March 10, 2020

This story is part of Stopping Domestic Violence, a CBC News series looking at the crisis of intimate partner violence in Canada and what can be done to end it.

The small intimate partner violence (IPV) unit of the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary is used to playing the long game.

It takes years in some cases to build trust with women and men who have been abused, and encourage them to step forward and report it.

But when it happens, it's worth the wait.

"It's huge. It's heartwarming. I think it was only this week I popped you a text and said this victim is here!" Const. Lindsay Dillon said, turning to her partner Const. Nadia Churchill.

Dillon was assigned to the newly-formed domestic violence unit in 2014, as part of a pilot project. It was later renamed to focus strictly on intimate partner relationships.

Today, Dillon is joined by Churchill, a ten-year veteran of the force, and civilian crime analyst Malin Enström.

"I thought I was going to come in and save the world and help people, and that is very true, but not the way that I thought I was going to," Churchill said.

As a new police officer, Churchill found it frustrating to see people return to abusive homes time after time. She quickly learned her job wasn't exactly what she had expected.

"I have a much better understanding of the dynamics of those relationships and instead of asking, 'Why don't you leave?' I ask, 'Why do you stay?'" she said.

"And that list continues to grow every day that I speak to a victim."

It's difficult to detail what happens day-to-day in the IPV unit, because all three women admit it's not a job where you stop thinking about work when you get home.

When Dillon flicks on the radio in the morning and hears of an act of violence that happened overnight, her heart beats faster and her mind wanders.

"I'm like, oh God, I'm rushing into work to see if it's intimate partner-related."

The unit receives about 2,000 referrals a year. Those referrals can come from frontline police officers who suspect intimate partner violence, or outside organizations like women's shelters.

"So, I work with a lot of spreadsheets," laughs Malin Enström.

Enström reviews the overnight reports from patrol officers to detect any signs of intimate partner violence. Crimes which may not appear to be domestic-related on the surface could stand out for Enström, who tracks victims, offenders, addresses, crimes, and other details.

She also examines referrals from police officers who suspect inmate partner violence.

It's more than verbal and physical abuse.

"It can also be property damage, it could be a smashed phone, it could be harassing phone calls, it can be stalking," Enström said.

"It can be other types of property damage like damage to oil tanks or to houses and slashed tires."

One of the crimes that sets off alarm bells for Enström is sand being poured into a person's oil tank — a way to exert control over another person.

"It might not actually look like it's part of intimate partner violence, but because we know that address and the history of the individuals living there, we know that this is part of an escalation and intimate partner violence."

From there, Enström creates a risk assessment and passes the files on to Dillon and Churchill, who will begin to work the phones.

The job, she said, is to connect the dots and be proactive instead of reactive. To stop the escalation from harassment, to abuse, to homicide.

Not all about catching the bad guys

Statistics show family violence happens 25 to 35 times before police are even alerted, Dillon said.

And most times, it's not the victim who calls the police but a neighbour, family member or friend.

Very rarely are the calls a one-off.

"That's scary because by the time victims come to us, they've endured years of violence against them," Dillon said.

"At the end of the day, if a victim is not ready to come forward and disclose then we can't push that. And if that means not catching the bad guy then that means not catching the bad guy."

Dillon and Churchill said they have seen an increase in intimate partner violence. However, the unit sees that as a positive because they believe it's an increase in reporting — not violence itself.

"We haven't found Cortney's body yet and that is going to be an investigation I will take for the rest of my career. I told her we'd find her. And I won't stop until I find her." - Const. Lindsay Dillon

Through her data collection, Enström has noted a marked increase in the number of men who have come forward with stories of abuse.

"The majority of victims are still women. I don't have a specific stat but let's say nine out of 10 victims are definitely still women," she said.

"I would like to think that we have matured as a society and culture in terms of putting down, breaking down barriers for stigma and stereotypes of what a victim looks like."

The #MeToo movement, she believes, has helped grow momentum for men and women to report abuse.

The job, while rewarding, is also heavy. And, at times, devastating.

Lisa Lake's daughter Cortney went missing in June 2017 — the same day her ex-boyfriend was released from jail.

Her body has never been found and the RNC believe Philip Smith, who later took his own life, is the man responsible.

Dillon was there when police sat Lake down to say they believed her 24-year-old daughter, who was a mother herself, was dead.

Dillon was there when police told Lake that Smith had committed suicide and had not left a note revealing the location of Cortney's body.

In Lisa Lake's Mount Pearl home, Dillon's family Christmas card is displayed in the living room. She received a batch of cookies, too, she said.

"[Lindsay's] a godsend," Lisa Lake said.

"I've never seen a relationship like that before with an RNC officer and a member of the public."

Fighting tears, Dillon explains the bond she shares with Lake.

"I was very much involved in that file. Right from the start, Lisa and I were close and we're still close. We chat and text. It's difficult. It's heavy," she said.

"We haven't found Cortney's body yet and that is going to be an investigation I will take for the rest of my career. I told her we'd find her. And I won't stop until I find her."

Dillon, Churchill and Enström have grown into far more than just colleagues. They are each other's support. All working toward a common goal.

There have been a lot of sleepless nights and late night texts, Churchill said.

In short, they need each other.

"It's hard to get victims out of our minds when we try to build such a close relationship to them," she said.

"We've laughed together, we've cried together, we've traveled together, we need each other and if we didn't have the support of each other we'd probably be ... I don't know where."

What needs to change?

As part of CBC's series on intimate partner violence, multiple women have praised the IPV unit for helping them navigate a challenging, scary and often confusing system.

But they also believe the force needs to add additional officers to grow on its success.

Dillon and Churchill agree.

"We've been talking about it for years, to getting this unit to be a standalone unit where we have a supervisor, we have our analyst, and we have multiple investigators together," Dillon said.

"Not just the two of us so that we can take a team approach on some of these files and we can give these victims this consistency that we're looking for."

RNC Chief Joe Boland said he too would like to see the unit expanded, but said the funding and resources are not there yet. Adding an officer to the IPV unit would take one away from another.

Taking the step to charge an abuser is only the beginning, and often sets off a long court process which could see a woman being cross-examined on the stand and facing her ex-partner.

Churchill said it's important that the unit explain that to those who come forward, because the outcome in court is not always what one would imagine.

"It happens regularly, to the point where we hear from victims now who say I'm not even going to bother because they're just gonna get a slap on the wrist in court," Dillon said.

"And that's really unfortunate because it takes a lot for a victim to come forward and then it takes a lot in the investigation to go ahead with those charges and to meet what's needed to take that through the court system."

Churchill and Dillon said it's also disappointing for them when they see plea deals struck where charges are dropped, or a person they believe to be guilty is acquitted.

Sometimes, Dillon said, it doesn't appear as though the punishment fits the crime.

"What I might think is a sufficient punishment or sentence for somebody might not be what is able to be handed down to somebody."

But the unit is nothing if not patient. And if a person doesn't want to lay charges, that's OK.

"When you are ready to come forward, we are going to be here and we will we will hold your hand and we will help you through it as much as we can," Enström said.

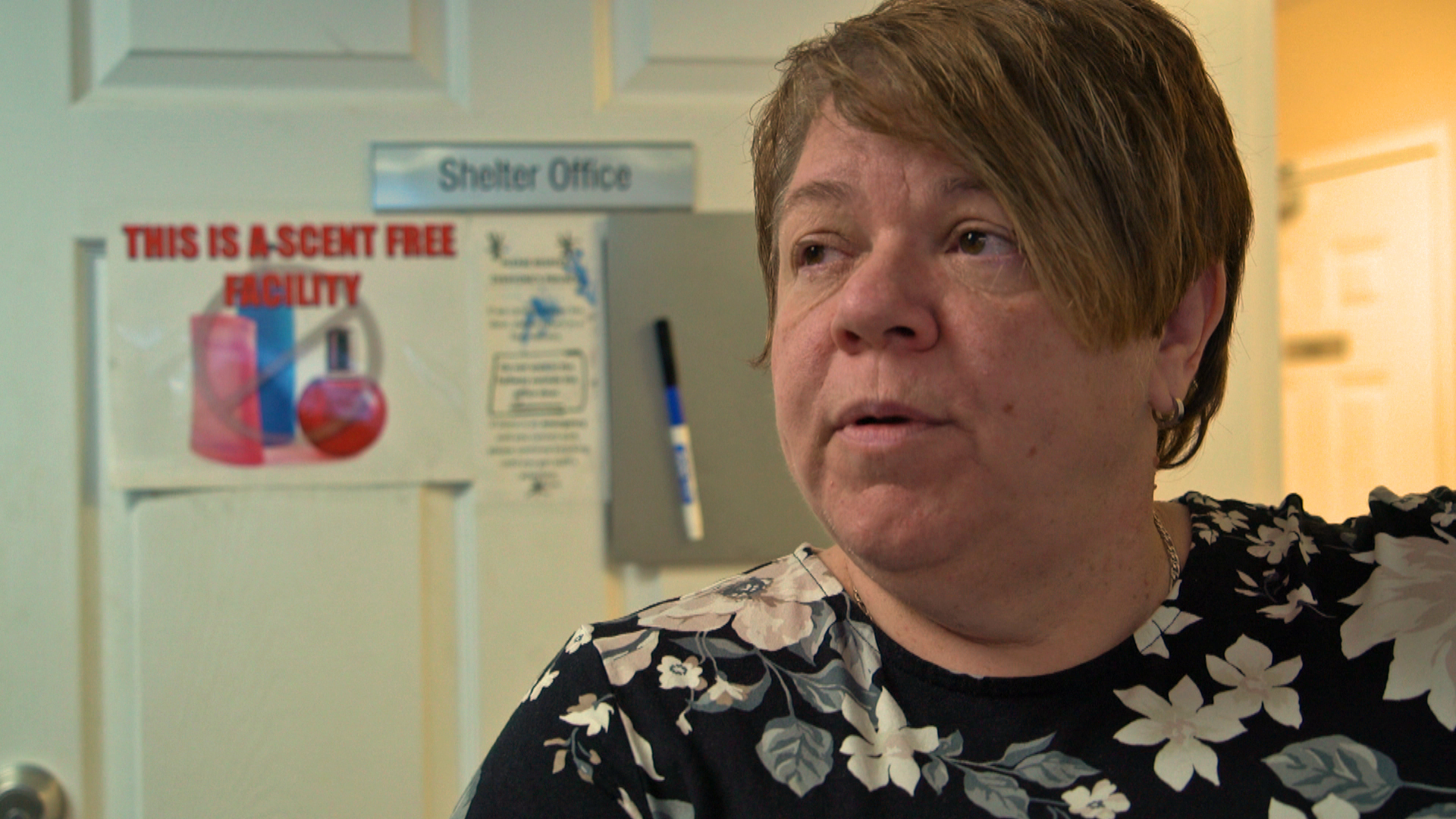

At Iris Kirby House in St. John's, executive director Michelle Greene hears the same concerns.

"It's just a colossal mess for some women," said Greene, who took on the job in 2017.

"There are so many barriers. Once you do [come forward], there's a challenge in having to tell your story so many times."

It's not just the criminal justice system which women have to navigate, Greene said. There could be involvement with housing, child protection, and more.

"I'm a social worker, many of the staff here have professional degrees as well, and we have trouble navigating many of the systems."

She has heard feedback from women who think there should be case managers for cases of intimate partner violence, to streamline the process from policing to court.

"We think it's sleepy little Newfoundland, we'll give you a cup of tea with Carnation milk and we'll put a quilt over ya and all is good. But in urban settings we're seeing all the situations you'd see in a major centre." - Michelle Greene

Iris Kirby House first opened in 1981, with a mission to provide shelter and a safe haven for women and children who are experiencing domestic violence.

In the three years Greene has been at the helm, the youngest resident has been two days old — an infant who escaped with her mother from an abusive home.

The oldest was an 86-year-old woman who was battered for years, and finally had enough.

"We're like firefighters," Greene said. "We don't know what's on the other side of the door but we need to be prepared."

The changing face of Iris Kirby House

Greene said Iris Kirby House takes nearly 15,000 calls a year.

Between shelters, homes and apartments on the northeast Avalon and Carbonear, there are 80 beds. Occupancy is almost always at 90 per cent.

The number of people seeking shelter is one challenge. Another is a more diverse clientele.

"We see a lot of women from different cultures," Greene said.

"Last September we had women here from five different countries, speaking five different languages. We had 13 women and 15 children speaking five different languages."

Being a non-diverse staff, Greene said they used Google Translate to get the women to communicate.

Greene said they've seen a spike in new Canadians, international students, women fleeing gang violence on the mainland, and women lured through dating websites into sex trafficking.

"It's often been, we think it's sleepy little Newfoundland, we'll give you a cup of tea with Carnation milk and we'll put a quilt over ya and all is good," Greene said.

"But in urban settings we're seeing all the situations you'd see in a major centre."

When Const. Shawna Park started as a police officer 15 years ago, she never thought part of her job would be reconnecting pets with their owners, shuffling them to veterinarians, and finding foster homes.

But it’s turned out to be one of the most rewarding parts of her job in the Royal Newfoundland Constabulary.

As a frontline officer, Park has heard the stories and responded to the calls: If I leave, he’ll kill my dog.

“They know that the minute they walk out that pet is going to be hurt or destroyed or killed or just even neglected,” said Park, at RNC headquarters in Corner Brook.

Park nearly single-handedly spearheads the RNC’s pet safekeeping program on the west coast, an initiative that’s meant to break down one of the reasons why people in abusive relationships won’t leave.

Statistics used by the RNC show that 59 per cent of people in violent relationships who have family pets refuse to leave them behind.

And that is often for good reason — 85 per cent of the time, threats of violence toward a person’s pet are carried out.

“I've heard stories over the years where people have been in the situation and they've had no choice but to leave the pet behind and within a week of leaving their children's puppies are put down,” Park said.

“I’ve heard stories where the animals would be beaten and abused themselves.”

An animal is often a well-loved part of the family, and becomes a bargaining chip in a relationship.

“As an animal lover myself, I know that if something happened to one of my pets I'd be absolutely devastated,” Park said.

Tears all around

In 2014, Park joined a working group to develop strategies to combat intimate partner violence. The pet safekeeping program was borne from those discussions.

As Park was on the only officer in Corner Brook on the group, it was her task to carry it out.

"I thought, 'Wow, how am I going to do this?'" Park laughed.

She partnered with the NL West SPCA, the Humber Valley Veterinarian's Office and Willow House, a women's shelter. Another officer has also now stepped up to help out.

Despite the extra work, the reward is worth it.

"I brought that pet directly to her. I didn't think a dog could cry but this dog cried. And this lady started to cry and before I know it, the tears are rolling down my cheeks," Park said.

"She said, 'If it wasn't for this program I would still be in that situation and someone would be hurting me every day. You looked after my baby,' and for her, that was her baby. That's all she had in this world that was positive and good."

If you need help and are in immediate danger, call 911. To find assistance in your area click here.

For general advice, contact IPVU at IPV@rnc.gov.nl.ca or call 709-729-8093