to think. He said he didn’t know who was Rick because they kept him in this hospital and they wouldn’t let him out, and he was starting to forget things,” said Rick.

“I was about to hang up … and then he said, ‘Rick? Rick? Rick Rock?’ And then he remembered me, like I brought back his memories or something.”

Rick was the first person to find his father’s body the morning after he died. He was out riding his bike, looking for cigarettes, when he noticed a leg sticking out of his dad’s tent.

“I kicked his leg and right there I knew he was dead, and I started walking back to town and started crying.”

Reconnecting with family

In October 2017 — about 13 months before he died — Vachon returned to Fort Providence, saying he wanted to spend more time with his family. At first he stayed with Lesage — the mother of his two sons — who was living in the bedroom of her parents’ house. He did not get along with her parents, though.

He managed to make the relationship work until the summer, when the police showed up at his bedroom door, telling him he had to leave.

Lafferty lives across the street and came over when she heard what was happening.

“The cop said, ‘Emmanuel? He’s disgusting. How could you be with him? … We can’t even go in that room, it smells like straight pee in there, straight urine.’”

"He's living in a tent ... was it not foreseeable that he would freeze?"

That night, Vachon walked out into the bush and set up his tent in among the birch and pine towering over a clearing that rings the community, known as the fire guard.

Lesage and Lafferty said he was out there most of the summer, except when a social worker sent him to the psychiatric ward in Yellowknife.

When he came back, Lesage said, he had a “big bag of pills.” However, he didn’t want them and made her take them back to the nursing station.

'He put himself in that situation'

In October, winter temperatures started to set in and people noticed Vachon’s face had become almost black. Some people thought it might have had something to do with Halloween, but it was just soot from his oil lamp, which he was using to keep his tent warm.

Lafferty says she was getting worried about Vachon and went looking for help from the authorities, starting with a new social worker, who wasn’t familiar with his history.

“I told her, ‘It’s getting cold and he’s going to freeze,’ … And she said to me and Edna, ‘I can’t help him. He put himself in that situation. So he’s going to take care of himself.’”

Lafferty says she and Lesage also asked the RCMP for help. They were told to get a letter from a nurse saying Vachon, as Lafferty puts it, had “schizophrenia or something.”

Lafferty says the resulting phone calls to nurses and to the social worker resulted in nothing.

'We let him down'

Violet Lafferty, who works at the hamlet’s grocery store, says Vachon was a familiar face on the main street and would often spend hours hanging out in front of the grocery store, asking customers for money.

“I was scared of him a little, but I knew he was harmless. I [helped] him out a little: sandwich, pop, cigarettes.”

At the town’s only bar, Linda Croft remembers meeting Vachon for the first time at a Halloween party in 2017, just shortly after he had moved back to Fort Providence. He was wearing what he wore most days, a big cowboy hat and a long trench coat. Croft, who runs the bar and is also a hamlet councillor, complimented him on his cowboy costume.

“He kind of rolls his eyes and looks away from me. I came to find out it was not a costume, which is probably why he didn't shake my hand,” she said.

Croft said that outfit became a common sight on the main street and also in her bar. She says she would often have to call the police to remove Vachon if he was there begging. But reflecting back, she wishes she had taken a different approach.

“You know, I feel the community as a whole, we let him down,” said Croft. “Here's a man wandering around with, obviously, issues that need to be addressed, and everybody is just letting him go.”

Croft says she knows some individuals tried to help him, but wishes the authorities would have done more to prevent the death.

“He's living in a tent…. Was it not foreseeable that he would freeze, or that he would come to some bad end?”

'Slip through the cracks'

Les Harrison, assistant deputy minister in the territory’s Department of Health, says he can’t comment on specific cases, but he acknowledges “there are all sorts of ways people can slip through the cracks.”

He also emphasizes that when individuals leave the psychiatric ward in Yellowknife, there is a significant effort to create a plan for them with health-care professionals in their home communities.

"People with mental health issues also have the right to make good and bad decisions for themselves."

Harrison adds that authorities can’t force individuals to accept help, unless there is evidence they really are a harm to themselves or others.

“People with mental-health issues also have the right to make good and bad decisions for themselves,” he said.

The Northwest Territories Housing Corporation did not grant an interview about Vachon's application to get housing. A spokesperson for the housing corporation said the corporation does not speak to specific cases, due to privacy legislation, but "is always willing to work with residents to find solutions to housing issues they may be experiencing."

Saying goodbye

Back in her room, Lesage is fiddling with a roll of duct tape, trying to put a blind over her window to block the sunlight.

The walls are bare in her room except for a calendar. The day Vachon died is circled, the words “I love Emmanuel” written beside it.

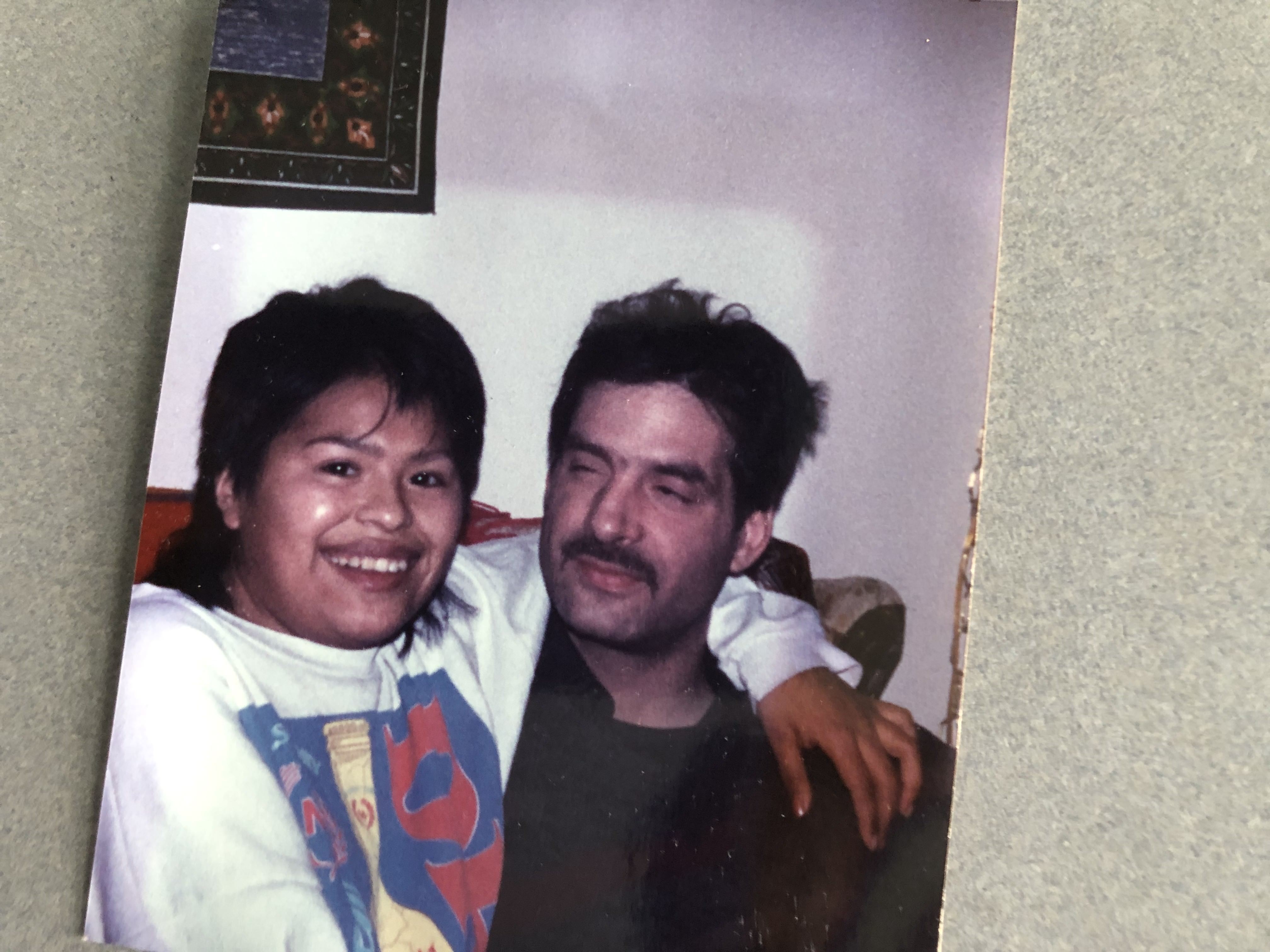

On top of the stereo in the corner of the room is a framed picture of Vachon. The picture is from the 1990s, when the couple’s family was still young. He looks healthy and happy.

Lesage places a cassette into the deck and pushes play. It’s one of Vachon’s favourite country songs, “You Almost Slipped My Mind.”

She sits on the bed, lowers her head, and sings along under her breath. She reaches out towards the picture, her fingertip just managing to touch Vachon’s cheek.

She says he can hear her when she sings.