April 8, 2018

It's just before dawn on a beautiful, still morning in mid-February in Labrador.

Meteorologist Ryan Snoddon, cameraman Bruce Tilley, and I are making our way in the dark to the Goose Bay Airport, our breath showing inside our chilly CBC vehicle. The temperature sits at –23 C, with a wind chill of –37 C.

We pull up to Hangar 14, with the distinct crunch of snow under our feet, as we scramble to get in out of the cold with all of our equipment.

Inside, the bright hangar is a hotbed of activity: nine planes being prepped for a busy day of flying.

The Air Borealis fleet of Twin Otters, planes that are also known as "the aircraft of Canada's North," will soon be deployed for the day, to service six communities along the Big Land's north coast: Rigolet, Makkovik, Postville, Hopedale, Natuashish, and Nain.

These communities depend on these flights — especially during the winter months — as a means of travel, delivering cargo, and bringing patients to and from Happy Valley-Goose Bay for scheduled medical appointments.

But those flights depend on the weather — an unpredictable beast that can clear in an hour, or stay stormy for days. And each of those communities has different topography and weather to contend with.

"If you have rain, drizzle and fog in St. John's, you turn on your windshield wipers. For somebody living in Nain or Natuashish, that means that flight's not coming today," says Philip Earle, the vice-president of business development for Air Borealis.

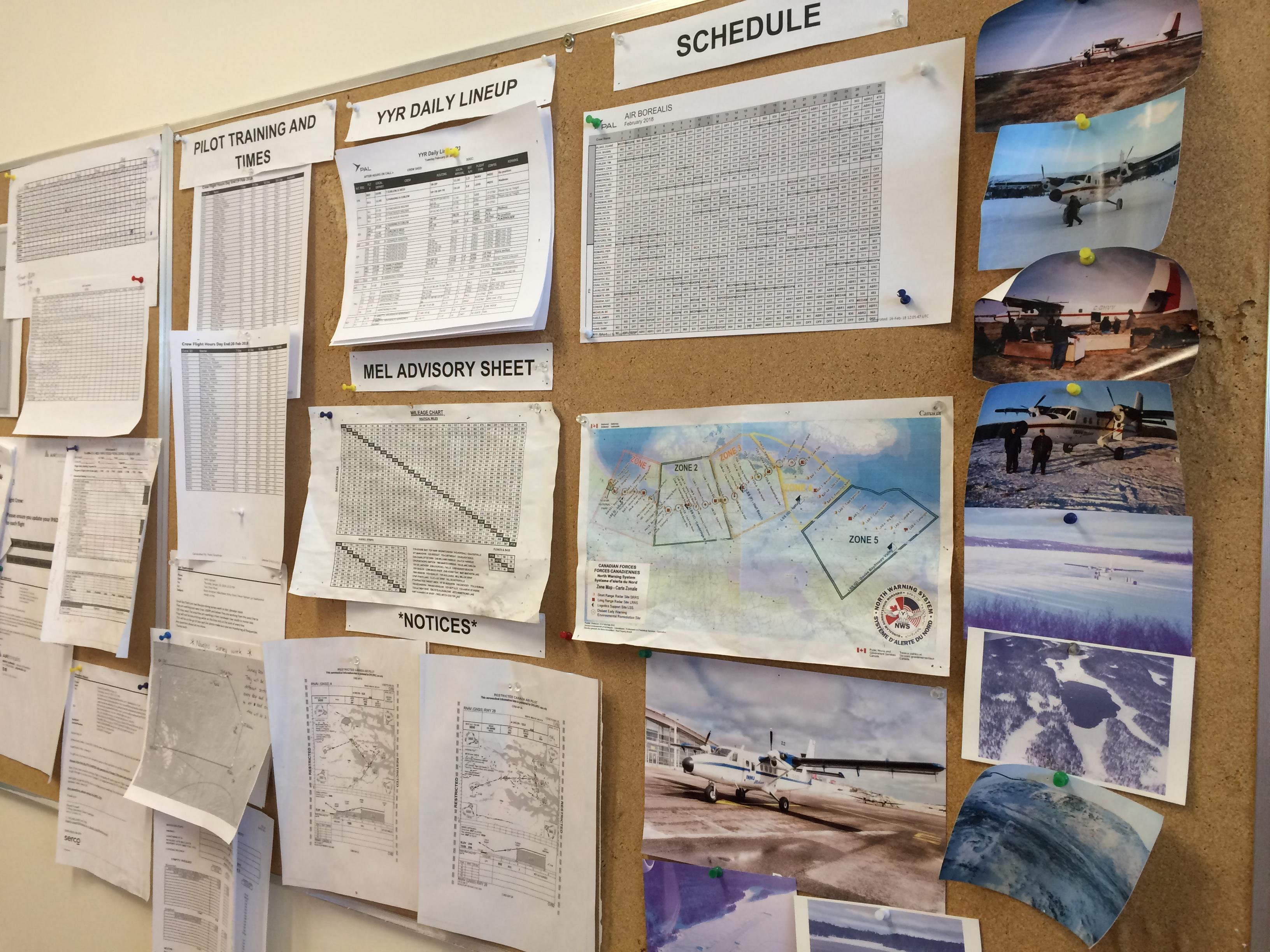

Day 1: At the hangar

Here in the hangar at 5:30 a.m., before the sun's up, the place is abuzz — but this activity actually started hours ago.

"The night shift for the maintenance department, or our aircraft maintenance engineers, they report in the early evening," Earle explains.

"So overnight, they would have been doing the daily inspections, the scheduled maintenance, and any necessary repairs on the aircraft fleet."

One by one, the aircraft are pulled out of the hangar, refuelled, and handed over from the maintenance team to the flight operations team — the pilots who take the aircraft to the warehouse and the terminal building, to load the planes with cargo and passengers before takeoff.

But whether the planes are able to leave, depends on the weather.

Captain Neil Purchase, who has been flying Twin Otters in Goose Bay for the last 15 years, arrives at the hangar for the start of his shift.

"The first thing we check here in the morning is our weather, and our operational flight plan," he says.

"So we'll have a route picked out by our dispatcher and then of course we've got to get the weather that corresponds with that route."

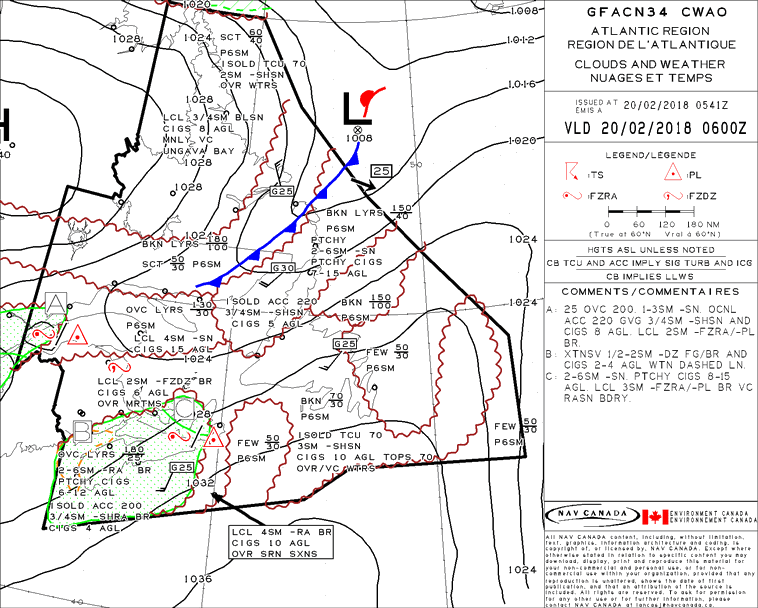

Purchase said the team gets a wide collection of help to map out the weather, including information out of Halifax with the METAR [a coded weather report from the weather observing station], TAF [terminal aerodrome forecast, which is essentially a short-range weather report for aviation], and GFA [a graphic area forecast], as well as local expertise.

"We're also looking for the local knowledge of the strip operators, the agents that are on the coast," he says.

"After a number of years, most of these people got a pretty good grasp on the weather."

Purchase says after his years of flying, he's got thousands of stories. But his most recent tale involved a medevac in Rigolet, and a race against the clock.

"We got out there, a low pressure coming. We knew we had an hour to get there. Young baby got born. And it's not like your typical hospital setting," he says.

"The lady came out, she was in the back of a komatik. The nurse was straddled across the komatik, and the baby was wrapped.

"It's definitely an interesting place to work! Everybody got out safe and sound."

Years of experience

It's mid-morning, a bright, sunny day just outside Hangar 18, Air Borealis's cargo warehouse, and Captain Kevin Hann is preparing for his flight up the coast.

He's been in aviation for 40 years, and the bulk of that time has been spent flying in Labrador.

"It's more exciting I think than flying the bigger aircraft, it's more of a challenge," he says.

Hann says as a pilot in Labrador, he's seen it all.

"There have been some good flights, there have been some not-so-good flights. Pretty well seen... every weather condition that's up there," Hann says.

"The Labrador coast is basically a place where the winds are always blowing fairly hard, and 30 knots is a calm day. And we usually have 40 to 50 knots."

On this particular day in Nain, it's 30 knots of wind, –32 C, and visibility is down.

Hann says there's also a lot of ice at certain times of the year. That's just some of the information he's collected from his years of experience — intimate knowledge of the local conditions, the low pressures, and how to handle onshore winds.

"You gotta watch what you're doing with the weather systems," he says.

"One good thing is that if the weather is marginal or no good, we just call the shot and we don't go.

"We only fly when it's safe conditions to fly on the Labrador coast."

‘Kind of in the blood’

Mid-afternoon, we're back in Hanger 14 with Philip Earle, a friendly Labradorian who's a wealth of knowledge about aviation and the Big Land.

He's been working in the industry since 2000, and takes pride in his work with Air Borealis, which formed in June.

The airline is an amalgamation of businesses from two Indigenous groups in Labrador, the Innu and Inuit, and it's operated by PAL Airlines.

Its logo is an inukshuk: green to represent the northern lights, and stones representing each of the communities it serves.

"[I] grew up in a small community in Labrador where my mail came on an airplane," he says.

"So it's kind of in the blood of every individual that grows up in rural, remote, coastal communities."

Every so often, Earle drops the line, "I'm a talker."

It's obvious he loves to chat about the work for which he's so passionate, and the breadth of challenges he faces in providing services and solutions to people along the coast.

"In a day-to-day, that could mean somebody [calling] you up to book a charter at the very last minute. It could be somebody who has a very important snowmobile part that is being shipped from a retailer... Or it could be something as exotic as getting a billionaire into the Torngat Mountains National Park, and we've done that too," he says.

But there's the added pressure knowing that those plans could change in an instant.

Earle says the longest recent stretch without Air Borealis being able to land in all six communities is a total of 16 days.

"We're seeing a lot more inclement weather that certainly brings flight interruptions," Earle says.

"We're always looking at least two days out."

"That brings another layer of observance or planning to allow us to compensate for what could be extended periods of bad weather. It could be circumstances where we have to add extra capacity."

Food to online shopping

Those delays can have repercussions for the people relying on travel and shipments up the coast — especially food that carries an expiry date.

Earle takes us back to Hangar 18, where cargo is kept before it's loaded onto flights. He shows us one of three large refrigeration units used to store food.

"It breaks down by days... Tuesdays and Thursdays are big days for items going to the coast," he says, noting that milk and other dairy products, as well as vegetables like carrots and turnips are shipped early in the week, while produce like lettuce, broccoli, and spinach go out later.

"Those are moved to the coastal communities late Thursday, end of Friday, to be on the store shelves to be sold when people are picking up their groceries on the weekend.”

But to get to this point, these items have already had to make a long journey: food is shipped from Montreal by boat to St. John's, then trucked to Bay Roberts and across Newfoundland, moved by ferry across the Straits, and ending up in Happy Valley-Goose Bay.

"We're the last link in that [supply] chain."

"When we see a weather system moving in, it's not uncommon for us to basically call up the wholesalers, and say, 'Look, we're going to have bad weather on Tuesday or Thursday. Get the food in early, we'll get it moved early,'" Earle says.

But it's not just food making the trek up the coastline. Air Borealis also ships mail, and Earle says it’s seeing a surge in the amount of packages, due to the global trend of online shopping.

"We can go back to an era when there was one flight every couple of days that would get in, and that plane would have a bag of mail or two bags of mail for each of the communities," he says.

Now, the airline is carrying packages from online retailers like Walmart, eBay, and Amazon, with items as small as a toothbrush, to big-ticket items like bikes, snowblowers, flat-screen TVs, and snowmobiles.

"Whatever an individual would do in downtown Toronto or Calgary or Vancouver in online shopping, it's happening in coastal Labrador," he said.

"People are looking for the best deals."

Setting sun

As the sun sets, it’s a cold and calm evening in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, with a temperature of -22 C and a wind chill of -33 C. But the situation is much different further north.

Our plan is to fly with some cargo to Nain in the morning, on what's called a combi-flight, but that trip is starting to look doubtful. Mother Nature may not be on our side.

Air Borealis employees are in deep discussion in an office in Hangar 14 about a flight that was destined for Nain — but winds in the area are gusting to 100 kilometres an hour.

Captain Neil Purchase says the decision was made to re-route the aircraft to Hopedale, where the winds have died down.

"Some days, you're planning on a forecast that's built at 6 a.m. Come 3 p.m., the forecast didn't play out the way it was meant to," he says.

"And that's fine. People are pretty understanding about that."

Day 2: Flying to the north coast

It's our second day in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, and a much different scene: fluffy snow has slowly but steadily been falling all morning.

Luckily, we're given the all-clear for Nain, where it's -22 C and calling for very light winds. Captain Noel Bennett says it should be a nice, smooth flight, that will take about an hour and 15 minutes.

"Most times in Nain, our biggest concern is the winds. The winds can be very unpredictable... and they can get quite strong," Bennett said.

"That can happen very quickly, and it can die out very quickly."

"But on the Labrador coast, you always got to expect the unexpected."

Our plane is loaded with boxes of cargo: oranges, apples, eggs, yogurt, and many other items that are set to hit the shelves of the grocery store in Nain later that day.

We load our gear, and we're set to speed down the runway, with Captain Bennett and First Officer Guillaume Reid at the helm, lifting up and up into the clouds, at an altitude of about 8,000 feet.

Along the route, Earle points out to me: "This is where the tree-line stop." A stark sea of white, punctuated by the formation of the land, for as far as the eye could see.

Halfway through the flight, Bennett says the flying conditions are good.

"[Winds are] at eight knots. They got 15 miles visibility with scattered cloud layer with a higher overcast," he says.

"When we speak to the aircraft leaving Nain shortly, we'll get a PIREP [a pilot report] from them and we'll find out what the conditions are right now in Nain when they leave."

Bennett says that's how they will decide which approach to make at the airport, from north or south.

"When we talk to the other aircraft that are leaving Nain, we'll get a good idea of what the turbulence and the wind direction is before we actually land," he said.

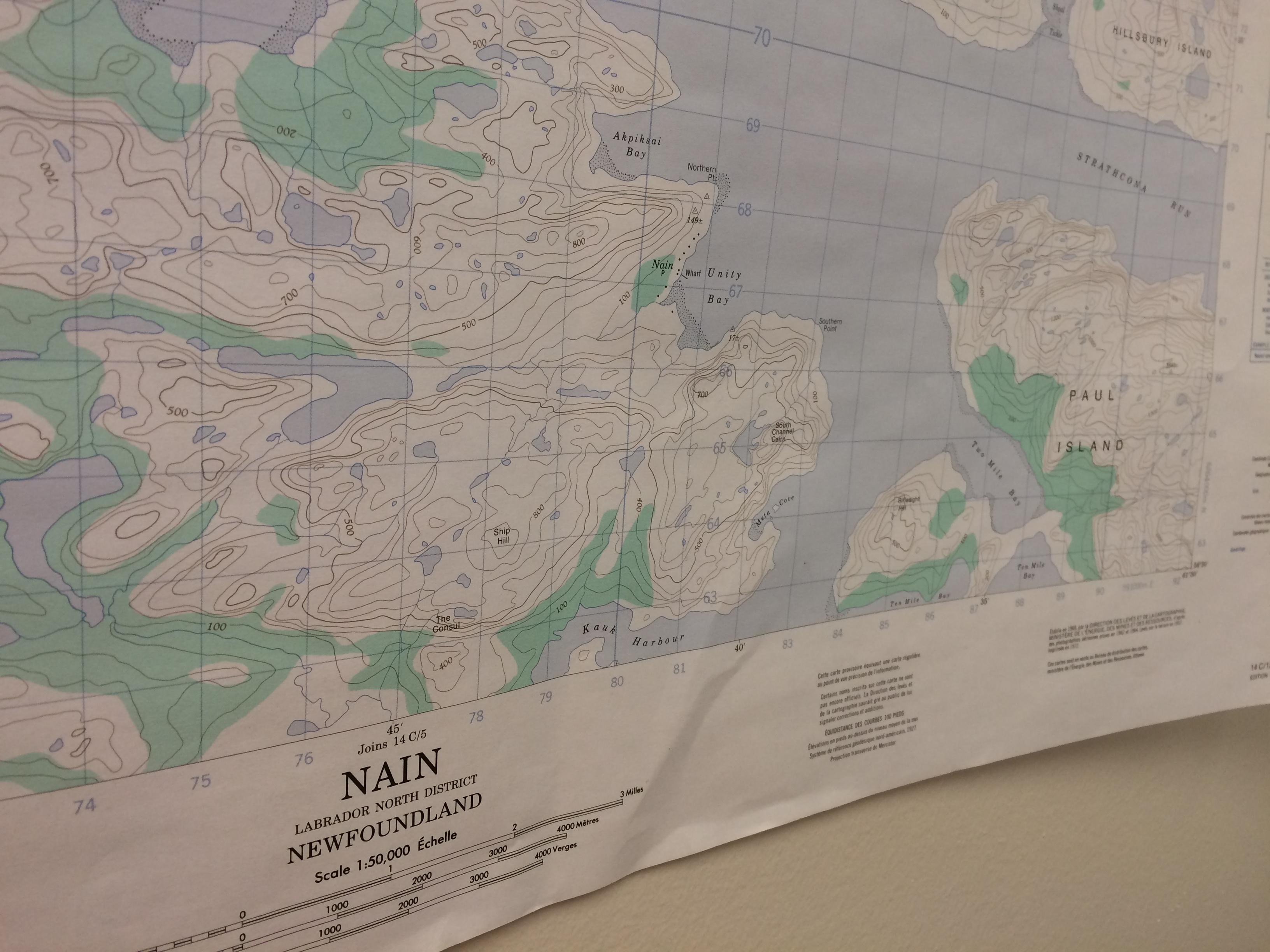

Landing in Nain

It's late morning, and we're making our approach to Nain, circling closer to the remote northern community with a population of almost 1,200.

The gravel runway, which was constructed in the '80s, is one of the most challenging for Air Borealis pilots.

At 2,000 feet long, it's the shortest runway on the north coast. It's also wedged between the ocean and a valley with two hills, which could potentially create a tailwind at one end of the runway, and a headwind at the other.

But ours is not the only flight landing there today. With the winds becoming light and current ideal landing conditions — and some soon-to-be stormy weather on the way — the runway quickly becomes a busy spot.

There’s a flight from Voisey's Bay, an RCMP supply plane, and an Air Borealis schedevac — a flight carrying people to and from the coast for scheduled medical appointments in Happy Valley-Goose Bay.

There's a ground crew waiting for us, but it's not your typical airport setting. There are four or five snowmobiles with komatiks by the small runway, and people from the town waiting to help offload cargo, to bring to one of two grocery stores.

They line up and pass the bundles from the plane, one by one, like clockwork, to the komatiks. There's pop music playing from someone's phone.

Nain is snow-covered, and the only way to get around this time of year is by snowmobile.

I hop on a machine, and the driver asks if I'd rather go through the community or on the ice. She says she usually takes the ice — it's not as bumpy. So we set off on the horizon with our komatik of goods.

The komatik is expertly backed into Big Land Grocery's warehouse, and the goods are unloaded.

Everyone I talk to says we should have been in Nain yesterday — with high winds above 100 kilometres an hour, and a windchill nearing -50 C.

(Though to be honest, I'm glad I'm only hearing about it, and not experiencing it firsthand!)

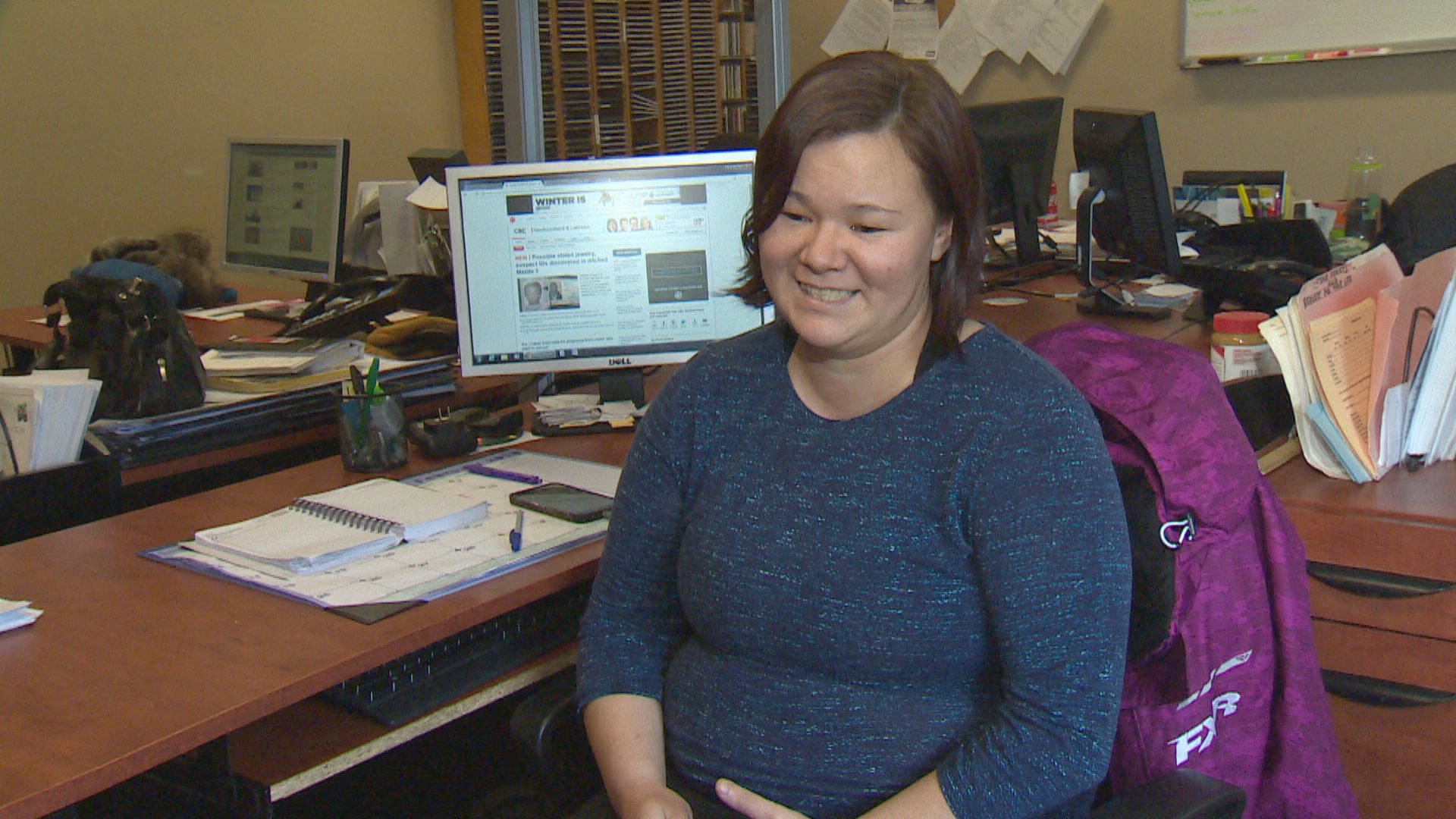

Matilda Karpik, who works at Big Land Grocery, says people in Nain rely on Air Borealis and the goods being shipped in.

"I think the more struggle that I have is with telling the customers, ‘It's not here yet.’ And it's just a waiting process for it to come in," she says.

"I usually stock up, so I won't run out... I stock up on the potatoes and carrots and turnip, the more hard produce."

But it's not just the wait for food — it's being able to pay for it.

Tony Andersen, the former AngajukKak of Nain, was unimpressed when he got to the checkout.

"I just tried to buy a roast that was less than a kilo... $40," he says.

"I put it back. I can't afford that. Not often, anyway."

Andersen says it's difficult to live in Nain.

"Just these few items here is $30. For a little bit of ribs, and dog food, and milk. So it's not cheap," he says.

"I feel really bad for young families who don't have good income. It must be very difficult to feed, to buy yogurt and these kinds of things that kids enjoy."

Arlene Ikkusek knows the struggles of providing for her young family in Nain.

One of the most expensive items on her shopping list is diapers. She says a 132-pack of diapers can cost about $90 in a store.

So, Ikkusek shops online.

"It's cheaper, but the shipping is still like $100," she says.

"If I were to go home now and my son doesn't have diapers, then I wouldn't know what to do, 'cause it's not my payday yet, and I struggle through each pay week... I will have to borrow."

Ikkusek says she turns to online shopping for everything.

"I'll bargain, try to find the cheapest I could find," she said. "Anything my kids would need, I'll go onto the internet."

Heading back down the coast

It's late in the afternoon, and time to catch our flight back to Goose Bay, and then back to St. John's.

It was a short but sweet trip — one that we won't soon forget.

We load our gear into a komatik, and make our way back to the landing strip, heading back down the coast before any weather can slow us down.

While we didn't see any storms during this trip, it's clear that weather is everything along the north coast.