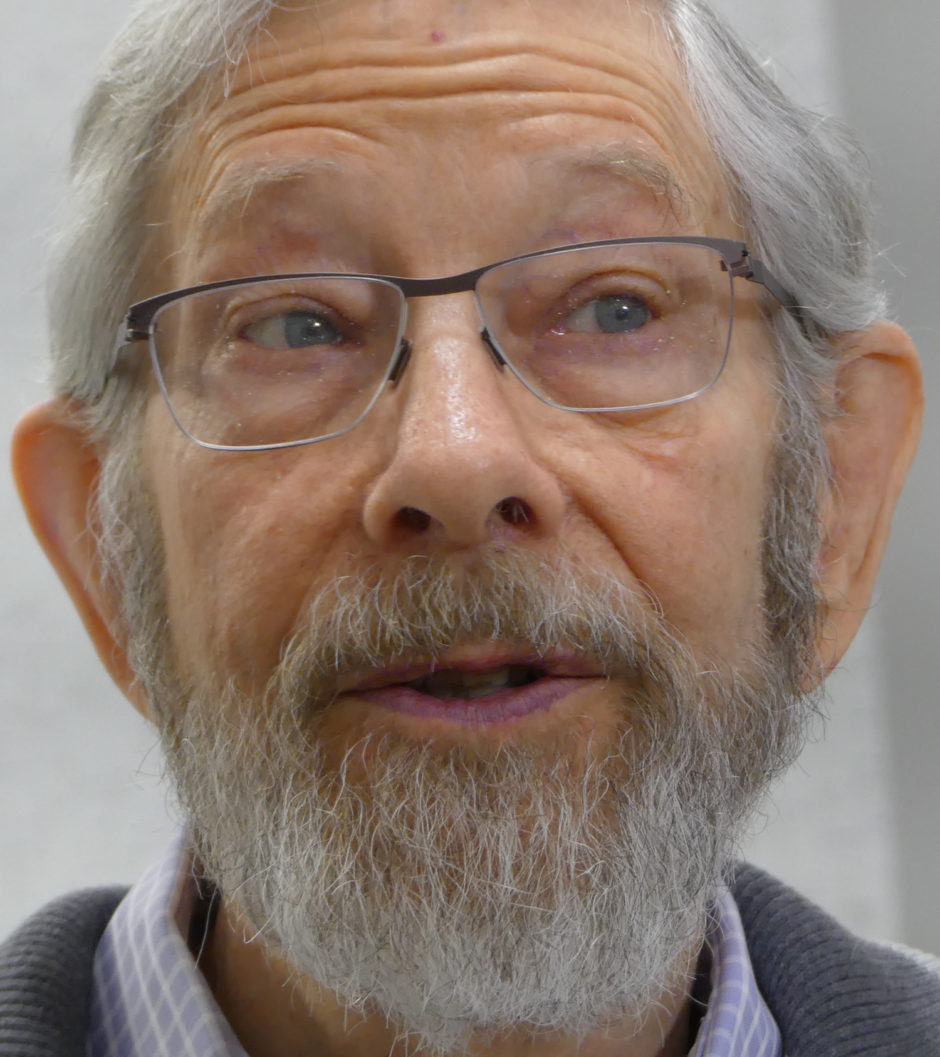

Dr. Dick Smith pauses to think about how many patients he has.

"Well I don't really know, because I told them all I was retiring and that they had to find other doctors," Smith says with a grin.

While Smith, 75, can't say how many patients he's had over his 52 years of practising, it's clear he's affected many lives.

Smith, who started practising in Manitoba in the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, is a gay doctor and activist who's had a huge impact on the health of gay men in this province.

"He's been my doctor for decades, decades, and I credit the man with saving my life. I truly do; no doubt in my mind," says John Lawrie, 66.

At the height of the AIDS epidemic, Lawrie remembers being pulled aside by the doctor and getting a stern warning to engage in safe sex only.

"Dr. Smith, I remember, took me by my hand and said, ‘John, we're going to have a talk about your sexual activity,' and basically told me, ‘No more doing what you want' and this and that. My sexual activity changed overnight like that."

Lawrie's twin brother died in December 1990 after getting AIDS. Many of his close friends died too.

"I think I would be dead" without Smith, Lawrie said. "They had no idea what caused it. They thought maybe sharing glasses. You wouldn't sit in a bar and share a glass with someone because maybe through saliva. We had no idea and we were scared, scared shitless actually."

Lawrie talks about the difference Smith made in gay men's lives:

'What he gave us in those days was hope,' John Lawrie says.

Smith made it his mission to stop the spread of HIV, learning more about what he was dealing with and doing outreach with men like Lawrie.

"People were scared. 'What is this? What's happening?' They thought maybe it's to do with poppers. They thought maybe it's to do with just having so much and so many STIs, maybe it was the antibiotics, maybe it was malnutrition and people not looking after themselves," Smith said.

Smith, a recent medical grad who had come from London England in 1972 to fill in for another physician in rural Manitoba, worked tirelessly to find out what was going on.

After first practising in Neepawa, Man., he started his own clinic in Winnipeg's Fort Rouge area in 1979, so he could have gay and lesbian patients.

His work also took him to San Francisco, where he went to a meeting with other doctors that he believes was the first gathering where clinical manifestations of HIV were reported.

In San Francisco, Smith also found himself part of the gay liberation movement.

It was an exciting and scary time to be alive.

"People were puzzled and they were apprehensive," he said.

At home in Winnipeg, Smith was kept busy as HIV continued to spread and eventually kill many of his patients.

"I didn't get to all the funerals."

Smith doesn't know how many of his patients died but estimates it could be somewhere around 100.

He was relentless in his efforts to educate gay men during a period before doctors had a test to screen blood. He made a pamphlet he's still proud of that focused on prevention and management and was part of an AIDS forum that made the news.

"And you know, it's interesting looking back at that. We had to ask the news cameramen to not come into the meeting, to not photograph people going into the meeting, because that would stop people going. They would just be too afraid to go."

Fear was so common Smith knew he couldn't just attend conferences and make pamphlets — he had to hit the bathhouse, where gay men went to socialize and hook up.

"We thought OK, we have to go to where the action is if we want to achieve what we need to do."

He and others started holding STI screening clinics in an upstairs room at O'Bee's Steam Bath but not many guys stopped by.

"I mean, they'd gone there for a purpose. They weren't really interested in nothing else," Smith said with a laugh.

"So eventually I said 'OK, well then I'll go down.' So I put on a towel and I went down there and I got quite a few dismissive laughs all right. I remember feeling quite upset about that, but anyhow, some people did come out and get tested and get educated."

The grey-haired doctor, who still has a slight British accent, is quick to mention others who helped him along the way, including a late nurse named Dennis Norbury. The nurse provided palliative care to Smith's patients in the privacy of their homes.

"At least I had the comfort of knowing that people who really did not want any publicity, they wanted their death to be shrouded in secrecy, that they could die at home with someone who would be there all the time with them, who was very expert in palliative care and would give them as comfortable a departure as they could possibly have."

Secrecy was the norm.

Smith's patients died at a time when relatives lied in obituaries about cause of death.

"The social stigma was phenomenal in those days. You have to live through it to understand," said Lawrie, who recalls his mother asking whether AIDS would be part of his brother's obituary.

"I said 'No brainer — of course, of course.' "

Jim Kane, 64, was Smith's patient after coming out in 1983. He tested positive for HIV right away but was one of the ones who survived the horror of the '80s and early '90s.

Smith encouraged Kane to break the secrecy and go public about living with HIV to end stigma. People needed to see a face and hear a name.

It's advice he's forever grateful for.

"It changed my life. It's given me a new purpose in life."

Kane doesn't want Smith's legacy and impact on Winnipeg's gay community to be forgotten.

"I think his service is commendable. You know, he broke down a lot of barriers," Kane said. "A true hero in our community."

Smith doesn't think he cried during the AIDS epidemic — he was too busy to stop and grieve — but today he tears up not about the deadly years but when reflecting on the people who supported him.

"One of the things that makes me feel most emotional is remembering at a time when no one knew how it was being spread that the female patients, the heterosexual patients in my practice, continued to have me deliver their babies. And it seems strange that that would be the thing I'm most emotional about, but I think it reflects acceptance at a time when it was so little," he said.

"I have to say that my patients in my practice were truly wonderful. There was only ever one patient, one elderly woman, who said to me ‘Oh Dr. Smith, why do you have to waste your time looking after those people?'"

That woman, a longtime patient who Smith still refers to as a "dear lady," decided not to come back to his practice.

"But there were others — amazingly, a Roman Catholic family that had a funeral in the cathedral and were totally open about it and that was, that was wonderful," he said, tearing up, his voice softening.

The funeral for their son sent a strong message within the church that the family would stand up for their kid and his friends despite the criticism they were sure to face, Smith said.

Smith went on to play a leading role in founding the Village Clinic on Corydon and then Nine Circles Community Health Centre, which he retired from when he was 65.

He continued to care for some male patients while retired and then came out of retirement to start the former Gay Men's Health Clinic, which was renamed Our Own Health Centre when it opened in a new space in the Exchange District in 2016.

A few weeks ago, Our Own Health Centre left that location to start operating out of Cardio 1 clinic at Confusion Corner.

Smith is not quite retired yet — a receptionist stops by during the interview to remind the doctor he has patients coming in just a few hours.

But he's serious about retiring this time. His life partner Doug Arrell, who has been by his side since 1977 not only as a lover but also a gay rights activist, isn't well.

Leaving his work behind won't be easy.

"The bitterness is the feeling that there'll be a lot of people I've seen a lot over the years that I may not see again and may not talk to again. And that is a loss, and I feel sad about that."

Smith has kept Our Own Health Centre running as the practice has struggled to sign on new doctors. Right now it has just one part-time physician and Smith, but about 3,000 patients.

Alan Turner, a volunteer board member for the health centre, says finding doctors has been a challenge.

"We've been actively looking for the last probably three years, since I got on the board, for any physicians," Turner said.

The non-profit thinks it's found a doctor to work full-time starting in May and Smith hopes he'll be able to stay on until then.

The clinic could hire four or five more full-time doctors just to manage the needs of male patients, Turner said, and the board would like to expand the operation even further.

"In a perfect world, we'd love to get a lesbian doctor or trans doctor or something like that, or somebody who is willing to look after that role, so we could be truly a clinic for the entire queer community."

This too is bittersweet for Smith.

"I feel a little nervous the project hasn't got really onto solid feet," he said.

However, there are a lot of good people with a lot of commitment involved in the project, he said.

Smith feels passionately that there is a benefit to having a gay doctor look after gay patients. He compares it to a female patient wanting to see a female gynecologist; it helps some patients feel comfortable and free to be candid with their doctor.

"I can really discuss people's sex lives with them using the language of our community and drawing on personal experience in a way that others might not be able to do."

Homophobia persists and people can gain strength from finding whipping boys, he said.

"The reality is that sexual and gender minorities will always be, always will be a minority and, like black people in certain communities or white people in certain other communities or the Jewish population, they are always potentially going to be scapegoats."

Lawrie said he hopes Smith will be honoured one day for his work.

"Dr. Smith gave us hope. You know, we're going to get through. He taught us to have pride in ourselves."

For Smith, his career was always about more than just medicine. Devoting time to social issues was key.

"How could you be a good gay doctor without being an activist?"