February 24, 2018

A look of shock flashes across Tony Billie's face as he slips from a boat into the dark, frigid water.

The water temperature in Bamfield, B.C., is about 8 C on this February day.

It's a life-threatening situation for anyone who is unprepared.

But Billie, 52, of the K'ómoks First Nation, is wearing a water-tight suit, swimming gloves, and a personal flotation device.

He's in the water for a training exercise at the Canadian Coast Guard's training centre in Bamfield, a village on the remote and wild west coast of Vancouver Island.

Billie is one of nine people from different First Nations taking part in the unique course that combines the knowledge of Indigenous mariners with the search and rescue expertise of the Coast Guard.

The goal is to better equip people who spend time on the water to respond to emergencies in their territory, something they already do, often without equipment or training.

Indigenous mariners have jumped into their fishing boats and mounted rescues for some of the worst ocean disasters on the B.C. coast, including the sinking of the Queen of the North ferry at Hartley Bay in 2006 and the Leviathan II whale-watching tragedy near Tofino in 2015.

Instructor Geoff Carrow hopes the course delivers on both search and rescue skills and on reconciliation.

"There's 63-plus communities along the west coast of British Columbia, and Vancouver Island, and Gwaii Haanas where we can work together seamlessly, share our resources, share our knowledge," Carrow says.

Billie is also here for his own reasons. He lost his brother to the ocean and he doesn't want that to happen to anyone else.

"He was bringing a boat from Campbell River to K'ómoks, on the east coast of Vancouver Island. His boat caught fire and he drowned, so it's pretty hard on me," Billie says.

"This will help me train so I can help other people."

The students in this course hail from up and down the coast, from Musqueam Indian Band in Vancouver to the Heiltsuk First Nation in Bella Bella on the Central Coast.

Billie worked on a commercial fishing boat for more than a decade. Now he's one of three people in his nation's Guardian Watchmen program. That group protects and monitors the land and water within K'ómoks territory.

Right now, K'ómoks doesn't have any formal search and rescue capabilities, he says.

"None. That's why there's three of us as guardians and all three of us are going to take this course to be more eyes and ears on the water to help out wherever we can."

'First Nations have an incredible knowledge of the coast and the waterways.'

The idea for Indigenous training took root several years ago out of a recognition that a better relationship with coastal nations could save more lives, says Carrow, the instructor and a senior officer with the Canadian Coast Guard in the search and rescue program office.

"First Nations have an incredible knowledge of the coast and the waterways and the Coast Guard has a fantastic knowledge of search and rescue techniques and very skilled and trained operators," he says.

"We are trying to combine that so it makes it safer."

Training exercises help students prepare for real rescues in their territories.

Some training has been delivered over the past few years, but it wasn't until the federal government announced its Oceans Protection Plan in 2016 that funding came through to develop and deliver the program.

The result is an intense four-day course in Bamfield that introduces participants to Coast Guard equipment, technology and communications procedures.

"Sometimes if your communications are a bit too casual you can miss things or have inaccurate information going back and forth," says Tyler Brand, a deputy superintendent with the Canadian Coast Guard.

Bamfield is in the traditional territory of the Huu-ay-aht First Nation. The course opens with prayers, songs and a welcome ceremony from Huu-ay-aht member Edward Johnson.

"There is a real true connection. The water is there to provide for us," he says. "It is what connects all of us."

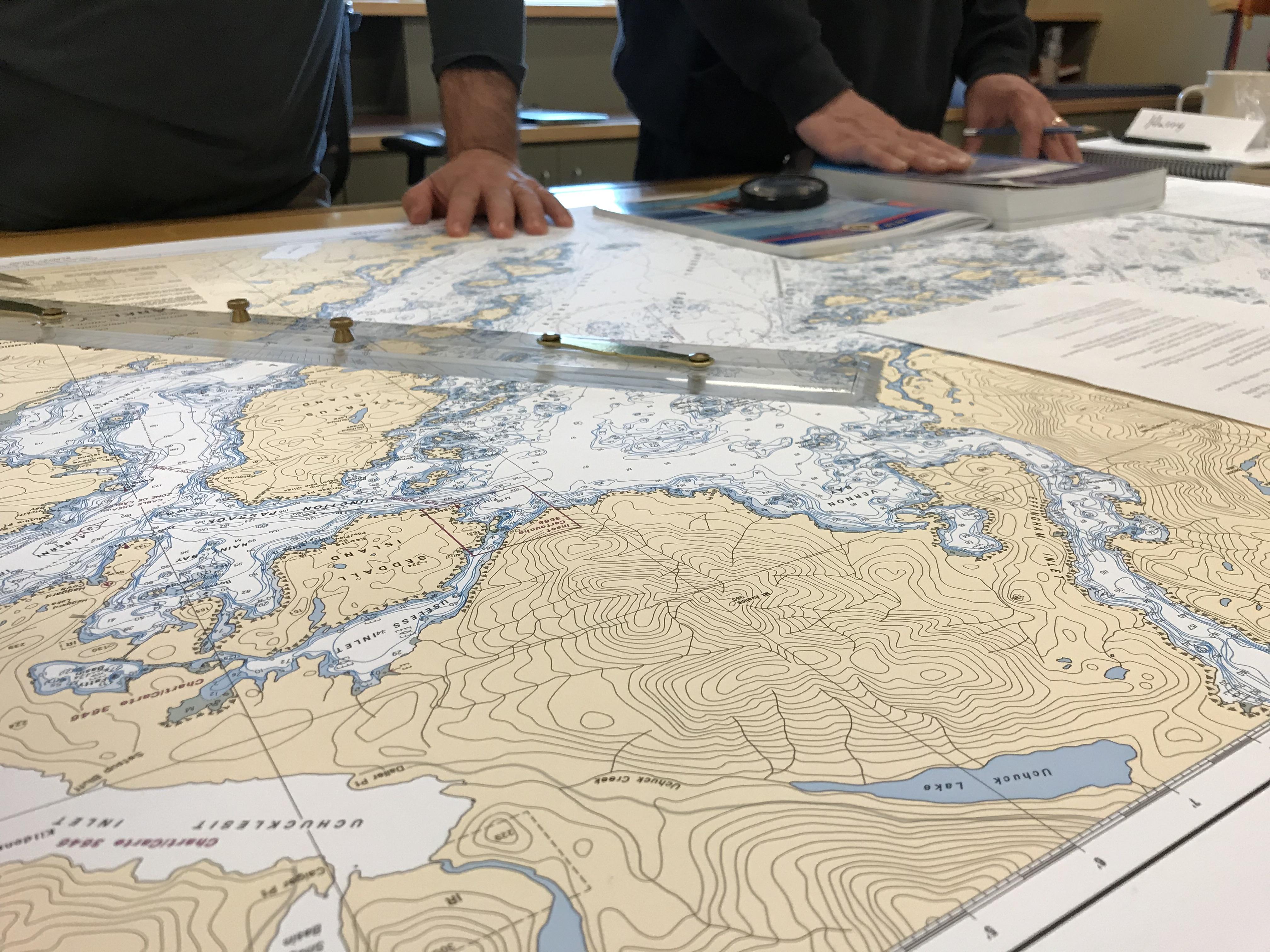

Classroom work includes route planning, risk assessment and rescue theory, such as how to set up a grid pattern for a search.

The class members suit up by pulling on nearly a dozen different Coast Guard garments to steel themselves against the elements. The group then heads out on the water for simulated rescue exercises.

They even conduct mock searches at night. On one occasion, the exercise lasts for more than two hours in storm-force winds.

The skills learned here will help when things go wrong on the water, says Martin Louis, an Aboriginal fisheries officer with the Musqueam Indian Band in Vancouver.

"My job is to look after our fishermen and our community, and make sure our fishermen are safe, and make sure any nearby pleasure craft people are safe."

Participants in Indigenous Coast Guard training hit the frigid water

'Treating us like peers'

The students and instructors also stay together and eat meals together at a lodge in Bamfield. The close quarters create opportunities to swap stories and share experiences.

"There has been a varied history between the Canadian Government and some of these First Nations. Sometimes we will struggle a little bit with trust issues," Brand says.

"But I think the Coast Guard for many years now has been making efforts to work with these communities."

Tim Kulchyski, a biologist with the fisheries department of Cowichan Tribes, just north of Victoria, travelled to Bamfield not knowing what to expect.

"It's really reassuring and reaffirming to have them not look at us as being uninformed or incapable. They have been treating us like peers," he says.

It's the kind of approach that could help change perceptions back home, he says.

"It will start to break down some of those barriers that have existed for far too long."

'Now we are realizing it takes all of us.'

Back at the dock in front of the Coast Guard training centre, Tony Billie has been floating in the frigid water for about five minutes.

With some coaching, he throws his arms over the side of a Zodiac-style boat, bobs up and down a few times, and pulls himself out of the water, executing a self-rescue.

Carrow said the program is a chance to build bridges between Indigenous and non-Indigenous mariners.

But there is more work to do.

Access to suitable rescue boats and equipment remains a challenge in many First Nations communities. A federal promise to establish Indigenous Coast Guard Auxillary units has not yet come to fruition.

New Coast Guard lifeboat stations announced for Victoria, Hartley Bay, Port Renfrew and Nootka have not yet taken shape.

But after these four days in Bamfield, some common ground has been found, says Louis, with the Musqueam band.

"Before there was kind of [stigmas] that separated us," he says. "Now we are realizing it takes all of us."